Is the US willing to give up the world’s reserve currency to fix its trade deficit?

2021.10.15

The balance of trade is an important barometer of a country’s economic health. A trade deficit occurs when the value of its imports exceeds the value of its exports, with imports and exports referring to both goods and services.

A trade deficit simply means a country is buying more goods and services than it is selling. This situation generally hurts job creation and economic growth, although it is good for consumers who are able to buy cheap imports due to the deficit-running country’s currency being stronger than its trading partners.

The widening trade gap especially with China was a prominent theme in the 2016 US presidential election, and a primary reason that the former US president launched a trade war soon after taking office. Trump thought that cutting the trade deficit by slapping tariffs on goods imported from China, mostly, along with the EU and Canada, would bring back US jobs lost to out-sourcing, and strengthen the economy.

It didn’t work.

The online magazine ‘Reason’ quotes Scott Lincicome at the Cato Institute stating “The tariffs that the Trump administration imposed on Chinese imports harmed U.S. consumers and manufacturers, deterred investment (mainly due to uncertainty), lowered U.S. GDP growth, and hurt U.S. exporters (especially farmers but also U.S. manufacturers that used Chinese inputs).”

Despite this, the tariffs remain and will likely be increased. In an end of September interview with Politico, US Trade Representative Katherine Tai said that the Biden administration plans to build on existing tariffs on many more billions of dollars in Chinese imports and confront Beijing for failing to fulfill its obligations under a Trump-brokered trade agreement.

Indeed the administration appears more focused on cultivating ties with other countries to present a united front against China, than returning to a (mostly) tariff-free arrangement with its largest trading partner.

Meanwhile, writes Reason, While tariffs are pitched to the public as a way to help domestic workers or boost U.S. competitiveness, they always penalize domestic consumers through fewer choices and higher prices.

As for the US trade deficit, is has gone up since Trump left office in January 2021. CNBC reported the deficit hitting a record-high $73.3 billion in August, boosted by imports as businesses rebuilt inventories drawn down during the pandemic.

Goods imports rose 1.1% to $239.1 billion, led by consumer items such as pharmaceuticals, toys, games and sporting goods. Imports of services increased $1.3 billion to $47.9 billion in August. Overall, imports shot up 1.4% to $287B, the highest on record, CNBC said.

Forbes chipped in that the annual trade gap is on track to top $1 trillion for the first time, suggesting that Trump’s tariffs on China and Europe have had a limited impact on slowing US imports.

The article, by subject expert Ken Roberts, notes that Vietnam is a big part of the reason for the deficit increasing. America’s trade gap with its former Cold War adversary through June topped $42 billion, third behind China and Mexico. For every dollar of US-Vietnam trade, only 11 cents is a US export.

The other reason is the unusual situation US consumers find themselves in. Prone more to spending than saving, a lot of Americans hunkered down during the pandemic, preferring to hold off on major purchases and pay down debt. Roberts explains:

There has been and still is a lot of money in the pockets of consumers and businesses, thanks to the largesse of the U. S. Congress and its efforts to stave off the ill effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economy, and to the Federal Reserve’s interest rate and other policies, with the same goals. Those efforts have succeeded, perhaps too well.

The economy continues to grow rapidly, though it is perhaps beginning to show signs of slowing, with demand outpacing the supply chain’s ability to keep up, leading to inflation.

The inflationary theme is one we at AOTH have picked up on and written a number of recent articles about.

The US Federal Reserve’s official line is that inflation is only temporary, however we see things differently.

In June the US consumer price index (CPI) surged by 5.4%, the most since 2008, as economic activity picked up but was constrained in some sectors by supply bottlenecks.

The pandemic has put tremendous pressure on supply chains, and the prices of many agricultural commodities such as grain, corn and soybeans, have skyrocketed, as shown in the food inflation chart above.

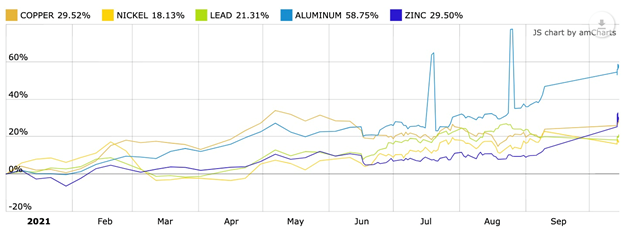

Several industrial metals have enjoyed significant price gains, too, including copper, nickel, zinc, lead and aluminum.

