Melting ice, Arctic scramble

2019.05.18

In August 2007, a pair of Russian submersibles dropped to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean and planted a flag at the North Pole.

The audacious move by Russia to stake a symbolic claim on the Arctic, was swiftly condemned by the West. Under international law, no one country owns the very top of the world, nor the waters around it which have been covered in ice for millions of years.

Twelve years later, the Arctic has been transformed by rising temperatures. Once considered too remote, too cold, and too inhospitable for civilization, the Arctic has been transformed by climate change.

Over the past 30 years, the Arctic has warmed more than any other region on earth – by 3.1 degrees in the coldest six months of the year, October to May.

Melting sea ice has caused ocean levels to rise, from seven to eight inches over the last 117 years, NASA states, with the most rise occurring since 1993. The expansion of ocean water as it warms also causes higher sea levels. The latest International Panel on Climate Change report predicts sea levels rising between 52 and 98 centimeters by 2100 if nothing is done to stop rising temperatures. An increase of 65 centimeters, or roughly two feet, is expected to cause significant flooding in coastal cities.

When sea ice is lost, the sunlight is no longer reflected back to the atmosphere, but rather gets absorbed into the open ocean. This exacerbates ocean warming and forms a warming cycle. Warmer water temperatures delay the growth of ice in fall and winter, and the ice melts faster in the spring, exposing patches of open ocean for longer periods during summer, and further warming the ocean.

According to NASA, Arctic sea ice measured in September – when it is thinnest – is now declining at a rate of 13.2% per decade. Since 1971, 8 trillion tonnes of land ice was lost across the Arctic regions of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Scandinavia and Russia. The ice is melting at an incredible 14,000 tonnes a second according to a new report, ‘Key indicators of Arctic climate change: 1971-2017’.

CBC quotes William Colgan, a senior researcher at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, and one of the report’s authors, saying that amount of melt is enough mass to tip the earth.

“The planet now points to a slightly different North Pole because we’re redistributing too much mass on the earth right now through melting of glaciers, and then letting that water run off into the ocean and get spread around towards the equator,” he says.

Along with calving glaciers, shrinking ice caps and disappearing sea ice, evidence of Arctic warming can also be seen in the thawing of permafrost.

It had been assumed that the melting of the top layer of tundra that remains frozen year-round would be a slow process, releasing carbon as the ground thawed. In fact, the permafrost melt is happening much quicker than expected. Scientists studying the phenomenon are finding “Instead of a few centimetres of thaw a year, several metres of soil can destabilize within days. Landscapes collapse into sinkholes. Hillsides slide away to expose deep permafrost that would otherwise have remained insulated,” states CBC.

In some places the thaw is happening so fast, the earth is swallowing up equipment left there to study it, Global News reports. The fast-melting areas are known to contain the most carbon, meaning that permafrost is probably going to release 50% more greenhouse gases than expected, including methane which is far more efficient than CO2 at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

One-fifth of Arctic permafrost is now vulnerable to global warming, according to a University of Guelph biologist, whose research was just published in ‘Nature’.

Environmentalists, First Nations and other residents in the sparsely populated Arctic decry the effects of global warming, but where some see loss of animal habitat, like polar bears, in the melting ice, and a disappearing way of life for Inuit hunters, others see opportunity.

This article takes a deep dive into what is happening in our northern backyard, the Arctic – what is at stake, who are the main players, what are the issues?

Let’s start by looking at the “territory grab” that is happening in the Arctic, as polar nations jostle to control their share of a vast expanse of ocean and land that is rich in natural resources, and as the ice retreats, is beginning to open up new trans-polar shipping routes that hold great promise for seaborne trade.

Territory grab

In fact, at the center of the Arctic, the Geographic North Pole, there is no land to grab. Unlike the South Pole, which sits on a continental land mass, the North Pole is in the middle of the Arctic Ocean amid shifting sea ice. All lines of longitude converge at the North Pole, which is diametrically opposite the South Pole.

