MXR seeking sedimentary copper in Colombia

2019.11.02

West of Glen Canyon, Utah, a 90-million-year-old secret is hidden beneath the dry, desolate landscape. What is now one of the largest sand-dune deserts in the world, was once the middle of a vast inland ocean. Plying the waters of the Western Inland Seaway, a human transported back in time would have seen dozens of shark species, many now extinct, turtles the size of cars, marine mammals, and a beach so full of oysters, it would have been impossible to find a patch to stand on.

Oysters live in shallow, salt-water environments, so this ancient beach would have been the perfect environment for them to proliferate. Today it’s possible to pluck a 90-million-year-old oyster from the desert floor, though not easy, because they are so tightly packed together, encased in stone.

This region, the Tropic Shale, composed of mostly mudstone and claystone, averaged between 183 and 274 meters thick. Observing it now, one can see patches of deep gray, indicative of carbon and little oxygen. In fact, this ancient sea had an anoxic environment that limited the growth of small life-forms that would normally consume the bones of dead animals, making the Tropic Shale an ideal environment for preserving marine life.

Scientists have also seen evidence of an ocean in the most un-likeliest of places: the Andes. In 2007 an expedition from the American Museum of Natural History brought back an assemblage of marine fossils, including whales, from a prehistoric seabed in southern Chile that was over 1,500 meters elevation.

After the animals died, up to 20 million years ago, their carcasses settled to the ocean floor and were embedded in sediments. Then, when tectonic plates smashed together and formed the Andes, the sediments and their fossils were carried to the tops of mountains.

These large expanses of inland seas, teeming with long-extinct fish, mammals and reptiles, are intriguing to ponder for another reason; they are the source of some of the world’s largest accumulations of copper, brought together through a confluence of geological factors that gave rise to sedimentary copper deposits.

Sedimentary copper deposits

Sedimentary copper deposits are formed in ocean basins, where the seabed is composed of porous materials such as sandstone, limestone and black shale, through which copper and other minerals travel up and become trapped in the rock layers.

The process of mineral deposition is quite different from a copper porphyry deposit, which is formed when a block of molten-rock magma cools. The cooling leads to a separation of dissolved metals into distinct zones, resulting in rich deposits of copper, molybdenum, gold, tin, zinc and lead. A porphyry is defined as a large mass of mineralized igneous rock, consisting of large-grained crystals such as quartz and feldspar, that is often suitable for bulk mining.

Copper porphyries can be visualized as a bag of flour with millions of grains of rice, where the grains are tiny pieces of copper and other minerals, spread throughout a large area, whereas sedimentary copper deposits are like a stack of books. Sedimentaries may also be tabular in form, though frequently folded and faulted.

Among the largest copper porphyry deposits are Chuquicamata (690 million tonnes grading 2.58% Cu), Escondida and El Salvador in Chile, Toquepala in Peru, Lavender Pit, Arizona and Malanjkhand, India, which has 145Mt at 1.35% Cu.

The biggest sedimentary copper deposits are found in three basins: the Paleoproterozoic Kodaro-Udokan basin of Siberia, the Neoproterozoic Katangan basin of south-central Africa, and the Permian Zechstein basin of northern Europe.

Sediment-hosted copper deposits are formed by fluid mixing in permeable sedimentary and (more rarely) volcanic rocks. Two fluids are involved: an oxidized brine carrying copper as a chloride complex, and a reduced fluid, commonly formed in the presence of anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacteria.

An oxidized brine containing copper, and a reduced fluid, formed in the presence of anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacteria, are mixed in permeable sedimentary and sometimes volcanic rocks.

For a sedimentary copper deposit to form, all four of the following conditions must be met: an oxidized source rock, a source of brine to mobilize the copper, a source of reduced fluid to precipitate copper and form a deposit, and finally, there has to be the right environment for fluid mixing. It’s been found for example, that sedimentary copper deposits are usually at basin margins where fluid mixing is most likely to take place, or faulting may cause one fluid to invade the site of another fluid. The rock also has to be permeable enough to allow fluids to mix.

