Norden Crown searching for high-grade VMS deposits in Sweden’s historic mining district

2022.01.31

In mining, the term “mineralization” is typically referred to as the deposition of economically important metals in the formation of orebodies, or “lodes”, by various processes.

As such, the success of a project is often intertwined with the geology and type of mineralization on which it sits, as they dictate what mineral commodities can be extracted from the ore; the best ore deposits are those that contain large amounts of minerals.

While ore deposits are highly variable in nature and origin, the most important kinds can be grouped into three main categories: magmatic, hydrothermal, or sedimentary.

Magmatic Ore Deposits

Magmatic ore deposits are essentially masses of igneous rocks containing sufficient abundance of minerals such that mining is profitable.

These can be subdivided into: 1) magmatic sulfides, which account for much of the world’s known natural resources of nickel and the platinum group elements; 2) pegmatites, which are formed during the final stage of magma crystallization and contain mostly quartz, feldspar and mica, with the rare occasion of encountering valuable commodities like lithium, boron and rare earth elements; and 3) kimberlites, which are mined exclusively for diamonds.

Hydrothermal Ore Deposits

Hydrothermal ore deposits are accumulations of valuable minerals formed from hot waters circulating in Earth’s crust through fractures. They eventually create metallic-rich fluids concentrated in a selected volume of rock, which become supersaturated and then precipitate ore minerals. These deposits fall into five main categories: porphyry, skarn, volcanogenic massive sulfide, sedimentary exhalative, and epigenetic.

Porphyry deposits are a special kind of hydrothermal deposit. They are formed when hydrothermal fluids, derived from magmas at depth, carry metals toward the surface and deposit minerals to create disseminated ore deposits. These deposits are important sources of copper, molybdenum, and gold.

Skarns are one of the more abundant ore types in the Earth’s crust and form in rocks of almost all ages, mostly limestone or dolostone. Common skarn minerals include calcite and dolomite, and many Ca-, Mg-, and Ca-Mg-silicates. Some skarns, however, are valuable mineral deposits containing copper, tungsten, iron, tin, molybdenum, zinc, lead, and gold.

Volcanogenic massive sulfides (VMS) are created by volcanic-associated hydrothermal events in submarine environments. They are predominantly stratiform accumulations of sulfide minerals that precipitate from hydrothermal fluids on or below the seafloor. These deposits are one of the richest sources of zinc, copper, and lead, with gold and silver as byproducts (more on VMS deposits later).

Sedimentary exhalative (SEDEX) deposits are geologically close cousins to VMS deposits, with the main difference being their host rocks. While SEDEX deposits are considered the most important source of zinc and lead, and have produced significant silver and sometimes copper, they are not as commonly found compared with other deposit types, and most of them are not economical to mine.

Epigenetic deposits refer to those not directly associated with a pluton as they are formed much later than the rocks which enclose it. These deposits are especially concentrated in a curved zone called the Viburnum Trend in southeast Missouri. As a result, many epigenetics are also known as Mississippi Valley type (MVT) deposits.

Sedimentary Ore Deposits

Sedimentary ore deposits are formed in one of two generalized geological processes: either as a result of mineral precipitation from solution in surface waters, or as a result of physical accumulation of ore minerals during processes of sediment entrainment, transport and deposition.

Sedimentary ore deposits can be further subdivided into placers (alluvial sand), banded iron formations, evaporites, laterites, and phosphorites. The principal metal ores found in these deposits are sulfides of zinc, lead, copper, and iron, and oxides of iron and manganese; in particular, they yield a large proportion of the world’s lead and zinc output.

VMS — Key Source of Future Metal Supply

While each category and subcategory of ore deposits on Earth provides us with valuable mineral resources that helped build the foundation of our society, one type of deposit that stands out in particular is volcanogenic massive sulfides (VMS).

VMS deposits are the primary source for many of the materials used to mold the modern world. These include zinc, lead, and copper, all of which are set to see increased demand amid the global transition to clean energy in the coming years.

Copper, for instance, is projected to reach a total demand of 40Mt in 20 years, which is twice the current mine supply of about 20Mt, according to BloombergNEF.

Therefore, the mining industry would need to invest heavily in new discoveries to fulfill the widening supply gap, and the type of mineral deposits that have been significant producers are the best bets.

