IRA blowback: restricting imports slowing electric vehicle adoption – Richard Mills

2024.02.26

The Inflation Reduction Act aims to grant incentives to companies that source their battery materials within the US and outside of China.

Passed by the Biden administration in 2022, the IRA provides US consumers tax credits of up to $7,500 per electric vehicle, provided the parts or materials are sourced from the United States, or from countries with which the US has a free trade agreement. This includes lithium, graphite, cobalt and other critical minerals.

As well as offering consumer incentives, the IRA subsidizes up to 30% of manufacturing costs related to battery cell assembly and battery pack production, helping to encourage carmakers and battery suppliers to invest in US-based supply chains.

According to Bloomberg, In the year after the passage of the IRA, investments totaling $55.1 billion for US battery manufacturing were announced along with $16.1 billion for EV factories. While that should eventually produce a wave of EV capacity, the immediate effect was far smaller, in part because so many US carmakers rushing to ramp up production have had to rely on Chinese technology that only 10 models now in production are eligible for the full IRA subsidy.

That is the dilemma facing the US government. It wants to create a US-centered electric vehicle supply chain (same with semiconductors, discussed separately below), but by imposing restrictions on China, which dominates the mining and processing of most metals needed for vehicle electrification, it is making things a lot tougher for EV- and battery-makers to source the raw materials, because the ‘Rest of the World’ don’t mine enough of them, process them into usable materials and manufacture the necessary components.

The problem is made worse by the fact that the prices of battery metals have tanked, leading to mine closures and a hiatus on bringing forward new mineral processing facilities like Albemarle’s $1.3 billion plant in South Carolina — making material sourcing, ex-China, more difficult.

Meanwhile, EV sales have slowed, due mostly to their high prices. Carmakers can’t make vehicles any cheaper if they source more expensive materials outside of China. Those that go to China won’t qualify for IRA subsidies, elevating sticker prices and making electric cars more difficult to sell.

Electric vehicles

The poster child for electric-vehicle success in North America is Tesla.

In 2023 the Texas-based company took the first four places in an annual ranking of the most American-made cars.

Ironic, given that Tesla’s batteries are made by Japan’s Panasonic and that, following the passage of the IRA, it took advantage of a loophole in the legislation by stocking up on cheap Chinese batteries.

That opening was slammed shut in December, when new Treasury guidelines prohibited automakers from buying batteries from China, if they want to benefit from IRA incentives. Suddenly, the search is on for ex-China sources.

According to the act, in 2023 at least half of the value of battery components had to be assembled in North America, with 40% sourced from the US or countries it has trade agreements with. This includes Australia, South Korea, Chile and Japan (presumably Mexico and Canada, too). Last year, there were five car companies with 14 models, powered by several kinds of lithium-ion batteries, that met these criteria, according to an analysis by CRU, quoted by Bloomberg.

GM, Tesla, Ford (F-150 Lightning) and Volkswagen qualified for the full tax credit, while Ford (Mustang MachE, E-Transit) and Rivian qualified for the partial tax credit.

CRU says carmakers could meet the 40% threshold by buying lithium from suppliers in Australia or Chile, or by processing lithium mined elsewhere in South Korea or the US (but not China or non-FTA countries such as the DRC, Indonesia or Finland).

CRU also states that seven of Tesla’s 12 models sold in the US qualified for the full $7,500 per vehicle tax credit, due to alliances with miners including Glencore, Albemarle and Panasonic.

Come 2024, however, the regulations tightened up. Now, EV-makers must source at least 50% of their raw materials from eligible countries. By 2027, the raw material requirement will increase to 80%.

After Jan. 1, eight of the above-mentioned vehicles became ineligible. CRU doesn’t identify which ones.

The organization points out that buying IRA-compliant materials will become difficult in some cases, such as cobalt, 70% of which is mined in the Congo. Indonesia supplies more than half of the world’s nickel.

These materials could become compliant if they are processed in an FTA country, but processing capacity is limited outside of China — something we at AOTH know full well and have written on extensively.

