Metals, cars, beef and beer: How tariffs will hurt Americans – Richard Mills

2025.03.22

The world is bracing for April 2nd. That is the date that US President Trump has set for invoking “reciprocal tariffs” on countries that tax or limit markets for American goods.

“April 2 is a liberating day for our country,” Trump was quoted telling reporters on Air Force One on Sunday evening, according to The Hill, adding that it is a chance to “start taking back some of the vast wealth that has been taken from us.”

The April 2 deadline applies to Canada and Mexico, who were given a one-month reprieve from 25% across-the-board tariffs in early March. The walk back applied to all goods covered under the US-Canada-Mexico Agreement (USCMA). The USCMA applies to about half of imports from Mexico and 36% of imports from Canada.

Included in that group of goods are autos and auto parts. Not included is Canadian potash imports, which are now subject to a 10% duty, along with Canadian energy imports. Gasoline prices have reportedly already gone up in the northeastern United States.

With Trump’s one-month pause on tariffs, Canada put a hold on its planned second round of tariffs on over 4,000 US goods until April 2. That second wave of tariffs is worth CAD$125 billion. The first wave of Canadian import tariffs worth CAD$30B was launched on March 6.

On March 12 the Trump administration put 25% tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum. The Canadian government responded with nearly $30 billion in countervailing duties — 25% tariffs on a list of steel products worth $12.6 billion and aluminum products worth $3 billion, as well as additional imported US goods worth $14.2 billion.

Here we take a deep dive into the tariffs’ effects on silver, copper and gold — along with three sectors that personify America: cars and car parts, beef and beer.

Silver

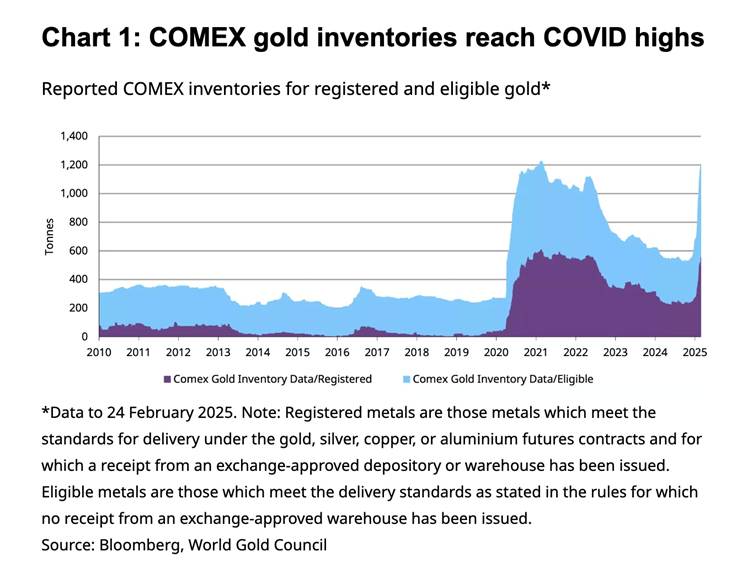

Traders are shipping gold and silver at a breakneck pace from London and other places to New York for storage on the COMEX, the primary futures and options market for trading metals such as gold, silver, copper and aluminum. The traders want their metal to arrive in New York before tariffs kick in on April 2.

Bloomberg reported that Comex-tallied inventories of silver have expanded to the highest level ever in data going back to 1992 after surging by 40% so far this quarter, a record rise.

The demand for COMEX-inventoried silver has sent the precious metal on a 17% tear so far this year, with silver futures going even higher.

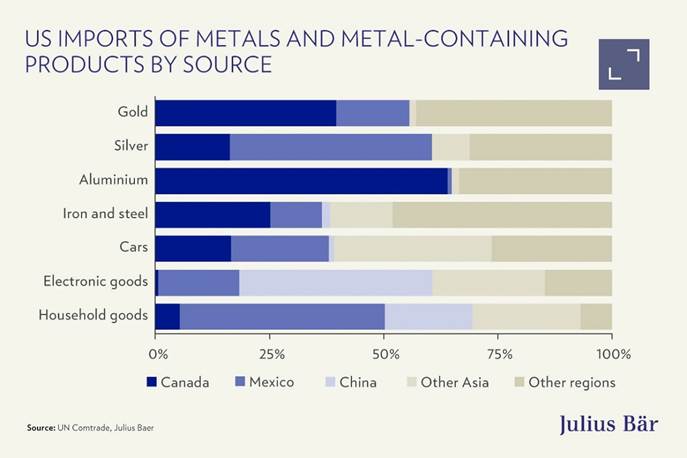

The United States imports about 70% of its silver from Canada and Mexico — the two countries most targeted by the Trump tariffs. Bloomberg noted the CAD$30 billion in retaliatory tariffs includes silver.

