How global warming will drive conflict and worsen inequality – Richard Mills

2024.01.31

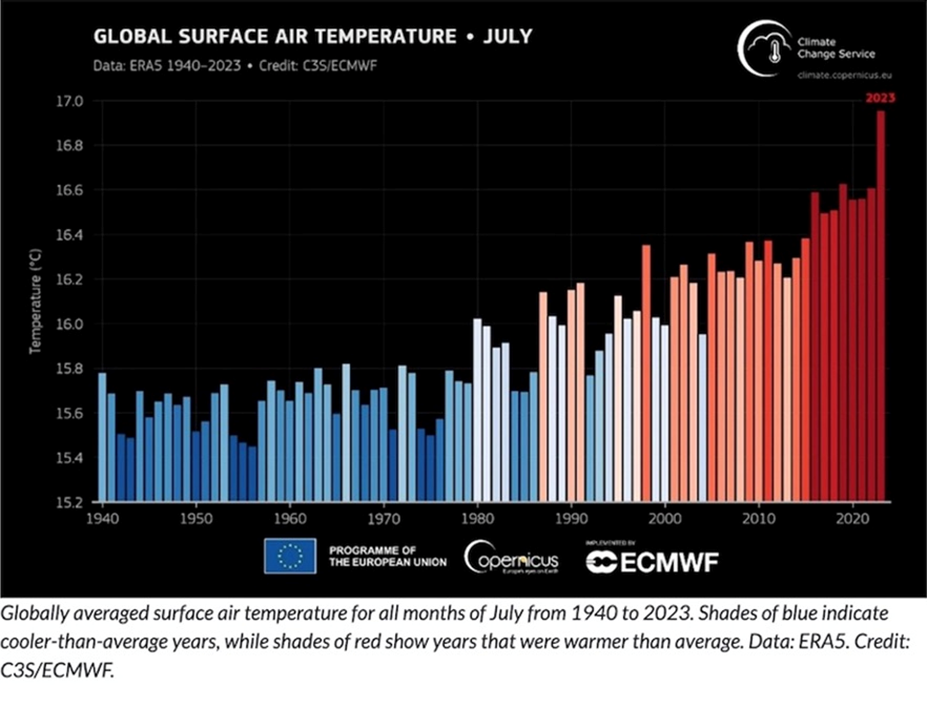

The last eight years have been the hottest on record, with 2023 the warmest ever.

October 2023 hit a world heat record. According to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), October’s previous 2019 record was broken by 0.4C, “which is a huge margin,” said C3S Deputy Director Samantha Burgess.

Last year’s average temperature was about 1.4C higher than the pre-industrial era; early estimates suggest 2024 will be between 1.3 and 1.6 degrees higher.

Bloomberg notes that almost every month in 2023 was warmer than the 1991-2020 average. After El Nino started, monthly heat records were shattered in June, July, August, September, October and November. July was the warmest month ever observed and July 6 was the hottest day on record.

If you thought 2023 was hot, scientists are warning that temperatures may climb even higher in 2024, due to a combination of global warming and El Nino.

The current El Nino is considered strong, and could peak in the coming weeks. If the same thing happens this year as in 2016, the last El Nino, it could mean record warmth could surge even higher. A Washington Post article states that the abnormal sea surface warmth and storms it brings to the central and eastern Pacific Ocean, leads to drought in other parts of the world including southeast Asia and southern Africa.

“That sets the stage for higher-than-normal temperatures over land,” perhaps peaking around February,” said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. “I expect this to be the case at least for the first 6 months of 2024.”

According to Britain’s Met Office, a lingering El Nino in 2024 could be enough to push average planetary temperatures more than 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels — considered the point of no return for runaway global warming.

As the trend is set for more warmth on a planetary scale, we need to think about what this means for society — both economically, in terms of the effects on agriculture, food production, water, energy and commodity prices; and socio-politically, meaning how climate change could exacerbate existing inequality, and drive conflicts over scarce resources as well as mass migrations from the hardest-hit areas.

Agriculture

Climate change has a major impact on agricultural commodities that are affected by droughts and flooding. Paraguay was hit by a 2021 drought that badly damaged crop yields and caused navigation problems in the Paraguay-Panama waterway, pushing up the costs of transporting grains for export. Dry conditions often cause forest fires that can ruin crops and kill livestock.

