Inomin eyeing monster BC nickel sulphide deposits

2019.11.23

Canada has long enjoyed a reputation as one of the world’s leading nickel-mining nations. The base metal used in the production of stainless steel, and increasingly, in nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) and nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) lithium-ion batteries needed for electric vehicles – was first discovered in Canada in 1883.

Bullish on nickel

Nickel is an interesting metal to watch, considering the challenge that nickel miners face in ramping up production to meet rising demand for it in EV batteries. Tesla has expressed concern over whether there will be enough high-purity “Class 1” nickel needed for electric-vehicle batteries.

According to Bloomberg, EV sales are expected to increase 10-fold by 2025, 27X by 2030 and 50X by 2040. JP Morgan is forecasting electric cars to be 35% of the global auto market by 2025 and 48% by 2030.

Nickel is becoming more and more important as a battery metal due to its use in nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) and nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) Li-ion batteries. NMC 811 battery cells (8 parts nickel, 1 part each lithium and cobalt) are being produced on a greater scale.

However, the nickel market is currently under-supplied and likely to be so for the foreseeable future. This past July LME nickel shot past $18,000 per tonne for the first time in five years, on account of nickel inventories in LME warehouses dropping to 150,000 tonnes. As we reported, this was a result of a massive drawdown in nickel inventories by China’s Tsingshan Group, the largest stainless-steel producer in the world. Tsingshan is heavily invested in Indonesian nickel and it appears to us that China is using Indonesia’s upcoming raw ore export ban to try and corner the nickel market.

The Indonesian government has stated the nickel export ban wil take effect at the start of 2020. As nickel from Indonesia supplies approximately 12% of the global nickel market, the ban is significant. Buyers of Indonesian nickel will need to source nickel elsewhere.

Nickel sulfide deposits provide ore for Class 1 nickel users which includes battery manufacturers. Class 2 nickel is primarily used to make stainless steel, which accounts for two-thirds of global nickel demand.

According to BloombergNEF, demand for Class 1 nickel is expected to out-run supply within five years, fueled by rising consumption by lithium-ion electric vehicle battery suppliers. This year, Sumitomo Metal Mining predicts the nickel market will be 51,000 tonnes in deficit. According to figures released by the World Bureau of Metal Statistics (WBMS) in early October apparent demand exceeded production by 77,100 tonnes.

To understand Tesla’s concerns over whether there will be enough high-purity “Class 1” nickel needed for electric-vehicle batteries we need to know about the two types of nickel deposits, sulfide or laterite. About 60% of the world’s known nickel resources are laterites. The remaining 40% are sulfide deposits.

The main benefit to sulfide ores is that they can be concentrated using the traditional flotation technique. Most nickel sulfide deposits have been processed by concentration through a froth flotation process followed by pyrometallurgical extraction.

By contrast, there is no simple separation technique for nickel laterites. The rock must be completely molten or dissolved to enable nickel extraction. As a result, laterite projects require large economies of scale at high capital costs, to be viable. They are also generally much higher cash-cost producers than sulfide operations.

Large-scale sulfide deposits are extremely rare. Historically, most nickel was produced from sulfide ores, including the giant (>10 million tonnes) Sudbury deposits in Ontario, Norilsk in Russia and the Bushveld Complex in South Africa, known for its platinum group elements (PGEs). However, existing sulfide mines are becoming depleted.

Will annual world nickel production of around 2.3 million tonnes be enough to satisfy both stainless steel and battery demand? Less than half of total nickel output is Class 1, suitable for conversion into nickel sulfate used in battery manufacturing. Last year, only around 6% of nickel ended up in EV batteries; remember, 70% of supply goes into making stainless steel.

Class 1 nickel powder for sulfate production enjoys a large premium over LME prices ($2,000-$3,000/t) but for miners to switch to battery-grade material requires huge investments to upgrade refining and processing facilities. We’re talking in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

According to McKinsey, if there are 31 million EVs by 2025, demand for Class 1 high-purity nickel would increase 17X, from 33,000 tonnes in 2017 to 570,000t – “A shortfall in class 1 nickel production seems increasingly likely,” the consulting firm states.

From this analysis, it’s clear that more sulfide nickel deposits suitable for Class 1 battery-grade nickel will need to be found.