Another Bloomberg article reported that 15 million ounces of silver were added to the COMEX in the five weeks prior to Jan. 9. Daniel Ghali, senior commodity strategist at TD Securities, said stockpiles in the London market have been drained heavily following four years of severe shortfalls in global mined silver production, and further outflows risk creating a knock-on spike in prices.

“We expect the drain to be significant in scale,” he said. “This is the silver squeeze that you can buy into.”

A Feb. 1 article by the Scottsdale Mint noted that Trump’s actions on tariffs “leave no carve outs or exceptions for bullion and monetary metals.”

Two of North America’s favorite bullion coins — Mexican Libertads and Canadian Maples have become tariff targets. A $30 silver coin could jump an additional $7.50 overnight come April 2. Moreover, according to Scottsdale Mint, 80% of US silver grain used in the bullion market comes from abroad — mostly Mexico.

This isn’t just about a few sovereign coins; your favorite cast bars and rounds could get caught in the crossfire as US-based dealers and mints work to find alternative raw material providers.

Those like Trump who think it can all be supplied domestically will soon get a reality check: despite big Alaska mines like Hecla’s Greens Creek and Teck’s Red Dog mine combining for over 16 million ounces annually (plus another 11.2Moz from mines in Nevada and Idaho), US mines only satisfy about 17% of US silver demand.

To put these numbers in stark perspective, U.S. mines produce approximately 28 million ounces of silver annually, while domestic demand reaches roughly 162 million ounces. This dramatic shortfall – about 134 million ounces – underscores why international trade plays such a crucial role in America’s silver market.

Gold

The threat of tariffs, and their negative effects on the global economy including inflation and lower growth has propelled the gold price to record highs — as of this writing $3,052 an ounce.

Like silver, gold in US dollars is rising due to extraordinary demand for it in New York, where metal traders are sending large quantities prior to tariffs kicking in at the beginning of April.

According to the World Gold Council, via CNBC, more than 600 tons, or almost 20 million ounces, had been transported into the city’s vaults since December 2024. That number is almost certainly low, since it is as of Feb. 28.

“There are concerns that imminent tariffs on Canada and Mexico will affect both gold and silver,” said Nicky Shiels, head of metals strategy at MKS Pamp.

“The biggest concern is that there could be a blanket tariff on all imports into the U.S. and that this could also apply to gold,” Nikos Kavalis, managing director of Metals Focus, agreed.

WGC notes the spread between the COMEX active gold futures contract and spot gold reached as much as US$40/oz to $50/oz, significantly above the $13/oz average from the past two years.

As the supply chain for gold shifts to COMEX vaults in New York, the availability of metal in London has been declining, Kavalis added. At the same time, large 400-ounce gold bars are being pulled out of London to refineries around the world where they can be melted and refined into 1-kg bars, the standard measure for COMEX vaults.

Data from the London Bullion Market Association showed that gold reserves in London’s vaults fell for a third consecutive month in January. A Reuters report citing Swiss customs data showed gold exports from Switzerland to the US were their highest in 13 years that month. Singapore also shipped more gold than it normally would do to the United States.

In a commentary, the World Gold Council said the influx of gold from (mostly) London to New York caught many gold observers by surprise, as the country is more or less sufficient in its gold needs, being both a significant producer and a consumer.

Actually, the US imports a lot of gold from other countries, with Canada the leading provider followed by Switzerland, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa, according to data from OEC World.

In a commentary by wealth manager Julius Bar, he notes that For gold and silver, the impact of tariffs is primarily on the refining value chain. The US imports a significant amount of gold and silver doré from Canada and Mexico for refining, which has now become more expensive. Some of this material might be rerouted to Europe.

Another article by APMEX Knowledge Center points out that tariffs affect gold and silver prices indirectly through various economic factors such as inflation pressures, currency valuation, economic uncertainty, and central bank policies.

The article gives three examples of when tariffs caused the prices of gold and silver to increase: 1987 US tariffs on Japanese electronics; 1995 US tariffs on Japanese automobiles; 2002 US tariffs on steel imports; 2012 US tariffs on Chinese solar panels; and in 2018, when the US imposed 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from the European Union.