The US government is reportedly stepping up efforts to relieve the “supply chain nightmare” that has led to shortages of some goods, higher prices, port congestion, skyrocketing freight rates, and now threatens to slow the economic recovery.

CNBC wrote Wednesday that the White House plans to work with companies and ports to alleviate bottlenecks. Measures include getting the Port of Los Angeles to operate 24/7, something its rival Long Beach already does, thereby increasing the time spent unloading ships and getting more vessels currently at anchor into available berths.

President Biden apparently told an audience of port operators, truckers’ associations, labor unions, and executives from Walmart, FedEx, UPS and Target, that “For the positive impact to be felt all across the country and by all of you at home, we need major retailers who ordered the goods and the freight movers who take the goods from the ships to factories and stores to step up as well.”

Walmart, the nation’s largest retailer, has committed to a 50% increase in moving goods during off-peak hours. FedEx and UPS will also increase their overnight operations.

To address the truck driver shortage that has added to supply chain woes, the Department of Motor Vehicles is expected to increase the number of commercial drivers’ licenses it issues.

This is all well and good. However I would argue it misses the point completely. The problem isn’t US supply chains, it’s not a shortage of containers, rail cars, truck drivers, nor is it the fact that there are 100 freighters sitting at anchor, waiting to unload. If the United States had done things differently, they wouldn’t have a $73-billion-dollar trade deficit closing in on $1 trillion annually, and there would be much fewer container vessels stacked with cheap Asian goods, certainly not the number currently clogging up the country’s port, rail and road infrastructure.

Had the federal government been focused on protecting American jobs and the US manufacturing base, the current trade flows might actually be reversed, with more goods leaving American shores than are piling up on them.

The reality is, the United States hardly makes anything of importance, it is primarily a services-based economy that sucks in cheap goods from Asia — that is the fundamental problem.

Moreover, don’t be fooled into thinking these supply bottlenecks are all about the pandemic and that once relieved, trade flows will increase and help alleviate the trade deficit.

Successive administrations one after the other have gutted America’s manufacturing base. Gung-ho on globalization, they let overseas merchants supply everything from t-shirts and golf clubs to critical minerals — future-facing metals such as rare earths, lithium, graphite and cobalt.

The result has been a surge in imports and a slowing of exports. According to The Balance, 2020’s trade deficit was much higher than that of 2019, $676.7B versus $576.3B. Last year the United States imported $2.3 trillion in consumer goods while exporting only $1.4T worth, creating a $909.9B goods deficit that was the highest on record. In 2020 the country had a half-trillion-dollar deficit with its five largest trading partners; imports from China, Mexico, Canada, Japan and Germany out-paced US exports to these countries by $551.2 billion.

Sounds like a lot, but what’s wrong with a trade deficit? As mentioned at the top, deficits generally hurt job creation and economic growth. The Balance adds that an ongoing trade deficit is detrimental to the US because it is financed by debt:

The U.S. can buy more than it makes because it borrows from its trading partners. It’s like a party where the pizza place is willing to keep sending you pizzas and putting them on your tab. This can only continue as long as the pizzeria trusts you to repay the loan. One day, the lending countries could decide to ask America to repay the debt…

Another concern about the trade deficit is the statement it makes about the competitiveness of the U.S. economy itself. By purchasing goods overseas for a long enough period, U.S. companies lose their expertise and even the factories to make those products. As the nation loses its competitiveness, it outsources more jobs, which reduces its standard of living.

Key to understanding the trade deficit is the rise and fall of the US dollar. Basically a weak dollar helps exports and a strong dollar helps imports. Exporting countries thus prefer to keep their currencies weaker in relation to their trading partners, while nations that rely more on imports want to keep their currencies strong, benefiting consumers by making imports priced in other currencies cheaper.

The United States is uniquely beholden to trade deficits because it has the world’s reserve currency. While many including US President Trump have used the trade deficit as a kind of punching bag, while advocating for a lower dollar, the reality is the US dollar’s reserve-currency status goes hand in glove with a trade deficit. Politicians don’t seem to know this, but economists do, as do we at AOTH. What does it mean?

The Triffin Dilemma

The dollar as the world’s reserve currency can only go so low because it will always be in high demand for countries to purchase commodities priced in US dollars, and US Treasuries. Nor should it be allowed to go too low, because that would risk the dollar losing its “exorbitant privilege”.

