Platinum is a poor substitute for palladium

2021.08.20

Discovered by English chemist William Wollaston in 1803, palladium was named after the asteroid ‘Pallas’. The silvery-white metal is one of six platinum group elements (PGEs) found in the Periodic Table of the Elements. The others are iridium, osmium, platinum, rhodium and ruthenium.

Of all the PGEs, palladium is the least dense and has the lowest melting point.

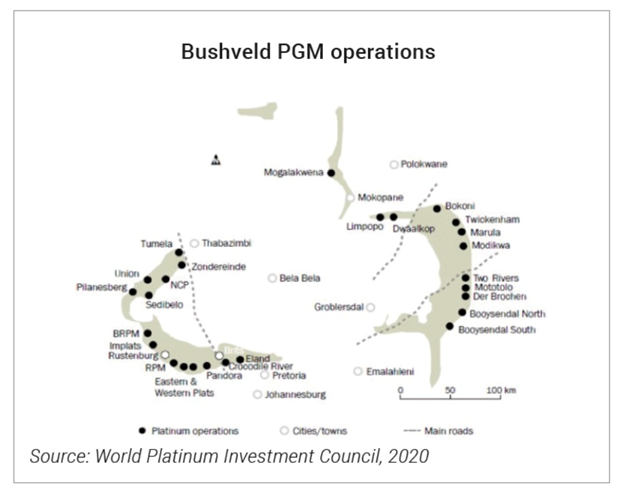

Palladium is an uncommon element in the Earth’s crust. Deposits of palladium and other PGEs are rare, with the largest occurring in South Africa’s Bushveld Igneous Complex covering the Transvaal Basin, the Stillwater Complex in Montana, the Sudbury Basin and Thunder Bay District of Canada, and the Norilsk Complex in Siberia. Recycled catalytic converters are also a source of palladium supply.

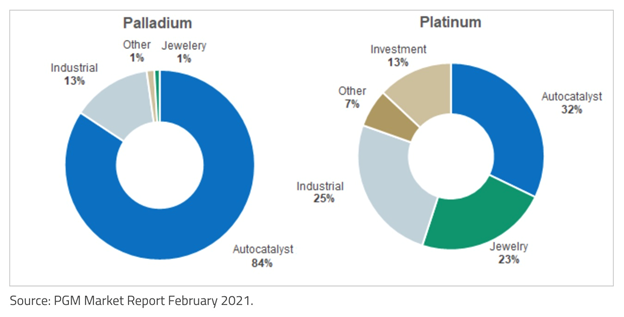

About three-quarters of palladium demand comes from catalytic converters. Also known as autocatalysts, these devices reduce noxious emissions, and have been an important reason for internal combustion engines (ICEs) polluting up to 90% less than they did in the 1970s, along with the tightening of US tailpipe emissions regulations, led by California.

Catalytic converters are supplied for diesel-fueled and gasoline engines. Both contain a mix of PGEs and other metals including platinum and palladium. A higher percentage of platinum is used in diesel autocatalysts, whereas gasoline autocatalysts have more palladium.

The lustrous metal is also used in electronics, surgical instruments, jewelry, watch making, aircraft spark plugs, hydrogen purification and groundwater treatment.

As the world transitions from fossil-fueled “ICEs” to battery-powered electric vehicles, the internal combustion engine is unlikely to be resigned to the scrap heap, just yet. Gasoline vehicles and gas-electric hybrids will gradually displace more-polluting diesels, the former equipped with catalytic converters to filter out pollutants like NoX and particulate matter.

This means growing demand for materials that go into gas-powered autocatalysts, including palladium.

The platinum group metal is set for a supply squeeze for the 10th straight year. Driving palladium demand are higher sales of gasoline vs diesel units and tighter pollution controls.

Palladium use in hybrid vehicles, seen as a bridge between gas-powered cars and pure electrics, is a growing source of demand.

(In Europe, second-quarter registrations of hybrid vehicles jumped by 240%, compared to Q2 2020, while plug-in hybrid registrations more than tripled. Diesel’s share of the European market slipped from 28% in last year’s quarter, to 18.4% in Q2 2021, according to S&P Global).

Supply, meanwhile, has been disrupted by the covid-19 pandemic and flooding at Arctic mines. According to a recent analysis by Sprott, A primary driver of higher palladium prices remains the structural deficit in which demand continues to greatly exceed combined primary and secondary supplies, despite record recoveries of palladium from automotive scrap and sharply higher output in South Africa.

On May 4 palladium hit a new record high of $2,890/oz. Despite a recent pullback, over the past year Pd is up 14%. Palladium has mainly traded above gold since 2019.

‘Diesel-gate’

The “diesel-gate” scandal at Volkswagen put tailpipe emissions on the radar of policy makers especially given that the rigging of diesel cars to fraudulently meet emissions came amid reports of the dangers of air pollution to human health.

