Lured by copper, major miners drawn to Quesnel Trough and Golden Triangle – Richard Mills

2024.04.24

The copper price tickled $4.55 a pound on Monday or $10,000 a tonne, setting a new two-year high, as investors continue to wager that miners will struggle to produce enough red metal to meet demand.

Bloomberg noted base metals have posted broad gains in recent weeks, due to signs of improved manufacturing activity, including in the two largest economies, the US and China.

Global manufacturing recovery underway, can it last? — Richard Mills

Copper market

The main reason copper has been climbing is due to tighter supply as demand steadily increases — something we at AOTH have been pounding the table about for years. In fact we were the first resource investing newsletter to identify the coming supply deficit, which wasn’t supposed to happen until 2025 but is already here.

While some dismissed our warnings, others are now acknowledging we were right. Part of the reason for the price surge are sliding stocks in LME registered warehouses, which at 121,200 tonnes have dropped more than 35% since October, Reuters said.

The other reason is less mine supply coming to market.

Production concerns began last year, when the government of Panama ordered First Quantum Minerals to shut down its Cobre Panama operation, removing nearly 350,000 tonnes from global supply.

A strike at another large copper mine, Las Bambas in Peru, temporarily halted shipments. Copper specialist Anglo American says it is scaling back output by about 200,000 tons, owing to head grade declines and logistical issues at its Los Bronces mine.

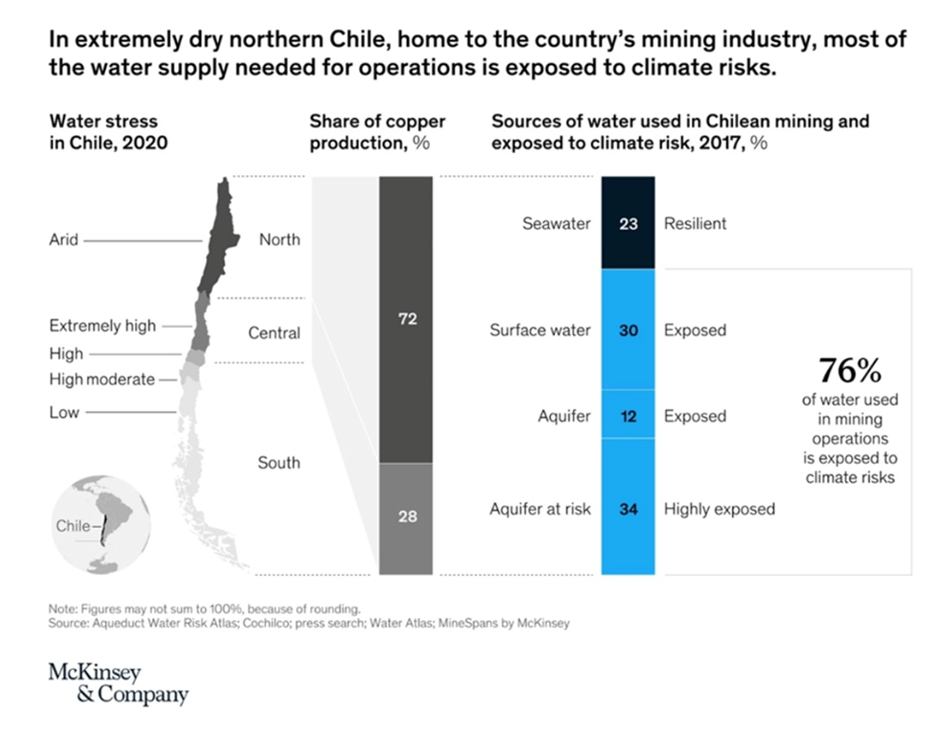

Chile’s copper output has been dented by a long-running drought in the country’s arid north. State miner Codelco’s 2023 production was the lowest in 25 years.

All four of Codelco’s megaprojects have been delayed by years, faced cost overruns totaling billions, and suffered accidents and operational problems while failing to deliver the promised boost in production, according to the company’s own projections.

There are also concerns about Zambia, Africa’s second largest copper producer, where drought conditions have lowered dam levels, creating a power crisis that threatens the country’s planned copper expansion.

Finally, Ivanhoe Mines reported a 6.5% quarterly drop in production at the world’s newest major copper mine, Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC.

All these supply interruptions have left Chinese copper smelters paying steep prices for mined ore, leading them to a rare agreement to jointly cut production in response.

In a nutshell, there are too many smelters and not enough imported raw copper ore to feed them.

Goldman Sachs, via Oilprice.com, has said it predicts a deficit of over half a million tonnes in 2024 due to mining disruptions. “The supply cuts reinforce our view that the copper market is entering a period of much clearer tightening,” analysts at the bank wrote.

Some of the world’s largest mining companies, market analysis firms and banks are warning that by mid-decade, a massive shortfall will emerge for copper, which is now the world’s most critical metal due to its essential role in the green economy.

(On July 31, 2023, the US Department of Energy officially put copper on its critical materials list, marking the first time a US government agency has included copper on such a list, following the examples set by the EU, China, Canada, and other major economies.)

The deficit will be so large, The Financial Post stated, that it could hold back global growth, stoke inflation by raising manufacturing costs, and throw global climate goals off course.

To achieve net-zero emissions targets, annual copper demand is likely to double to 50 million tonnes (Mt) by 2035, according to a study by S&P Global. In 2023, mines only produced 22Mt globally.

Simply put, electrification doesn’t happen without copper, the heartbeat of the global energy economy.

Along with the usual applications in construction wiring and plumbing, transportation, power transmission and communications, there is now added demand for copper in electric vehicles, EV charging stations, and renewable energy systems.

Commodity trader Trafigura recently told Reuters that Flourishing activity in the electric vehicle, power infrastructure, AI and automation sectors will lead to at least 10 million metric tons of additional copper consumption over the next decade… one third of the 10 million tons of new demand would come from the electric vehicle sector.

The US Geological Survey estimates that, while the world has produced 700 million tonnes of copper, there are 2.1 billion tonnes worth of discovered copper deposits yet to be tapped.