A few interesting facts about the North Pole from Wikipedia: The depth of the ocean has been measured by Russian submersibles at 4,261 meters, or just under 14,000 feet. The nearest land is said to be Kaffeklubben Island off the north coast of Greenland 700 km away, and the closest settlement is Alert in Nunavut, Canada. Robert Peary, a US Navy engineer, is generally credited as being the first explorer to reach the North Pole in 1909, accompanied by American adventurer Matthew Henson and four Inuit men. In 1937, Soviet scientists set up the world’s first North Pole ice station about 20 km from the pole. Russians annually establish a base called Barneo close to the North Pole that operates for a few weeks in early spring.

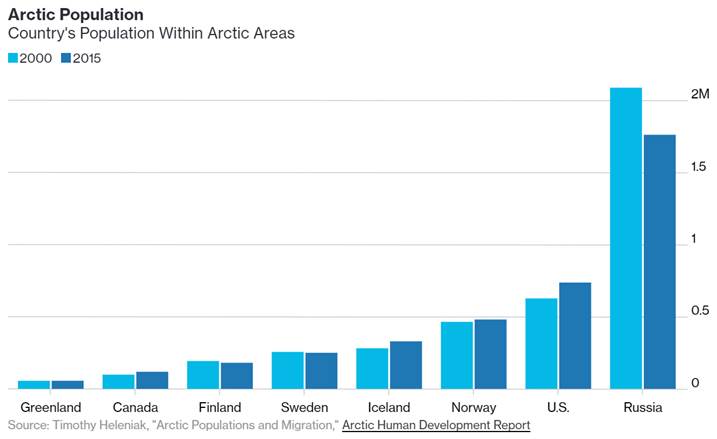

Who has jurisdiction over the North Pole, the Arctic Ocean, inland seas and land masses that we refer to as the Arctic? Control over all of this 20-million-square kilometer territory including “exclusive economic zones” (EEZs), is divided among the eight Arctic states: Canada, the United States, Russia, Norway, Denmark/Greenland, Iceland, Sweden and Finland.

EEZs are zones prescribed by the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Within these zones, a state has the right to explore and extract marine resources including hydrocarbons underneath the seabed, and energy produced from water and wind. EEZs stretch out 200 nautical miles from the coast. An Arctic nation, within the EEZ, has rights below the the ocean surface, but nobody owns the surface – they are known as international waters. The North Pole and the surrounding Arctic Ocean, for example, are not owned by any one country.

This sort-of shared ownership has caused some disputes over what is considered to be an international seaway and who has the right of passage. Six of the eight Arctic nations regard parts of the Arctic seas as their own. A country that ratifies the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea has 10 years to make claims on a continental shelf that gives it rights to resources on or below the shelf’s seabed; Norway, Russia, Canada and Denmark all have claims on continental shelves below their EEZs. The US has signed the convention but hasn’t ratified it.

When the Arctic Ocean was covered with a thick sheet of ice, this arrangement worked reasonably well, with little conflict. But the disappearance (and for now, re-appearance) of the ice has stirred the imaginations of polar nations intent on taking advantage of more accessible natural resources and shipping routes.

If current climate trends continue, scientists estimate that the Arctic Ocean will be ice-free by mid-century. To clarify, that means sometime between 2030 and 2050, in September, the month with the least amount of ice cover, the Arctic Ocean will be entirely uncovered by ice.

Recall that Russia was the first to claim Arctic ownership beyond its territory, in 2007. Russia has also reportedly been expanding infrastructure along its northern coast to exploit natural gas reserves.