Flooding and saltwater intrusion are also threats to farming, especially in coastal areas vulnerable to rising sea levels. Projections by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have levels increasing by a foot by 2050, threatening to inundate cities including Miami and New York.

The November, 2021 flooding in southern British Columbia caused up to $5 billion in uninsured losses and $675 million in insured losses, according to a damage estimate caused by extreme weather that year, put out by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

The CCPA report said total damages ranged from $10.6 billion to $17 billion, including uninsured wildfire losses of $501 million.

The flood event caused by a series of “atmospheric rivers” reportedly caused the deaths of 628,000 chickens, 420 dairy cattle and 12,000 pigs.

Droughts are impacting food production in Canada and the United States, lowering crop yields, and causing ranchers to cull part of their herds. The war between Russia and Ukraine led to record-high fertilizer prices in 2022.

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would on average reduce global yields of wheat by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

A 2021 study showed more than a fifth of global food output growth has been lost to climate change since the 1960s, putting an estimated 34 million people on the brink of famine.

Water

Availability of fresh water is also a growing concern.

In 2020, the federal government declared a water shortage on the Colorado River for the first time, triggering mandatory water consumption cuts.

Lake Mead, America’s largest manmade reservoir, and a source of water for millions, in 2022 fell to an unprecedented low.

If too much groundwater is pumped out from coastal aquifers, saltwater may flow into them causing contamination. Many coastal aquifers — the Biscayne Aquifer near Miami and the New Jersey Coastal Plain aquifer for example — have problems with saltwater intrusion. The phenomenon can also be caused by rising sea levels and storm surges.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), via Reuters, the seas lapping US coasts are expected to rise at a faster pace than in the past 100 years; a one-foot rise by 2050 threatens coastal cities including New York, Boston and Miami.

Salt water from the Bay of Bangladesh has penetrated over 100 kilometers inland, due to sea levels rising higher than elsewhere, thereby increasing the risk of water contamination and hypertension caused by drinking high-salinity water. High river and soil salinity in Bangladesh is also predicted to reduce rice crop yields, affect the productivity of fisheries, crack road surfaces, and increase poverty.

Energy

Hydroelectric dams and nuclear power plants are both highly dependent on water supplies to generate energy. It’s ironic that these “green” sources of electricity could themselves become victims to rising temperatures that dry up their water sources.

According to Forbes, global energy agencies forecast a doubling of global capacity by 2050. Yet due to the level of climate change that is already baked in, drought-driven embargos on hydropower’s water fuel are likely to become more frequent and more widespread in the coming decades.

For example, during the summer of 2022, Europe and China endured historic droughts that lowered rivers and drained reservoirs. Sichuan province relies on hydro for 80% of its electricity and the extended drought cut generation in half, leading to tens of thousands of commercial customers having to shut down for 10 days in August.

Droughts also lowered the amount of electricity generated by dams in Italy, Austria, Spain and Portugal.

In the southwestern US, dams on the Colorado River provide electricity to 5 million people, but water levels in the reservoirs have been falling for decades. Via Forbes, the Bureau of Reclamation reported there is a nearly one in three chance that reservoir levels will fall so low that the Glen Canyon Dam will stop generating electricity, this year.

Further downstream, diminished annual generation at the Hoover Dam has started a conversation about a potential “deadpool” situation.

A 2015 drought in Zambia, which depends on hydro from nearly all of its electricity, caused national power generation to decline by 40%, resulting in rolling blackouts.

Forbes states, This rising risk is not limited to Africa. A recent study in Nature Climate Change found that, even under the most optimistic climate scenario, more than 60% of existing hydropower projects are in “regions where considerable declines in streamflow are projected” by 2050, rising to 74% of projects with greater warming…

Meanwhile, a quarter of all planned hydropower dams are in regions with medium to very high levels of water scarcity risk.

Nuclear power plants are also feeling the effects of diminished river levels. A researcher at the University of Washington found that nuclear and other power plants will see a 4 to 16% drop in production between 2031 and 2060 due to climate-induced drought and heat. (InsideClimate News)

In July 2012, power generation from US nuclear plants, which normally supply 20% of the nation’s power, fell to 93% of capacity. Among the facilities affected were the Vermont Yankee plant, First Energy Corp’s Perry 1 reactor in Ohio, and the Braidwood nuclear plant near Chicago.