When the metals precipitate from fluids circulating in the host rock, they may be deposited in sandstones or shales. It’s a bone of contention among geologists as to whether this happens when the host rocks are formed or later, but all agreed that minerals were deposited when the fluids reached a chemical trap – that is, the point when it was no longer possible for the metals to stay in a solution.

The massive Kamoa sedimentary-hosted stratiform deposit in the DRC is the best example of copper-bearing sandstones.

Sedimentary exhalative deposits formed when hydrothermal fluids contacted a body of water, and precipitated ore. The large deposits in the Zambian copper belt are an example of SedEx-style mineralization.

Red-bed deposits, so named due to oxidation resulting from exposure to the atmosphere, are divided into volcanic and sedimentary. Two examples of volcanic red-bed deposits, the more economic of the two, are the Dzhezkazgan deposits of central Kazakhstan and the Paoli deposit of Oklahoma.

Kupferschiefer deposits are similar to red-beds but larger, even regionally extensive. They typically form in a marine setting, after land is gradually submerged into a shallow sea, then overlain by sedimentary rocks – which formed from the gradual deposition of the carcasses of dead sea creatures, onto the ocean floor.

Kupferschiefers consist of three layers – sandstone, limestone and bituminous shale. Copper-containing fluids migrate up through the sandstone and get trapped by the carbon-rich “kupferschiefer”, which means copper shale in German. This is where most of the mineralization is concentrated, although it can also be found in the sandstone, limestone, or a combination of all three layers.

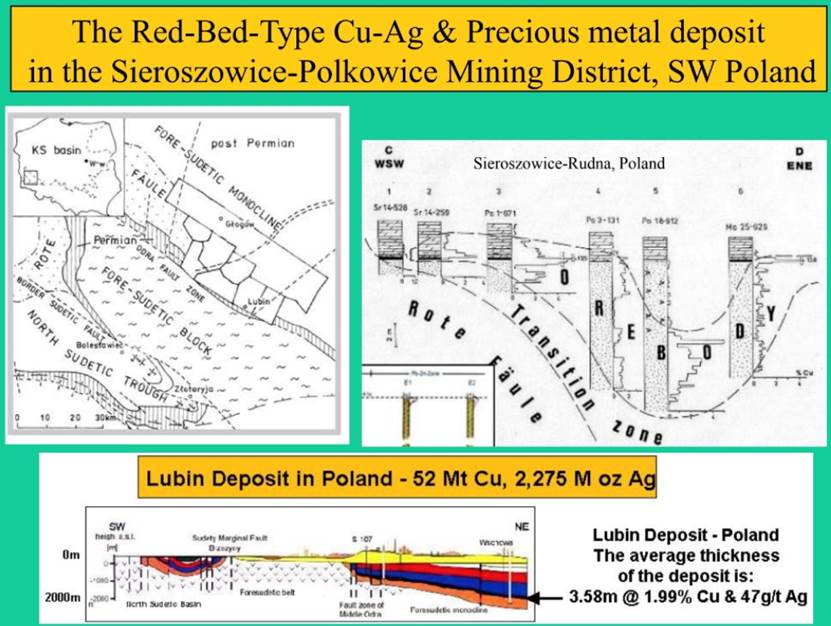

The Lubin model

One of the best examples of Kupferschiefer sediment-hosted copper mineralization is the Lubin-Glogow mining district of Poland:

Geologists describe the sulfide-mineralized Kupferschiefer layer as a typical black organic-bearing shale, up to 1.2 m thick (average 0.3 m), in sharp contact with the underlying Weissliegend or boundary dolomite (Peryt, 1978). In some places the Kupferschiefer is missing, and the Zechstein Limestone (Werra Limestone) is in direct contact with the Weissliegend sandstone. The upper border between the Kupferschiefer and Zechstein Limestone is usually gradational. The Kupferschiefer is developed in three different varieties:

organic-rich (pitchy) shale, clayey shale and carbonate-rich shale. The Kupferschiefer is composed of clay minerals (mostly illite), organic matter, carbonates, sulphides, sulphates, and minor terrigenous quartz and feldspar grains.