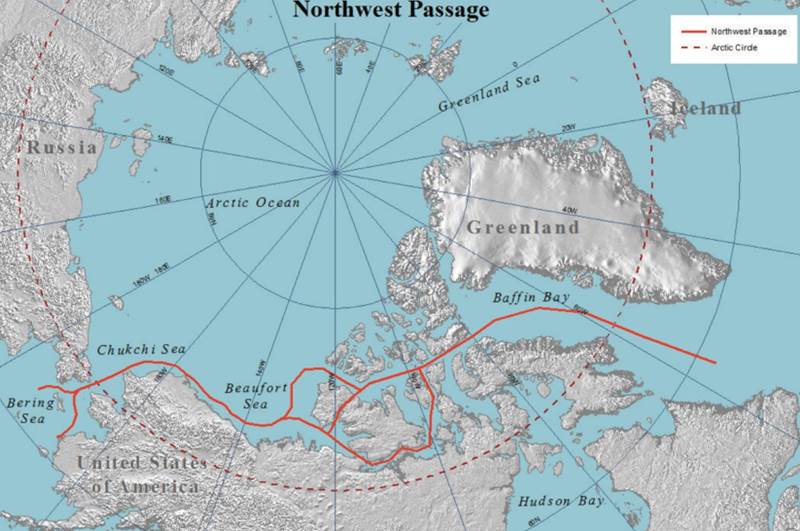

Canada claims ownership of the Arctic Ocean archipelago. To asserts its claims, the country has created a new research center, is developing autonomous submarines, and conducting search and rescue exercises in anticipation of growing ship traffic in the Northwest Passage.

But countries’ investment in the Arctic is rather un-even. Despite having the second largest amount of land mass within the Arctic Circle, behind Russia, Canada has spent very little, as has the United States with only the northern third of Alaska considered to be Arctic.

The big spenders are Russia and Norway. National Geographic notes that Russia has “greatly expanded its military forces in the Arctic, becoming, by most measures, the dominant cold-weather player.” Russia’s northern fleet is the largest in the world at 60 ice breakers and another 10 under construction. Norway has expanded its ice-capable fleet to 11 ships. Both countries have invested heavily in oil and gas development.

This year a House of Commons committee is urging the Canadian government to work with NATO to identify Russia’s military intentions in the north and to shore up Canadian Arctic sovereignty.

According to Global News, the recommendation came “one day after Russian President Vladimir Putin outlined an ambitious plan to increase Russia’s Arctic presence, including expanding its fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers and building new ports and other infrastructure.

The Russian leader invited foreign companies to invest in projects at both ends of the Arctic shipping route, from Murmansk in Russia’s northwest to the Kamchatka Peninsula in the east.

With Arctic sea ice melting, Putin said he plans to dramatically increase Russian cargo-ship traffic in northern shipping lanes.”

Earlier this year Russian newspaper Izvestia reported that Russia’s military will resume fighter patrols in the North Pole for the first time in 30 years. CTV News states:

Recent Russian moves in the Arctic have renewed debate over that country’s intentions and Canada’s own status at the top of the world.

The newspaper Izvestia reported late last month that Russia’s military will resume fighter patrols to the North Pole for the first time in 30 years. The patrols will be in addition to regular bomber flights up to the edge of U.S. and Canadian airspace.

Russia has been beefing up both its civilian and military capabilities in its north for a decade.

Old Cold-War-era air bases have been rejuvenated. Foreign policy observers have counted four new Arctic brigade combat teams, 14 new operational airfields, 16 deepwater ports and 40 icebreakers with an additional 11 in development.

Bomber patrols have been steady. NORAD has reported up to 20 sightings and 19 intercepts a year.

To be fair, Canada and the US operate bases in the Northwest Territories and Alaska capable of dispatching troops, aircraft and submarines. NATO countries regularly train for cold-weather conflict including a massive training exercise last October in Norway called Trident Juncture. The two weeks of war games involving 50,000 troops from 31 nations, was the largest training exercise since 1989.

However, compared to Russia, and for that matter, China, not even a polar nation, Canada’s Arctic efforts pale. The government has no official Arctic policy and there is an extensive list of unfulfilled infrastructure promises including no high-speed Internet. The only significant project has been a paved road completed to the Arctic coast at Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories.

Lately China has become more interested in the Arctic, eyeing less ice cover as an opportunity to expand its ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI). The ‘Polar Silk Road’ would be an extension of its ambitious plans for a series of BRI infrastructure spends designed to create a trading orbit in southern Asia. The Polar Silk Road includes a potential shipping route across the Pacific and the development of energy and mining resources in the region, plus fishing and tourism.