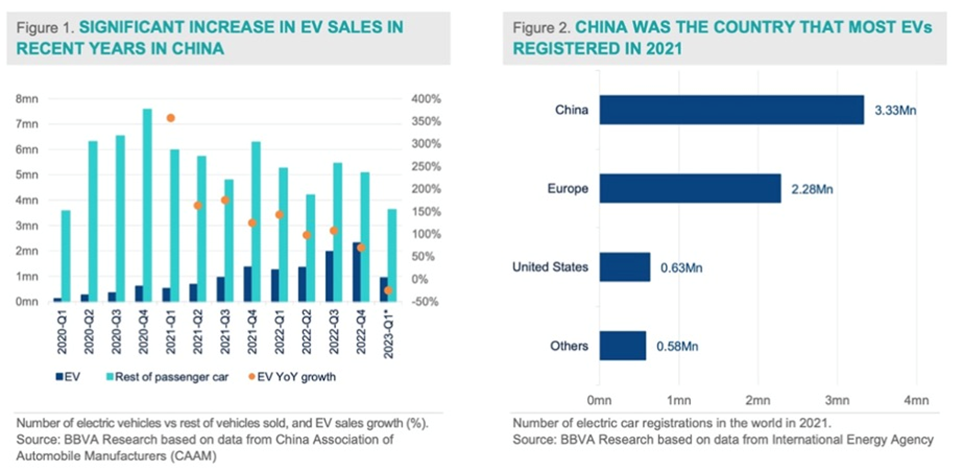

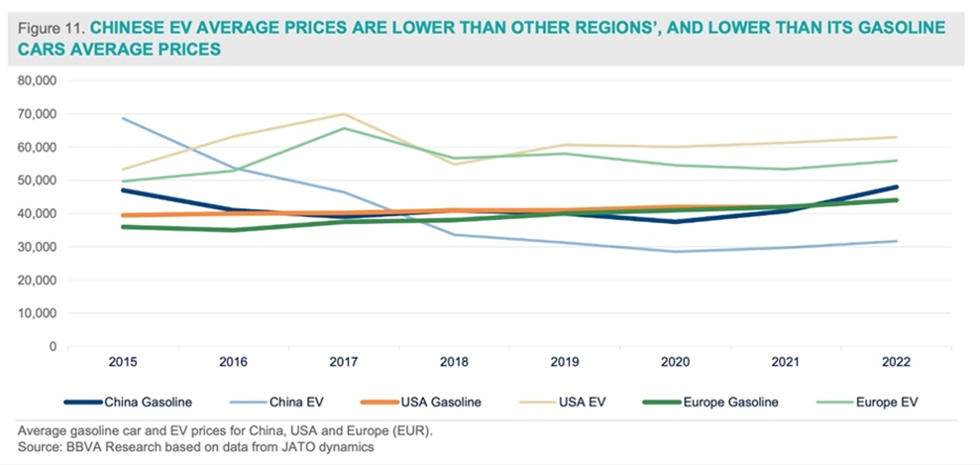

BBVA Research has some good data on China’s emergence as the global leader in the EV market.

About 70% of global battery production capacity is in China, and in 2022, seven of the world’s top 10 electric battery makers were in China. Contemporary Amperex Technology Co (CATL) is the world’s largest EV automaker with 37% of market share as September, 2023. Between CATL and BYD (16%), the two Chinese companies account for more than half the battery market for electric cars.

China Briefing reports China holds a dominant position in the EV supply chain, with over three-quarters of the world’s battery production capacity. The country houses more than half the world’s processing and refining capacity for lithium, cobalt and graphite. It boasts 70% of the global production capacity for cathodes and 85% for anodes.

Moreover, China’s EV manufacturing industry has a 20% cost advantage over US and European markets. This is due to government policies that support the EV industry, including subsidies and tax incentives, at the national and regional levels.

China’s dominance in both battery manufacturing, and in procuring and processing the raw materials required for the EV supply chain, is aptly demonstrated in two tables by Visual Capitalist.

The first table shows that in 2022, China had more battery production capacity than the rest of the world combined.

The second table shows China leading the pack in 2027, when global lithium-ion manufacturing capacity is project to be eight times higher than in 2022.

Business Insider notes that China has achieved EV leadership status by making its batteries cheaper. The country is one of the biggest producers of lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries which do not contain the relatively expensive minerals cobalt and nickel.

The IRA was supposed to create an alternative supply network around the US and its free-trade partners. However, the evidence suggests the act has taken carmakers by surprise and its provisions were rolled out too soon.

Consider that Tesla lost the $7,500 IRA tax credit on its most affordable Model 3, due to batteries imported from China’s CATL. Ford plans to source low-cost LFP batteries from CATL for its Mustang MachE and F-150 Lightning truck. Both companies have lobbied against ending the use of cheap Chinese batteries.

