Impacts of BC’s late-summer drought being felt province-wide – Richard Mills

2022.10.18

Although British Columbia experienced an unusually cold and wet spring, delaying the start of summer until the beginning of July, Mother Nature has made up for it with a blast of heat that has enveloped the province in drought and kept the forest fires burning well into the fall.

And as we saw last November with the “atmospheric rivers” that brought catastrophic flooding to southern British Columbia, our problems don’t end with the extinction of the fires.

Between wildfires, landslides from melting glaciers, flooding, and freak winter storms resulting from a breakdown of the northern polar vortex, British Columbians appear to be on the front lines of climate change.

Warming, fires & drought

Unusually warm weather and forest fires burning into October are two signs that something isn’t right with the climate in British Columbia.

Temperatures are five to eight degrees above normal, and much of the province is experiencing drought conditions — extremely unusual for this time of year.

Victoria, Comox and Abbotsford all had their warmest Septembers on record. For example the mean temperature for Abbotsford last month was 17.9 degrees C, compared to the normal 15.3.

Global News reported that August 2022 was the warmest ever in BC, and the province’s second-hottest month.

The average temperature in August, 20.3 Celsius, just missed the record-breaking monthly average of 20.6 C, set in July, 1958.

Where I live in north-central BC, the climate has changed dramatically since I moved herein the mid-1980s. Back then, it was common for winter temperatures to plummet into the minus 40s. It was cold enough to kill off all the insect infestations we get now, such as the pine beetle and the spruce beetle, that chew their way through large stands of trees. I recall one Christmas when the temperature + the wind chill hit minus 80!

Nowadays the only time we get -40 is with the wind chill. Another thing that’s different is the so-called “Pineapple Express,” a spell of warm, wet weather that usually arrives in January. These systems are common in southern BC but were an irregular occurrence up north. Now every January the weather warms enough to melt a significant amount of snow, we get rain, and when the cold returns end up with a sheet of ice covering everything.

Generally, our springs come sooner than before, and fall comes later.

Tree rings are another sign of a warming climate. A log house on my property was built, around 1920, with +200-year-old pine trees. You can tell the climate back then by the tight spacing of the tree rings on the logs, which indicate long winters and short growing seasons. More recently cut logs have much more widely spaced rings, indicating short winters and much longer growing seasons.

The provincial government confirms with facts, what we’ve experienced here, anecdotally. The province has warmed an average of 1.4 C per century from 1900 to 2013, higher than the global average of 0.85 C. The northern regions have warmed 1.6 to 2.0 C, twice the global average. Most of the warming has occurred during winter.

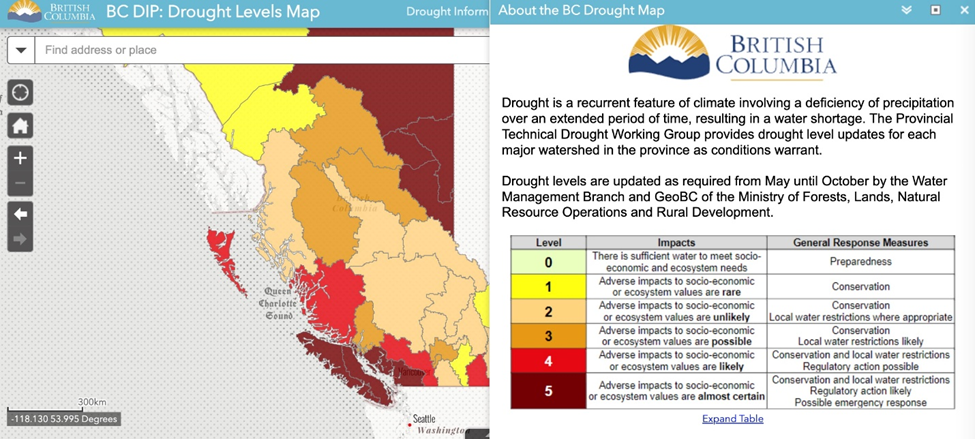

On Oct. 1 the Forest Service warned that Vancouver Island, the inner South Coast and northeastern BC reached the second-most severe level of drought, Level 4, on the five-point rating scale.