The country is hoping to diversify its energy resources away from the Persian Gulf and Africa, by investing in Russia’s Yamal LNG complex and in Norway’s oil and gas fields. Between 2012 and 2017 China spent around $90 billion on Arctic infrastructure and natural resource extraction.

In 2013 China was granted observer status on the Arctic Council.

A recent article in The Hill explains in detail the reasoning behind China and Russia’s greater involvement in the world’s northern-most reaches:

The Chinese need to sustain economic growth. One way to do that is to improve their access to natural resources, particularly energy, rare-earth minerals and sea-based protein. They also would like to develop an alternative shipping route from Europe to Asia that is not dependent on the Straits of Malacca or the Suez Canal, areas with a heavy U.S. naval presence.

Chinese actions in the Arctic are consistent with these goals. They are investing heavily in Russia’s natural gas fields in the Yamal Peninsula, mining in Greenland, and real estate, alternative energy and fisheries in Iceland. They are building icebreakers and ice-hardened ships to ply Arctic waters. And they are asserting themselves into international debates over Arctic governance, most recently by calling themselves a “near-Arctic” state.

Russia’s status as a great power is largely contingent on what they do in the Arctic. Their economy is heavily dependent on exporting oil and gas, much of which comes from their Arctic territory. Their fleet of nuclear-armed submarines is based in Murmansk, above the Arctic Circle. And they see the Northern Sea Route (NSR), a shipping channel along the Siberian coast, as a potential revenue source as well as an area that needs to be protected from oil spills and controlled from a military security perspective.

Russian actions in the Arctic arguably are consistent with these interests. They developed the Yamal natural gas fields with Chinese assistance. They refurbished or created military bases near Murmansk and along the NSR, and deployed what they claim are defensive weapons and search and rescue capabilities to those bases.

The combined Arctic moves of Russia and China have raised alarm bells in Washington, which fears its old Cold War enemies are planning to exercise territorial ambitions in the far north. National Geographic notes that in 2016, China tried to buy an abandoned naval base in Greenland, sailed its first ice breaker through the Northwest Passage in 2017, and last year, published a white paper outlining its Arctic plans.

Recently US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned his fellow foreign ministers at a meeting of the Arctic Council – an inter-governmental discussion forum – that the Arctic is emerging as a new “Great Game” between the US, Russia and China (notice Canada is not included), or maybe even a renewed Cold War.

Pompeo called out Russia’s claim over international waters of the Northern Sea Route and its moves to re-open military bases along the route as commercial shipping activity increases. And he disparaged China for even claiming to have a say in Arctic policy, noting that “the shortest distance between China and the Arctic is 900 miles.”

“Beijing claims to be a near-Arctic state,” Pompeo said, referring to China’s 2018 white paper on the Arctic. “There are Arctic states and non-Arctic states. No third category exists. China claiming otherwise entitles them to exactly nothing.”

For critics who thought that Pompeo shouldn’t be using the Arctic Council to make pronouncements of a political or military nature, he had this to say:

“We’re entering a new age of strategic engagement in the Arctic, complete with new threats to Arctic interests and its real estate.”

And in keeping with the Trump administration’s pugilistic approach to Canada, Pompeo disputed Canada’s claim to the Northwest Passage as internal waters, arguing the waters should be considered international.

Canadian politicians are also concerned about the new northern power grab. CBC recently reported on a Liberal MP saying that Canada will have to “use it or lose it” if it wants to fend off challenges from Russia in the Arctic.

As Russia, China, and increasingly, the US flex their Arctic muscles, Canada is the 90-pound weakling in the gym – having instituted a five-year ban on offshore energy exploration.

Ice-free shipping

The opening of polar sea routes as a consequence of melting ice is a double-edged sword. On the one hand it presents a huge opportunity for polar nations to increase trade and to drastically cut transportation expenses. Yet increased commercial activity also heightens the possibility of conflict especially in an area where ownership to surface and undersea rights isn’t always clear.

Pompeo told his Arctic Council peers that new, ice-free sea lanes could become “21s century Suez and Panama Canals,” which would “potentially slash the time it takes to travel between Asia and the West by as much as 20 days.”