Copper

Like silver and gold, traders are also front-running copper ahead of potential tariffs on the metal come April 2, although Citi Bank thinks a copper tariff won’t come into effect until the fourth quarter.

On March 19 Bloomberg reported between 100,000 and 150,000 tons of refined copper is expected to arrive in the US in coming weeks. If the full volume arrives in March, it would beat the record of 136,951 tons set in January 2022:

Commodities traders including Trafigura Group, Glencore Plc and Gunvor Group are redirecting large volumes of metal earmarked for Asia to the U.S. The quantity is so big that traders are booking additional warehousing space in New Orleans and Baltimore to accommodate the shipments.

In February Trump launched a probe into potential new tariffs on copper, saying they would help rebuild US production.

Whatever the results of the probe, the reality is that the United States is in no position to set up a protectionist barrier against copper imports. The reason is simple: the US relies too much on foreign copper supplies and building new mines in the US takes up to 20 years.

Imports account for about half of US copper usage, up from just 10% in 1995. Chile, Peru and Canada account for the majority of imported copper. The United States though is a relatively small market for Chile and Peru. Most of their exports go to China.

S&P Global produced a report in 2022 projecting that copper demand will double from about 25 million tonnes in 2022 to 50Mt by 2035. The doubling of the global demand for copper in just 10 years is expected to result in large shortfalls — something we at AOTH have been warning about for years.

Forbes argues that if Trump is fixated on luring manufacturing to the States by throwing up tariffs, he should exempt imports of raw materials especially critical minerals like copper:

Whereas tariffs on imported finished goods may provide incentives to produce in the United States, tariffs on production inputs are strong disincentives to do so because they raise U.S. manufacturing costs…

The “mineral of electrification” is essential to manufacturing and construction in traditional and emerging U.S. industries, alike. Electrical uses of copper, which include power generation and transmission; wiring in offices, hotels, and other structures; telecommunications; and electrical and electronic products account for about 75% of total copper demand. But copper is also used intensively in transportation equipment and infrastructure, industrial machinery, and a growing number of products. Lower copper prices enable greater profitability among U.S. manufacturers, and more investment.

Aside from making manufacturing more expensive, copper tariffs are a foolish policy because the mining, refining and forging stages of the supply chain are so integrated. According to Forbes, The U.S. portion of the industry employs over 65,000 workers, generates $77 billion in output, and depends on access to imports of refined copper to succeed.

The Hill agrees with Forbes that the supply chain for copper is too closely meshed for tariffs to work. Author Marc L. Bush writes that “Trump is right to target copper as a national priority, but he’s going about it the wrong way.”

Like semiconductors and pharmaceuticals [and autos — Rick], copper is the product of a complex supply chain. The four key stages include mining, smelting and refining, semi-fabricating and manufacturing final goods. The U.S. has different challenges at each stage, but tariffs are not the solution to any of them.

Bush identifies the problems with bringing a mine online, noting the US ranks second-last globally in terms of required lead times — 29 years, just ahead of Zambia’s 34 years. Potential new copper mines face permitting challenges. For example, development of Rio Tinto and BHP’s massive Resolution copper mine in Arizona is on hold, facing opposition from native Americans.

Second, the US only has two operating copper smelters, one secondary smelter and 17 refineries. Decoupling from China, which controls 97% of global copper smelting and refining capacity, is a fool’s errand.

“Trump’s proposed copper tariffs will put America last, not first,” Bush asserts.

Even with tariffs, American copper buyers have little choice but to keep buying imported metal given that the US consumes twice as much as it produces. (Bloomberg)

Mining Weekly concurs that The US industrial sector will have the most to lose from potential US tariffs on copper, analysts say, with costs seen rising significantly during what would be a lengthy process of reviving domestic mining and refining of the metal.

US copper production dropped 3% last year from 2023, following an 11% decline that year.

The Northern Miner quotes the former CEO of Codelco — the world’s largest copper mining company — saying that US tariffs on copper will only serve to drive up prices because domestic producers can’t make up the shortfall.

“Implementing such a measure as part of protectionist policies to boost domestic copper production would not be beneficial for the U.S.,” Marcos Lima said in February.

“The only thing that will happen is that the price of copper in the United States will rise,” Lima told the ‘Miner via email. “It’s impossible for the country to increase its production levels overnight.”