Because the dollar is the world’s currency, the US can borrow more cheaply than it could otherwise, US banks and companies can conveniently do cross-border business using their own currency, and when there is geopolitical tension, central banks and investors buy US Treasuries, keeping the dollar high – self serving act, keep the dollar high, your currency low. A government that borrows in a foreign currency can go bankrupt; not so when it borrows from abroad in its own currency ie. through foreign purchases of US Treasury bills. The US can spend as much as it likes, by keeping on issuing Treasuries that are bought continuously by foreign governments. No other country can do this.

The cost of having this privileged status is the country that has it, must run a trade deficit with the rest of the world. It can’t have the strongest currency, and also keep the currency low in order to increase exports.

This is explained in a previous AOTH article titled ‘The Triffin Dilemma Will Create a 3G World’. Here is an excerpt:

When a national currency also serves as an international reserve currency conflicts between a country’s national monetary policy and its global monetary policy will arise.

“In October of 1959, a Yale professor sat in front of Congress’ Joint Economic Committee and calmly announced that the Bretton Woods system was doomed. The dollar could not survive as the world’s reserve currency without requiring the United States to run ever-growing deficits. This dismal scientist was Belgium-born Robert Triffin, and he was right. The Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1971, and today the dollar’s role as the reserve currency has the United States running the largest current account deficit in the world.

By “agreeing” to have its currency used as a reserve currency, a country pins its hands behind its back. In order to keep the global economy chugging along, it may have to inject large amounts of currency into circulation, driving up inflation at home. The more popular the reserve currency is relative to other currencies, the higher its exchange rate and the less competitive domestic exporting industries become. This causes a trade deficit for the currency-issuing country, but makes the world happy. If the reserve currency country instead decides to focus on domestic monetary policy by not issuing more currency then the world is unhappy.

Becoming a reserve currency presents countries with a paradox. They want the “interest-free” loan generated by selling currency to foreign governments, and the ability to raise capital quickly, because of high demand for reserve currency-denominated bonds. At the same time they want to be able to use capital and monetary policy to ensure that domestic industries are competitive in the world market, and to make sure that the domestic economy is healthy and not running large trade deficits.

Unfortunately, both of these ideas – cheap sources of capital and positive trade balances – can’t really happen at the same time.” — ‘How The Triffin Dilemma Affects Currencies’, investopedia.com

Conclusion

For the United States, the only way out of the Triffin Dilemma is for the US to quit the dollar being the world’s reserve currency. That would give the central bank the freedom to raise or lower interest rates, and increase or decrease the money supply, without fear of denting the value of the dollar in relation to other currencies which also lessens the government’s ability to borrow from its trading partners (through issuing Treasuries) to finance its debts and spending.

An analysis of reserve-currency alternatives is beyond the scope of this article, however suffice to say there are essentially three options, explained in detail in this Wall Street Journal piece: 1/ muddle along under the current “dollar standard”; 2/ turn the International Monetary Fund into a global central bank that issues “special drawing rights”, a kind of international reserve asset; 3/ adopt a modern international gold standard.

I’m not suggesting the country is anywhere close to dropping the dollar as the reserve currency. I only wish to point out there is a fundamental disconnect, in the United States, between domestic policy and the international monetary order.

Consider: despite everything that Trump did to try and lower the dollar, including badgering Fed Chair Jerome Powell and accusing China of devaluing the yuan, yet failed, Biden is attempting to do the same thing.

A New York Times article explains how Biden, like Trump, wants to revive American manufacturing. To deliver, he has to do something about the strength of the dollar, which according to a US dollar index chart DXY below, has mostly moved higher. Starting the year at 89.14, DXY currently sits at 94.00.

The president has reportedly hired a handful of senior economic advisers who are concerned about the dollar’s strength and have explored ways to reduce it. Sound familiar?

The Times notes the dollar’s strength over the past few decades has bloated the trade deficit which tripled as a share of gross domestic product in the 1990s and has remained high.

At its simplest level, the trade deficit represents a kind of leakage from the U.S. economy: Americans buy more in goods and services from abroad than the rest of the world buys from the United States, and the country takes on foreign debt to pay for the difference. If Americans bought more domestically made products and fewer imports, the spending would create jobs for U.S.-based workers and require less debt.

The above paragraph more or less summarizes my position, which is that the United States can’t continue to hold the world’s reserve currency if it wishes to devalue the dollar, thereby returning lost manufacturing jobs, increasing exports, and lessening the trade deficit which, at nearly $1 trillion, is getting as out of control as the $28 trillion national debt.

It can do one or the other, but it can’t do both. Time to stop seeing the dollar as a means of instant gratification and look to a more permanent solution that will allow the US to escape the Triffin Dilemma.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.