Indeed, a ship sailing from East Asia to Western Europe through the Northwest Passage, instead of having to go through the Panama Canal, could potentially cut 10,000 kilometers from the voyage. Imagine how much fuel that would save shipping companies, and crewing costs, plus the opportunity to deploy more vessels more frequently.

Melting sea ice is already opening up the Arctic Ocean. In the summer of 2012, Ship Technology notes that 46 vessels with icebreaker escorts crossed the Northern Sea Route running from Murmansk, near Russia’s border with Norway, to the Bering Strait near Alaska. Climate scientists at UCLA in California, studying the impact of rising temperatures on shipping, found that by mid-century, ships will be able to travel the Northern Sea Route for three months during the summer without icebreakers.

Last summer a Danish freighter owned by Maersk became the first container ship to sail through the Northern Sea Route.

Resource treasure chest

At Ahead of the Herd we always follow the money to discover the reasons behind most decisions. It’s no exception with the Arctic, which contains a veritable treasure trove of natural resources – mostly oil and gas but some minerals too.

According to the US Geological Survey, the Arctic Circle (remember areas beyond the 200-nautical-mile economic exclusion zones are international ) contains up to 30% of the world’s undiscovered gas and 13% of its oil.

The Beaufort Sea off the coast of the Northwest Territories holds an estimated 56 trillion feet of natural gas and 8 billion barrels of oil.

There hasn’t been much in the way of offshore oil exploration in the Arctic since oil prices sunk in 2014 – the expense and high technology involved means such operations require high crude oil prices to be profitable.

For example, despite pouring billions into Arctic oil exploration, Shell has relinquished most of its federal offshore leases in Alaska’s Chukchi Sea. As oil prices have lifted, however, there is renewed interest. In 2017 US President Trump reversed restrictions on Arctic oil exploration passed during the Obama administration; the country is now encouraging companies to consider returning with offfshore drill rigs.

While the United States and Canada have pulled back on Arctic oil and gas extraction, Russia has gone in full-bore. Here’s Wired describing Russia’s impressive Yamal LNG project:

What better place to do that than Yamal—literally “end of the world” in the local Nenets language? The autonomous district is bigger than Texas and has 32 natural gas fields, with an estimated 35 trillion cubic yards of the stuff, according to Russian state oil company Gazprom. It’s here, on thousands of piles wedged deep into the permafrost, that US-sanctioned company Novatek just erected its $27 billion Yamal LNG (liquefied natural gas) plant. Bankrolled by the Chinese government and French gas giant Total, the plant extracts natural gas thousands of feet below ground and cools it to a liquid form that’s easier to transport. At full capacity, it can deliver up to 18 million tons of LNG a year to tankers sailing the Northeast Passage, bound for Europe and the US. “Putin has vowed to make Russia the leading LNG exporter,” Grigas says. “Yamal LNG represents that ambition.”

Among the non-energy minerals hidden within the Arctic’s barren lands are coal, diamonds, uranium, phosphate, nickel and platinum group elements (PGE). Rare earth elements and cobalt needed for electric vehicles have also been found in the Arctic regions of Russia and Scandinavia.

Global News notes that Greenland, an autonomous region of Denmark, is claiming the Lomonosov Ridge – an underwater feature extending hundreds of miles beneath the Arctic Sea – for future undersea mining – although Russia disagrees.

Conclusion

In this article we have only just touched on the many issues the Arctic represents. As global warming continues to melt glaciers and sea ice, exposing vast expanses of ocean water to sunlight, more and more of the Arctic will become navigable for international shipping and resource exploration.

Up to now considered to be too difficult and expensive a place to work, in the near future the Arctic is likely to become less daunting, as temperatures rise and ice and snow cover retreat.

With opportunity however comes risk.

The eight countries that touch the Arctic Circle and one that doesn’t (China) may be friendly to each other now but as new resources are identified, expect there to be conflicts and confrontations.

Russia, China and the United States are on track in beefing up their military and civilian presence in the Arctic. Unfortunately, the same can’t be said of Canada.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.