Two reasons we aren’t extracting more copper are costs (incentive pricing in the copper industry is considered to be anywhere from US$11,000/t to 15,000/t) and regulatory delays.

In North America, it can take up to 20 years for a mine to go from discovery to production.

Porphyries

The mining industry is on the hunt for large copper deposits that have favorable grades and are in locations amenable to mine developments.

Over 80% of the world’s copper production comes from large-scale open-pit porphyry copper mines.

According to a journal article titled ‘Gold in porphyry copper deposits: its abundance and fate’, Porphyry copper deposits are among the largest reservoirs of gold in the upper crust and are important potential sources for gold in lower temperature epithermal deposits…

Gold is found in porphyry copper deposits in solid solution in Cu–Fe and Cu sulfides and as small grains of native gold, usually along boundaries of bornite… bornite and chalcopyrite can contain about 1000 ppm gold at typical porphyry copper formation temperatures of 600–700°C, and indicate that bornite and chalcopyrite in porphyry copper deposits were saturated with respect to gold at temperatures of only 200–300°C.

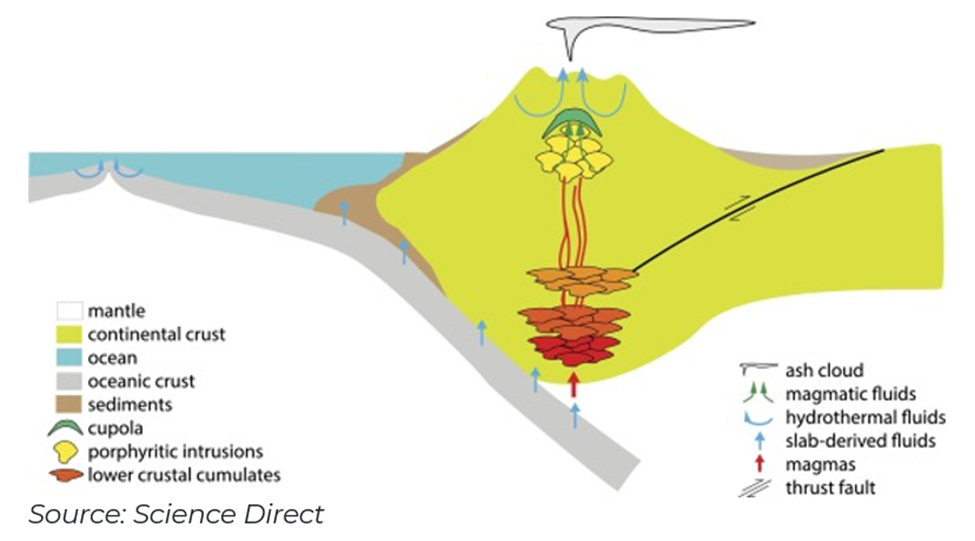

A porphyry deposit is formed when a block of molten-rock magma cools. The cooling leads to a separation of dissolved metals into distinct zones, resulting in rich deposits of copper, molybdenum, gold, tin, zinc and lead. A porphyry is defined as a large mass of mineralized igneous rock, consisting of large-grained crystals such as quartz and feldspar.

Porphyry deposits are usually low-grade but large and bulk mineable, making them attractive targets for mineral explorers. Porphyry orebodies typically contain between 0.4 and 1% copper, with smaller amounts of other metals such as gold, molybdenum and silver.

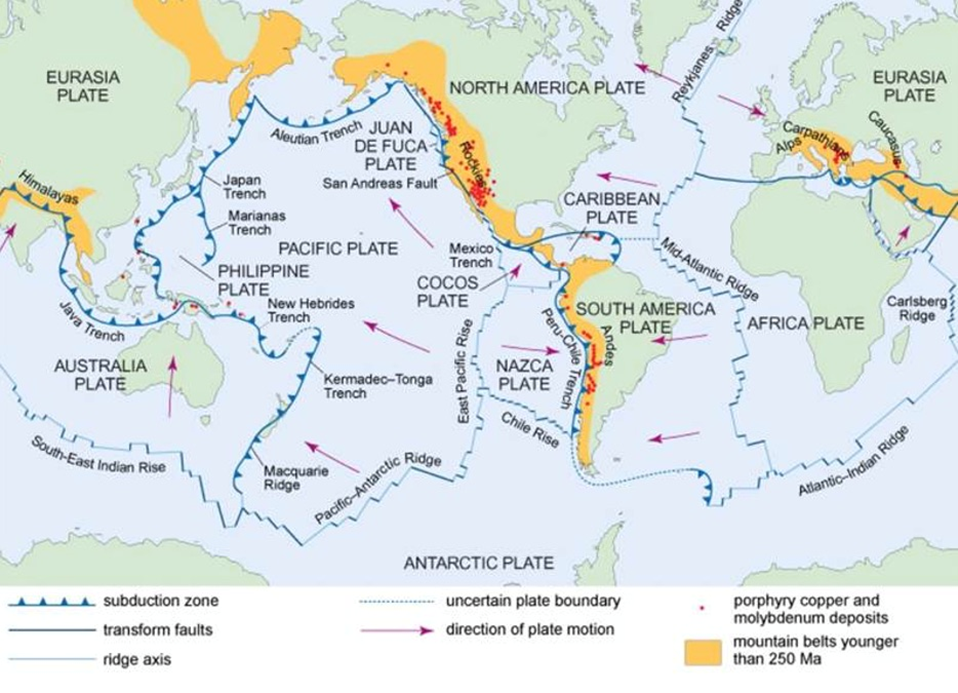

Most porphyry copper deposits occur close to subduction zones around the Ring of Fire — the horseshoe-shaped Pacific Ocean basin where regular and sometimes dangerous earthquakes and volcanic eruptions occur. The Ring of Fire stretches 40,000 kilometers from the southern tip of South America, up the North and South American coasts to the Aleutian Islands, down the East and Southeast coasts of Asia, and ending in a boomerang-shaped arc off the eastern coast of Australia.

