Melting ice exposing mineral wealth

2020.08.22

Emily Riedel steps gingerly as she walks along the ice hugging the shoreline off Nome, Alaska.

The ice is thinner than normal this year, only about a foot, certainly not stable enough to hold a snowmobile. Every step in her heavy snow boots risks disaster, were she to plunge into the freezing -21C Bering Sea.

“The ice is so thin right here. It’s open ocean in February,” says Riedel, lifting her eyes to the horizon, as she is filmed for the Discovery Channel’s ‘Bering Sea Gold’ television series. “This isn’t supposed to happen until May.”

Riedel is a gold prospector, hoping to strike it rich in the Arctic, one of the toughest jurisdictions for extracting the precious metal on Earth. The Arctic is bitterly cold and extremely isolated, its climate and terrain unforgiving.

At least these ice miners are well-compensated. At today’s prices, collecting just 250 ounces will earn one miner US$400,000. Even Riedel’s modest goal of 60 ounces will deliver a sweet payoff – close to $100,000 – enough to get her expanded fleet fully equipped and ready for next summer’s prospecting season.

Ice mining is as dangerous as it looks. The process begins with finding the ‘Goldilocks’ thickness of ice – not too thick, not too thin. An exploratory hole is then cut with an ice auger, and a camera fed in, to take pictures of the sea bottom. They’re looking for cobble, where the gold is trapped in large pockets of rock. In summer the dredges move on open water, making the search as easy as pulling anchor, but in winter, large dive holes must be sawed out of the ice. Moving the operation each time a new hole is cut can take days.

A diver descends into the jade-green abyss, carrying a hand-held dredge. When he reaches bottom, the diver looks for visible gold, holding a flashlight. As he turns over the rocks with thick rubber gloves, the diver places the “ore” into the dredge and it’s sucked up to surface for later sorting at the makeshift mining camp.

“It’s surreal. Once you go under that sheet of ice there’s no margin for error,” says Shawn Pomrenke, of Northwest Golddiggers. “One small mistake could cost you your life.”

The self-described “Mr. Gold” figures it’s worth the considerable effort, expense and risk. One half of his Tomcod claim, 10 miles west of Nome, he estimates is worth $80 million.

Warming Arctic

The small Siberian town of Verkhoyansk is one of the coldest places on Earth, with the mercury plunging to -50 degrees Celsius in winter. In June, a prolonged Arctic heatwave recorded a sizzling 38 degrees C.

That is 18 degrees higher than the town’s average maximum daily temperature in June, and well beyond the extreme heat and cold that is sometimes felt in Eastern Siberia.

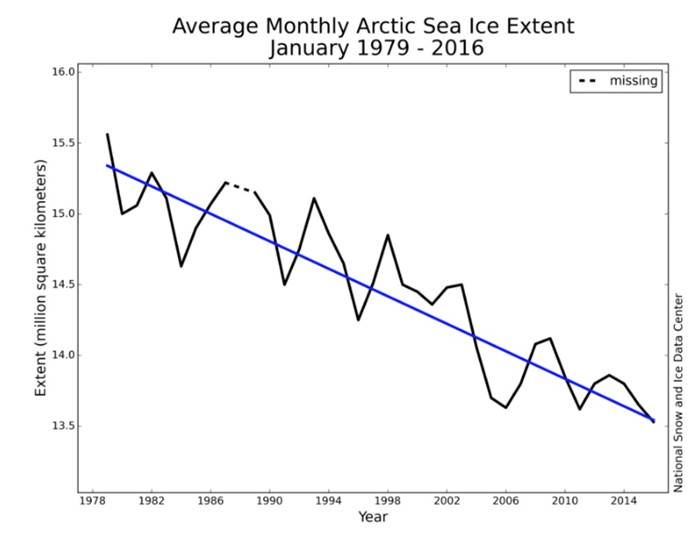

Over the past 30 years, the Arctic has warmed more than any other region – by 3.1 degrees from October to May.

Resource opportunities

For decades the Arctic was largely off limits to mineral exploration because the land was buried under hundreds of meters of snow and ice. Global warming is changing that picture.

Higher Arctic temperatures have meant new opportunities for mining companies, which are submitting applications for extraction all the way from Canada through Greenland to Finland.

Among the metals sought after, are gold, nickel, rare earths and uranium.

The World Economic Forum states,

A warmer climate will make mining possible in parts of the Arctic that were previously inaccessible. The region holds many of the raw materials that will form a key part of green technologies, like the rare-earth elements used in batteries for electric cars and wind turbines.