An Associated Press analysis quoted by NBC News states that of the United States’ 104 nuclear reactors, 24 are in areas experiencing the most severe droughts. Submerged intake pipes draw billions of gallons of water used for cooling and condensing steam after it has turned the plant’s turbines.

For nuclear power plants, it isn’t only the danger of water running low, but of water getting too hot. Water is normally used to cool the reactors before it is released into the river. But overheating can threaten fish and other wildlife.

In 2021, Wired reported that, amidst a heat wave that killed hundreds and sparked wildfires across Western Europe, Electricite de France (EDF) powered down reactors along the Rhone and Garonne rivers. The temporary shutdowns were due to river water becoming too warm. The 2021 cuts, combined with malfunctions and maintenance on other reactors, reduced France’s nuclear output by nearly 50%.

EDF also curtailed production at a nuclear plant during a heat wave last summer that triggered water restrictions.

When a critical dam in Ukraine was destroyed by some type of explosion attributed to the Russia-Ukraine war, within a matter of days the water level in the reservoir dropped by 20 feet, imperiling the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station.

Extreme heat

When temperatures are rising so fast that extreme heat becomes a common occurrence in several parts of the world including our own (Western Canada), let’s consider what this means for human health.

Get ready for extreme heat and its effects on crops, lives

People are generally comfortable living and working in temperatures up to about 80 degrees Fahrenheit. The heat index is what the temperature feels like when relative humidity is combined with relative humidity. Between 80 and 90 degrees F, fatigue is possible with prolonged exposure and/or physical activity. From 90 to 103, heat stroke, heat cramps or heat exhaustion are possible. The danger zone is entered at temperatures between 103 and 124, with extreme danger happening when it gets to 125 F (51 Celsius) or higher.

In fact, our current heat measurements may be underestimating the dangers of extreme heat to the human body. Meteorologists are therefore turning to the “wet bulb globe temperature” for a more accurate reading.

Basically a more nuanced version of the heat index, the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) takes into account not only the air temp and humidity, but the wind speed, sun angle and solar radiation levels.

Between 80 and 88 degrees Fahrenheit WBGT, working in the sun for more than 45 minutes put the body under serious stress. About 88 WBGT, the window of safety closes to 20 minutes. Above 90, being active in the heat becomes dangerous after 15 minutes, and reaches a point in the 90s where you shouldn’t be doing anything outside.

The latter point is important. According to Popular Science, This is not an issue of simply not exercising or working outside. Wet bulb temperatures this high can kill people who are simply sitting around doing nothing, if they lack access to air conditioning and water.

This is because, above a certain WBGT, the human body loses the ability to cool itself down. The body’s normal cooling mechanism, the way it sheds heat, is by sweating. The upper level of sweaty skin is about 95 WBGT; beyond that, skin loses the ability to carry heat from the body and evaporate it through sweat. Wet bulb temperatures above 95 are therefore extremely dangerous, and sustained temperatures above 98 are considered fatal. The body literally cooks to death from within.

It was previously thought that wet bulb temperatures very rarely exceeded 91 degrees F, but a 2020 study quoted by Popular Science found that this point has been crossed many times. Among the regions that have experienced this kind of heat, are South Asia, the coastal Middle East, and coastal southwestern North America.

As an illustration of how dangerous this level of heat is, consider: the heat wave in Russia in 2010 and those across Europe in 2003 had wet bulb temperatures below 83 F. Around 55,000 people died in Russia and 35,000 were killed in Europe during these heat waves.

Imagine how many people, many of whom lack access to fresh water and air conditioning, could be killed if wet bulb temperatures push into the 90s, which is entirely possible the way global warming is going?

Inequality

Inequality is one of the most volatile aspects of contemporary society, and it is getting worse. As the gap between the haves and the have-nots widens, and the middle class shrinks, the chances of social upheaval increase.

History tells us that a state’s failure to redress rampant inequality can result in bloody revolution.