Copper porphyries were the first metallic deposits to be mined in open pits, starting in 1905 with the Bingham Canyon mine in Utah. Since 1970 over 95% of US copper production has come from porphyry deposits, and more than 60% of world annual copper production.

Among the largest copper porphyry mines are Chuquicamata (690 million tonnes grading 2.58% Cu), Escondida and El Salvador in Chile, Toquepala in Peru, Lavender Pit, Arizona and Malanjkhand, India, which has 145Mt at 1.35% Cu.

In Canada, British Columbia enjoys the lion’s share of porphyry copper/ gold mineralization. These deposits contain the largest resources of copper, significant molybdenum and 50% of the gold in the province.

Examples include big copper-gold and copper-molybdenum porphyries such as Red Chris and Highland Valley. Large, undeveloped porphyry deposits along the North American Ring of Fire include Galore Creek in BC and the Pebble project in Alaska.

There has been a definite trend by major mining companies towards making deals with junior resource companies that own copper/gold porphyry projects in BC. Historical examples include:

- Tiex/Newmont

- Novagold/Teck Resources

- Cariboo Rose/Gold Fields

- Terrane Metals/Goldcorp

- Kiska Metals (formerly Rimfire Metals)/Xstrata

- Serengeti/Freeport

- Strongbow/Xstrata

- Copper Mountain/Mitsubishi

In the table below by GlobalData, via Mining Technology, we note that of 10 major operating copper mines in Canada, six are in BC.

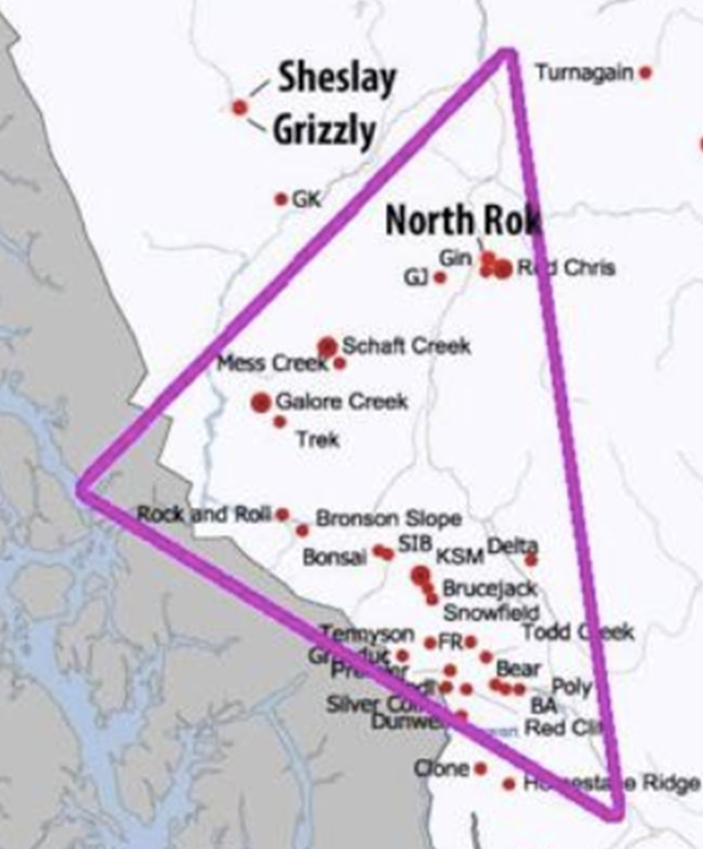

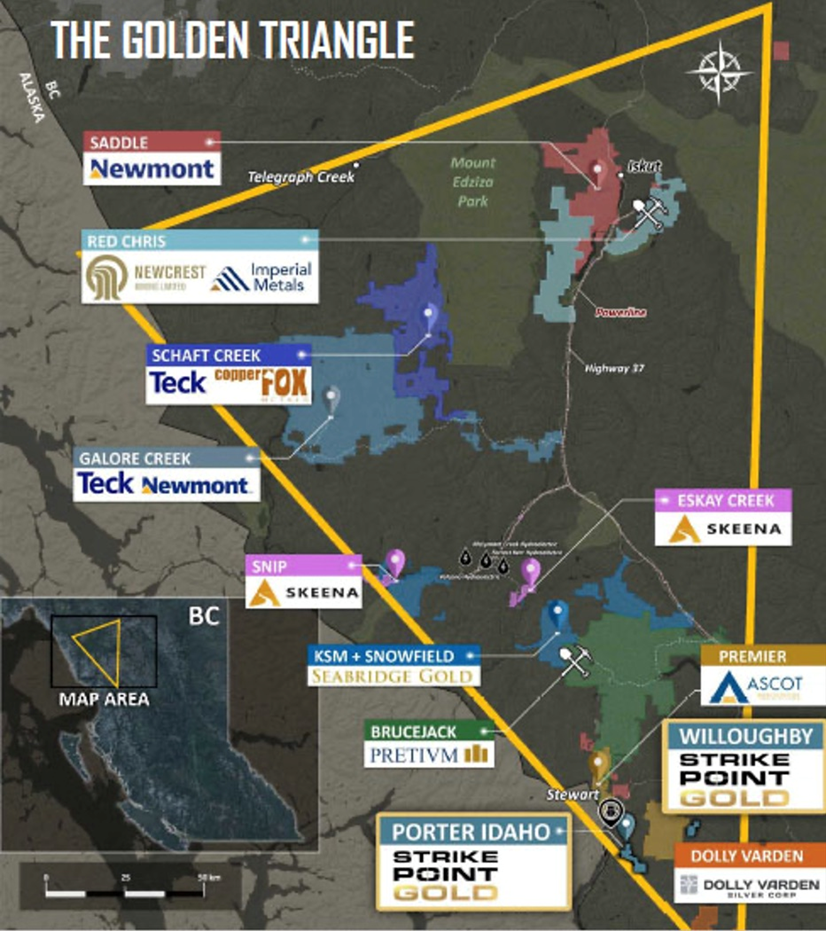

The Golden Triangle

The Golden Triangle of northwestern British Columbia is an excellent place to shore up new copper supply and to build smelting and refining capacity. The GT is one of the most richly mineralized areas on the planet, hosting large deposits of copper, gold and silver. Of the triangle’s two operating mines and one to come, Brucejack has proven and probable reserves of 14.4 million tonnes @ 8.3 grams per tonne gold and 63.8 g/t silver, Red Chris contains 410Mt @ 0.45% Cu (2.02Mt) and 0.55 g/t Au (7.78Moz), while the Premier gold project has an indicated resource of 1.066Moz Au and 4.669Moz of silver.