In December, Beijing reacted to the IRA legislation by imposing limits on graphite exports.

Moreover, tariffs are still in place on specified goods imported from China — a leftover from Trump’s trade war — including those used in the automobile industry. This is another barrier to lower sticker prices.

The Bloomberg article says one solution is for the United States to use Korea as a source for battery materials. The country, a long-time US ally, is already home to three of China’s biggest battery rivals: Samsung SDI, LG Energy Solution and SK On.

Since the IRA came into force, Korean companies including joint ventures with US firms have committed almost $48 billion to build new battery plants at home and in North America.

But Korean battery makers have historically been reliant on raw materials sourced from China, and counter-measures like China’s graphite export restrictions are causing concern.

Even if Korea can source the materials from IRA-compliant countries, it must still compete with China on processing them. Bloomberg notes a flood of Chinese investment into Indonesia’s nickel industry helped give the country a huge cost advantage over other producing nations, like Australia and the Philippines, (at the cost of the environment — Rick) and with prices plunging, many miners outside Indonesia are shutting operations.

The future of Canada’s nickel supply is not Indonesia

(Wall Street Journal reports Glencore last week said production would be suspended at an unprofitable nickel mine in New Caledonia. A few days later, BHP said it may need to shutter its Australian nickel business, despite supply deals with Tesla and Ford. IGO says it can’t find a way to make its Cosmos nickel operation in Western Australia viable, and will close the gates by the end of May.)

Moreover, if Seoul gets too close to Washington, it could end up alienating Beijing, its biggest export partner.

“We will put our national interest first in terms of economic cooperation with China,’’ the country’s finance minister told a hearing of lawmakers on Dec. 19.

To clarify our position, we agree 100% on the need to diversify critical mineral supply chains away from China. This is a long time coming. What we disagree on, is maintaining dependence on other countries for mining and processing minerals, when this could be done domestically, in the United States or Canada.

Two examples are cobalt in the DRC and semiconductors.

Cobalt in the DRC

After World War II, the United States created the National Defense Stockpile (NDS) to acquire and store critical strategic materials for national defense purposes.

Without just a few critical minerals, such as cobalt, manganese, chromium and platinum, it would be virtually impossible to produce many defense products such as jet engines, missile components, electronic components, iron, steel, etc. This places the US in a vulnerable position, with a direct threat to its defense production capability, if the supply of strategic minerals is disrupted by foreign powers.

Despite this, in 1992 Congress directed that the bulk of the strategic and critical materials the US had accumulated in the National Defense Stockpile be sold.

This included cobalt, used in electric vehicle battery cathodes. Even though EV sales have slowed, demand for cobalt is expected to double by 2030.

Also, the only domestic US cobalt mine has been shuttered for more than a year due to low prices.

The need for cobalt is thus pushing US government officials to the DRC, where 70% of the metal is mined — much of it illegally, and under deplorable conditions including the use of child labor.

The DRC just turned the screws on cobalt supply

According to Bloomberg, after receiving $1 billion from Congress in 2021, to avoid a funding crisis that would have seen the NDS reach a breaking point by 2025, officials traveled to South America, Africa and Southeast Asia, trying to build diplomatic relations with countries rich in critical minerals.

(As we know, the Biden administration prefers to leave “dirty” mining and mineral processing to foreign countries, and instead invest in cleaner, more upstream activities like battery EV manufacturing. The Economist writes that America is sitting on a backlog of almost 300 mining projects, and many big schemes have been stuck in licensing limbo for years, with no resolution in sight.

Resource nationalism is happening in several countries known for their mineral endowments. Chile, a world leader in copper and lithium mining, last year announced plans for a state-owned company to produce lithium. Others, including Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Mexico and Namibia, are charging sky-high royalties, implementing export bans and indulging in other forms of state intervention, states The Economist.

How governments can help accelerate the mining of critical minerals, and the obstacles in the way

Governments aren’t only to blame; it’s also falling investment and less spent by the mining companies themselves. Capital expenditures in mining fell from approximately $260 billion in 2012 to $130 billion in 2020 McKinsey & Company found.

In 2022, the 40 largest mining companies invested a total $75 billion, equivalent to only a quarter of EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization). The world’s largest miner, BHP, invested $8.8 billion last year, less than half what it spent in 2013.