Such concerns led the EU to set a target of cutting emissions by at least 40% by 2030, from 1990 levels.

China, whose major cities are often cloaked in a thick fog of air pollution, has also implemented tougher vehicle emissions standards. The country is targeting a reduction of between 26 and 28% of emissions from 2005 levels by 2030. The new rules demand that vehicles emit fewer pollutants such as nitrogen oxides, particulate matter and ammonia.

The greater loadings of palladium per vehicle versus other metals, due to tighter emissions regulations in the EU and China, are helping to keep a solid floor under palladium prices. A diesel engine requires 5 to 10 grams of PGEs, with the majority being platinum. A gasoline engine uses 2 to 7 grams of PGEs, relying more on palladium.

Palladium vs platinum

According to Sprott, Palladium demand is highly concentrated in automotive uses, with about 84% of yearly demand coming from auto production. While palladium’s “sister metal” platinum is used in a range of industrial applications and has investment demand and jewelry production, palladium use is far more focused on the auto sector and autocatalysts.

The platinum market is currently suffering from demand destruction, with prices trailing both gold and palladium. Earlier this month Pt slumped to a seven-month low, as the spread of the Delta variant hurt the outlook for industrial commodities, particularly in top commodities consumer China.

Platinum, which also serves as a monetary metal, has also been sideswiped by rumors that the US Federal Reserve could begin tapering its $180 billion per month stimulus program. A third factor behind trailing prices is the global chip shortage, which has curbed auto production. Since this year’s peak in February, platinum has tumbled more than 20%.

Production challenges

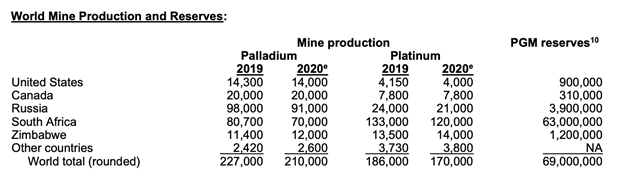

Palladium is extracted as a by-product of nickel mining in Russia, and platinum mining in South Africa. These two countries control three-quarters of global production.

However, platinum mining in South Africa is frequently interrupted by labour unrest. In 2014 workers at the country’s three major producers — Lonmin, Anglo American Platinum and Impala Platinum — downed tools for five months demanding that wages be doubled. The strike was the longest and most expensive in South African history, shutting down about 40% of the world’s platinum production.

The country’s platinum miners are under constant pressure to contain costs, because their mines are some of the deepest and most labor-intensive in the world. High temperatures are also a serious issue. Platinum is being mined in reefs up to two kilometers deep, where virgin rock temperatures have been measured at 70 degrees C; 75 degrees is considered to be the limit for mining.

There are significant infrastructure constraints, too. The country has limited processing capacity and water is a constant concern. In 2018 Cape Town came dangerously close to running out of water and was only saved from “Day Zero” by stringent water restrictions.

Power in South Africa is notoriously unreliable — blackouts are frequent. In 2008 the country’s electricity grid nearly collapsed due to a shortage of coal for power stations and system faults. Eskom, the main utility, ordered all mining operations to evacuate underground staff and to stop mining for five days, then cut electricity supply across South Africa to minimum levels; the mining industry uses about 15% of Eskom’s output. The stoppage, affecting roughly a quarter of generating capacity, cost the industry billions in lost production.

With palladium prices at record highs, it makes sense for platinum and nickel companies to ramp up production to take advantage. Problem is, there is limited scope for producers to increase supply, especially in South Africa. Just as important, a boost in output could add to the glut in platinum, which is these miners’ bread and butter.

To the first point, despite high palladium and rhodium prices extending the life of mine shafts in the Rustenburg platinum belt, producers are not keen to invest in new mines.

Impala Platinum, a major industry player, expects output from South Africa’s mines to decline over the next few years. New projects in South Africa would take years to develop, while those in neighboring Zimbabwe may be stymied by political and economic uncertainty, according to a company spokesman, Bloomberg reported.

The second point, about flooding the platinum market, thereby depressing prices further, is due to the fact that for every ounce of palladium mined, 2-3 oz of platinum comes with it. The dilemma South African miners face is one of robbing Peter to pay Paul — in this case, extracting cheap platinum ounces in order to be paid more for palladium and rhodium, currently priced at USD$17,831/oz.

No substitutes

Some have suggested that platinum could be substituted for palladium if palladium continues to trade significantly higher than platinum.

A recent Bloomberg article posits that the rally in palladium that has seen it more than triple in value since 2018, is nearing its end as demand headwinds build.

The piece notes that BASF, the German conglomerate, has come up with new autocatalyst technology that allows for partial substitution of palladium with platinum.