Ascot Resources poured first gold at Premier in April 2024. Several undeveloped deposits reinforce the enormous potential of the region.

Major porphyry camps and porphyry-related gold deposits within the Golden Triangle include Schaft Creek, Galore Creek, the Red Chris-GJ-North Rok-Tatogga cluster and the KSM-Brucejack-Treaty camps.

Most of British Columbia is made up of blocks of Earth’s crust (terranes) that became attached to the coast over hundreds of millions of years. These terranes include a wide variety of rock types, including metal-rich material derived from the depths of the crust.

Most metal deposits are derived from hydrothermal systems. That is, superheated water, circulating kilometers deep in the crust, gathers metal atoms and then deposits them in particular zones, creating concentrations of metals. Typically, such a system would remain active for hundreds of thousands of years to as much as perhaps a couple of million years. For reasons not yet well understood, the hydrothermal processes in the Golden Triangle were active for much longer, in some areas for perhaps 10 million years. Few areas on the planet have seen such long-lived geological conditions.

That long period of stable mineralizing systems played an important role in creating the high concentrations of metals at Eskay Creek — once the world’s highest-grade gold mine — and Valley of the Kings, developed by Pretium Resources into the Brucejack mine. It is also the reason for the very large and well-mineralized systems at Red Chris, KSM, Galore Creek and other porphyry deposits in the region.

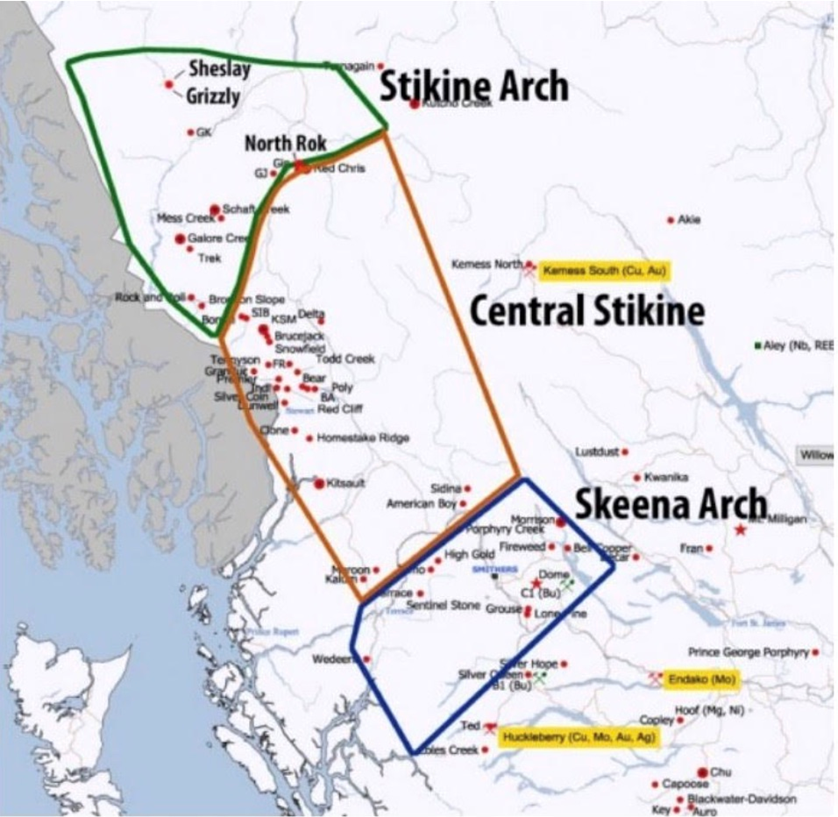

About 150 million years ago during the Jurassic geological period, an uplift of Jurassic and older rocks cut across central British Columbia and resulted in the separation of the Bowser and Nechako basins. Rocks exposed along the “Skeena Arch” represent a magmatic arc, where over a long period of time, magma rose up to produce a wide range of mineral deposits including porphyries, precious metal veins and coal. The Skeena Arch has some of the mostly richly endowed mineral terrain in BC and has been a destination for prospectors and mining companies for the past 125 years.