The giant Lubin deposit contains a whopping 52 million tonnes of copper and 2.275 billion ounces of silver, at an average thickness of 3.58m containing 1.99% Cu and 47 grams per tonne silver. These are extremely high grades. In British Columbia’s copper-gold country, copper grades average 0.4%.

Lubin is the oldest mine in the Polish Copper Belt, starting in 1968, and the eighth largest copper mine in the world.

In the schematic below, notice the stratified nature of the deposit, with the black shale “Kupferschiefer” layer sandwiched in-between the multi-colored rock layers including sandstone and limestone. The black and white diagram at the upper right shows the U-shaped deposit characterized by columns of mineralization; each column consists of a thin layer of Kupferschiefer locked between the sandstone and the limestone, visualized here as a stack of books or a brick chimney.

Source: A.Piestrzynski et al.

Source: A.Piestrzynski et al.

Copper in Colombia

The Lubin-Glogow of Poland is a good analogue for what Max Resource (TSX-V:MXR) is seeing at its Cesar project in Colombia’s northeastern Guajira state.

The first thing to notice about Colombia’s copper potential is the fact that the Andes mountain range that hosts some of the largest porphyry copper deposits in world, runs right through Colombia. Much of the Colombian part of this immense porphyry belt is hugely under-explored.

This area’s geology is among the most richly mineralized in the world. The South American Cordillera – the southern portion of a chain of mountain ranges that forms the backbone of North and South America – stretches north from southern Chile, up as far as the Aleutian Islands. During their evolution, the Andes hosted a series of magmatic events that led to the formation of a number of large porphyry copper deposits, mostly in Peru and Chile.

Among the largest copper-molybdenum porphyry deposits are at Cerro Verde-Santa Rosa, Cuajone, Quellaveco and Toquepala in southern Peru, and Mocha, Cerro Colorado, Spence and Lomas Bayas in northern Chile. Mainly copper porphyry deposits, with moly and gold kickers, occur in Chile at Collahuasi-Quebrada Blanca, Chuquicamata, Escondida and El Salvador.

Australia’s SolGold (TSX:SOLG) has had success in northern Ecuador, recently announcing the discovery of a new copper-gold-moly porphyry system at its Santa Martha target. SolGold continues to advance its Alpala deposit, located on the northern section of the Andean Copper Belt – which represents nearly half of the world’s copper production.

While there is just one producing copper mine in Colombia, in the northwestern state of Choco, run by Canada’s Atico Mining producing 10,000 tons a year, the government is hoping to diversify from gold, oil and coal, into the red metal.

Recent geological studies found copper mineralization in not only Choco but Antioquia, Córdoba, Cesar, La Guajira and Nariño.

Cesar copper-silver project

Max Resource’s (TSX-V:MXR) two copper targets are Cesar and La Guajira. The company also holds exploration licenses in the Choco and North Choc areas.

In a recent interview, Max’s head geologist, Piotr Lutynski, told AOTH that Colombia’s stratigraphy is similar to his homeland, Poland, and its Kupferschiefer sedimentary copper deposits. KGHM Polska Miedź (KGHM), the sole producer of copper in Poland mined 30.252 Mt of ore at 1.49% Cu and 48.6 g/t Ag, comprising 452 kt of Cu and 1471 tons of Ag in 2018.

“The copper and silver are very classical elements likely to be in sedimentary deposits like Colombia,” said Lutynski, noting he has worked in similar mineralization in Peru. “It’s the same stratigraphy with the sandstone below the limestone on top and the Kupferschiefer equivalent in the middle.”

A crew at its Cesar copper project has been looking for surface outcrops, that Max thinks could be the tip of the iceberg of a giant sediment-hosted copper system below surface.

If there’s an orebody at Cesar, underneath those outcrops, Max would be looking at a major discovery. The company has identified a 70 X 20-km copper-silver target area with up to 2% combined copper and silver. Twelve outcrops spread over 9 km indicate mineralization is open in all directions.