Inomin Mines (TSX-V:MINE)

Enter Inomin Mines (TSX-V:MINE), a junior exploration company focused on nickel and cobalt in British Columbia.

BC is probably best known for its porphyry copper/ gold mineralization. These deposits contain the largest resources of copper, significant molybdenum and 50% of the gold in the province. Examples are big copper-gold and copper-molybdenum porphyries, such as Red Chris and Highland Valley. Large, undeveloped porphyry deposits along the North American Ring of Fire include Galore Creek in BC and the Pebble project in Alaska.

However, it doesn’t really matter what you’re mining; if you’ve got the rocks in the ground to make a project economic, the scale, and a long-enough life of mine to interest a funding or mining partner, it makes sense to develop the deposit.

Being a nickel buff from way back, my interest was piqued earlier this month, in reading “Inomin Acquires Nickel Properties”. According to the Nov. 4 news release, Inomin has laid claim to two properties in central BC, Beaver and Lynx, not far from Williams Lake and 150 Mile House.

In fact the 7,528 hectare Beaver and 12,662 hectare Lynx are located smack dab in the middle between two major BC mines overlying world-class porphyry deposits – Taseko’s Gibraltar mine and Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley. Gibraltar is the second largest open-pit copper mine in Canada.

Mining “close-ology” dictates the importance of developing a mine that is nearby, or located within similar geology, to an existing producer(s). Even better if that producer is mining a porphyry – defined as a large mass of mineralized igneous rock, consisting of large-grained crystals such as quartz and feldspar.

Porphyry deposits are usually low-grade but large and bulk-mineable, making them attractive targets for mineral explorers. In British Colombia the average is 0.40 Cu Eq – other metals such as gold, molybdenum and silver are by-products.

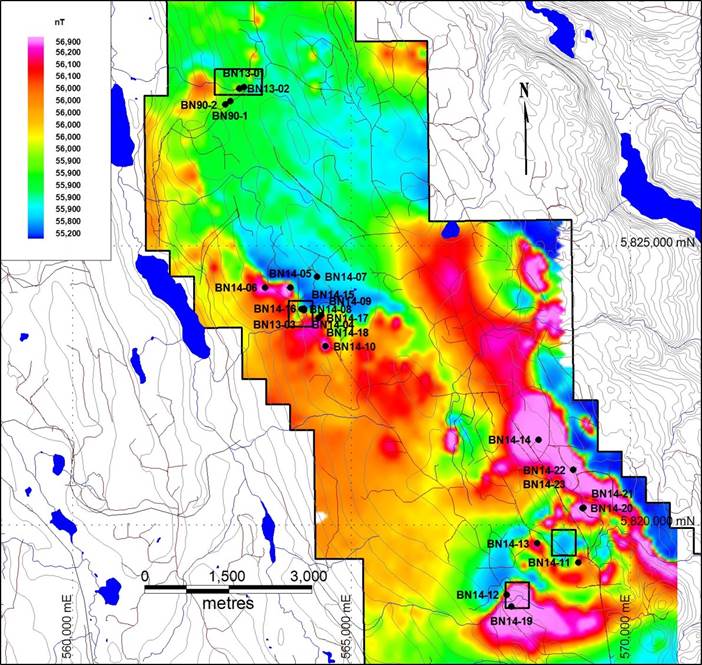

The Beaver property has seen quite a bit of exploration, though not enough to delineate a resource. A 2,187-meter drill program in 2014 consisted of 19 diamond drill holes that intersected fairly uniform nickel sulfide and cobalt concentrations. Highlights included 157.3 meters, 106.6m, and 86m, all containing 0.18% nickel and 0.01% cobalt. Uniform indeed.

According to the news release,

The ultramafic rock hosting the nickel, delineated by magnetic surveys and drilling, covers a large 4 km by 8 km footprint, indicating the property’s potential for large, bulk tonnage, near-surface nickel deposits with cobalt credits.

Don’t let the low grades dampen your enthusiasm. A little back-of-the envelope math by yours truly shows the potential for an impressive nickel-cobalt deposit of significant scale to interest a major mining company or funding partner.

Let’s check out potential tonnage for MINE’s Beaver project only. Take that 4×8 km area, and multiply, giving us 32 square kilometers. Each square kilometer is a million square meters, so we have 32 million square meters. Assume an average depth of 12 meters and a specific gravity (SG) of 3.5.