Bloomberg argues that not only will tariffs raise copper prices in the United States, hurting end users, they will also exacerbate the looming global copper shortage.

Reportedly, American buyers are already looking to source more copper from Chile and Peru, because copper from Mexican and Canadian mines could get diverted to Europe to avoid paying US tariffs.

Less raw copper entering the US means less copper will be shipped to China for refining:

Tariffs could cause China to refine less copper — to the tune of 10,000 to 20,000 tons a month within the first three months. That’s in a global market that Goldman already expected to be facing a 180,000-ton deficit this year.

Copper surpassed $11,000 a ton Thursday, March 20 on the COMEX in New York, hitting $11,270/t ($5.11/lb) at 1 pm ET. The price represents a 13% premium on London Metal Exchange copper which just crossed $10,000/t.

COMEX copper prices are now up 27% since the start of the year, while the LME price is about 14% higher — incentivizing traders and producers to keep moving copper to New York.

Autos and auto parts

The North American auto industry was just getting back on its feet from a semiconductor shortage during covid-19 and rampant inflation on new and used vehicles — the average price of a new car in Canada rose 43.2% between 2019 and 2025, and used car prices rose 39.5% during the same timeframe, according to data from AutoTrader.com.

Now the industry has a new threat to profitability in tariffs.

According to CNBC, Trump’s proposed tariffs on goods from Mexico and Canada would hit automotive suppliers harder than automakers.

For now, products that meet USMCA rules of origin can avoid the 25% tariffs until they come into effect on April 2. However, the expectation of tariffs has pulled down the stock prices of suppliers such as American Axle & Manufacturing Holdings, Magna International and Adient.

To be USCMA-compliant, 75% of the vehicle’s content must be sourced from the US, Canada or Mexico. Major parts such as engines and transmissions are assembled locally, however BMW said its vehicles being produced in Mexico are not USMCA-compliant, largely because the engines are imported from Europe.

CNBC says auto suppliers have been adamant that they can’t take on a 25% cost increase on non-compliant USMCA parts, that would be in addition to levies on steel and aluminum.

The Financial Post quoted J.D. Power earlier this month, who estimated that 25% U.S. tariffs and counter-tariffs could add $6,000 to the price of a new vehicle, which is a 9.2% increase given that the average new vehicle in Canada costs $64,600, according to Autotrader.

Analysts at S&P Global Mobility say that vehicles more exposed to tariffs will slow or cease production.

Eventually, many economists say the tariffs could lead to inflation or a recession, which will affect interest rates and consumer behaviour, including whether to purchase a vehicle.

“With these tariffs in place, we would expect to see vehicle sales in these countries contract substantially,” Andrew Foran, an economist at TD Economics, said in a Jan. 28 note.

Beef

Nothing says America like burgers, steaks and beer.

Unfortunately though, Americans will be paying more for all three thanks to Donald Trump’s asinine trade war.

At the end of February, Reuters reported that the average beef price in US cities was up 43% since 2020. Global beef prices are up 34%. After years of drought, North American cattle herds are thin, with the US herd the smallest in 74 years, and Canada’s the smallest in 36 years.

Herd thinning takes place when feed costs are so high that ranchers can’t afford to keep a large number of cattle.

Canada, the number 8 beef exporter and 10th largest cattle producer, exports over half of its beef production, with 75% going to the US.

Like auto parts and copper, the two markets are intertwined. As Reuters notes, Historically, cows, calves, breeding stock, slaughter animals and beef-in-boxes have flowed across the U.S.-Canada border as if it were not there. Canada imports many young cattle from the U.S., fattens them, slaughters them, then sends the meat back to the U.S. Tariffs would upend this process.

Also like copper, the United States will have a hard time replacing Canadian beef. The country is already in a beef deficit and importing from as far away as Australia, Reuters says, noting Canadian beef fills in where there is not enough US beef.

The tariffs will have major price implications on either side of the border. One Canadian feed lot owner quoted by Reuters estimates one truckload of fattened cattle would face a $28,000 bill due to tariffs. The same owner thinks US buyers could either refuse to pay more than they would for US cattle, or just not buy Canadian animals at all.

As for where the price increases will be felt, Food Logistics reports consumers will feel the effects of a 25% tariff on imported beef at grocery stores, restaurants and butcher shops.