The Gini coefficient is the way economists measure the income gap. It is calculated by assessing the relative share of national income received by proportions of the population. A society with perfect equality would have a Gini coefficient of 0, whereas a nation with one individual hoarding every penny of its wealth would have a Gini of 1.

Inequality tends to be greater in developing countries than developed ones. The exception is the United States, which in 2021 had a Gini coefficient of 0.494, 1.2% higher than 0.488 a year earlier. The US Gini is quite a bit higher than Denmark’s, which stood at 0.28 in 2019, and France, whose Gini was 0.32 in 2018, according to Census Bureau data.

The Conversation points out that the inequality picture is even worse when looking beyond income (what people earn) to wealth (what they own). In the United States, the richest 1% of Americans own 34.9% of the country’s wealth, while average Americans in the bottom half had USD$12,065. The disparity is greater in the US than in other industrial nations, such as Germany, where the richest 1% own 18.6% of the wealth, or in the UK, where they own 22.6%.

According to the 2022 World Inequality Report, the richest 1% now hold nearly 76% of the world’s wealth, while the bottom 50% own just 2%.

A global movement of people are demanding they get what they think they deserve. While the conditions in each country experiencing social change are diverse, there are common themes.

“While thousands of miles apart, protests have begun for similar reasons in several countries, and some have taken inspiration from each other on how to organize and advance their goals,” reads a 2019 analysis by the BBC.

The British broadcaster finds inequality, corruption, the need for political freedom and climate change are ideas that bind protesters together. The catalysts for social change, though, have been the passage of seemingly minor laws.

In Lebanon, people rose up over the government’s Orwellian decision to tax What’s App calls. Chileans donned balaclavas and dodged tear gas over a proposed increase in transit fares.

Watch this video by CNBC to understand five key drivers of inequality that are widening the gap between the rich and the poor:

- The digital revolution, which creates huge opportunities for those with the skills and education to take advantage, but eliminates “middle skill” jobs like clerical and manufacturing positions that once produced middle-class incomes for those without college degrees;

- Globalization, involving competition from economies like China, combined with reduced trade barriers, have further reduced prospects for those without advanced skills. This was dramatically accelerated by China’s acceptance into the World Trade Organization in 2001. Around one in three American manufacturing jobs existent in 2000, were gone by the end of the Great Recession in 2010;

- Superstar tech firms like Apple, Amazon, Uber and Facebook are market disruptors that generate huge global revenues. Their CEOs, like Tesla’s Elon mush, the richest man in the world, make obscene packets and feel they are entitled to much more, dramatically accelerating the CEO-to-worker compensation ratio;

- The percentage of the workforce represented by labor unions has halved since the 1980s, shrinking their power to extract concessions from management. The government has not increased the minimum wage to keep pace with inflation.

- Certain government decisions have rewarded the wealthy, such as the $1.5 trillion Trump administration tax cuts in 2017, and college admissions procedures that open doors to their children above others.

Climate change and inequality

What does inequality have to do with climate change? Well, global warming is almost certainly going to make it worse.

In 2021, a World Bank report estimated that an addition 68 to 135 million people will be pushed into poverty because of climate change.

This is because in the poorest economies, a large portion of the population depends on activities most affected by global warming, including agriculture, forestry and fisheries.

It should also be noted that the richest countries represent only 16% of the world population but almost 40% of CO2 emissions. The two categories of the poorest countries in the World Bank classification account for nearly 60% of the world’s population, but for less than 15% of emissions.

An increase of 1.5°C would expose 245 million people to a new or aggravated water shortage; this number becomes 490 million at +2°C, states the report.

Resource nationalism

Resource nationalism is the tendency of people and governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over their natural resources.

‘Power to the People’ and mining

Developing countries have seen the benefits of foreign companies coming in to extract their natural resource endowment, in the form of jobs and higher wages for their often-impoverished citizens, and government revenues through taxes, royalties or dividends.

Yet, for countries such as Ecuador and Venezuela, it’s not enough. Their governments were elected to help relieve the plight of the poor, and they intend to make good.

Miners are easy targets because mining is a long-term investment and especially capital intensive. Mines are also immobile, so mining companies are at the mercy of the countries in which they operate. Outright seizure of assets often happens using the twin excuses of historical injustice and contractual misdeeds. There is no compensation offered and no recourse.

