How global warming and El Niño will affect commodities – Richard Mills

2023.08.31

There’s no getting around it: our planet is warming at a terrifying pace, marked by extreme weather events that now seem like normal occurrences.

This summer, we continue to see intense storms, scorching heat waves and prolonged droughts hitting different parts of the world, culminating in what was the hottest month ever in July 2023. A study by Germany’s Leipzig University found that the month had 23 consecutive days of record global temperatures, surpassing the previous record set four years ago by a “considerable margin” (i.e. 0.2 degree Celsius).

During that month, record-breaking heat waves were seen in several spots around the world, notably in the US Southwest, Mexico, China and around the Mediterranean. The records, says the Scientific American journal, are primarily linked to overall rising global temperatures from the excess heat trapped in the atmosphere by humans burning fossil fuels.

It followed what was already the hottest June on record. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) database indicated that through the first half of 2023, we’ve already experienced the third-warmest year to date (behind 2016 and 2020).

Another analysis published by the World Weather Attribution group found that this year’s heat waves, particularly those in North America and Europe, were “virtually impossible” without climate change, which refers to the broader range of changes that are happening to our planet, including global warming.

The study also found that the heat wave in China was 50 times more likely to occur in our current warmer world. All three heat waves were hotter than they would have been without the boost from global warming, it said.

El Niño’s Influence

What’s really different about this year’s hot weather is that the planet is hit with a double whammy of both human-caused global warming and the natural phenomenon known as El Niño.

El Niño — meaning “the little boy” in Spanish — is characterized by the unusual warming of the surface waters in the tropical central and eastern Pacific Ocean. This climate pattern is cyclical, taking place once every 2-7 on average.

In June, scientists at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) officially announced the arrival of this recurring weather-changing phenomenon, noting that El Niño conditions are present and are expected to gradually strengthen into the winter months.

“We do expect the El Niño to at least continue through the northern hemisphere winter. There’s a 90% chance or greater of that,” NOAA meteorologist Matthew Rosencrans told NPR back in July.