Junior mining financing has pretty much dried up; global exploration budgets in 2021 were half of what they were in 2012. Since it can take up to 20 years to go from discovery to production, you can see we are squarely behind the eight ball in our efforts.

Last year for the first time in a decade, there wasn’t a single financing about $125 million on the TSX Venture Exchange, according to data from the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC). Deals at the $200M level were previously common.)

Efforts to secure cobalt supplies have so far focused on the Congo. The problem is that many Western companies have left the country after what Bloomberg describes as a slew of problems — from asset seizures to billion-dollar corruption cases — cemented Congo’s reputation as one of the world’s most risky mining jurisdictions.

For example, Freeport-McMoRan sold its majority stake in the Tenke Fungurume cobalt-copper mine to China’s CMOC Group in 2016.

Now, the story goes on to say, US officials have been deployed to convince people that times have changed. (Yeah, right — Rick)

This includes Helaina Matza, who oversees Biden’s infrastructure investment program, visiting several mining projects in Congo in October, 2023; and encouraging financing for copper and cobalt assets in the region.

Washington has also agreed to help finance parts of the $2.3 billion project to rebuild and expand the Lobito railway corridor, the copper belt in Zambia and Congo, to Angola’s Atlantic Coast, Bloomberg states.

Funny how the Biden administration is seeking security of cobalt supply in a country that consistently ranks poorly on the UN Human Development Index (HDI), which represent an annual assessment of measures of progress in human well-being. Countries at the bottom of the list suffer from inadequate incomes, limited schooling opportunities and low life expectancy rates due to preventable diseases such as malaria and AIDS.

In a previous article, we wrote that life expectancy in the Democratic Republic of Congo is less than 48 years, one of five children will die before age five, and almost 60% of the country’s 71 million people live on less than $1.25 per day.

The DRC is also racked by political violence in eastern Congo, where clashes between the DRC’s army and Rwanda’s Tutsi-led rebels have killed many people and displaced hundreds of thousands.

On Tuesday, it was reported that Prime Minister Jean-Michel Sama Lukonde resigned, and the government was dissolved, after France said earlier in the day it was “very concerned” about the situation in the eastern part of DRC and called on Rwanda to cease its support for the M23 rebel group, which has recently stepped up its offensive.

So, let’s summarize this bizarre situation. The goal is to obtain a safe, sustainable supply of cobalt, so the United States’ first move is the DRC, “the rape capital of the world”, where major miners and big tech companies are fleeing because they don’t want to be associated with child labor and environmental destruction from illegal mining. Big mining companies also fear resource nationalism, where the government could expropriate assets and offer little to no compensation. (this happened to the Frontier copper mine in 2010, when it was owned by First Quantum Minerals.)

Also, if the goal is to reduce dependence on China, Congolese cobalt is the last place the US should look.

China controls about 85% of global cobalt supply, including an offtake agreement with Glencore, the largest producer of the mineral, to sell cobalt hydroxide to Chinese chemicals firm GEM. China Molybdenum is the largest shareholder in the major DRC copper-cobalt mine Tenke Fungurume, which supplies cobalt to the Kokkola refinery in Finland. China imports 98% of its cobalt from the DRC and produces around half of the world’s refined cobalt.

By investing in a railway corridor and “encouraging financing for copper and cobalt assets in the region,” the US is actually helping the Chinese to ship more cobalt from the DRC to China for refining, so they can sell the finished product to the West.