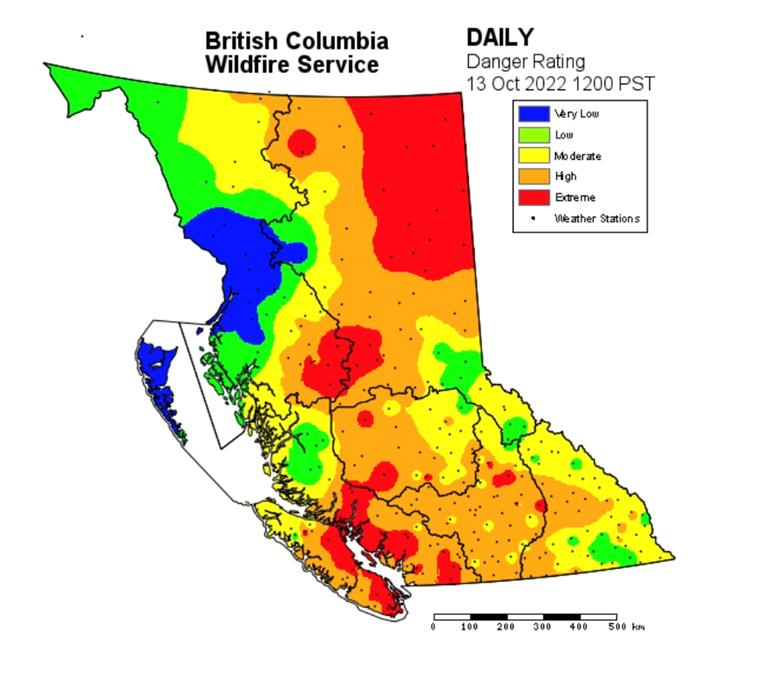

At this level, conditions are “extremely dry and adverse effects to socio-economic or ecosystem values are likely,” the government said in a statement. Residents under drought levels 3 and 4 are asked to reduce their water usage whenever possible. The map below, screen shot taken on Friday, Oct. 14, shows Vancouver Island, the Lower Mainland and Sunshine Coast, and a large swath of northeastern BC, have moved to Level 5 in brown, where “adverse impacts to socio-economic or ecosystem values are almost certain.”

According to The Vancouver Sun, If conservation measures do not achieve sufficient results and drought conditions worsen, the B.C. government said temporary protection orders under the Water Sustainability Act may be issued to water licensees to avoid significant or irreversible harm to aquatic ecosystems…

Climate change is contributing to more droughts and water shortages around the world, and experts say it is connected not just to global warming, but also biodiversity and nature loss, and pollution and waste, according to the UN.

A recent report from the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification found that the number and duration of droughts has increased by almost a third in the last two decades.

Meteorologists say the South Coast stands out as particularly dry, with weather stations in Victoria reporting their first- and second-driest months on record. Vancouver recorded just seven millimeters of rain in September, making it the seventh-driest September and well under the monthly average of nearly 60 mm.

The ongoing drought on the Sunshine Coast has drained the water supply to historic lows. Without imminent precipitation, the region will run out of water in early November. The Sunshine Coast Regional District has been at Stage 4 water restrictions since Aug. 31, banning all outdoor use, and an emergency operations centre was established to respond to the crisis, CBC News said.

Lower water levels are forcing the province’s main utility, BC Hydro, to adjust its operations. In a press release issued Oct. 13, Hydro stated, while there is adequate water at its larger facilities and it can easily meet the demand for power, inflows into reservoirs at some of its smaller facilities in the Lower Mainland and on Vancouver Island are at near or recording-breaking [low] levels.

As a result, the company said it has been taking proactive steps to protect downstream fish habitat, such as holding back water in July and August at some facilities, to help ensure there is enough water storage for late summer and early fall for salmon spawning.

It notes while the dry conditions have had an impact on BC Hydro’s watersheds, several unregulated watersheds have fared worse, with rivers drying up and thousands of fish dying.

The most significant operational impacts are on the Puntledge and Campbell rivers on Vancouver Island, as well as the Coquitlam River and Ruskin/Stave in the Lower Mainland. The Campbell River broke a 53-year-old record low in September, whereas in the Lower Mainland, inflows since the beginning of September are in the bottom three periods, historically.

