MINE in BC, a clean alternative to DRC’s dirty trade in cobalt

2020.01.08

Ever wonder what’s inside your cell phone, behind the long trail of text messages, emails and pretty Instagram photos? Most people these days are inseparable from their phones (see what happens when you try to confiscate your teenager’s mobile), but their adoration for these ubiquitous 21st century gadgets might wane a little, if they knew about all the metals in a phone and how they got there.

Among the metallic components that enable a handheld device’s electronics to download and send files quickly, improve video and gaming capabilities, and present a vivid, sharp screen, are gold, lithium, aluminum, cobalt, copper, lead, nickel, silver, zinc, platinum and palladium.

Over the years, one of these metals has come under particularly close scrutiny: cobalt. Tech giants like Apple, Microsoft, Dell and Samsung are increasingly being asked to defend their supply chains to ensure they are sourcing cobalt responsibly. That’s because two-thirds of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where human rights advocates like Amnesty International have reported rampant safety violations at ramshackle mine sites, and widespread use of child labor. The unstable African country has made cobalt the “blood diamonds” of the electronics industry.

Apple has said it plans to buy cobalt directly from mining companies, (although that was nearly two years ago and nothing’s come of it) to verify mining practices, and maintain a secure, steady supply of cobalt – an indispensable battery ingredient whose stability and high energy density allows batteries to operate safely and for longer periods.

Until recently cobalt usage was dominated by metal alloys, due to the metal’s resistance to high temperatures, strong magnetism and wear/corrosion resistance. These characteristics make cobalt a perfect fit for aerospace superalloys, cutting tools, binders for cemented carbides, permanent magnets and semi-conductors.

Over the last 20 years however, the market for cobalt has shifted to chemicals, particularly compounds needed for rechargeable batteries, which represent 78% of chemical cobalt demand. Other cobalt chemicals are used in catalysts to refine petroleum, and to make plastics, steel-belted radial tires, dryers, pigments, food additives and agricultural products.

Cobalt is the common denominator between the two main types of EV batteries, nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) and nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM).

A battery cathode needs cobalt to provide stability and to maintain its cycle life – ie, how many times the battery can be discharged and recharged without loss of capacity.

Nickel is popular with EV battery-makers because it provides the energy density that gives the battery its power and range. Increasing the amount of nickel in a battery cathode ups its power/ range, but add too much of it and the battery becomes unstable, ie. vulnerable to overheating and a shortening of its life-span.

Nickel is used in two of the dominant battery chemistries for EVs, the nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) battery used in the Chevy Bolt (also the Nissan Leaf and BMW i3) and the nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) battery manufactured by Panasonic/Tesla.

Nickel can also be found in a mobile phone’s electronic connections, capacitors and batteries.

Cobalt and nickel are interesting to watch because both face challenges in ramping up production to meet rising demand for them in EV batteries. They are also worthy of comparison because cobalt is usually mined as a by-product of nickel and copper.

In this article we’re taking a deep dive into how nickel and cobalt are mined and distributed, up the supply chain into the electronic devices we hold in our hands. Think of it as a written journey, from stone to phone.

Nickel

Nickel deposits come in two forms: sulfide or laterite. About 60% of the world’s known nickel resources are laterites. The remaining 40% are sulfide deposits.

The main benefit of sulfide ores is that they can be concentrated using simple flotation, meaning processing costs are much lower than nickel laterite deposits.

However, large-scale sulfide deposits are extremely rare. Existing sulfide mines are becoming depleted, with precious few to replace them.

Only one nickel sulfide deposit has been discovered in the past decade, Nova-Bollinger in Western Australia which is now in production.

There are two types of nickel, Class 1 and Class 2. Lower-grade Class 2 nickel is primarily used to make stainless steel. Global nickel consumption is dominated by China, which imports low-grade nickel “pig iron” (NPI) from the Philippines and Indonesia, totaling around half of all shipments.