Semiconductors

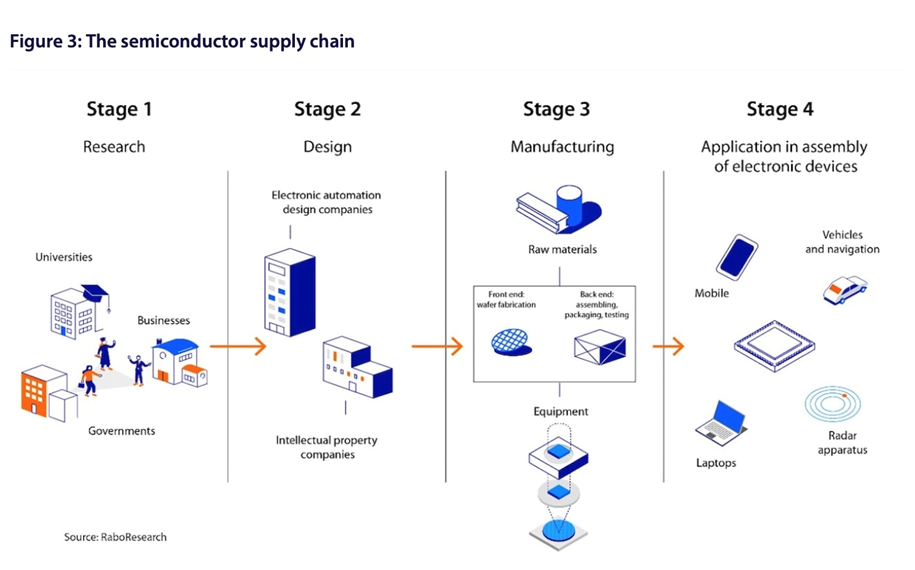

During the pandemic, a shortage of semiconductors hit the auto industry hard. The tiny chips are used for analyzing engine temperature and pressure sensor data, adjusting the fuel injection for optimum combustion, optimization of ignition timing and managing emissions.

S&P Global Mobility estimates that in 2021, more than 9.5 million units of global light-vehicle production was lost as a direct result of a lack of necessary semiconductors, with the third quarter of 2021 experiencing the largest impact with an estimated volume loss of 3.5 million units. Another 3 million units were impacted in 2022.

While production in 2023 improved, the pre-pandemic momentum toward a 100-million global vehicle production year has been set back by a decade, according to S&P Global Mobility analysis.

Semiconductors are considered to be the world’s most fragile supply chain because the industry is so complex — involving hundreds of materials and chemicals, more than 50 types of high-tech equipment, and thousands of suppliers across Europe, North America and Asia.

Just one break can interrupt the entire chip supply ecosystem, causing delays and shortages of chips for the many industries that rely on them.

Fabricating chips takes three to four months and over a thousand manufacturing processes. It must be done in a pristine environment and requires precision equipment that manipulates particles on sub-atomic levels.

According to Peter Zeihan, an American geopolitical expert and author, there are over 6,000 firms globally involved in semiconductor fabrication for the 10-nanometer and better chips. Of these, 5,000 are involved with Dutch firm ASML, responsible for the lithography part of the production process. “Most of those firms have no global competition,” says Zeihan, “they’re highly specialized. They do one thing for ASML, and most of them only have AMSL as a customer… You miss a few of those pieces and ASML in its current form cannot function.”

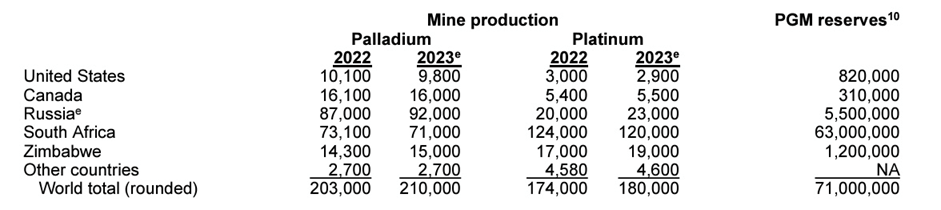

The other problem with semiconductors, as it relates to this article, is the raw material inputs. Semiconductors require palladium and neon, both of which are controlled by Russia. One Russian mine owned by Norilsk Nickel produces 40% of global palladium, and Russia is the largest supplier of the metal to the United States.

When the war in Ukraine began in February 2022, many reports highlighted how reliant the Western world is on palladium from Russia. As the table below from the USGS shows, 92,000 kilograms of palladium were mined by Russia in 2023, higher than second-place South Africa’s 71,000 kg, and nearly six times more than Canada’s 16,000 kg.

When UK sanctions targeted Russian metals in December, 2023, but excluded palladium, the metal surged 12% to its biggest gain since March, 2020.

Zeihan states there is a two-country supply chain to produce neon, which is used to focus the apertures of the etching lasers. The first stage is in Russia and the second stage was in Mariopol, Ukraine, but those sites were destroyed by Russia, meaning the loss of “a conservative half” of neon, Zeihan said during a 2023 video (the part on semiconductors starts at 24:23)

A shortage of neon during the first Russia-Ukraine war in 2014 led to a 6,000% increase in the price of neon; in 2022, the price rose 5,000%. However, the fallout wasn’t as dire as Zeihan expected, with chipmakers drawing on their rare-gas reserves and investing in technology that enables recycling.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) reportedly worked with suppliers to secure local sources of neon gas.