Hydro says the lower water levels have not yet affected the continued delivery of power.

While storms could start rolling in soon thanks to a jet stream over Western Canada, the rain they bring probably won’t be historic. “As we look ahead to the second half of October and early November, it appears that the current pattern will break down for a while, but it is unlikely that we will see a complete or long-lasting reversal of the pattern that we have seen since late September,” states The Weather Network’s long-range forecast by meteorologist Doug Gillham.

As the summer lingers on, the B.C. Wildfire Service has warned this year’s “very unique fire season” isn’t over yet. The season started late due to a delayed snowmelt, then transitioned into hot, dry conditions by July that continue to persist into October, which is usually the fourth-rainiest month of the year in BC.

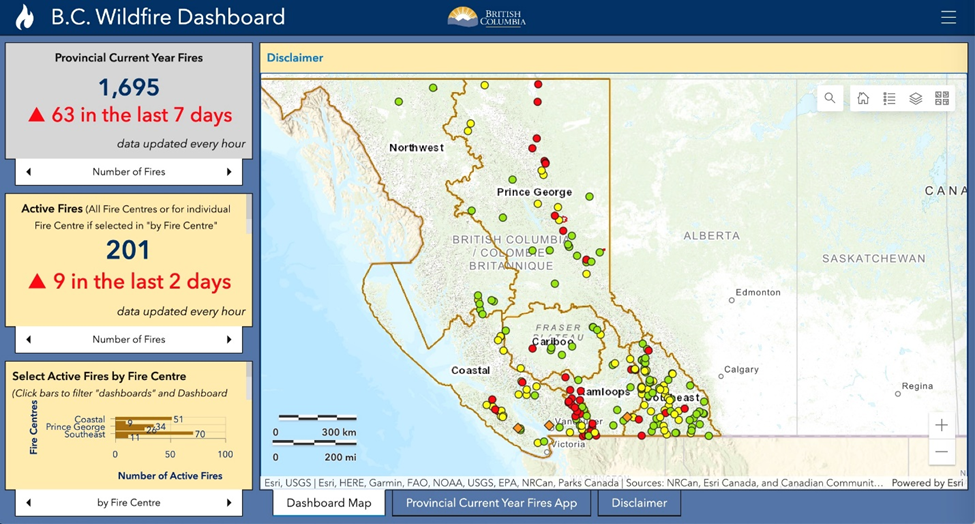

These are ideal conditions for wildfires. As of Friday, Oct. 14, there were 201 active fires burning in BC, with nine sparked in the last two days.

Unfortunately, the effects of climate change in BC go far beyond droughts, forest fires and water shortages.

Salmon & trees

Both Atlantic and Pacific salmon are cold-water fish, meaning they do best at temperatures in the mid-teens. Warmer water holds less oxygen, making it harder for fish to breathe. The heat also makes it challenging to swim and can stress them when they are trying to get to spawning grounds. Some don’t survive to spawn, while others produce less healthy offspring.

On top of extreme heat, climate change is causing drier conditions that affect river flows and temperatures. For example shrinking glaciers and smaller snowpacks reduce the amount and depth of water, causing them to heat up more quickly.

People are also taking too much groundwater that would otherwise seep into streams. Deforestation from wildfires, pests like the mountain pine beetle, and clearcut logging, have all increased erosion and landslides, which have destroyed or threaten to wreck spawning grounds and impede spawning salmon from continuing their lifecycle.

Last week, the Globe and Mail printed a picture of thousands of dead salmon, lying in a dried-out creek bed near Bella Bella, on British Columbia’s central coast.

According to William Housty, a conservation manager with the Heiltsuk First Nation, “We’ve had such a dry summer and fall. Salmon are returning to spawn, but water levels continue to drop, and they are running out of space and oxygen.”

This summer’s drought isn’t a one-off affecting salmon; the problem has been happening for a long time and it’s persistent. The changes involve both higher water temperatures and lower water levels. While some salmon are being stranded as streams dry up, in other cases the fish are waiting in the ocean or in a lake for their spawning stream to appear. All that waiting causes problems.