Countries are getting creative in how to bleed away miners’ profits. Governments have gone beyond taxation in getting more out of the mining sector with a wave of requirements such as mandated beneficiation (where ore is processed locally rather than exported raw), export restrictions and increased state ownership of mines.

This is becoming a serious problem in the case of in-demand metals such as copper, graphite and silver, needed for the new green economy, and critical minerals like rare earths, mined by countries with an itchy resource nationalism finger.

The most recent example is the Panamanian government’s court-ordered closure of the Cobre Panama copper mine, stripping 400,000 annual tonnes from global copper supply.

As the demand by Western countries for these raw materials grows, the connection between social unrest and mining is tightening.

A crisis of unaffordability

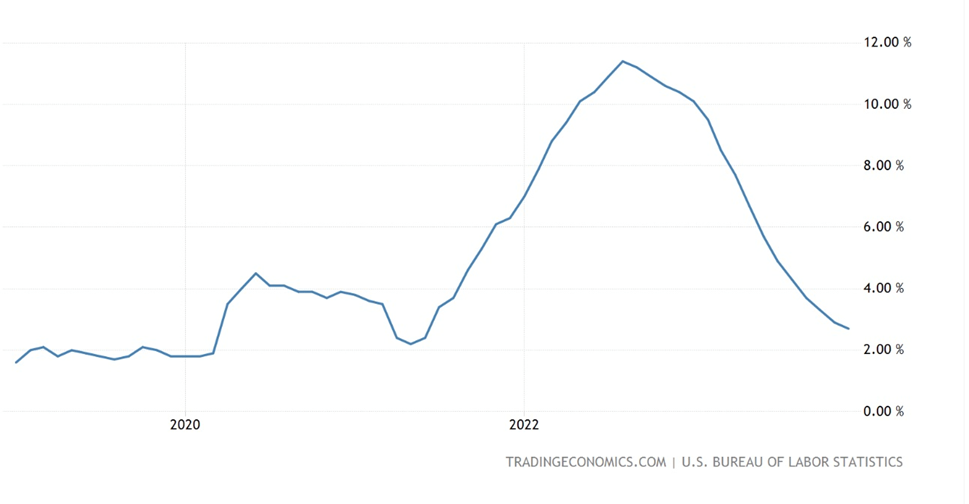

The impacts of droughts and floods, climate change and covid-19, have all been passed up the food supply chain to the consumer, who is seeing double-digit inflation in some products such as meat.

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia, a major oil and gas producer, and the world’s largest exporter of wheat, in 2022 added to higher grocery bills, and record gasoline prices.

While food inflation in Canada and the United States has come down, prices are still higher than they were before the pandemic which started in early 2020.

Oxford Economics sees global food prices remaining 25% higher than during the pre-pandemic decade.

In a previous article we gave reasons why food prices will remain high. They include:

- Labor shortages. Canadian food producers are dealing with a labor shortage, and are passing down higher costs to consumers A report from RBC’s Climate Action Institute projects that Canada’s agriculture sector is expected to be short some 24,000 general farm, nursery and greenhouse workers over the next decade. The RBC report projects that, in the short term, Canada will need to attract 30,000 permanent immigrants to establish their own farms or take over existing ones to maintain the agricultural sector’s output. The Canadian food and beverage industry will need 142,000 new people or almost 50% of the current workforce between 2023 and 2030. The U.S. Department of Agriculture says labor is among the biggest expenses US fruit and vegetable growers face, and farm wages are rising at a faster rate than non-farm wages.

- Greedflation. Another explanation for getting larger grocery bills, is that grocers have been using inflation as an excuse to hike prices and pad their own profit margins — a practice they call “greedflation”. Between 2019 and 2022, the profits of Canada’s three largest grocers went up by $1.2 billion, representing a 50% increase over the four-year period, a study found.

- War in Ukraine. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine might be the single biggest catalyst leading to the high food prices we’re seeing today. Many emerging market countries rely on food imported from Ukraine and Russia – known as ‘the breadbasket of Europe’ due to the region’s abundance of grains like wheat, barley, corn and soybeans. For wheat, Russia and Ukraine are the largest and seventh largest exporters respectively. Within about a week of Russia crossing into Ukraine on February 24, 2022, prices for grains like soybeans and some vegetable oils spiked 50% to 60%. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Food Price Index, global food prices eased substantially in 2023. However, with the war showing no signs of stopping, who knows how long the inflationary pressures on our food supply could drag on.