“The prices did shoot up but now have come back down and semiconductor supplies are good,” futurist and science blogger Brian Wang wrote in April, 2023.

Still, the vulnerability of the semiconductor supply chain, and the danger of it being hijacked by China, has led to a series of policy announcements by the US government that have ratcheted up tensions between the United States and China. The biggest risk is a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, which produces 92% of the world’s most advanced logic chips (at node sizes less than 10 nanometers), as well as a third to half of the global output for less sophisticated but nonetheless critical chips. Taiwan’s leading chip foundry TSMC produces 35% of the world’s automotive microcontrollers and 70% of the world’s smartphone chipsets. It also dominates in the production of chips for high-end graphics processing units in PCs and servers.

The US banned Chinese telecommunications firm Huawai from buying advanced computer chips used with US technology, and followed that up with a set of rules aimed at cutting off exports of key chips and semiconductor tools to China.

Beijing responded by imposing export restrictions on gallium, used to make radio frequency chips for mobile phones, satellites and semiconductors, and germanium, required in solar products, fiber optics and military applications such as night-vision goggles.

In August 2022, the CHIPS and Science Act was signed into law, providing for $280 billion in funding to boost research and manufacturing of semiconductors in the United States.

Taiwan-based TSMC, the world’s largest semiconductor manufacturer, is spending $40 billion to build two fabs (short for fabrication plants) in Arizona.

Redundancies are also being built into the semiconductor supply chain through investments in Japan, which is aiming to rebuild its industry having lost market share. According to Reuters, at least nine Taiwanese chip firms have set up shop or expanded operations in Japan in the last two years, including the opening this weekend of TSMC’s first plant on the southern island of Kyushu, a chipmaking hub.

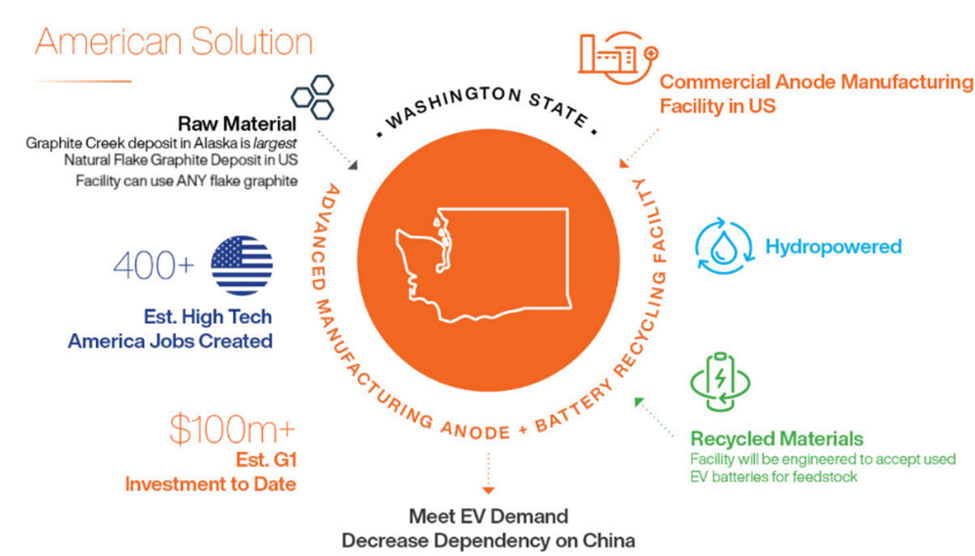

Graphite One

Whether we are talking about Russian palladium and neon for semiconductors, cobalt in the DRC for lithium-ion batteries, or the myriad of critical metals controlled by China, one way to rely less on other countries for the preservation of important supply chains is to mine domestically, meaning in the United States or Canada.

One of the battery metals the world needs more of is graphite, a key ingredient in EV batteries and energy storage systems for which there are no substitutes.

Analysts estimate that by 2030, it will take at least 5 million tonnes of graphite per year to fill battery demand. This is roughly triple the 1.6 million tonnes mined globally, according to the USGS’s Mineral Commodities Summaries 2024.

This is why the Department of Energy ranked graphite near the top of its list of minerals critical to America’s energy future. The US federal government’s critical minerals list also has graphite as one of five key battery minerals that are at risk of supply disruptions.