Sulfide deposits provide ore for Class 1 nickel users which includes battery manufacturers. They purchase the nickel product known as nickel sulfate, derived from high-grade nickel sulfide deposits. It’s important to note that less than half of the world’s nickel is suitable for the biggest growth market – EV batteries.

As we proved in a previous article, there is a looming shortage of battery-grade nickel. Tesla has expressed concern over whether there will be enough of it.

According to BloombergNEF, demand for Class 1 nickel is expected to out-run supply within five years, fueled by rising consumption by EV battery suppliers.

So, here’s the nickel industry’s dilemma: how to keep the traditional market intact, by producing enough NPI and ferronickel to satisfy existing stainless steel customers, in particular China, while at the same time mining enough nickel to surf the coming wave of EV battery demand?

The solution appears to be, mine the high-grade sulfide deposits (what’s left of them) and the laterites to produce nickel sulfate needed for EV batteries. Read about the challenges of HPAL technology in this AOTH article, and why we remain bullish on battery metals.

Cobalt

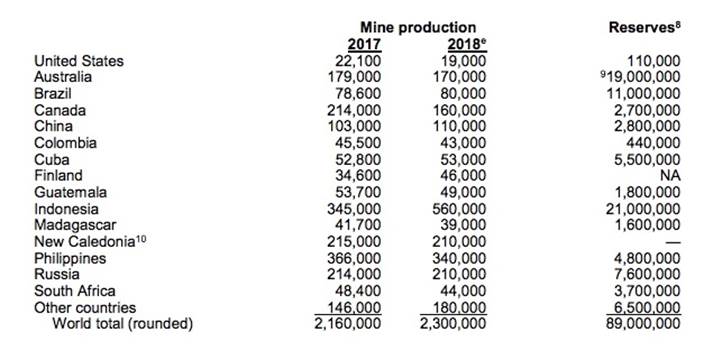

As mentioned, 64% of the world’s cobalt production comes from the DRC; trailing far behind are, in order, Russia, Australia and Cuba.

The USGS notes the vast majority of cobalt resources are locked within stratiform copper deposits in the DRC and Zambia. The remaining tonnage is found in nickel-bearing laterites in Australia and Cuba. Over 120 million tonnes of cobalt have also been identified in manganese nodules and crusts on the ocean floor.

In 2018 the DRC produced 90,000 tonnes of cobalt, up from 70,000t in 2017. Canada mined just 3,800 tonnes and the US even less, 500t.

Allegations of human rights abuses including child labor have put the DRC in the wrong kind of international spotlight. BMW, Daimler (owner of Mercedes), Volkswagen and Apple are among big-name companies that source components from the DRC, and facing pressure to make their supply chains transparent.

In fact a number of US tech companies have been accused of benefiting from cobalt extracted by child-miners in the DRC. In December Cnet reported that International Rights Advocates, a non-profit, filed a lawsuit in a Washington court on behalf of 14 plaintiffs – guardians of children either killed or seriously injured in tunnel or wall collapses. The defendants in the suit, writes Cnet, are Apple, Microsoft, Dell, Tesla and Alphabet, Google’s parent company.

Apple responded to the allegations by saying if its suppliers don’t stop employing underage or involuntary labor, it will stop working with such companies. The iPhone maker says 20 companies have lost its business due to non-compliance, including two cobalt and five “3TG” (tungsten, tantalum, tin and gold) smelters in 2018.

Dell said it is investigating the allegations and Google said its code of conduct “strictly prohibits” child labor and endangerment, Cnet states in the article.

A key player in the cobalt market is China, which imports 98% of its cobalt from the DRC and produces around half of the world’s refined cobalt.

Beijing is heavily invested in the DRC, as it works towards its goal of mass EV adoption, and ensures its factories have access to clean-technology raw materials like cobalt, lithium and graphite.