Copper and silver assay results from six more locations are pending.

Max is also using historical drill results from the Colombian government, seismic data and drilling logs gleaned from historical oil and gas exploration.

It’s interesting to note that energy companies looking for oil and gas in the sedimentary basin at Cesar possibly missed core intervals indicative of copper deposit (or groups of deposits) since O&G companies were looking for hydrocarbons.

Lutynski compared the exploration horizon of sedimentary copper deposits to a garden with a door buried vertically, with the top edge parallel to the surface. Using seismic indicators, you search for the door(s), and follow it down. As opposed to a porphyry deposit, which is the garden.

Outlining a porphyry is difficult and expensive because so much drilling has to be done to figure out what is the size and shape of the deposit. With sedimentary copper, the trick is to find the copper outcroppings, then go to your seismic/ oil and gas drill log data to find the orebody that may be dipping beneath the soil cover. After that, it’s a matter of identifying the best drill targets.

Max’s goal is to get to that point, bring in a major copper company as a partner, that can help finance a drill program at Cesar and bring it to a resource, then complete the rest of the steps (PEA, prefeas, feasibility study, permits, etc.) required to build a mine.

Lutynski said he expects costs and the amount of ground disturbance to be minimal, noting that with Kupfershiefers, drilling can take place at 6-km spacings, versus porphyries which must be drilled every few hundred meters along strike.

North Choco news

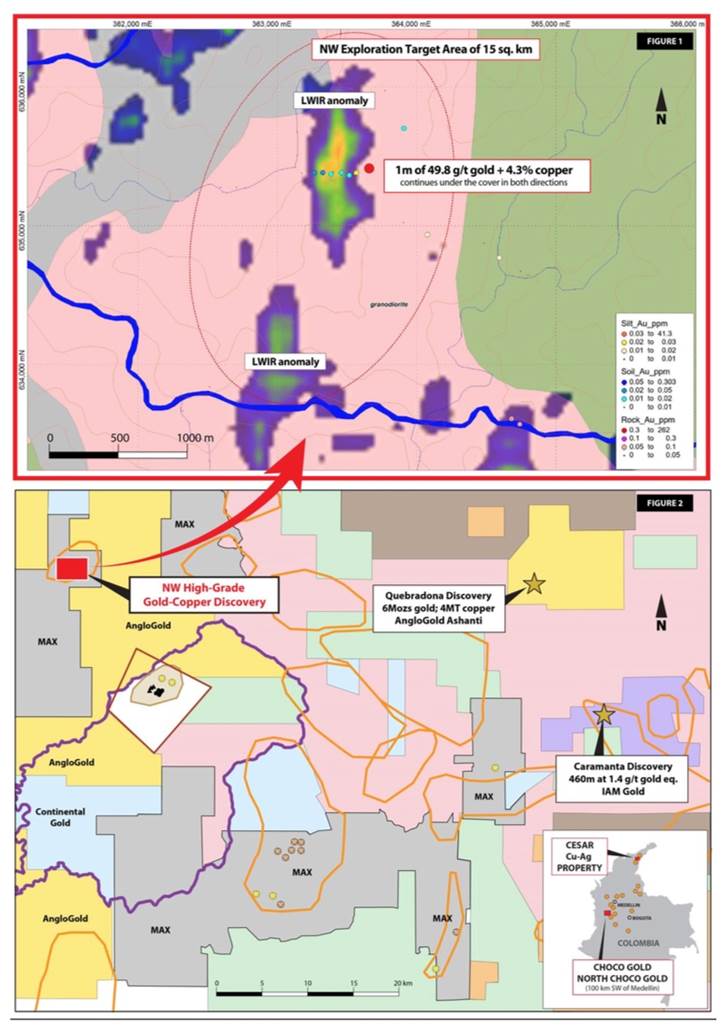

Meanwhile Max is continuing to work its Choco and North Choco exploration areas, releasing news this week about its North Choco Gold Project.