32,000,000 sq. meters x 12 meters deep x 3.5 SG = 1,344,000,000 b/t.

Setting an average grade of 0.20% nickel results in 4.4 pounds of nickel per tonne. At current nickel prices of around US$6.50/tonne, that works out to US$28.66/ Cdn$38.11 per tonne rock.

Of course, a percentage of the rock will not be ultramafic and some of it will not be recoverable. But even at a very conservative potentially mineable estimate we are talking about belonging to an enviable peer group!

I’m not making this up. The latest technical report for the Gibraltar mine showed a copper-equivalent grade of 0.27% CuEq, or US$14.20/ton. If the Beaver property can manage an only nickel grade – using no other metal credits like the contained cobalt – of 0.20%, the in-situ value per tonne would be US$25.80 @ the current US$6.50t price of nickel, equivalent to an only copper deposit grading 0.49% (BC copper deposits average 0.40% CuEq).

Drill assays, magnetic surveys (airborne and ground), as well as rock and soil sampling, demonstrates the promise of widespread mineralization at the Beaver target.

It’s important to mention that the metallurgy at Beaver has already been tested, though not proven. A pre-scoping metallurgical study in 2015 demonstrated that 90% of the nickel is within nickel sulfide minerals, heazlewoodite and pentlandite. In other words, 91% of the nickel should be recoverable. Initial testing revealed good recoveries from conventional flotation methods, or possibly lower-cost heap leaching.

The Lynx project is less-explored than Beaver but it is almost twice as large – suggesting a tantalizing upside.

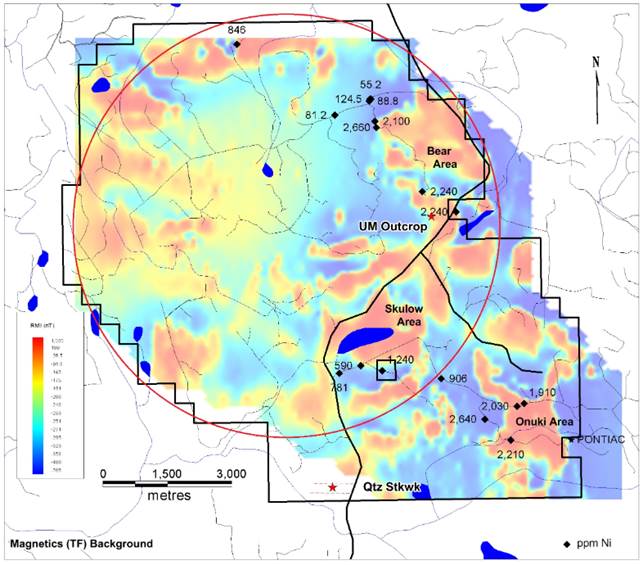

An airborne survey in 2014 delineated an 8-km, ring-like anomaly and at least three other strong magnetic anomalies over 2 km long. Those areas – Bear, Skulow and Onuki – revealed 17 rock samples chipped from outcroppings containing 0.27% nickel. “Exploration demonstrates the Lynx property shows potential for several very large, bulk-tonnage nickel deposits,” states Inomin.

Eight kilometer wide ring like magnetic anamaly and several strong magnetic anomalies

Copper porphyry analogs

So how does Inomin’s Beaver/ Lynx in-situ metal horde compare to British Columbia’s famed copper-gold mines built on monster porphyry deposits? As it turns out, quite well. Ahead of the Herd did some deep research to ascertain the reserve levels of the biggest copper porphyry operations in BC when they started mining.

Highland Valley

Currently owned and operated Highland Valley Copper, a subsidiary of Teck Resources, the Highland Valley mine is about 17 km west of Logan Lake. It produces copper and molybdenum concentrates through autogenous and semi-autogenous grinding and flotation.

First production was from the Bethlehem mine way back in 1962.

After the Lornex mine within the same complex opened in 1972, Highland Valley became the province’s leading copper-producing district, and was the second largest copper mine in the world behind Chile’s Chiquicamata.

In the early 1990s, ore reserves in the Highland Valley were estimated at 750 million tonnes containing 3 million tonnes of copper, according to a 1993 BC government report; in 1991 copper production was 177,500 tonnes.