- Climate change. The impact of climate change on food supply and prices over a longer horizon also cannot be understated. Global warming is influencing weather patterns, causing heat waves, heavy rainfall, and droughts, making it difficult to grow crops in many parts of the world year after year. Last year in the western United States, droughts and wildfires led to lower-than-average crop yields. According to the World Bank, about 80% of the global population most at risk from crop failures and hunger from climate change are in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, where farming families are disproportionately poor and vulnerable. A severe drought caused by an El Nino weather pattern or climate change can push millions more people into poverty. Transport issues are further compounding food security concerns. Water levels on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers in 2023 fell for a second straight year, raising the prospect of shipping problems on crucial freight routes.

People are getting mad, and it isn’t only rising food prices.

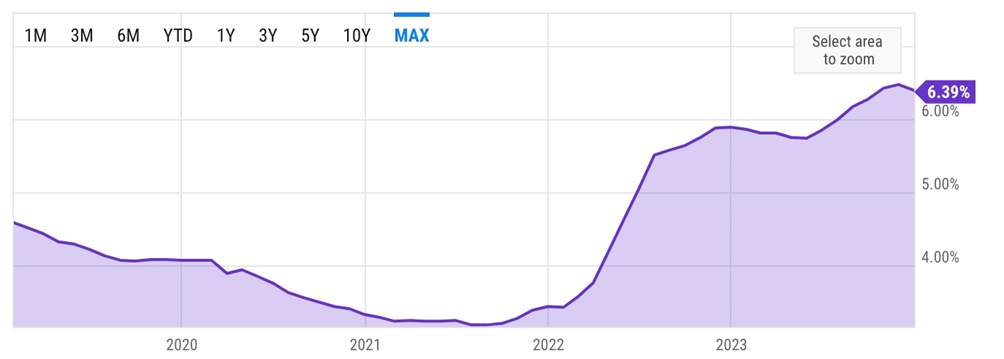

Inflation in the United States and Canada in 2022 hit levels last seen in 1982. Admittedly, prices have eased. But in the early ‘80s, at least you could afford to buy a house, even with interest rates in the double digits. For many North Americans, that is no longer the case. Home inflation is running rampant, and rents are higher than ever. The cost of mortgaging a home has climbed in tandem with central bank interest rate hikes. In the US, the average interest rate on a mortgage amortized over 30 years is currently 6.9%. In Canada, interest on the average 5-year mortgage is 6.3%.

Consumers everywhere are getting squeezed on housing costs, food, persistent inflation and a loss of purchasing power. (One dollar in 1860 was equivalent to $27.80 in 2015. The dollar has lost 90% of its purchasing power since 1950. Read Wages slaves vs gold owners)

US single family home prices. Source: Trading Economics

Right-ward shift

There is evidence that rising inequality is eroding trust in democracy and fostering the spread of authoritarian and nativist movements.

The Guardian observes that right-wing political movements and the rise of populism over the last few years have their roots in the financial crisis of 2008-09. Not only did the Great Recession result in significant job losses and millions of Americans losing their homes from the sub-prime mortgage crisis, it also “stripped the sheen off global capitalism”:

In the US alone, the great recession erased about $8tn in household stock-market wealth and $6tn in home value. From 2003 to 2013, inflation-adjusted net wealth for a typical household fell 36%, from $87,992 to $56,335, while the net worth of wealthy households rose by 14%. Workers without college degrees and low-income Americans were especially hard hit.

Partisanship

As a nation, the US is more divided than it has been since the Vietnam War protests of the 1960s.

In one corner are Republicans, predominantly white, conservative, religious, defending law and order, and wanting limited immigration. In the opposite corner Democrats are against almost everything the GOP stand for: the goal is inclusivity, defunding the police, righting racial wrongs by electing and appointing more blacks and Hispanics to key positions; multilateralism and globalization abroad; and at home, debt “out the wazoo”. Throwing money at problems is seen not only as a way to help those less fortunate, but to redress social and economic inequality through spending and taxation.