“We see the beginnings of platinum being substituted back into gasoline catalytic converters,” Bloomberg quoted David Jollie, head of sales and market insight at global miner Anglo American Plc. “This will bring palladium back from its fundamental supply deficit and closer to balance.”

Another headwind for palladium is the increasing popularity of electric vehicles. With EVs expected to account for a third of global auto sales by 2030, compared to just 4.3% in 2020, according to BloombergNEF, the need for autocatalysts would gradually decline along with palladium demand.

At AOTH, we are not so sure.

For one thing, car makers have for the most part switched over to palladium-heavy autocatalysts. They did so in the 2000s because palladium was much cheaper than platinum.

Re-tooling them back to platinum would be unproductive and expensive — likely negating the money saved by purchasing cheaper platinum.

It took several years for car-makers to switch from platinum to palladium, so reversing the process would also take time. Moreover, over the past 20 years, autocatalyst technology has advanced, so it wouldn’t just be a case of reviving old designs.

Geoffrey Caveney, a contributor to Seeking Alpha, explains the hesitancy of automakers to go back to platinum-dominant autocatalysts, despite a significant price discount.

The reason he argues, is due to a greater diversity of countries that mine palladium, versus those that produce platinum. The latter market is almost completely dominated by South Africa, whereas some palladium, albeit in relatively small quantities, is mined in Canada, the US, Zimbabwe and a handful of other countries.

Caveney writes:

Looking at the production gap another way, the U.S. produces more than three times as much palladium as it does platinum, and Canada and other countries produce almost twice as much palladium as they do platinum.

Therefore, in case of a significant temporary or prolonged supply disruption from South Africa in particular, or from Russia and Zimbabwe as well, automakers and other manufacturers in North America and the rest of the world could potentially have much more difficulty dealing with supply shortages in platinum, than they would with palladium.

In other words, the threat of a supply disruption just isn’t worth the risk.

In 2014 the five-month-long platinum mining strike caused Ford and Toyota to temporarily suspend operations at its South African car plants.

The current micro-chip shortage which has significantly impacted the auto industry, is a more recent reminder of how reliance on a handful of semiconductor manufacturers can come back and bite you. The industry is currently dominated by just three companies — TSMC of Taiwan, Samsung of South Korea and US company Intel.

It has also been said that palladium-heavy catalytic converters perform better than platinum under extreme-conditions emission tests. According to Johnson Matthey Plc, which makes the devices, technological advances are needed before platinum can match the performance of existing palladium-based autocatalysts.

Finally, the above-mentioned Sprott report says that the volume of palladium currently going into autos is so much higher than platinum, that there would be a marginal impact from platinum substitution:

Annually, about ~9.5 million ounces (Moz) of palladium are used in autos, compared to ~2.9 Moz of platinum.

With palladium prices shooting higher and sourcing struggles ongoing, automakers are slowly shifting back to platinum. Analysts are projecting about 1.5 Moz of current annual palladium usage will revert to platinum by 2025. Still, that’s a slow process and a marginal amount compared to the total volume of palladium (which still faces higher future loadings to meet clean-air emissions targets).

Palladium One Mining

Tight market conditions for palladium will remain so for the foreseeable future in the absence of new palladium deposits, and as long as gasoline-powered vehicles keep rolling off assembly lines.

Considering the difficulty the world’s palladium miners, especially those in South Africa, are having increasing production, the onus is on smaller companies to find and develop new deposits.

Palladium One’s (TSXV:PDM, OTC:NKORF, FSE:7N11) LK (Läntinen Koillissmaa) copper-nickel-PGE project in Finland is one of very few palladium-dominant plays, meaning it stands to benefit greatly from continued palladium price strength.

The company is making great progress at two targets, Kaukua South and Haukiaho, the latter where a maiden resource is expected by the end of the third quarter.

In early July PDM announced that two Induced Polarization (IP) surveys expanded the 4-km-long Kaukua South IP anomaly to a strike length of more than 7 km. According to the news release,

Drilling to date has confirmed extensive mineralization over the initial 4-kilometer Kaukua South anomaly; the 3-kilometer expansion suggests a much large resource endowment is possible.

With a treasury of $15 million, Palladium One is well funded to carry out planned exploration activities at its LK PGE-copper-nickel project in Finland and its Tyko copper-nickel project in Ontario. An Aug. 17 corporate update shows there is plenty of news left to come from PDM before the end of the year, generated from: resource definition drilling at Kaukua and Kaukua South; a maiden resource estimate at the Haukiaho zone and an updated resource at the Kaukua areas; metallurgical testing; and a preliminary economic assessment (PEA) planned for mid-2022.

Palladium One Mining

TSXV:PDM, OTC:NKORF, FSE:7N11

Cdn$0.21 2021.08.18

Shares Outstanding 248m

Market cap Cdn$50m

PDM website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security. Richard does not own shares of Palladium One Mining (TSXV:PDM). PDM is a paid advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.