VMS deposits have proven to be a major source of the world’s zinc and copper, accounting for 22% and 6%, respectively, of global production. They are also important producers of silver, gold, and lead, representing 8.7%, 2.2%, and 9.7% respectively.

To date, more than 900 VMS deposits have been discovered across the globe, with average production of roughly 17Mt grading 1.7% copper, 3.1% zinc, and 0.7% lead. These include a few giant mineral deposits (greater than 30Mt) and several copper-rich and zinc-rich deposits of median tonnage (~2Mt).

Volcanogenic massive sulfides, as the name suggests, are associated with ancient underwater volcanic activity dating back to more than 3 billion years, and still continuing to this day.

VMS deposits are usually formed during periods of rifting, when the earth’s crust is stretched thin due to the pushing and pulling of tectonic plates as they move towards and away from each other. As the crust warms, the ground softens, allowing hot magma to move up towards the ocean floor.

The magma either pushes through the earth’s surface, thus forming a volcano, or causes cracks that draw in seawater. The water is superheated and imbued with minerals, then expelled to the surface through black and white smokers. These plumes of minerals flowing from cracks in the ocean floor eventually settle back to the ocean the further they move away from the heat source.

The continual activity of the smokers and the deposition of minerals on the seafloor eventually form mineralized beds – the black and white smokers of today will become the VMS deposits of tomorrow. Through plate movements, ancient mineral-rich beds are transposed onto land that was once underwater.

Due to the formation of clusters of deposits or ore lenses in close proximity, and the polymetallic nature of the ore, VMS deposits have immense potential for long-term production.

Typically, several deposits feed a central mill, creating economies of scale. The byproduct credits generated from production of different metals can also help mining companies enhance their cash profile.

VMS deposits have long been recognized, by both majors and juniors, as potential “elephant” country. And, because of their polymetallic content, they continue to be one of the most desirable because of the security offered against fluctuating prices of different metals.

Several major VMS camps are currently known in Canada, such as Flin Flon – Snow Lake, Bathurst and Noranda. These high-grade deposits are often in the range of 5 to 20Mt, but can be considerably larger. Some of the largest VMS deposits in Canada include the Flin Flon mine (62Mt), the Kidd Creek mine (+100Mt) and the Bathurst No. 12 mine (+100Mt).

VMS Hunting in Sweden

As VMS deposits are found almost everywhere on Earth, there exists potential for new VMS camps like those in Canada to emerge in places that have been mostly overlooked by the mining industry.

One region with such potential is Scandinavia, led by Sweden, whose mining history dates as far back as 6,000 years from today. The Skellefte district in northern Sweden, for example, has a rich endowment of volcanogenic massive sulfides.

Sweden’s first mine, the Falun copper mine in Dalarna county, was a giant VMS deposit that produced as much as two-thirds of Europe’s copper for hundreds of years.

Archeological and geological records show that Falun first started being mined around 1,000AD. In its golden era, Falun produced as much as 3,000 tonnes of copper, helping Sweden to fund many of its wars in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The mine remained in operation until 1992; it later became a museum and World Heritage site.

Sweden is also a large producer of iron ore. Kiruna, located in Lapland province, is the world’s largest underground iron ore mine.

Every day, Sweden-owned LKAB pulls 750,000 tonnes of iron ore from hundreds of meters below surface – the equivalent volume of a 12-storey building.

Kiruna made headlines several years ago for a 20-year plan to move the town of Kiruna to a new location, after it was discovered that cracks from mining were appearing in populated areas. Instead of closing the mine, the 20,000 residents and the town’s main buildings are being relocated, allowing the 4,000 townspeople who work there to keep their jobs.

Sweden is Europe’s second-biggest gold producer after Finland. Gold was found at Boliden in 1924, from which the Swedish multinational mining company Boliden AB took its name. Once Europe’s largest and richest gold mine, Boliden closed in 1967. The Boliden Group currently produces nearly 18,000 kilograms of gold a year and has three gold mines plus two gold smelters.

Sweden’s mining success clearly stems from its rich geological endowment; it lies overtop of the Baltic Shield, which spreads throughout Sweden, the Fennoscandian Peninsula and parts of Russia.

In total, the country has about 15 metal mines in operation. Between Sweden and Finland, there are 30 mines and six smelters. Aitkik in northern Sweden is Europe’s largest copper mine. Aitkik was established in 1968 with approximately 39 million tonnes of ore processed into copper, gold and silver concentrates in 2017.