Things aren’t much better in Canada. The Trudeau Liberals came to power in 2015 on promises of national unity and transparency. Nine year later, the country is racked by divisions. According to a March, 2023 op-ed in The National Post, The news is filled with reports of election interference from China, we have a government that is consistently hiding information from the public, ministers who have been the subject of a slew of ethics investigations; and a country that seems more divided than it has in a long time. We’re in a mess.

A poll taken last July found that 60% of respondents agreed that Trudeau has been divisive during his time in office, with 40% feeling the country has become worse off since his election.

Rise of authoritarianism

This year will be a test for democracy, as more than half of the world’s 6 billion eligible voters go to the polls. Along with the US presidential and congressional elections in November, in 2024 there will be elections in India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Russia, Mexico, and likely Britain and Canada.

It will be interesting to see who voters choose. A recent Globe and Mail article reminds us that The past dozen years have seen a rapid rise of leaders and prominent candidates who have threatened or outright abolished many of those foundations of democracy – despite continuing to hold elections. As such, 2024′s torrent of ballots is being anticipated by informed observers not with celebratory toasts, but with deep anxiety and ominous foreboding…

The article quotes the International institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, which in its 2023 report, described 2022 as “the sixth consecutive year in which more countries have experienced net declines in democratic processes than net improvements.”

Examples of democratic reversal include a wave of military coups, often with apparent Russian backing, that swept across Africa in 2022 and 2023, turning erstwhile democracies including Gabon, Niger, Burkina Faso, Sudan, Guinea, Chad and Mali into military autocracies. The military has similarly seized control, at least until February’s election, in Pakistan, and effectively controls Egypt…

March’s “election” in Russia will be a coronation of President Vladimir Putin, who veteran Globe and Mail reporter Doug Saunders notes has killed or imprisoned all credible opponents. Mexico’s president has vowed to shut down democratic oversight agencies and end freedom of information laws, ahead of the June election.

The article observes that the biggest reversals of democracy have not come from outrights coups, shifts to dictatorship, or revolutions. Rather, they are instances of “democratic backsliding”, meaning things like centralization of power by presidents and prime ministers, manipulation of the elections and courts, and use of police and the military to maintain a grip on power.

The number of “electoral autocracies” has risen from 35 in 1978 to 56 in 2022. Saunders describes these as countries with elections but with one party or leader more or less permanently in power, such as Russia. They are now the second most common type of regime, with the most common being “non-liberal democracies”, which are countries with elections but without the institutions and rights of democracy.

Conflict

Taken to extremes, inequality causes social upheaval, and often, violent revolution. China, Russia and France are among the countries that experienced bloody worker or peasant-led insurrections.

We only have to look at Chile to see this dynamic in action. In 2019, over a million people turned out to show their frustration at widening inequality and what many saw as the government’s attack on the poor. The trigger was a seemingly innocuous hike in transit fares.

A state of emergency was declared and armed forces mobilized on the streets of Santiago for the first time in nearly 30 years. Chile, the world’s largest producer of copper and with the most lithium reserves, used to be considered among the most stable and business-friendly Latin American nations.

Protests have since spread to Argentina, Peru and Ecuador.

It may surprise readers to learn that US history is littered with examples of civil unrest. Americans have taken to the streets and rioted over a seemingly endless list of grievances, including racism, sexism, workers’ rights, immigration, housing, the draft, food, beer, wars, and most recently, Black Lives Matter — a combination of perceived racial injustice and police brutality/ racial profiling.

We all know that race is a defining cleavage of American society dating back to the days of slavery. We would therefore expect a lot of civil unrest to be racially motivated. More surprising is how many of these protests were over food, worker’s rights and global capitalism.

Examples include:

Flour Riot, 1837 — In New York City, hungry workers plundered storerooms filled with sacks of hoarded flour, after commodity prices skyrocketed over the winter of 1836-7, fueled by foreign investment and two successive years of wheat crop failures.

Richmond Bread Riot, 1863 — Food deprivation during the American Civil War was the cause of this, the largest civil disturbance in the Confederacy during the war, in Richmond, Virginia, on April 2, 1863.