A 2012 technical report shows Highland Valley’s reserves had dropped to 697 million tonnes, grading 0.291% copper and 0.0079% molybdenum, based on $2.70/lb Cu, $13.60/lb molybdenum, $16/oz silver and US$1,010/oz gold.

Fast forward to 2018, and Highland Valley is still cranking out the red metal, albeit at a lower rate. Highland Valley’s proven and probable reserves were about half what they were in the early ‘90s – 383 million tonnes at 0.32% Cu and 0.003% Mo.

But the mine has enough reserves to keep it going almost another decade, after a $475 million mill upgrade in 2013, upping capacity by about 10% and copper recoveries by 2%. It’s expected to produce between 100,000 and 150,000 tonnes of copper per year, to the end of mining in 2028. 2018’s copper production was 100,800t.

Red Chris

Imperial Metals acquired the Red Chris project in 2007 and took two years to construct the mine; it opened in 2014 at a cost of $662 million. A 2010 feasibility study showed reserves of just over 300 million tonnes grading 0.349% copper and 0.274 g/t gold. A 2012 reserve estimate – the latest – is virtually unchanged.

The 30,000-tonnes-per-day open-pit mine is expected to produce until 2043. Imperial pegs the life-of-mine production cost at $1.22 per pound of copper. Based on $2.20 copper, $12 silver and $900 gold, Red Chris has a 15.7% after-tax internal rate of return, with a project payback of 4.58 years.

In March of this year, Imperial sold a 70% interest in Red Chris to Australia’s Newcrest Mining. The two companies formed a joint venture whereby Imperial retains a 30% interest and Newcrest is the operator.

Copper Mountain

The mine close to Princeton, BC was purchased by Copper Mountain Mining in 2006, which began aggressively drilling the property with an eye to production, which started in 2011. An interim resource estimate in January, 2008 documented 260 million tonnes grading 0.36% copper, measured and indicated. A bankable feasibility study showed a 35,000 tpd operation, producing about 100 million pounds of copper annually, based on a long-term copper price of $1.80/lb.

The conventional open-pit mine cranked out 92.4 million pounds of copper-equivalent in 2018; it is expected to keep producing until 2042. The mine is 75% owned by Copper Mountain Mining and 25% by Mitsubishi Materials Corporation of Japan.

A recent corporate presentation shows proven and probable reserves of 593.8 million tonnes, with grades of 0.26% copper, 0.10 g/t gold and 0.73 g/t silver– enough ore to produce 3.501 million tonnes of copper, 1.8 million ounces of gold and 11.125 Moz silver.

Gibraltar

Originally built in 1971 by Placer, Taseko purchased the Gibraltar mine in 1999 while it was on care and maintenance. It was restarted in 2004 with a $700 million capital investment and an exploration drill program that increased reserves and extended the mine life to 25 years.

An 80% expansion in 2011 pushed proven and probable reserves from 445 million tons to 802Mt, at the operation 65 km north of Williams Lake.

Currently, as Canada’s second largest open-pit copper mine, Gibraltar has proven and probable reserves of 667 million tons grading 0.26% copper and 0.008% moly, with 3.0 billion lbs of recoverable copper and 53 million lbs of molybdenum.

Annual production targets 40 million lbs of copper and 2.6 million lbs of molybdenum. However in 2018 the mine only produced 125.2 million pounds 2.4 million pounds of moly.

Taseko’s 2018 annual review reports a net loss for the year of $35.8 million, owing to lower copper prices. Copper head grades were 3% lower than the LOM reserve grade. Total operating costs were $1.93 per pound.

Mount Polley

Construction at Mount Polley was completed in 1997, including an 18,000 tonne-per-day mill. About 27.7 million tonnes of ore, grading 0.563 g/t gold and 0.332% copper were mined at Mount Polley prior to suspension of operations in 2001. A 2004 feasibility study showed the viability of re-starting the mine for 6.25 years, during which 40.7Mt of ore would be mined from three pits.

At the time, proven and probable reserves were 40.7 million tonnes graded 0.432% copper and 0.309 g/t gold. Twelve years later, a 2016 a technical report was commissioned, showing 53.7 million tonnes of proven and probable reserves (open-pit and underground) at 0.34% Cu and 0.3 g/t Au and 0.9 g/t Ag. The mill has capacity to process 16,800 tonnes per day.