In southern Sweden, Boliden’s Garpenberg mine is the oldest mining area in Sweden still in operation, with a 120-million-tonne VMS deposit. The Zinkgruvan underground mine is Lundin Mining’s flagship operation in Scandinavia, producing zinc, lead and copper concentrates.

For mining companies and explorers, Sweden is an extremely desirable country to work in. It has nearly 100 companies with active exploration permits, and around 6,000 people directly employed in the industry. A 2011 national strategy for mineral exploration has resulted in more funding for mapping and gathering data on minerals.

Political stability, a solid legal system based on penal and civil law, and highly developed infrastructure are important pluses for mining. Sweden has 12,000 kilometers of rail track (85% electrified) and 69 ports including Goteborg, Falkenbergs Terminal, Ahus and Stockholm.

Another little-known fact about Sweden is the low cost of power. Commercial electricity contracts are in the order of 4 to 5 cents a kilowatt-hour, which is 20% cheaper than the normal cost of power in Europe. That’s important for mining because it allows miners to lower their cut-off grades in order to process more ore economically.

The corporate tax rate is a competitive 22.5% versus the mid-20-percent range in neighboring Norway. In comparison, the corporate tax rate in Canada is 26%.

Norden Crown Metals

Leading the next line of Scandinavia-focused explorers is Norden Crown Metals Corp. (TSXV: NOCR) (OTC: NOCRF) (Frankfurt: 03E), which is searching for high-grade base and precious metals deposits in this prolific part of the European continent.

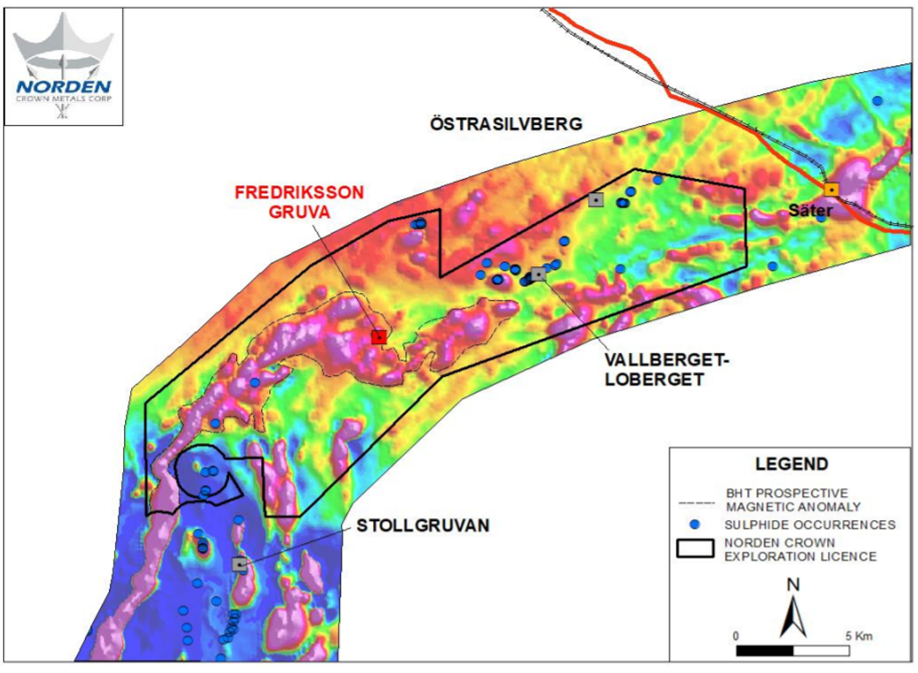

One project that Norden has been actively advancing is the Gumsberg property in southern Sweden. This 18,300-hectare land package, consisting of five exploration licences, is known to host multiple zones of VMS-style mineralization.

The project is strategically located in the Bergslagen mining district, between the past-producing Falun and Saxberget mines, and the active Garpenberg (Boliden) and Zinkgruvan (Lundin) mines (see map below).

The VMS deposits at Gumsberg were mined from the 13th century through the early 1900s, with over 30 historic mines present on the property, most notably the Östrasilverberg mine, which was the largest silver mine in Europe between 1300 and 1590.