“These adult migrants are on a one-way ticket to death. Once they’ve initiated their migrations to leave the oceans, it’s a one-way ticket. They can’t turn around. They have to keep going,” Scott Hinch, a professor of fisheries conservation at UBC’s department of forest and conservation sciences, told The Narwhal. “They can hold off for maybe a week or two, but their biological clocks are ticking … They are going to die, potentially unspawned, if they can’t get to their spawning streams.”

When the rains do arrive, the severe drought increases the risk of flooding, which also destroys critical salmon habitats, like happened during last November’s “atmospheric rivers”. (the parched landscape has a diminished capacity for absorbing water)

Trees are another victim of drought. Richard Hebda, an ecologist who has studied the impacts of climate change on ecosystems, predicted 30 years ago that western red cedars would struggle in a warmer, drier climate. A photo in The Narwhal piece shows red cedars in Carmanah-Walbran provincial park turning yellow and orange from drought, during a time of year they should remain green.

Hebda predicts red cedars will disappear from eastern Vancouver Island by 2050.

Landslides

In June 2019, early runs of Stuart sockeye and chinook salmon were obliterated by a massive landslide. DFO officials estimated the blockage preventing the fish from swimming up-river resulted in 89% of early Stuart and 99% of early sockeye being lost.

The Big Bar incident occurred in a remote and rugged canyon along the Fraser River north of Lillooet, when over 85,000 meters of rock sheared off from a 125-meter-high cliff and fell into the river. The large blocks of rock created a five-meter waterfall that trapped migrating salmon below the slide.

On Nov. 28, 2020, a landslide in a remote British Columbia valley sent 18 million cubic meters of rock hurtling down the side of a mountain.

The slide at Bute Inlet, about 160 km from Vancouver, was so large, when it hit Elliot Creek, it caused a 100-meter-high tsunami that wiped out 10 kilometers of salmon habitat and was detected as far away as Germany, Japan and Australia.

“Imagine a landslide with a mass equal to all of the automobiles in Canada travelling with a velocity of about 140 kilometres an hour when it runs into a large lake,” Marten Geertsema, lead author of a study on the slide, and adjunct professor at the University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC), described it in an interview with Global News.

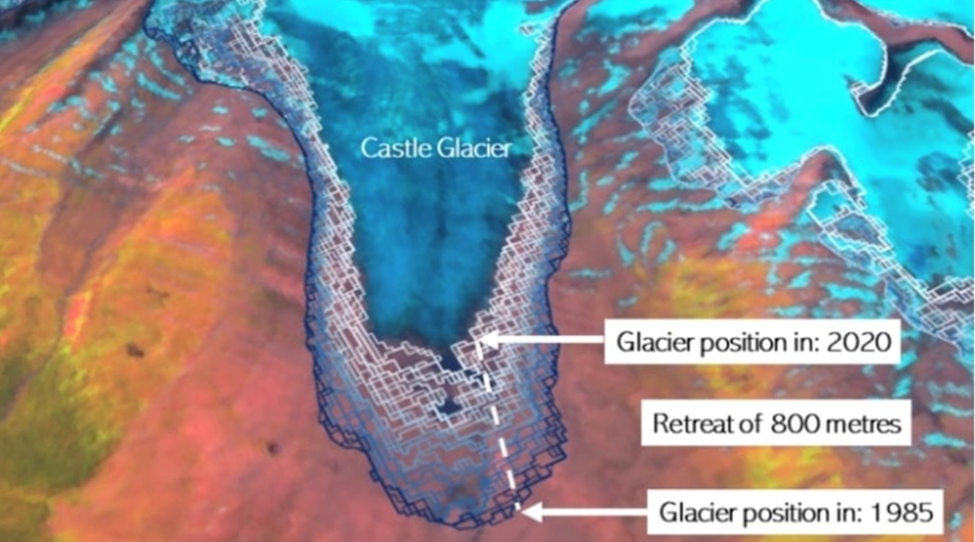

While it’s impossible to say precisely what caused the slide, scientists know that glaciers, which once blanketed and held the slopes together, are melting rapidly due to climate change, leaving the sides of the mountains loose and exposed. A rainstorm or unusually wet conditions can become the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

The incident serves as a warning to other parts of BC. Glaciers in central BC are melting faster than almost anywhere else in the world. According to a study published earlier this year by geologists at UNBC, the rate of glacial retreat between 2010 and 2020 was seven times faster than between 1984 and 2010. Smaller glaciers on Vancouver Island are disappearing 32 times faster, in the same period.