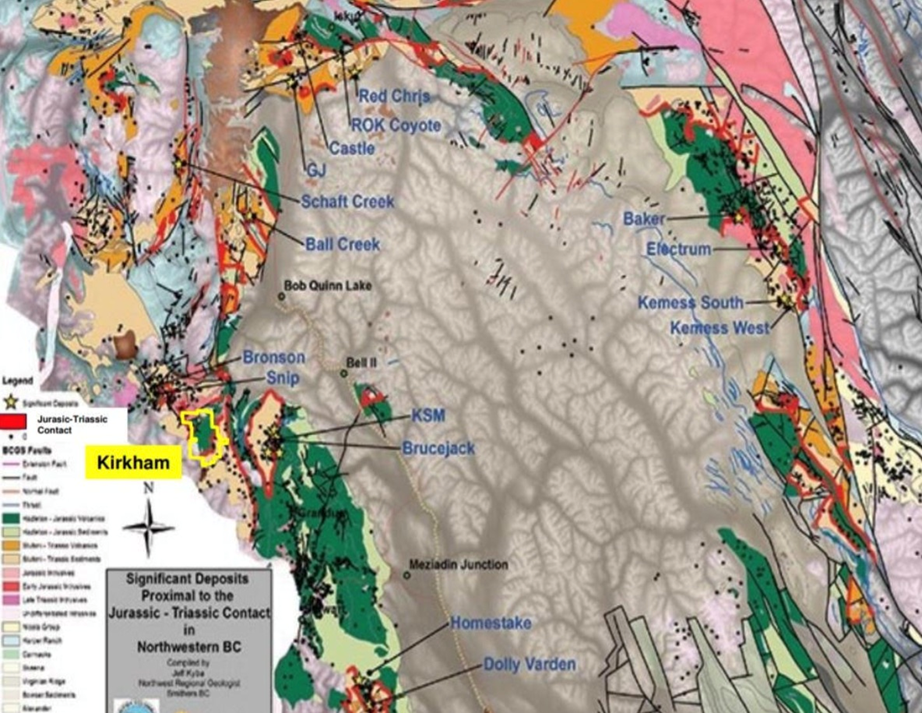

Note the three arches bounding the Golden Triangle in the second map: the Skeena Arch, Central Stikine and Stikine Arch. The Stikine Arch is one of four terranes – or distinct geological structures with different histories – along with Cache Creek, Yukon-Tanana and Cassiar, which form the bedrock of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province, a wide belt of volcanoes that extends all the way from Stewart, BC in the south, through the Alaska Panhandle north to eastern Alaska.

According to a presentation by Geoscience BC, “World class gold-rich deposits are associated with the Late Triassic, and Early Jurassic intrusive suites in NW Stikinia.” The non-profit research group also states that bulk tonnage copper/ gold/ silver porphyries (igneous rock consisting of large-grained crystals such as feldspar or quartz) in the Stikinia, and bonanza-grade gold and silver epithermal veins are associated with the early Jurassic period, such as the KSM, Snowfield and Brucejack deposits.

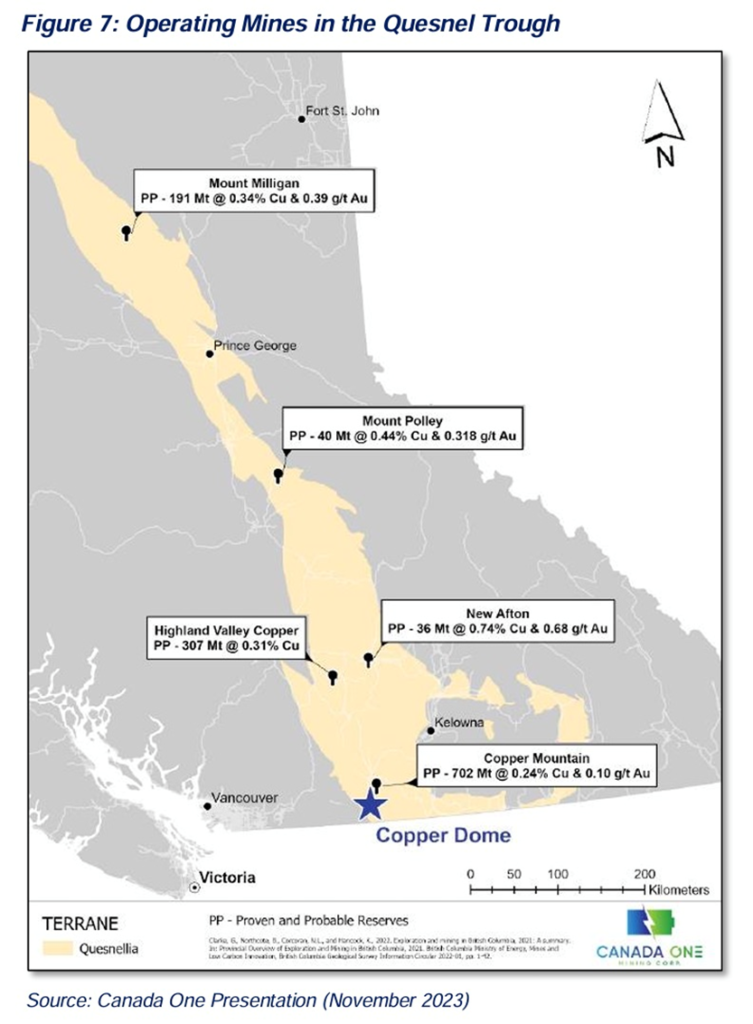

The Quesnel Trough, also called the Quesnel Terrane, is a Triassic‐Jurassic aged arc of volcano sedimentary rocks that hosts several alkalic copper-gold porphyry deposits. Operating mines include Mount Milligan, Mount Polley, New Afton, Highland Valley and Copper Mountain.

According to the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC),

The Quesnel Terrane, along with the Stikine Terrane, are two Mesozoic-age volcanic arcs preserved in western Canada. These parallel arc terranes extend for 2,000 km along the axis of the Canadian Cordillera. They are joined at their northern ends, but are otherwise separated by relics ofTethyan ocean basin and oceanic arc rocks collectively referred to as the Cache Creek Terrane. Porphyry Cu ± Au‐Mo Ag deposits are concentrated within the Stikine‐Quesnel arc terranes.

More than 90% of the known copper endowment was emplaced within a 6 million-year pulse centered on 205 Ma. Distinct trends of Cu‐Au ± Ag Mo mineralization within both arc terranes coincide in time and space with events that are attributed to effects of slab subduction.

The Quesnel Trough extends over 1,000 kilometers from Washington State to the Yukon border. It is the longest mineral belt in Canada.

David Moore, the former president of Serengeti Resources (now NorthWest Copper) developing the Kwanika-Stardust project, told Resource World magazine, “The Quesnel Trough is of paramount importance to the British Columbia mining sector with its rich mineral endowment, for copper and gold in particular. These copper-gold porphyries include Copper Mountain, New Afton, Mount Milligan, Woodjam, Kwanika and Kemess, to name a few. Teck’s huge Highland Valley Mine is, of course, very important to Canada.”

Moore noted the various deposit types along the Quesnel Trough.