The publication notes the United States imports a lot of lean beef from Canada and Mexico, which gets blended with fattier domestic beef to make affordable ground beef and processed products. “With tariffs in place, those imports become more expensive.”

Grocery store shoppers are likely to notice the price hikes first, followed by fast food chains and casual dining restaurants.

Another interesting point is what happens when Canadian beef shipments slow across the border, or stop altogether. According to Food Logistics, cheap beef found at US supermarkets is inexpensive because major national retailers and even local stores source a portion of their beef from Canada. Replacing imported Canadian beef with American product will raise prices.

And therein lies the rub. Why can’t US cattle ranchers simply raise more beef to make up for less Canadian imports? As mentioned, the US cattle supply is at a low level even before tariffs kick in, due to drought and high feed costs. “Ranchers can’t just magically produce more cattle overnight,” states Food Logistics. “Raising quality beef takes time, care and resources.”

The comparison to building a new copper mine is instructive. In the US this can take up to 20 years. In the meantime, how is the States going to get enough copper to make up for lower imports from tariffed countries? How is it going to raise enough beef for domestic consumption? These are issues the Trump administration has not bothered to research.

In the long run, the risk is that beef prices stay high, prompting consumers to switch to cheaper alternatives like pork and chicken. Arguably, this happened a long time ago among lower-income groups in Canada and the United States.

There are other trade war risks. If Canada and Mexico retaliate, and Canada almost certainly will, US beef exports could take a hit, hurting American ranchers. The countervailing duties could be too much for smaller, independent farms, leading to industry consolidation where the only companies left are big players that produce lower-quality beef. The loser once again is the American consumer.

The Calgary Herald recently published an article on how 25% tariffs will affect Alberta beef producers. Amid the trade spat, the article says Canadian cattle groups have been looking to diversify export markets, process more domestically and push for improvements to government support programs…

The province exported $8.79 billion worth of food and agriculture to the U.S. in 2023, of which bovine meat accounted for $2.89 billion. U.S. beef exports have been steadily increasing in recent years, jumping nearly 21 per cent between 2022 and 2023.

One-fifth of harvest-ready cattle in Alberta are exported to the United States.

One cattle rancher quoted by the Herald said an expected drop in beef prices and rising input costs would not be good for their small family business. An upside of tariff threats has been increased local support for their direct-to-consumer beef, said Kim Wachtler, whose family has been operating Burke Creek Ranch for 135 years.

Beer

Rising input costs for breweries due to tariffs have put a sour taste in the mouths of beer drinkers on either side of the 49th parallel.

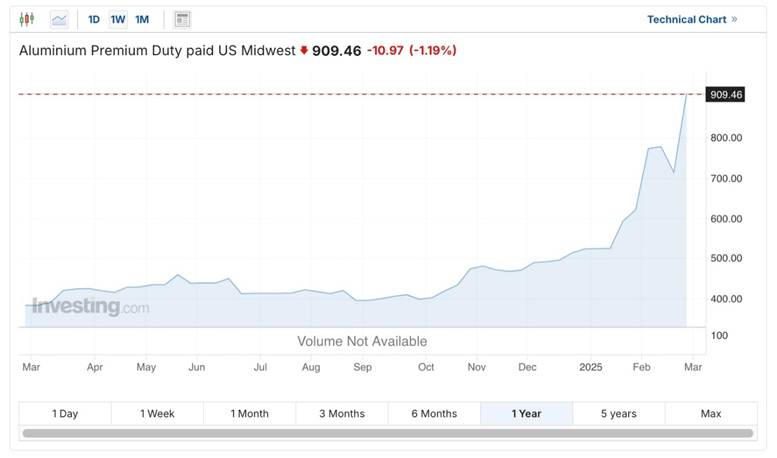

The issue boils down to the aluminum cans that most beer is now sold in. According to the Globe and Mail, if Trump’s 25% tariffs on aluminum continue, Canada’s beer industry will be hit with a $330 million increase to the annual cost of cans.

In fact, brewers face a double tariff whammy. The US has imposed a 25% tariff on raw aluminum imports, while Canada has levied a 25% tariff on $30 billion worth of goods imported from the United States. This includes finished beer cans or flattened sheets of aluminum that can be made into cans, per the Globe.

Like copper, auto parts and beef, the Canada-US beer industry is highly integrated. Take aluminum, the metal of choice for beer cans. Canada exports a lot of raw aluminum to the US, and imports large volumes of finished aluminum cans. The Globe provides the numbers. Last year we exported more than $10.6 billion worth of unwrought aluminum to the States. Canadian brewers used about 3.7 billion cans, almost 20% of which were made in America.