The only way to alleviate that risk is for the United States to find its own source of graphite production, and at AOTH we believe a project like Graphite One’s Graphite Creek deposit ticks all the boxes.

The results of its 2022 drill campaign demonstrate the potential, in my opinion, for significant resource expansion. Step-out hole 22GC079 was the furthest step-out from the campaign, collared over 2 km west of the next closest hole and 4 km west of the PFS pit boundary. It intercepted a combined 58.2m of mineralization averaging 4.18% graphite. These are excellent grades; flake graphite ore suitable for electric-vehicle batteries typically grades 2-3% Cg.

The 2023 drill program was designed to double the measured and indicated resources and increase the inferred resource by infill drilling along trend to hole 22GC079.

In October, Graphite One announced the completion of the 2023 drill program along with a selection of assay results. The program quadrupled the scope of 2022’s drilling program, with 57 holes completed for a total of 8,736 meters — the largest drill program in GPH’s history. Of the 57 holes, 5 holes were geotechnical and the remaining 52 resource holes all intersected visual graphite mineralization and continued to demonstrate exceptional consistency of a shallow, high-grade graphite deposit that remains open both to the east and west of the existing mineral resource estimate.

Graphite One could represent a significant portion of the amount of graphite demanded by the United States, currently.

Consider: In 2023, the US imported 83,000 tonnes of natural graphite, of which 89% was flake and high-purity, suitable for electric vehicles.

Based on the prefeasibility study, the Graphite Creek mine is anticipated to produce, on average, 51,813 tonnes of graphite concentrate per year during its projected 23-year mine life.

If all goes according to plan, the feasibility study — ahead of schedule by one year — would move Graphite One’s Graphite Creek deposit that much closer to becoming America’s only source of mined graphite, helping to shed its import reliance. (In fact, the FS contemplates a tripling of production, from 50,000 tonnes of graphite concentrate per year as estimated in the PFS to more than 150,000 tonnes)

More broadly speaking, Graphite One’s activities should be considered a bolt-on to what is already happening in northwestern Alaska with respect to the building of the first deepwater port in the US Arctic region.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Alaska’s Department of Transportation have chosen two sites for a deepwater port facility: Nome and Port Clarence. Nome has received $600 million in government grants and appears to be well on its way to doubling the size of its existing port to accommodate the world’s largest commercial and military vessels. Work is expected to start this year.

Port Clarence is only about 25 miles from Graphite One’s Graphite Creek deposit, meaning G1 could become an anchor customer for a port on BSNC land at Point Spenser. Both Port Clarence and Nome are within a short distance of Graphite Creek and could easily be connected by road.

While the development of Graphite Creek is in feasibility study stage, the project has been given a leg up by the federal government, which in 2021 gave the project High-Priority Infrastructure Project (HPIP) status. This ensures that the various federal permitting agencies coordinate their reviews of projects as a means of streamlining the approval process. In other words, having HPIP means that Graphite Creek will likely be fast-tracked to production.

The company has political help from the highest political offices in Alaska — the governor and senators. They clearly see an investment to increase domestic capabilities for graphite as money well spent.

The Bering Straits Native Corporation has pledged its support for the project including an up-front US$2 million investment with an option to increase its investment up to US$10.4 million.

The United States must build port infrastructure and start developing this region if it wants to maintain Arctic sovereignty, and we see Graphite One’s Graphite Creek project as fitting in perfectly with these plans.

We see Graphite One taking a leading role in loosening China’s tight grip on the US graphite market by mining feedstock from its Graphite Creek mine in Alaska and shipping it, either through Nome or Port Clarence.

In the first quarter, G1 plans to submit a proposal to the US Department of Energy seeking a grant for a precursor development plant and an early-stage commercial synthetic graphite anode facility.

Q1 2024 is also expected to see Graphite One select a site for its natural graphite anode material production facility, in keeping with the company’s US-based graphite supply chain strategy involving mining, manufacturing and recycling, all done domestically.

Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski

(use slider to 1:48)

Pentagon support accelerates Graphite One

Graphite One Inc.

TSXV:GPH, OTCQX:GPHOF

2024.02.23 share price: Cdn$0.85

Shares Outstanding: 129.0m

Market cap: Cdn$112M

GPH website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Richard does own shares of Graphite One Inc. (TSXV:GPH). GPH is a paid advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

This article is issued on behalf of GPH

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.