“There are copper-gold deposits such as Copper Mountain, copper-molybdenum deposits such as Highland Valley, as well as deposits with gold and a little copper, copper-molybdenum deposits, as well as copper-moly-silver with a lower gold type of deposits,” he said. “There are also copper and gold skarn deposits.”

Red Line

While the geology of the Golden Triangle has been well known for decades, it took a new twist to get geologists back into the field. Jeff Kyba, a former geo with the BC government, theorized that geologic contact between Triassic-age Stuhini rocks and Jurassic-age Hazelton rocks is the key marker for copper-gold mineralization. That means most of the Golden Triangle’s deposits are found within 2 kilometers of this contact zone, which Kyba and his team dubbed “The Red Line”. His theory, published in a BC government paper, was significant because it was the first time anyone had tied the area’s discoveries together with a structural explanation.

In a 2015 article in The Northern Miner, Kyba said,

“The contact represents a period in Earth’s history when a lot of deposits in BC were forming. But no one really knows what controlled their emplacement and where best to look. We’re trying to answer that question, and so far the results are exciting.”

Between 220 and 175 million years ago, subduction and volcanism along the above-mentioned Stikine Terrane, an ancient volcanic arc, promoted the emplacement of world-class deposits such as KSM, Brucejack, Eskay Creek, Schaft Creek and Red Chris.

But according to the article,

[D]uring the Cretaceous period, starting 144 million years ago, the metal-rich arc was compressed to nearly half its length as the margin of western North America collided with other terranes. The deformation was so intense that it obliterated most structural clues related to the main mineralizing event, making it difficult for explorers to locate the deposits, the article reads.

“The rocks here are much older than those in the Philippines or Indonesia, so they’ve been banged up quite a bit,” he says. “But just because the geology is more complex, doesn’t mean the deposits aren’t there.”

“Over the past five years, the northwest Stikine has built its momentum towards becoming the world’s next big mineral province,” he says. “People are recognizing that these deposits have high-grade roots and big extensions they never thought were there.” Kyba and Nelson started their investigations at the KSM and Brucejack copper-gold camp, where Pretium geologists were finding evidence for an old tectonic event that influenced mineralization.

What they found was a unique package of basal conglomerates and turbidites along the Stuhini-Hazelton group stratigraphic contact. “To a geologist, these rocks indicate a hiatus in ancient volcanism and an increase in earthquake activity,” he explains. “The land was uplifted along faults, and near its edges, the rocks were eroded and deposited into the basin below.” Kyba believes this tectonism provided the framework for metal-rich fluids and intrusions to migrate along when volcanism resumed during Hazelton time…Kyba mentions he has an “open-door” policy on the data he uses, and offers explorers a geological map that highlights the prospective contact as a thick, red line.“If you’re near that red line, and there’s a clastic sequence coupled with large-scale faults, then you might be in the neighbourhood of B.C.’s next big deposit,” he says. “And knowing that is a big game changer for explorers in the region, because it’ll get them closer to making a discovery.”

Major and mid-tier miners in the GT

Major and mid-tier mining companies have been sniffing around the Golden Triangle and its estimated $4 trillion worth of metals for decades, but in the past few years the motivation has changed from high-grade gold to copper, which, as argued at the top, has become a critical metal essential to the green energy and electrification shift.

Copper-gold porphyries offer majors/ mid-tiers the scale and longevity of mine life needed to replace their dwindling reserves.

Newmont

A great example of this trend is US gold miner Newmont. At the recent BMO Global Metals, Mining & Critical Minerals Conference 2024 in Hollywood, Florida, CEO Tom Palmer shared his vision for the company.

Its value proposition revolves around three areas: the ability to further strengthen Newmont’s portfolio with Tier 1 acquisitions, the opportunity to consolidate assets to three jurisdictionally safe countries, and exposure to copper.

(A Tier 1 gold asset has the reserve potential to deliver a minimum 10-year life, annual production of at least 500,000 ounces, and cash costs over the mine life that are in the lower half of the industry cost curve.)

“In announcing our go-forward portfolio, it’s exclusively Tier 1. Those operations are either Tier 1 today, or they have a pathway to get to Tier 1, and a key part of that go-forward portfolio is British Columbia. It’s a Tier 1 district that we’ll be operating in for the next century,” said Palmer, referring to the Golden Triangle.

Regarding Newmont’s copper exposure, Palmer said:

“A significant proportion of the metal that we’ll produce out of British Columbia will be copper from the Red Chris block cave, it’ll be copper from Galore Creek, our partnership with Teck [Resources], and we’ll have a nice amount of gold from Brucejack as well as Red Chris and Galore Creek… a fabulous district to be in.”

Newmont inherited Newcrest’s 70% ownership of the Red Chris mine when it acquired the Australian gold major last year. Imperial Metals owns the other 30%. The open-pit copper-gold project has an underground block cave currently being developed to take it up to Tier-1 scale. The mine produced 18,000 tonnes of copper and 39,000 ounces of gold in 2023. Proven and probable reserves as of June 30, 2023, were 410Mt at 0.45% Cu (2.02Mt) and 0.55 g/t Au (7.78Moz).

Through the mega-merger, Newmont also gained 100% ownership of the high-grade Brucejack gold mine, wedged between two glaciers and operating since 2017. Mine developer Pretium Resources sold the operation to Newcrest in 2022. It produced 286,000 ounces of gold in 2023, according to Newmont.

In 2021, Newmont paid USD$311 million for GT Gold, which had a large porphyry-gold deposit on its Tatogga property in the Golden Triangle.

According to Mining News North

Newmont first grabbed a solid foothold in the Golden Triangle with the 2018 acquisition of Novagold Resources’ 50% interest in Galore Creek, a large copper-gold-silver project it now owns in partnership with Teck Resources Ltd.

Shortly after the Galore Creek acquisition, Newmont invested CAD$17.6 million to acquire an initial stake in GT Gold.

This interest in Tatogga came on the heels of GT Gold’s discovery of Saddle North, a porphyry copper-gold deposit similar to those at [Newmont’s] and Imperial Metals’ Red Chris mine about 20 kilometers to the southeast.

