Huge copper supply deficit looming – Richard Mills

2025.03.29

Like silver and gold, traders are also front-running copper ahead of potential tariffs on the metal come April 2, although Citi Bank thinks a copper tariff won’t come into effect until the fourth quarter.

On March 19 Bloomberg reported between 100,000 and 150,000 tons of refined copper is expected to arrive in the US in coming weeks. If the full volume arrives in March, it would beat the record of 136,951 tons set in January 2022:

Commodities traders including Trafigura Group, Glencore Plc and Gunvor Group are redirecting large volumes of metal earmarked for Asia to the U.S. The quantity is so big that traders are booking additional warehousing space in New Orleans and Baltimore to accommodate the shipments.

In February Trump launched a probe into potential new tariffs on copper, saying they would help rebuild US production.

Whatever the results of the probe, the reality is that the United States is in no position to set up a protectionist barrier against copper imports. The reason is simple: the US relies too much on foreign copper supplies and building new mines in the US takes up to 20 years.

Imports account for about half of US copper usage, up from just 10% in 1995. Chile, Peru and Canada account for the majority of imported copper. The United States though is a relatively small market for Chile and Peru. Most of their exports go to China.

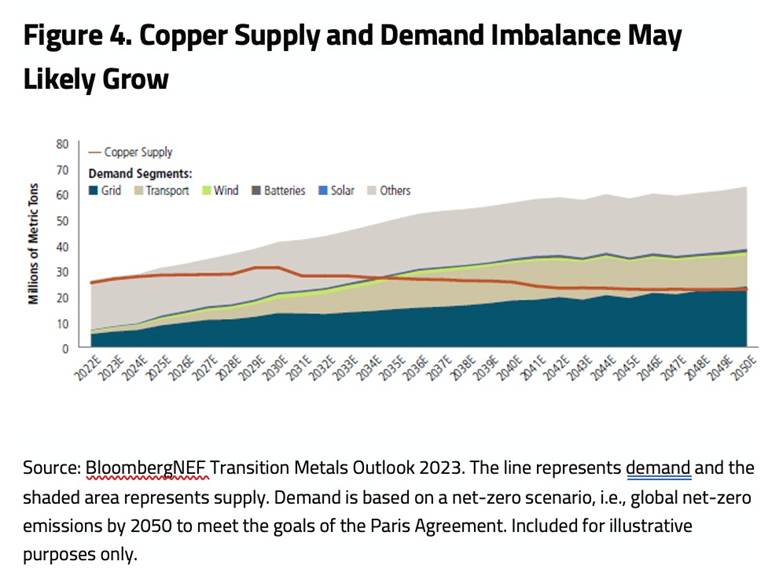

S&P Global produced a report in 2022 projecting that copper demand will double from about 25 million tonnes in 2022 to 50Mt by 2035. The doubling of the global demand for copper in just 10 years is expected to result in large shortfalls — something we at AOTH have been warning about for years.

Forbes argues that if Trump is fixated on luring manufacturing to the States by throwing up tariffs, he should exempt imports of raw materials especially critical minerals like copper:

Whereas tariffs on imported finished goods may provide incentives to produce in the United States, tariffs on production inputs are strong disincentives to do so because they raise U.S. manufacturing costs…

The “mineral of electrification” is essential to manufacturing and construction in traditional and emerging U.S. industries, alike. Electrical uses of copper, which include power generation and transmission; wiring in offices, hotels, and other structures; telecommunications; and electrical and electronic products account for about 75% of total copper demand. But copper is also used intensively in transportation equipment and infrastructure, industrial machinery, and a growing number of products. Lower copper prices enable greater profitability among U.S. manufacturers, and more investment.

Aside from making manufacturing more expensive, copper tariffs are a foolish policy because the mining, refining and forging stages of the supply chain are so integrated. According to Forbes, The U.S. portion of the industry employs over 65,000 workers, generates $77 billion in output, and depends on access to imports of refined copper to succeed.

The Hill agrees with Forbes that the supply chain for copper is too closely meshed for tariffs to work. Author Marc L. Bush writes that “Trump is right to target copper as a national priority, but he’s going about it the wrong way.”

Like semiconductors and pharmaceuticals [and autos — Rick], copper is the product of a complex supply chain. The four key stages include mining, smelting and refining, semi-fabricating and manufacturing final goods. The U.S. has different challenges at each stage, but tariffs are not the solution to any of them.

Bush identifies the problems with bringing a mine online, noting the US ranks second-last globally in terms of required lead times — 29 years, just ahead of Zambia’s 34 years. Potential new copper mines face permitting challenges. For example, development of Rio Tinto and BHP’s massive Resolution copper mine in Arizona is on hold, facing opposition from native Americans.

Second, the US only has two operating copper smelters, one secondary smelter and 17 refineries. Decoupling from China, which controls 97% of global copper smelting and refining capacity, is a fool’s errand.

“Trump’s proposed copper tariffs will put America last, not first,” Bush asserts.