Despite its long-lived production history, relatively little modern exploration has taken place on the Gumsberg property.

Nine holes (728m) were drilled in 1939 to test the depth extent of several prospects with outcropping VMS and related surface mineralization. An additional 12 holes were drilled during the Second World War and in 1958.

In 2016, through a combination of mapping, sampling, geophysical surveys and compilation of historic drill data, Norden and partner Eurasian Minerals were able to generate multiple high-priority drill targets near historic workings.

A reconnaissance diamond drilling campaign targeted exhalative-type lead-zinc-silver mineralization and replacement-style zinc-lead mineralization. Four holes drilled along the +2km long Vallberget-Loberget trend of historic mines (one of the key mineralized trends on the Gumsberg property) intersected significant intervals of mineralization.

Results included 2.8m of 17.9% Zn, 6.9% Pb, 0.5% Cu, and 68.9 g/t Ag at a depth of 32m below surface, and 3.0m of 9.2% Zn, 3.0% Pb, and 12.8 g/t Ag at a depth of 22m below surface. Both drill intercepts cut exhalative-style VMS mineralization, with true widths estimated to be 80-90% of the reported intervals. Replacement-style mineralization was intersected by one drill hole with an interval of 5.7m of 6.5% Zn.

These drill results demonstrated that multiple horizons of exhalative VMS-style mineralization are indeed present in the stratigraphy and contain interbedded zones of replacement-style mineralization. The Gumsberg project is now estimated to contain approximately 27km of stratigraphy prospective for VMS containing base and precious metal mineralization.

Norden’s work at Gumsberg has focused on advancement of the multiple mineralized trends on the property.

Last year, the company also began drilling on the Fredriksson Gruva target, a past-producing zinc-lead-silver mine, as part of an 11-hole, 2,365m diamond drill program on the Gumsberg property.

The idea behind 2021 drilling was to demonstrate that the mineralization at Fredriksson Gruva continues below the old mine workings, which extend to 91m depth, and to confirm historical silver-zinc-lead grades, thicknesses, and continuity.

The drilling at Fredriksson Gruva led to what Norden calls an “exceptional discovery”, demonstrated by significant results from the first three holes, which intersected significant mineralized widths ranging from 8.15-13.60m of precious and base metal, massive and semi-massive sulfide mineralization.

prospective magnetic anomaly

More importantly, this discovery was made within a geological setting unique to mineralization belonging to the Broken Hill Type (BHT) clan of silver rich zinc-lead ore deposits.

Broken Hill Types are some of the largest and highest-grade ore deposits in the world. They are distinguished from other silver-zinc-lead deposits by the chemistry of the sediment that hosts them, and they are usually associated spatially and temporally with volcanism.

BHT deposits have been discovered in Australia — the Broken Hill mining property in New South Wales, a large silver-lead-zinc deposit from which BHT Billiton takes its name — South Africa, and parts of the Bergslagen mining district of southern Sweden, which is where Gumsberg is located.

Conclusion

“Massive sulfide deposits are special because it is possible to delineate large tonnages from comparatively small drill footprints due to the high density of the mineralization,” said Norden’s chairman and CEO Patricio Varas last year when talking about the Gumsberg project’s growth potential after confirming the BHT-style mineralizing system at Fredriksson Gruva.

Just how significant were the drill results at Fredriksson Gruva? To put into perspective, the GUM-20-09 intercept (10.35m of 5.24% Zn, 1.84% Pb, and 43.86 g/t Ag) is comparable in width to the height of a three-storey building.

Additionally, Norden continued to cut high grades at the Östrasilvberg prospect from last year’s drilling; several holes intersected variable widths of massive sulfides with significant high-grade precious and base metal mineralization, including 2.6m of 476.27 g/t AgEq at a depth of 238.4m.

Norden is now in the enviable position of having three individual prospects on the Gumbsberg property — Östrasilvberg, Fredriksson and Vallberget-Loberget — that host massive, high-grade mineralization to chase and are, imo, each capable of returning an economic mineral deposit.

Norden Crown Metals

TSXV: NOCR, OTC: BORMF, Frankfurt: 03E

Cdn$0.11 2022.01.25

Shares Outstanding 53m

Market cap Cdn$5.8m

NOCR website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Richard owns shares of Norden Crown Metals (TSXV: NOCR). NOCR is a paid advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.