Barrick Gold

Barrick Gold, now the third-largest gold company by market capitalization behind Newmont and Agnico Eagle Mines, previously owned Eskay Creek, a volcanogenic massive sulfide (VMS) deposit with some of the highest gold and silver grades in the world.

Within its 14-year life, Eskay Creek produced 3.3 million ounces of gold at an average grade of 45 grams per tonne, and roughly 160Moz silver at around 2,220 g/t — making it the world’s highest-grade gold mine and fifth-largest silver mine by volume.

In 2020 Barrick inked a deal with junior Skeena Resources after concluding an agreement three years earlier that would allow Skeena to acquire 100% ownership of the former underground mine.

The same year, Skeena acquired 100% ownership of the past-producing Snip mine from Barrick. Snip produced about 1 million ounces of gold from 1991 to 1999 at an average grade of 27.5 g/t Au.

As Newmont expands its land position in the Golden Triangle through acquisitions, rival Barrick appears to be moving out of the region, and Canada.

The Financial Post noted that, following the ownership change of the Brucejack mine from Newcrest to Newmont, it left Barrick with only one operating mine in Canada — Hemlo in Ontario, whose production has fallen steeply in recent years.

Teck Resources

Teck is an important player in the Golden Triangle with two assets — one producing and one under development.

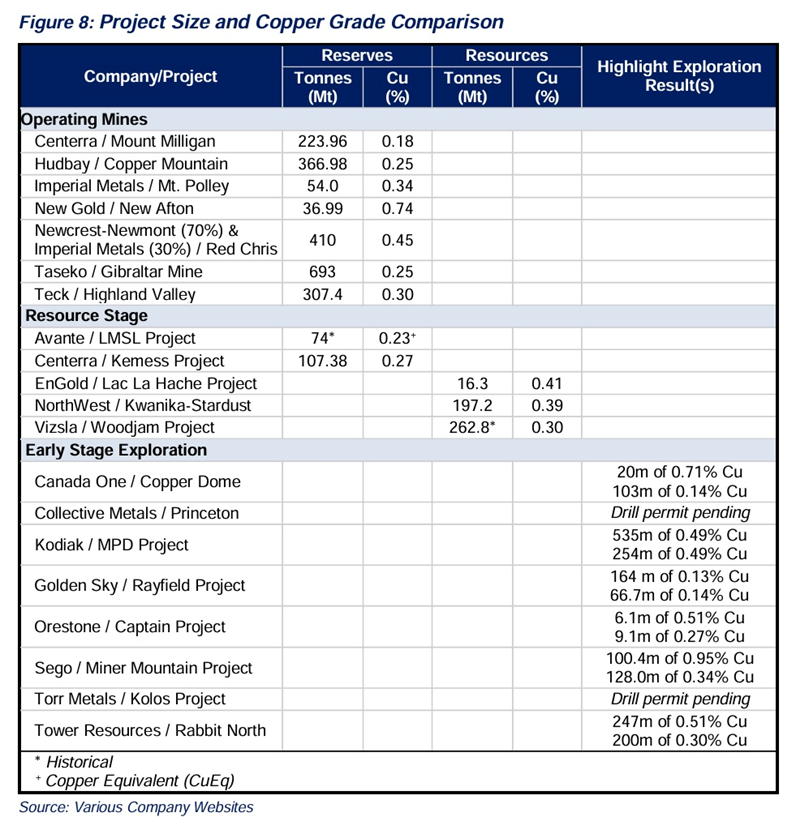

The Highland Valley copper mine, located about 50 km from Kamloops in southcentral BC, produces copper and molybdenum concentrates. A hundred percent owned by Teck, Highland Valley is the largest copper mine in Canada.

The HVC Mine Life Extension Project would yield nearly 2 million tonnes of additional copper over the life of the project.

According to a press release, the company’s 296,500 tonnes of copper production last year included 98,800 tonnes from Highland Valley.

It is expected to produce between 110,000 and 118,000 tonnes of Cu in 2023 and 120,000 to 165,000 tonnes of Cu in 2024. The current mine life extends to 2028 with exploration plans to prolong the mine life to 2040. As of Dec. 31, 2022, the copper-molybdenum deposit has proven and probable reserves of 307.4Mt grading 0.30% Cu (790Kt) and 0.008% molybdenum (10Kt). (eResearch Industry Report, Feb. 29, 2024)

Teck has other metal mines in Peru, Chile, Alaska and Minnesota, along with a smelter in Trail, southeastern British Columbia.

The Galore Creek Mining Corporation is a 50-50 partnership between Newmont and Teck. Newmont last year announced it achieved 50% ownership by making a series of payments totaling USD$275 million in the copper-gold project.

GCMC says the 2024 field program will include approximately 6,000 meters of geotechnical, metallurgical, and resource development drilling, along with geotechnical and geophysical surveys.

The Schaft Creek Joint Venture between Teck (75%) and Copper Fox Metals (25%) was formed in 2013. The project has reached the preliminary economic assessment (PEA) stage and has a mineral resource estimate. The PEA envisions a 21-year mine producing about 5 billion pounds of copper, 3.7 million ounces of gold, 226Mlbs molybdenum and 16.4Moz silver in concentrate. The resource estimate shows 7.767 billion pounds of copper in the measured and indicated categories, 6.97Moz of gold, 54.25Moz of silver, and 511Mlbs of molybdenum.

Imperial Metals

Imperial Metals owns or partly owns three mines in British Columbia: (above-mentioned) Red Chris, Mount Polley and Huckleberry.

Located 56 km northeast of Williams Lake, Mount Polley resumed operations in 2022 after a three-year closure following a tailings dam breach.

The open-pit mine produced 30.1 million pounds of copper and 41,834 ounces of gold in 2023. Proven and probable reserves at the end of 2022 were 54Mt at 0.34% Cu (403 Mlbs), 0.32 g/t Au (0.55Moz), and 0.90 g/t Ag (1.54Moz).