In Greenland, Alcoa is building a massive smelter powered by cheap hydroelectricity. The US aluminum company recently signed an MOU with the Greenland government, to complete a feasibility study for the smelter, which has a 340,000 tonnes per year capacity.

The Citronen zinc-lead project is one of the world’s largest undeveloped zinc-lead resources, containing a resource in excess of 13 billion pounds of contained Zn and Pb.

Along with holding vast amounts of untapped minerals and petroleum, Greenland contains about 10% of the world’s fresh water. However, with temperatures hitting record highs, forecasts estimate that the island’s ice sheet will disappear in the next 80 years, leading to a 7-meter increase in the world’s oceans, and drowning some of the world’s largest coastal cities.

The Canadian Arctic too, is taking on increasing importance for mining companies.

In Nunavut, there are now three producing gold mines – the Hope Bay Doris mine operated by TMAC Resources; Meadowbank, owned by Canadian mid-tier gold miner Agnico-Eagle; and Meliadine, another Agnico-Eagle property, which opened in 2019.

According to the Financial Post, Agnico-Eagle’s CEO, Sean Boyd, has emerged as a vocal advocate for greater federal investment in the region, to unlock the vast mineral resources in the north. This includes greater infrastructure such as roads and energy projects but also higher education facilities to train the population.

“We have championed the North and its enormous potential to our international investors and to every politician we’ve ever spoken with,” Boyd said in a speech at the Canadian Club in downtown Toronto in November [2019].

Shrinking ice caps

Canada is estimated to be warming twice as fast as the rest of the world, due to our northern geography.

Ice coverage in the eastern Arctic has dropped below the historical median every year since 2004, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada. In September 2019 it fell 5%, to the lowest on record.

“I’ve seen first-hand strong indications that these remote regions are experiencing climate warming at rates far higher than normal. Canada’s Arctic glaciers have been shrinking at unprecedented rates,” says David Burgess, a scientist with Natural Resources Canada who has been studying ice caps for 20 years.

The higher temperatures are also melting glacial ice in Greenland and Iceland, and reduce free-floating polar ice coverage, leading to a dangerous climate “feedback loop”.

NASA states that feedback loops may double the amount of warming caused by carbon dioxide alone. The disappearance of snow and ice at the poles exposes dark ocean to sunlight, warming the oceans. When ice covers the poles, the sunlight is reflected back to the atmosphere, keeping the oceans cool. As the planet keeps warming, more ice disappears, exposing more water, further raising ocean temperatures, and sea levels.

Melting permafrost

As more of the Arctic tundra becomes ice-free, melting permafrost releases methane – a greenhouse gas 20 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

One-fifth of Arctic permafrost is now vulnerable to global warming, according to a University of Guelph biologist, whose research was published in ‘Nature’, a scientific journal. In the Central and Southern Mackenzie Valley, it has warmed about 0.2 degrees C per decade since the mid-1980s.

Natural gas is mostly methane (CH4), and methane is over 25 times more efficient than carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere over a 100-year period. (the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says methane is 86 times more damaging than CO2 over a 20-year period). Scientists estimate methane contributes about 25% to global warming.

The escape of huge amounts of methane after the permafrost has melted in the Arctic is a key feedback loop we have previously identified as being a major accelerant of global warming. For more read Climate Armageddon

In a feature article, The Washington Post illustrates how an “Arctic cauldron” was discovered by a graduate student who has studied some 300 lakes dotted across the Arctic tundra.

A Mexican scientist also studying the lake found it was producing two tons of methane gas per day – the same amount of methane gas that would be farted from about 6,000 dairy cows.

In an earlier published study, Katey Walter Anthony and her husband, also a scientist, warned of the dangers of thermokarst lakes, which form when the permafrost melts.

They found that the continuing growth of these lakes — many of which have already formed in the tundra — could more than double the greenhouse gas emissions coming from the Arctic’s soils by 2100. That’s despite the fact that the lakes would cover less than 6 percent of the total Arctic land surface.

This could be a key reason why atmospheric methane levels since 2006 have averaged 25 million tons more per year.

According to the article, if Walter Anthony’s findings are correct, the impact of thawing permafrost would mean the equivalent of adding two more Germany’s to the planet in terms of carbon emissions. And that doesn’t count the existence of the strange Arctic cauldrons which emit methane at a much faster rate.