Mount Polley was placed on care and maintenance earlier this year for remediation work as a result of a tailings pond breach.

Obviously a comparison of these five operating copper mines to an earlier-stage exploration project like Inomin’s Beaver-Lynx project invites a considerable margin for error, we admit that, we’re not covering it up. But our very conservative back-of-the-napkin estimate of one billion tonnes of in-situ Ni grading 0.20%, with no cobalt credits yet added, has to put the Beaver deposit on the minds of the miners operating BC’s biggest mines, just next door.

The Beaver deposit, at a reasonable 0.20% nickel grade, has to have its potential considered in the same way as the two most copper-endowed mines we’ve analyzed, Gibraltar and Highland Valley, were considered when found – massive tonnage, long life, scalable mines that are a bedrock of company cashflow measured not in years, but decade after decade after decade.

Note that of these six mines, all but one are in operation. Five mines out of six increased their reserves, all will be mining into the mid-2020s, and two will still be operating until 2043.

Nickel analogs

Inomin of course isn’t mining copper-gold; it’s after nickel and cobalt. And there’s competition. Taking a look at its neighbors. The closest nickel deposit to Inomin’s Beaver-Lynx deposits is FPX Nickel (TSX.V:FPX)) whose nickel property has more iron than nickel sulfide – its grade is just 0.12% nickel. The company managed to raise $1.25 million last month and its market cap has risen with the price of nickel, and currently sits around $20 million.

Giga Metals (TSX-V: GIGA) has a low-grade sulfide nickel deposit and trades at a healthy $23 million market cap versus Inomin’s <$1 million. The company’s Turnagain project is certainly impressive, with a measured and indicated resource of 1.073 billion tonnes containing 5.2 billion pounds nickel and 327 million pounds cobalt.

But Turnagain is in the middle of nowhere in north-central BC, with little to no infrastructure. The only access is by light aircraft and power must be supplied by diesel generators. The capex to develop this mine would be huge.

Beyond Giga Metals’ Turnagain nickel deposit in northern BC, Beaver has similarities to the giant Dumont nickel project in Quebec in terms of mineralization, with similar mineralogy and grades. Even the mineralization trends in the same northwest direction.

Inomin’s cost of developing a mine and for a major to operate it would be significantly less than its competitors. About 90% of the Beaver and Lynx properties are on Crown land, ensuring no land rights issues, and accessible via paved and forestry roads. Williams Lake, a major center for mining suppliers close by.

Importantly, the project is only six kilometers from a power line that runs to the Gibraltar mine, put in courtesy of the BC government. The cost of electricity in BC is low – about 6 cents a kilowatt-hour versus 15 to 20 cents/kwh in other jurisdictions.

Conclusion

It’s often said that grade is king. While ounces per ton win the hearts (and wallets) of gold investors, with base metals a low-grade project with mass, scalability and decades LOM (Life of Mine) beats the high-grade but small-scale charlatans.

To interest a major, a nickel junior must have five elements: size, grade, scalability, longevity and infrastructure.

Inomin’s Beaver and Lynx properties have all that in spades. Not only are the grades as good or slightly better than its neighbouring copper porphyries, my initial tonnage calculation shows a massive blanket of nickel sulfides with cobalt credits – and the latter is nothing to sneeze at, at 14 to16 bucks a pound.

It’s exciting to imagine the prospect of developing a long-lived nickel-cobalt mine on the strength of just one of MINE’s projects – the Beaver – a 32-square-kilometer patch of mineralization on par with some of BC’s most prolific copper-gold and copper-molybdenum mines in the same geological neighborhood.

And then, add the bluesky exploration potential of Lynx!

These are early days with respect to Inomin’s development/ exploration of their nickel sulphide project but the company already has an advanced nickel system at Beaver, proven by drilling, and a similar but potentially much larger nickel opportunity at Lynx.

Given the scale of the Beaver-Lynx project – in a tier one jurisdiction with excellent infrastructure – it’s my opinion the project should eventually attract the interest of big players.

Inomin Mines Inc.

TSX.V:MINE, Cdn$0.04 2019.11.22

Shares Outstanding: 16,584,264m

Market cap: Cdn$663,370.00

MINE website

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions.

Richard does not own shares of Inomin Mines (TSX.V:MINE). MINE is an advertiser on his site.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.