The Huckleberry mine is currently on care and maintenance.

In 2021, Imperial Metals acquired a 30% interest in the GJ property for $3.04 million from its joint-venture partner Newcrest Red Chris Mining Limited. According to a press release, GJ has known copper-gold porphyry mineralization and is located approximately 30 kilometers southwest of the Red Chris mine.

Hudbay Minerals

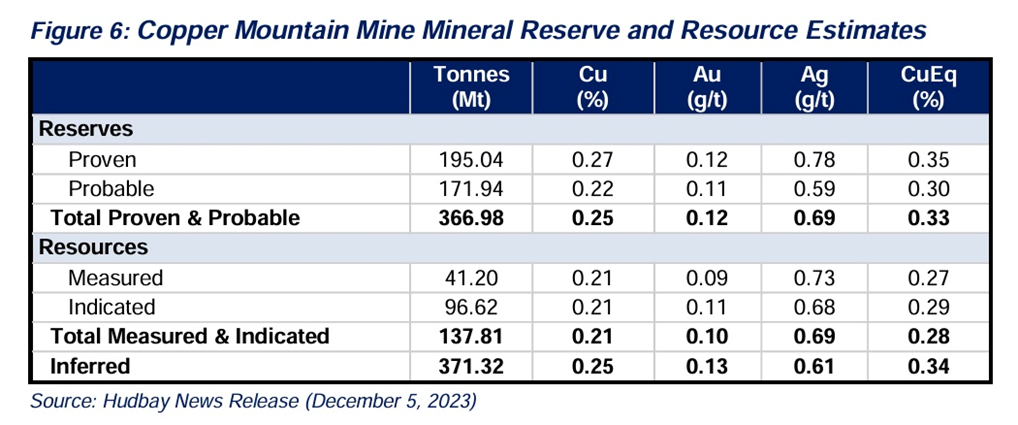

Last year Hudbay Minerals paid US$663 million for a 75% stake in the Copper Mountain mine located near Princeton in southwestern BC. The other 25% is owned by Mitsubishi Materials. The copper-gold-silver mine is expected to produce approximately 45,000 tonnes of copper and 49,500 ounces of gold annually over the next 10 years, with a 21-year mine life and total production of 783,000 tonnes of copper, 0.9 million gold ounces, and 5.6 million silver ounces.

As of Dec. 1, 2023, proven and probable reserves were 367Mt at 0.25% Cu, 0.12 g/t Au, and 0.69 g/t Ag, with a copper-equivalent grade of 0.33%. (eResearch Industry Report, Feb. 29. 2024)

Centerra Gold

Centerra Gold’s Mount Milligan Mine, located 156 km northwest of Prince George, has proven and probable reserves (Dec. 31, 2022) of 223.96Mt at 0.18% Cu (900Mlbs) and 0.37% Au (2.6Moz).

According to the company, 2023 production was 62 million pounds of copper and 154,000 ounces of gold.

Taseko Mines

Taseko owns 87.5% of the Gibraltar mine located 65 km north of Williams Lake in central BC. The open-pit copper-moly mine is the second-largest open pit copper mine in Canada and the fourth-largest in North America. It is expected to operate until 2044.

In 2023, the mine produced 123Mlbs pounds of Cu and 1.2Mlbs of molybdenum (Mo). As of Dec. 31, 2022, total proven and probable Reserves were 693Mt at 0.25% Cu and 0.008% Mo. (eResearch Industry Report, Feb. 29. 2024)

New Gold

New Gold owns and operates New Afton, an underground copper-gold mine located near Kamloops in southcentral BC.

It is the only operating block cave mine in Canada.

2023 production was 47.4 million pounds of copper and 67,433 ounces of gold.

As of Dec. 31, 2022, proven and probable reserves were 36.99Mt at 0.74% Cu (607Mlbs), 0.68 g/t Au (0.80Moz), and 1.7 g/t Ag (2.0Moz).

New Gold announced the completion of a new life of mine plan in March 2020 that incorporated the C-Zone development. It extends the mine life to at least 2030. (eResearch Industry Report, Feb. 29. 2024)

Hecla Mining

The largest silver producer in the United States now has more skin in the game at Dolly Varden Silver’s Kitsault Valley project, located on the southern end of the Golden Triangle.

Last fall, Dolly announced that Hecla will purchase 15,384,616 shares at $0.65 per share for gross proceeds of $10 million. Hecla’s share percentage increased from 10.6% to 15.7%, calculated on an undiluted basis.

Hecla already had a presence in the area through its Kinskuch property, which the company says hosts potential for silver-gold, gold-rich porphyry, and VMS deposits.

When Dolly Varden purchased the Big Bulk copper-gold porphyry property from Libero in December 2023, the press release notes that Big Buk is surrounded by Kinskuch. According to Dolly,

The Big Bulk porphyry copper-gold system hosts multiple phases of intrusive rocks, hosted in Lower Jurassic-age Hazelton and Triassic-age Stuhini volcanic and sedimentary rocks. Recent work by the British Columbia Geological Survey (“BCGS”) and University of British Columbia (“UBC”) Mineral Deposits Research Unit (“MDRU”) indicate that Big Bulk is the northernmost porphyry of a string of several porphyry mineralized systems of multiple geologic ages that extend 30km south to the New Moly LLC’s Eocene-age Kitsault molybdenum deposit.

Coeur Mining

Another American precious metals producer, Coeur Mining, is active in the Golden Triangle with its Silvertip silver-zinc-lead exploration project. Located 16 km south of the BC-Yukon border, Coeur says Silvertip is one of the highest-grade Ag-Zn-Pb project in the world; 2023 measured and indicated resources were 57.7 million ounces of silver, 1.5 billion pounds of zinc and 768.7 million pounds of lead.

Coeur acquired the mine and mill in 2017 but ceased operations in 2020 after spending CAD$100 million at the site. The company is reportedly raising $25 million via flowthrough shares to continue exploration.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Richard does not own shares of any company mentioned in the article.

Dolly Varden is a paid advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.