Even with tariffs, American copper buyers have little choice but to keep buying imported metal given that the US consumes twice as much as it produces. (Bloomberg)

Mining Weekly concurs that The US industrial sector will have the most to lose from potential US tariffs on copper, analysts say, with costs seen rising significantly during what would be a lengthy process of reviving domestic mining and refining of the metal.

US copper production dropped 3% last year from 2023, following an 11% decline that year.

The Northern Miner quotes the former CEO of Codelco — the world’s largest copper mining company — saying that US tariffs on copper will only serve to drive up prices because domestic producers can’t make up the shortfall.

“Implementing such a measure as part of protectionist policies to boost domestic copper production would not be beneficial for the U.S.,” Marcos Lima said in February.

“The only thing that will happen is that the price of copper in the United States will rise,” Lima told the ‘Miner via email. “It’s impossible for the country to increase its production levels overnight.”

Bloomberg argues that not only will tariffs raise copper prices in the United States, hurting end users, they will also exacerbate the looming global copper shortage.

Reportedly, American buyers are already looking to source more copper from Chile and Peru, because copper from Mexican and Canadian mines could get diverted to Europe to avoid paying US tariffs.

Less raw copper entering the US means less copper will be shipped to China for refining:

Tariffs could cause China to refine less copper — to the tune of 10,000 to 20,000 tons a month within the first three months. That’s in a global market that Goldman already expected to be facing a 180,000-ton deficit this year.

Copper smashed another record on Wednesday, March 27, with the most traded contract on the COMEX reaching $5.37 a pound or $11,840 a tonne. Traders predicted at a Financial Times commodities summit in Switzerland that the metal could reach at least $12,000 a tonne this year as supply concerns flare up globally. (Mining.com)

COMEX copper prices are now up 27% since the start of the year, while the LME price is about 14% higher — incentivizing traders and producers to keep moving copper to New York.

Looming copper shortage

Demand

Global copper consumption has increased steadily in recent years and currently sits at around 26 million tonnes. 2023’s 26.5 million tonnes broke a record going back to 2010, according to Statista. From 2010 to 2023, refined copper usage increased by 7 million tonnes.

Wall Street commodities investment firm Goehring & Rozencwajg quoted data from the World Bureau of Metal Statistics confirming that global copper demand remains robust, outpacing supply. Through the first eight months of 2024, the bureau said, copper demand grew by nearly 4%, with standout gains driven by non-OECD nations Malaysia, Taiwan, Vietnam and Brazil, which saw consumption grow by 8.3%.

The shift to renewable energy and electric transportation, accelerated by AI and decarbonization policies, is fueling a massive surge in global copper demand, states a recent report by Sprott.

Increasing investments in clean technologies like electric vehicles, renewable energy and battery storage should cause copper demand to climb steadily, and challenge global supply chains to meet this demand.

The report cites figures from the International Energy Agency (IEA), such as global copper consumption growing from 25.9 million tonnes in 2023 to 32.6Mt by 2035, a 26% increase. Clean tech copper usage is expected to rise by 81%, from 6.4Mt in 2023 to 11.5Mt in 2035.

The IEA expects the copper needs from electricity networks to grow from 4.1Mt in 2023 to 6.2Mt by 2035, an increase of 49%. Copper demand for solar panels is expected to rise by 43% and for wind power by 38% over the same period.

The fastest-growing area, though, is grid battery storage, where copper demand is expected to surge by 557% to 2035 as the need for energy storage increases, Sprott writes.

Copper demand for EVs is a close second, with a projected rise of 555% from 396,000 tonnes in 2023 to 2.6Mt by 2035, with EVs accounting for 8% of global copper consumption by that year.

BHP foresees global copper demand increasing by 70% to reach 50 million tonnes annually by 2050.

Supply

On the supply side, BHP points to the average copper mine grade decreasing by around 40% since 1991. The next decade should see between one-third and one-half of the global copper supply facing grade decline and aging challenges. Existing mines will produce around 15% less copper in 2035 than in 2024, states the company.

“Most of the high-grade stuff’s already been mined,” says Mike McKibben, an associate professor emeritus of geology at University of California, Riverside, quoted recently by NPR. “So, we have to go after increasingly lower grade material” that costs more to mine and process, he says.

Shon Hiatt, a business professor at the University of Southern California, said, “It’s projected that in the next 20 years, we will need as much copper as all the copper that has ever been produced up to this date.”

Mining Technology reports that global copper production in 2024 was poised to reach a new high of 22.9Mt, a 3.2% increase from 2023. A confirmation is provided by the US Geological Survey, which showed mine production in 2024 of 23Mt, 600,000 tonnes more than 2023.

The supply increase is being driven by expansions at key mining operations in several countries including Chile — the top producer — the DRC, Russia, Zambia and China.

Mining Technology notes Chile was set to see a substantial bump in 2024 output thanks to the expansion of Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca mine — 252,200 tonnes compared to just 62,700t in 2023, a 303% increase.