Similar bubbling lakes have been found in the tropics.

There is recent evidence to show that the amount of methane in the atmosphere is rising.

In July, ‘Nature’ magazine reported that global methane emissions have risen nearly 10% over the past two decades, reaching a record 596 million tonnes in 2017, the latest year of available data.

Scientists reported atmospheric concentrations of the gas are now over 2.5 times above pre-industrial levels, and are primarily driven by agriculture and the natural gas industry.

About a third of methane emissions come from bacteria in natural wetlands, that produce gas when decomposing organic material, suggesting that melting permafrost is likely to be a significant contributor to higher methane emissions in future.

Most methane leaks come from flaring excess NG instead of putting it into a pipeline. Think methane emissions are no big deal, just a cost of doing business? The journal ‘Nature’ published a study saying that the US oil and gas industry emits 13 million tonnes of methane a year, which is 60% higher than the EPA’s estimate.

The biggest methane leak in US history occurred in California in 2015. It took SoCal Gas nearly four months to plug the leak at the Alison Canyon gas field – during which an estimated 109,000 tonnes of methane was released into the atmosphere. While that sounds bad, the methane emissions from one natural gas field – the sprawling San Juan Basin in the US southwest – emitted 291,162 tonnes of methane in 2014, according to the EPA. The Front Range tight gas formation in Colorado reportedly leaks 19.3 tons of methane an hour.

Receding glaciers

In British Columbia, glacial recession is occurring at an alarming pace, from an environmental perspective, but like in the Arctic, this is presenting exciting opportunities for mineral explorers.

In the Golden Triangle mineral corridor of northwestern BC, over the last decade there has been a resurgence of mining interest, driven partly by new road and power infrastructure built by the BC government, and receding glaciers revealing fresh mineralization.

According to an earths science professor quoted by the CBC, the glaciers in the Golden Triangle starting forming about 7,000 years ago, and are thinning about half a meter to a meter per year. Over 30 years, the glaciers have shed about 100 feet of thickness.

Mountain Boy Minerals

For junior miners like Mountain Boy Minerals (TSX-V:MTB), this is an opportunity to find minerals in locations that for thousands of years were hidden beneath a thick shield of ice and snow.

On May 27, Mountain Boy Minerals announced the kick-off to its 2020 exploration program at its American Creek project. The two-phase campaign first involves a LiDar aerial survey of the property, as well as further prospecting and mapping to confirm the drill locations. Three targets will then be drilled in Phase 2, with the objective of confirming the geological model, ie., that the various mineralized occurrences are surface expressions of a large geological system, analogous to the neighboring Premier District. This district, which produced 2.5 million ounces of gold and 60 million oz of silver, is about to go back into production.

The drills will target three areas, according to an Aug. 6 new release .

- MB Silver: Drilling around the historic Mountain Boy mine will follow up the 2006 drill program, which intersected multi-kg silver values over significant widths. The drilling is intended to test the high-grade zone for continuity, both along strike and at depth.

- Dorothy: The second target is the northern extension of the mine’s silver-bearing veins onto the recently optioned Dorothy property.

- Wolfmoon: The IP survey will focus on the third target – the recently discovered Wolfmoon zone.

Mountain Boy Minerals is active in one of the best jurisdictions for base and precious metals exploration. Between past-producing gold mines and current compliant resources, BC’s Golden Triangle has yielded a whopping 200 million gold ounces, putting it in the same league as the Carlin Trend in Nevada, the second-largest repository of gold on Earth.

The Triangle is also one of only a few billion-ounce silver districts in the world.

Mountain Boy is ready to get results on multiple targets, which hopefully will provide evidence of a district-scale opportunity that will create an enormous amount of interest, from the market and larger mining companies.

MTB has assembled a large land position centered around its flagship American Creek project and zeroed in on three targets for its summer drill program. Work this year on the other projects is intended to set them up for larger programs next year, perhaps funded by joint venture partners.

CEO Lawrence Roulston and his team are going for high-grade in the Golden Triangle. As he states, hitting a discovery hole on any of these targets could light this thing up. Expect a slow ramp-up in the first phase and growing interest once the drills start turning in late summer to fall.

Mountain Boy’s performance over the past three months has been nothing short of spectacular. Stockholders who owned MTB in early May and held on, have nearly quadrupled their capital.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Facebook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Richard owns shares of Mountain Boy Minerals. MTB is a paid advertisers on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.