Glacial melt

Most of the world’s fresh water is contained within glaciers or hard-packed snow that falls in the mountains and becomes freshet in the spring, filling creeks, rivers, lakes, rechargeable aquifers and reservoirs. Mountain glaciers sustain large numbers of people, who collect the annual freshet that flows from higher elevations and is funneled into creeks.

We know from several years of measurements, that mountain glaciers are in retreat.

Over the last few decades, almost all the world’s glaciers have shrunk and the rate of decline is accelerating. An expert on glacier dynamics, associate professor Jeff Kavanaugh at the University of Alberta, expects that between 60 and 80% of the ice volume in BC and Alberta will be lost by 2100.

As for how melting glaciers affect our water supply, Prof. Kavanaugh says glaciers keep our rivers flowing when other water sources, like snow melt, dry up. He predicts the next few decades will be marked by high flows in our glacial rivers, but after that, “it will start to fall off a cliff. How much water is flowing through the river as a function of that time of year is going to start changing remarkably.”

Personally I see the latter as “nature’s cover-up”. People can easily be fooled into thinking that streams and rivers are full because there is plenty of snowpack, when in fact it’s because glaciers are melting. The cover-up may last several years, it takes a long time for glaciers to completely melt, but once they do, all that will be left to re-charge rivers, lakes and reservoirs, is the annual snowpack, that will become smaller and smaller as the Earth warms. Glacial melt is happening on a global scale, clarifying the enormity of the problem.

Conclusion

Like all countries and regions, British Columbia is subject to the whims of changing weather and climate. Mother Nature cares nothing about who you are, or where you live. If all the elements are present, natural disasters such as droughts, wildfires, landslides and glacier-melt flooding, are likely to occur, with alarming frequency.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. Policymakers are wasting their time trying to stop global warming. The Earth will continue to warm until it starts to cool, following natural cycles that have continued for thousands of years.

The better course of action is to prepare for warmer temperatures, by planting drought-resistant crops; figuring out how to get water to drought-affected areas so that human and animal/ plant populations are minimally affected; relocating low-elevation housing and public buildings that are in danger of being inundated by rising sea and river water; moving low-lying infrastructure like sewage treatment plants to higher ground; and carrying out storm mitigation measures, such as re-building older dikes and levies, and hardening highway bridges and overpasses to make them more resistant to extreme weather (100-year storms are now happening every 50 or 25 years).

A 2020 study by the Insurance Bureau of Canada, calculates that local governments nation-wide need to spend $5.3 billion a year to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Unfortunately, here in BC we seem to be moving in the opposite direction of climate change mitigation.

The provincial government’s (both the BC Liberals and the NDP) foolish pursuit of liquefied natural gas is only going to make global temperature rise worse, as millions of tonnes of greenhouse gases, most of it extremely-potent, 86-times-worse-than-CO2 methane, is spewed into the atmosphere through fracking, pipeline leaks, and the liquefaction process.

The argument that LNG is better for the environment than coal, and by selling it to Asia we are improving the climate, is ridiculous. The Chinese, the Indians, and Germany, by the way, continue to rely on coal for energy and if they do build natural gas plants, they will be just as dirty, if not dirtier, than what LNG Canada is planning.

Droughts have negative impacts not only on fresh water supplies and crops, but on salmon that need the creeks to be high enough for them to swim up to spawn. As salmon runs decline, the favorite food of killer whales is becoming harder to find. When you combine that with an increasing number of commercial vessels, whose loud engines make it difficult for the animals to find food and mates, it’s no wonder that orcas are on the Endangered Species List.

We are supposedly a green province, yet we are going balls to the wall to frack more natural gas to feed at least 22 compressor plants up and down the BC coast, so that we can ship an annual 350 LNG tankers to Asia, by transiting the natural habitat of the endangered southern-resident (and northern-resident) killer whales. Even if the whales can find enough salmon to eat, with that many tankers plowing through their waters with the noise level of a rock concert, will they be able to find mates? It seems a perfect storm is brewing for their extinction sooner rather than later.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.