In a $9 billion joint venture with the DRC government, China got the rights to the vast copper and cobalt resources of the North Kivu in exchange for providing $6 billion worth of infrastructure including roads, dams, hospitals, schools and railway links. China controls about 85% of global cobalt supply, including an offtake agreement with Glencore, the largest producer of the mineral, to sell cobalt hydroxide to Chinese chemicals firm GEM. China Molybdenum is the largest shareholder in the major DRC copper-cobalt mine Tenke Fungurume, which supplies cobalt to the Kokkola refinery in Finland.

Blame the DRC and China

In fact it is the China-DRC connection that really forms the basis of the problem mining cobalt in the Congo.

One of the poorest countries in the world, the Democratic Republic of Congo has suffered from decades of war and poor governance. After the state-owned mining company collapsed in the 1990s, artisanal mining (by hand, without the use of machinery) became an important source of livelihood, especially during the Second Congo War of 1998 to 2003. In fact President Kabila encouraged people to hand-mine since the government was unable to revive industrial mining.

A new mining code in 2002 established that artisanal mining can only take place within special “exploitation zones”, where mechanized mining isn’t possible. However because the government has created so few zones, most miners work illegally, either in unauthorized areas or by trespassing on claims owned by mining companies.

The government estimates 20% of the DRC’s cobalt exports are dug by artisanal miners in Katanga province – a workforce of between 110,000 and 150,000.

A 2016 report by Amnesty International details the nature of this dangerous work.

The miners use their bare hands and rudimentary tools to dig out or collect the cobalt, found in a dark grey rock known as heterogenite. The report states:

In some places, the miners dig deep underground to access the ore. These miners, who are mainly adult men and are known in the DRC as creuseurs, work underground in tunnels and use chisels, mallets and other hand tools. They fill sacks with the ore, which are then tied to ropes and pulled by hand out of the mine shafts, which can be tens of metres deep.

In September 2015, 13 miners died when a tunnel collapsed in an artisanal mining colony; 17 were killed in four separate accidents the week earlier. An underground fire the same month killed five miners and injured 13.

In June, 2019, at least 43 artisanal miners died in a tunnel collapse while digging for cobalt at a mine in Kolwezi owned by Glencore, Amnesty International said in a news release.

Children as young as 6 work underground and on surface, often digging for cobalt in discarded tailings piles:

All of the tasks carried out by children in the mines require them to carry heavy sacks of mineral ore, sometimes carrying loads that weigh more than they do. Children reported carrying bags weighing anywhere between 20 – 40 kg. Carrying and lifting heavy loads can be immediately injurious or can result in long-term damage such as joint and bone deformities, back injury, muscle injury and musculoskeletal injuries. The children interviewed by researchers described the physically demanding nature of the work they did. They said that they worked for up to 12 hours a day in the mines, carrying heavy loads, to earn between one and two dollars a day.

Along with deaths or injuries resulting from collapsed tunnels, exposure to dust containing cobalt can lead to lung disease and other respiratory illnesses such as asthma and decreased pulmonary function. Repeated handling of the material may cause dermatitis.

The DRC Mining Code does not provide any guidance on safety equipment or how to handle substances that may pose a danger to human health. The US Center for Disease Control advises people working with cobalt to wear respirators, impervious clothing gloves and face shields. However according to the Amnesty report, when researchers visited five mining areas and interviewed close to 90 workers, they found most did not have even basic protective equipment. They told the researchers that underground mines were un-ventilated and that dust build-up affected them.

Where does the cobalt go after it’s mined? Amnesty researchers followed vehicles carrying cobalt ore from artisanal mines in Kolwezi to a market town where independent traders – mostly Chinese – buy the ore. These traders then sell the ore to larger companies, in the DRC, which process and export it.