GlobalData forecasts a CAGR of 4.2% for global copper production, reaching 29.3Mt by 2030. Note from above, however, the IEA predicts global copper consumption reaching 32.6Mt by 2035, creating a potential shortfall of 3.3Mt.

Deficit

Full-year 2024 copper supply figures recently became available from the International Copper Study Group. In its January report, the ICSG shows a slight increase in world copper mine production, 22.884 million tonnes in 2024 versus 22.384Mt in 2023.

Last year saw a surplus of refined copper production, 301,000 tonnes, determined by subtracting world refined copper usage of 27.332Mt from world refined copper production of 27.634Mt.

However, that could change as early as this year.

According to Swiss bank UBS, via EV Magazine, the current copper surplus will swing to a deficit exceeding 200,000 tonnes in 2025.

What could cause the copper market to fall into a large deficit hole from which it would be very difficult to climb out of? There are several factors.

Last year S&P Global commissioned a report that blamed the shortfall on underinvestment in new exploration and mines due to the industry’s focus on short-term returns (NPR)

It noted the copper industry faces pressures from the need to decarbonize itself; political instability in many countries which mines are located; and reputational damage from its history of safety and environmental failures. The latter means the industry is now under greater scrutiny from regulators and community groups.

The firm predicts copper supply will be unable to keep up with demand from as early as 2025; demand could double to 50Mt by 2035.

In a piece by the International Energy Forum (IEF), Goldman Sachs found that regulatory approvals for new mines are on a downward trend, having fallen to the lowest level in 15 years, which is particularly disturbing since it can take 10 to 20 years to approve and develop a mine in North America.

Another factor behind depleting copper supply is a lack of new discoveries.

According to Crux Investor, citing S&P Global Commodity Insights, Despite a 12% increase in exploration budgets in 2023, the industry has seen only four major discoveries in the past five years (2019-2023), totaling a mere 4.2 million metric tons (MMt) of copper. This marks a significant downturn in the frequency and size of major discoveries compared to previous decades.

What’s behind this trend? Crux says companies are increasingly focused on brownfield (past-producing) assets rather than engaging in greenfield exploration that could yield new, large-scale discoveries. Early-stage exploration budgets have dropped to a record low of 28%, compared to the 50-60% allocation that was typical in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Crux says the copper market is heading towards a significant supply-demand imbalance, making the following supporting points:

- A refined copper deficit is projected to begin in 2027

- The concentrate market is currently in deficit and expected to remain so for the next five years

- Mine supply is forecast to peak in 2029

- A potential concentrate deficit of 2.2Mt is expected by 2032

The International Energy Agency believes existing mines and projects under construction will only meet 80% of copper needs by 2030.

“There’s this growing consensus that demands fueled by the energy transition is going to outstrip supply and that’s why analysts are now saying we’re simply not going to have enough of it,” says Pippa Stevens, markets reporter, in a 2024 CNBC video on the coming copper shortage.

The video says it is very difficult for existing mines to even maintain current levels of production. To keep up with demand, the industry is faced with a number of obstacles including a shortage of mine workers, navigating regulatory hurdles and dealing with pushback from local stakeholders.

Moreover, most of the “low-hanging fruit” has already been mined.

“High-grade economic copper resources are not abundant, these things aren’t all over the place, you have to go find them,” said Chris LaFemina, global metals and mining analyst at Jefferies.

Inflation and the high costs associated with building a new mine are also deterrents.

“It’s so capital intensive, you need to invest billions upfront for a payout that might take 10 or 15 years to come in the future and by that time who knows what the economic landscape, the political landscape will look like and so it’s hard for investors to give the green light for that,” says Stevens.

The video concludes that demand may already be starting to outweigh supply: the amount of copper needed in the 28 years between 2022 and 2050 will exceed the amount consumed between 1900 and 2021.

While copper is abundant globally, only a fraction can be extracted cost effectively at today’s prices and with current technology.

Sprott said in a 2024 ‘Insights’ report that Chile and Peru, the top copper-producing countries, are grappling with labor strikes and protests, compounded by declining ore grades. Russia, ranked seventh in copper production, faces an expected decline due to the ongoing war in Ukraine. Despite efforts by miners to ramp up production, many analysts anticipate a widening supply imbalance.

In Chile, Glencore recently declared “force majeure” on copper shipments from its Altonorte smelter due to an issue affecting the plant’s furnace. Force majeure is a term describing temporary circumstances preventing mining companies from meeting contractual obligations. Bloomberg said The incident adds to recent outages at smelters and refineries in Asia, which could serve to tighten the metal market even further amid a worldwide dash to front-run potential tariffs by US President Donald Trump.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Share Your Insights and Join the Conversation!

When participating in the comments section, please be considerate and respectful to others. Share your insights and opinions thoughtfully, avoiding personal attacks or offensive language. Strive to provide accurate and reliable information by double-checking facts before posting. Constructive discussions help everyone learn and make better decisions. Thank you for contributing positively to our community!

3 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

#Copper #tariffs #forcemajeureoncoppershipments

I truly a;preciate your information

thank you

Rick