Why doesn’t Canada just make more aluminum cans and avoid the tariffs that way? The problem is another symptom of integration: Canada does not operate any aluminum rolling mills that produce large, flat sheets of aluminum that can be cut and formed into beverage cans.

The US aluminum industry needs Canadian raw aluminum just as much as the Canadian industry needs refined aluminum (cans). While the country has a large base of semi-manufactured product makers, it only has four operating primary smelters to supply them, according to Reuters.

Those four smelters produced 670,000 tonnes of metal in 2024, compared with US consumption of around 4.9 million tons. Imports of primary metal totaled almost 4.0 million tons, of which 70% came from Canadian smelters.

This interdependence between the two countries means a can is likely to cross the border at least twice on its journey from mine to six-pack, so consumers paying for the final product could see the trickle-down effect of a double tariff.

Conversely, the price of beer is highly elastic, so many brewers will be reluctant to pass on the added aluminum costs to their customers for fear of losing them to a cheaper brand. These brewers will have to “eat the cost” of the cans, possibly resulting in lower production runs.

The good news for aluminum producers and the bad news for end users is that the premium on US aluminum prices have hit record highs.

The CME Midwest premium, reflecting the cost of unwrought aluminum delivered to a US fabricator over and above the London Metal Exchange price, briefly jumped to almost $1,000 per ton over the LME price on the threat of 50% tariffs on Canadian metal before retreating on news of the truce with Ontario Premier Doug Ford. (Reuters)

The publication notes that, as the US aluminum premium has surged to all-time highs, European premiums have been falling. The divergence suggests that some suppliers to the United States are already looking to avoid Trump’s tariffs by re-directing sales to Europe.

The Silver Bullet lining in all this? Trump’s recent threat to impose 200% tariffs on alcohol from Europe could benefit the struggling US beer industry, which has been under pressure due to declining sales and shifting consumer habits.

“Beer is just not in the crosshairs of this. Beer looks like an island of stability right now,” Trevor Stirling, managing director and European beverages analyst at Bernstein, told “Squawk Box Europe”, via CNBC.

Conclusion

Donald Trump is the worst kind of manager in that he makes decisions without first considering the consequences.

As we have underlined in this article, the tariffs imply an inability to comprehend the interconnectedness of the markets in question, whether we are talking about copper, auto parts, beef or beer.

In many cases a product crosses the border several times from its raw to its finished form. Tariffs and countervailing duties will interrupt trade flows and hike input costs in both Canada and the US. Most of the time these will be passed onto the consumer. The end results are likely to be a hike in inflation, higher interest rates to fight inflation, a reduction in consumer spending, and a slowdown in GDP. Two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth is by definition a recession and many observers think this is what may be coming down the pipeline.

The threat of tariffs has knocked the stuffing out of the US stock market and propelled gold to record highs. Metal traders are furiously shipping gold, silver and copper to COMEX vaults in New York, ahead of tariffs on metals likely to be put in place on April 2.

Then again, Trump could again delay the tariffs or make adjustments to them. Tariffs on copper could dent demand for it in the United States and shift the supply flow from the US to tariff-free Europe and Asia. It’s likely the price would drop initially but could rebound due to additional imports from China.

If the 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada, and reciprocal tariffs on countries that tax or limit markets for American goods come to fruition on April 2, the wholly unnecessary disruption to global trade will almost certainly benefit safe havens gold and silver.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Share Your Insights and Join the Conversation!

When participating in the comments section, please be considerate and respectful to others. Share your insights and opinions thoughtfully, avoiding personal attacks or offensive language. Strive to provide accurate and reliable information by double-checking facts before posting. Constructive discussions help everyone learn and make better decisions. Thank you for contributing positively to our community!

3 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

#reciprocaltariffs #US-Canada-Mexico Agreement #USCMA

Food inflation has historically been the catalyst for many popular uprisings, from the French Revolution to the (US) Flour Riot of 1837, the Richmond Bread Riot of 1863, and more recently, the Arab Spring. When people can’t afford to eat, when work has dried up and they can no longer feed their families, when housing represents more than two-thirds of income, a point of reckoning is reached.

It’s extremely hard to see how any of the chaos and confusion Trump is generating with his policies is going to benefit the US in the short, medium or long term.