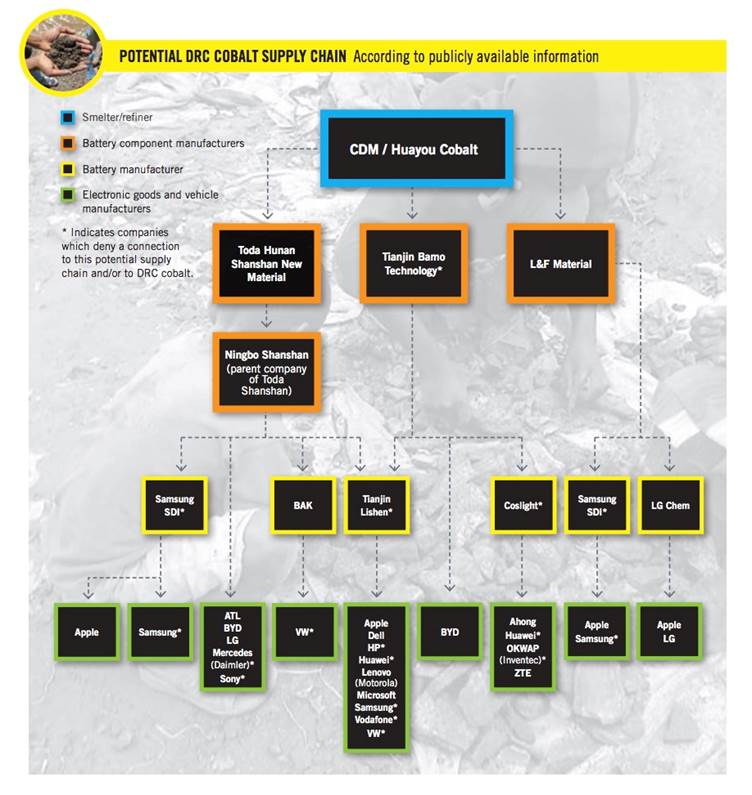

According to the report, the company at the center of this trade is Congo Dongfang Mining International (CDM), a subsidiary of China-based Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Company Ltd (Huayou Cobalt), one of the world’s largest manufacturers of cobalt products:

Operating in the DRC since 2006, CDM buys cobalt from traders, who buy directly from the miners. CDM then smelts the ore at its plant in the DRC before exporting it to China. There, Huayou Cobalt further smelts and sells the processed cobalt to battery component manufacturers in China and South Korea. In turn, these companies sell to battery manufacturers, which then sell on to well-known consumer brands.

In 2014 Huayou Cobalt’s three largest customers, all lithium-ion battery component manufacturers, were Toda Shanshan New Material of China, Tianjin Bamo, also Chinese, and L&F Material, based in South Korea.

From this manufacturing process there are at least seven companies an investigator would need to check with in order to discover who mined the cobalt and how it was extracted: the artisanal miner, the trader, the DRC refiner, the Chinese refiner, the battery component manufacturer, the battery maker, and finally, the consumer brand, like iPhone or Samsung. Also consider that no country (including China and South Korea, where a good chunk of the world’s EV battery makers are based) legally requires companies to publicly report on their cobalt supply chains.

We can therefore see how easy it is for unethical mining to take place in the DRC. Amnesty reports that, according to its research, companies along the cobalt supply chain are failing to conduct adequate human rights due diligence. As the smelter, CDM and Huayou Cobalt are at a critical point in the supply chain and are expected to know how the cobalt that they buy is extracted, handled, transported and traded. They should be able to identify where it is mined, by whom and under what conditions (including whether human rights abuses or any form of illegality are taking place). Amnesty International and Afrewatch conclude from Huayou Cobalt’s response that it was failing to take these crucial steps and carry out due diligence in line with the OECD Guidance [a five-step process for all companies involved in the mineral supply chain to follow], which has been accepted by the Chinese Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters. It is failing to respect human rights and there is a high risk that Huayou Cobalt is buying (and subsequently selling) cobalt from artisanal mines in which children and adults work in hazardous conditions.