A rock chip sample collected over a one-meter interval returned an off-the-charts 49.8 grams per tonne gold and 4.3% copper. According to Max, the discovery could indicate the start of a new mineralized zone, considering that it is open in all directions and appears to be structurally controlled within the host rock.

Max decided to sample the 15-km NW Gold-Copper Discovery area, based on historical work by Ingeominas, along with the results of a recent LWIR (long wave infrared) survey. A regional silt sampling program carried out in September and October highlighted creeks draining the discovery area, returning values of 28 parts per billion (ppb) gold and 338 parts per million (ppm) copper, and 11 ppb gold and 200 ppm copper, respectively.

Future work will focus on mapping and sampling along strike to extend the zone, and on locating additional parallel zones.

The revised North Choco project, located 80 km southwest of Medellin, contains about 400 square kilometers of mineral applications covering four prospective areas including 10 historic gold mines and the NW Gold-Copper Discovery.

According to Max, AngloGold Ashanti’s 2005 Quebradona gold-copper discovery and IAMGold’s 2010 Caramanta gold-copper discovery are both in a similar geological environment to the NW Gold-Copper Discovery area.

Quebradona hosts a 2014 inferred mineral resource of 604 million tons grading 0.65% copper, 0.32 g/t gold, 4.4 g/t silver and 116 ppm molybdenum representing an inferred 6.1Moz gold & 3.95Mt copper and hosts four additional porphyry centers.

Caramanta contains five porphyry centers and has recorded several drill intersections over 1 g/t gold, including 460.6m at 1.4 g/t gold equivalent.

The company for the time being has stepped away from its conglomerate-based Choco Precious Metals Project due to access issues.

Conclusion

North America has a lot of mining knowledge and expertise when it comes to discovering and mining copper porphyry deposits. Here in British Columbia we have built a reputation for building quality copper-gold mines from enormous copper-gold and copper-molybdenum porphyries, such as Red Chris and Highland Valley.

The same cannot be said for sedimentary copper deposits. While North America has some – for example the Calumet and Kearsarge deposits in Michigan, and Oklahoma’s Paoli – the knowledge base is mostly in Europe and Africa.

Max Resource is onto something at Cesar that could be very unique for the region – a sediment-hosted copper-silver deposit right in the heart of the Andean Copper Belt.

SolGold (TSX:SOLG) is doing good work in neighboring Ecuador, but it’s a 37-cent stock with 2 billion shares (fully diluted) outstanding! At 12,993,427 shares outstanding and currently trading at 0.10 cents/sh, MRX offers far more upside and shareholder value on any discovery.

It’s early days of course, but I like what I’m seeing, and Max’s approach to it. The exploration program seems straight-forward enough. Identify the copper outcrops, through geochemical surveys and good old-fashioned boots and hammers, then “go deeper”, using historical drill results, seismic data and oil and gas drilling logs. The grab samples taken so far are high grade. Are they indicative of what lies beneath? More work needs to be done to determine that.

Remember though this is a sedimentary deposit, not a porphyry. Defining a deposit does not require hundreds of drill holes, which is beyond the scope of any junior. The orebody is more likely to resemble a series of stratified columns, or stacked books, than a bag of flour with millions of grains of rice. A lot of it can be defined without drilling, making the project realistic both technically, and financially.

We understand that Max has shifted focus, from gold to copper-silver. But we’re also told they haven’t given up on Choco and North Choco – as Tuesday’s excellent sample results indicate. A gold junior needs to be solid, in terms of management and treasury, but it also needs to be nimble. When the situation changes, good juniors adjust, and pivot to the better opportunity. We see a very interesting play developing in Cesar; I’ll be following developments there closely and communicating them to my readers.

Max Resource Corp

TSX.V:MXR, FSE:M1Di

Cdn$0.10 2019.11.01

Shares Outstanding 12,993,427m

Market cap Cdn$1.29m

MXR website

***

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions.

Richard owns shares of Max Resource Corp and MXR is an advertiser on his site.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.