Draft Riot, 1863 — The same year, four days of violence erupted in New York City, resulting from worker discontent surrounding the inequities of conscription.

Haymarket Riot, 1866 — The Haymarket Riot was a violent confrontation between police and labor protesters over workers’ rights.

Seattle General Strike, 1919 — More than 65,00 workers paralyzed the city during a five-day work stoppage lasting from Feb 6-11.

Ford Hunger March, 1932 — On March 7, during the depths of the Depression, unemployed autoworkers marched from Detroit to Dearborn, Michigan. In a confrontation with police, four workers were shot dead and one later died of his injuries.

Levittown Gas Riot, 1979 — Thousands rioted in Levittown, Pennsylvania over increases to gasoline prices, resulting in 198 arrests, with 44 police and 200 rioters injured. Gas stations were damaged and cars set on fire.

WTO Meeting, 1999 — Also referred to as the Battle of Seattle, the 1999 Seattle WTO protests were a series of protests surrounding the World Trade Organization’s Ministerial Conference, held at the Washington State Convention and Trade Center. Negotiations were quickly overshadowed by massive street protests involving at least 40,000 protesters, more than any previous meeting associated with globalization.

Occupy Wall Street, 2011 — The movement against economic inequality, greed, corruption and the undue influence of corporations on government, was initiated by Canadian anti-consumerist magazine AdBusters. The OWS slogan “We are the 99%” refers to income inequality between the wealthiest 1% and the rest of the US population.

As the planet continues to warm, and populations are forced to migrate from worst-hit areas, like coastal cities, to inland areas, there will be increased competition for resources, whether it be housing, jobs, food, or on a macro level, raw materials such as copper, nickel and lithium needed for electrification.

In 2019, US News reported on a research paper which found that intensifying climate change will likely increase the future risk of violent armed conflict within countries.

The researchers agreed with us, at AOTH, that mass displacements of people forced to leave areas that become inhospitable, increase the possibilities for conflict.

According to a University of Notre Dame index, countries most vulnerable to climate change are in the global south. African countries are particularly susceptible. More than 1.2 million people were killed in civil conflict across the continent between 1989 and 2018 — a period which saw annual rainfall fall well below average, the US News article states.

In a speech, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres called climate change a “crisis multiplier”. He said the risk of conflict is exacerbated in counties where climate change leads to drought or reduced harvests or destroys critical infrastructure, such as Afghanistan.

“The forced movement of larger numbers of people around the world will clearly increase the potential for conflict and insecurity,” Guterres said.

A more recent article by Al Jazeera says that climate change is already causing human rights emergencies around the world. It quotes U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Turk, who last September pointed to recent examples of the “environmental horror that is our global planetary crisis”, including in Basra, Iraq, where “drought, searing heat, extreme pollution and fast-depleting supplies of freshwater are creating barren landscapes of rubble and dust”.

“This spiralling damage is a human rights emergency for Iraq and many other countries,” Turk told the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva on Monday.

“Climate change is pushing millions of people into famine. It is destroying hopes, opportunities, homes and lives. In recent months, urgent warnings have become lethal realities again and again all around the world,” he said.

“We do not need more warnings. The dystopian future is already here. We need urgent action now.”

Conclusion

Climate change is making it more difficult to irrigate fields and pastures. Droughts and floods are ruining crops or reducing yields, forcing some farmers into bankruptcy. Many grocery items that exploded in price due to covid-related supply disruptions, bad weather, the Russo-Ukrainian war, or a combination of the three, have yet to come down.

Higher food, energy and housing prices tie into a growing crisis of affordability.

It all adds up to a perfect storm that, if nothing changes, will imo lead to a breaking point, when people have nothing left to lose and revolution is seen as the only means of forcing social and economic change.

The effects of climate change are starting to be felt in the global south, where droughts, lack of freshwater, searing heat and pollution are forcing people to pull up stakes and migrate to better locations. These “climate refugees” are knocking on the doors of Western countries including the United States and Canada.

Global warming is making existing armed conflicts in the southern hemisphere worse. How long before these civil wars spill over into the northern hemisphere and richer nations are forced to confront the twin realities of climate refugees, and conflict within our own borders, as competition for scarce resources intensifies?

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.