In its report, Amnesty International found many companies the group talked to denied sourcing their cobalt from the DRC or Huayou Cobalt, even though they were listed in the documents of other companies found to be buying from the Chinese company. Amnesty also revealed that the Chinese government has given millions of dollars in subsidies to Huayou Cobalt and that the company’s third-largest shareholder is a government fund that supports Chinese companies in Africa. It appears that, even though Huayou Cobalt is nearly three-quarters privately owned, it functions like a state-owned enterprise.

Inomin Mines (TSX.V:MINE)

The companies involved in this unethical trade, akin to “blood diamonds” only worse since it involves children, and the buyers, at the end of the production line, are some of the largest, most powerful technology companies in the world, clearly have no wish to be identified in an industry that is essentially using modern-day slaves.

The electrification of the global transportation system however is demanding more and more cobalt for EVs. Demand for smart phones that also need cobalt isn’t going anywhere but up. One solution is to crack down on DRC’s artisanal miners – bring in armed personnel to kick the miners out and protect cobalt resources, force companies to be more transparent, shame Apple, Google, Microsoft etc. – but none of these measures is likely to change a system that has become deeply entrenched. And who are we, the developed west, to say to a DRC artisanal miner, “you can’t make a living because we prefer children to be students rather than workers.”

Thankfully, there is another way, and that is developing nickel and copper deposits containing cobalt right here, in North America. The United States and Canada both host such deposits; the US is thought to have a million-tonne resource, mostly in Minnesota.

Inomin Mines (TSX-V:MINE ) is a junior exploration company focused on nickel and cobalt in British Columbia.

BC is best known for its porphyry copper/ gold mineralization. These deposits contain the largest resources of copper, significant molybdenum and 50% of the gold in the province. Examples are big copper-gold and copper-molybdenum porphyries such as Red Chris and Highland Valley. Large, undeveloped porphyry deposits along the North American Ring of Fire include Galore Creek in BC and the Pebble project in Alaska.

According to the Nov. 4 news release, Inomin has laid claim to two properties in central BC, Beaver and Lynx, not far from Williams Lake and 150 Mile House.

The 7,528 hectare Beaver and 12,662 hectare Lynx are located between two major BC mines overlying world-class porphyry deposits – Taseko’s Gibraltar mine and Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley. Gibraltar is the second largest open-pit copper mine in Canada.

Mining “close-ology” dictates the importance of developing a mine that is nearby, or located within similar geology, to an existing producer(s). Even better if that producer is mining a porphyry. Porphyry deposits are usually low-grade but large and bulk-mineable, making them attractive targets for mineral explorers.

Highlights from a 2014 drill program at Beaver included 157.3 meters, 106.6m, and 86m, all containing 0.18% nickel and 0.01% cobalt. These uniform assays are low grade, but don’t let that dissuade you.

A little back-of-the envelope math by yours truly shows the potential for an impressive nickel-cobalt deposit of significant scale to interest a major mining company or funding partner. For the details, read Inomin eyeing monster BC nickel sulphide deposits

Inomin has a Class 1 nickel project in a Tier 1 jurisdiction. BC was in the top quarter of all countries surveyed in the Fraser Institute’s latest investment attractiveness rankings.

In fact Inomin’s Beaver and Lynx properties have all five elements a nickel junior must have to interest a major: size, grade, scalability, longevity and infrastructure. The company already has an advanced nickel system at Beaver, proven by drilling, and a similar but potentially much larger nickel opportunity at Lynx.

Conclusion

Combine all of these pluses with the fact that nickel and cobalt are both facing supply restrictions, therefore, higher prices for the foreseeable future, along with the seriously questionable ethics of mining cobalt in the DRC, and you might start thinking there are Class 1 projects in much better and safer mining jurisdictions, like Inomin’s nickel/ cobalt project in BC, that could, potentially, feed the battery and car-makers of the future.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Richard does not own shares of Inomin Mines (TSX-V:MINE). MINE is an advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.