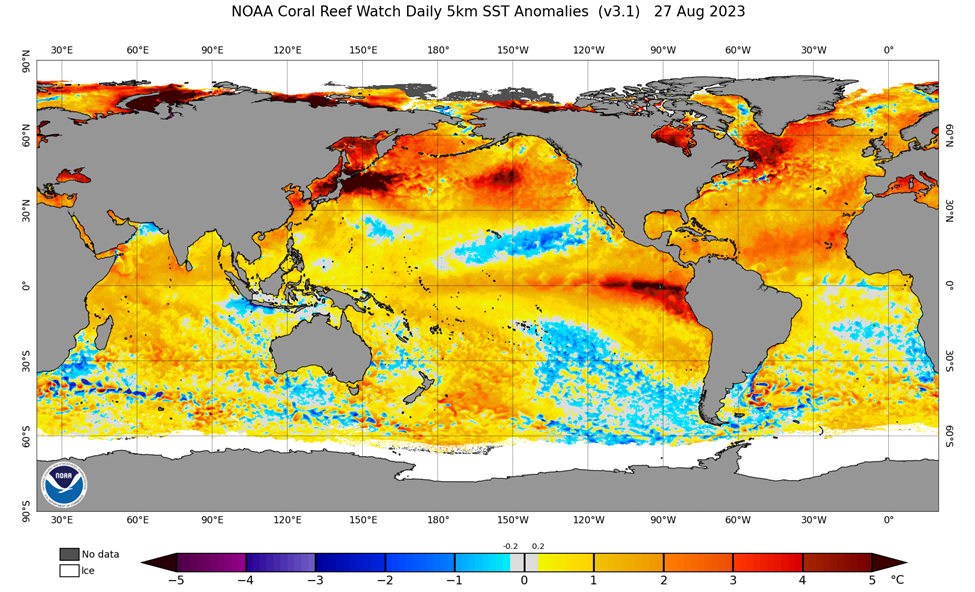

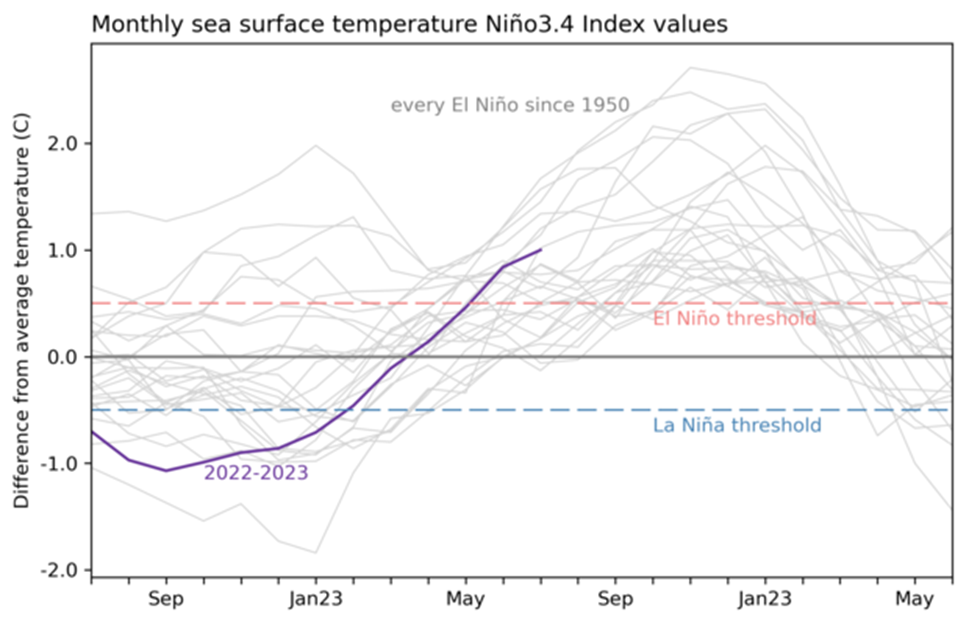

To track El Niño’s progress, scientists at the NOAA measure sea surface temperatures in the east-central tropical Pacific Ocean. An El Niño event is typically declared when sea surface temperatures in the tropical eastern Pacific rise to at least 0.5C above the long-term average.

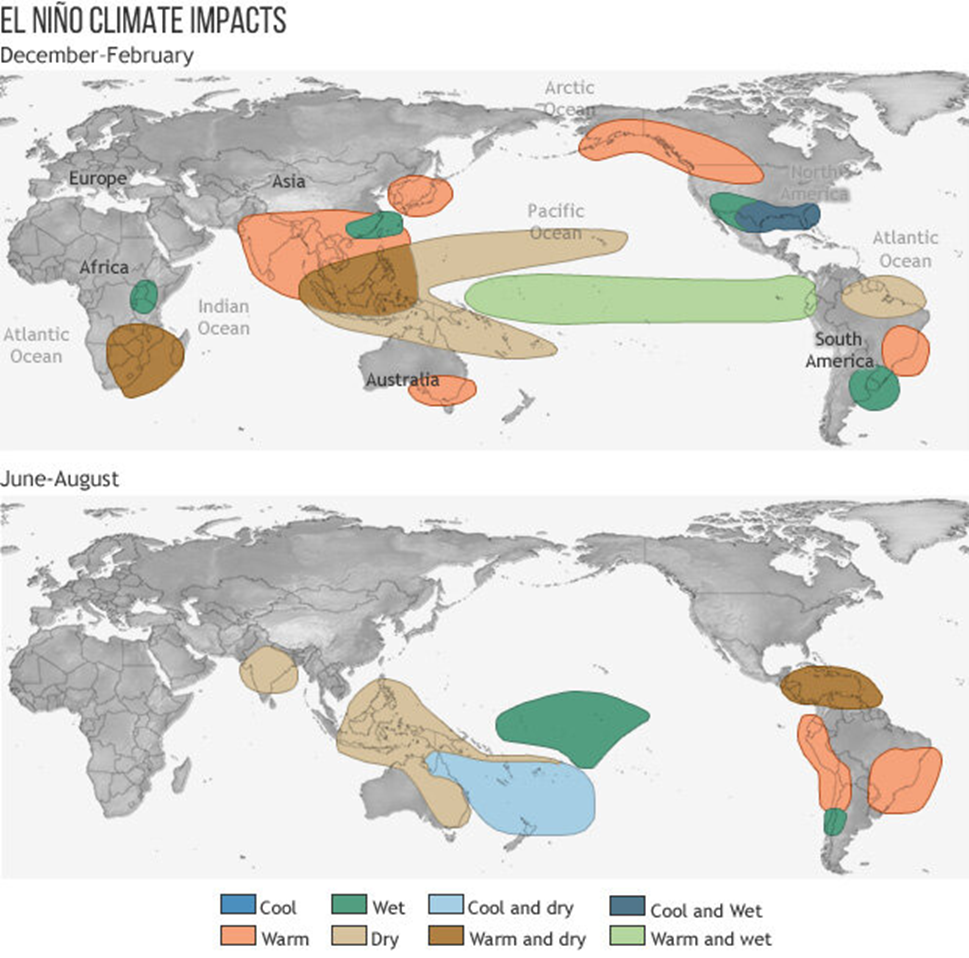

It’s been well-established that warmer or colder-than-average ocean temperatures have an influence on weather. According to the NOAA, El Niño causes the Pacific jet stream to move south and spread further east. During winter, this leads to wetter conditions than usual in the southern US and warmer and drier conditions in the north.

NOAA also stated that El Nino’s impacts on the climate can also extend far beyond the Pacific Ocean.

Its strongest impacts are usually felt during the Northern Hemisphere’s winter and early spring, bringing more rain and storms across the southern US, southeastern South America, the Horn of Africa and eastern Asia. In other parts of the world, such as southeastern Africa and Indonesia, El Niño leads to drier conditions and may increase the risk of drought.

“Depending on its strength, El Nino can cause a range of impacts, such as increasing the risk of heavy rainfall and droughts in certain locations around the world,” said Michelle L’Heureux, climate scientist at the Climate Prediction Center, part of the NOAA”s National Weather Service.

“Climate change can exacerbate or mitigate certain impacts related to El Nino. For example, El Nino could lead to new records for temperatures, particularly in areas that already experience above-average temperatures during El Nino.” This year’s record-breaking heat in the southern US serves as an example.

“The oceans have been warming steadily but we are now seeing record temperatures which is certainly alarming given we are expecting El Niño to strengthen,” Ellen Bartow-Gillies, a climate scientist at NOAA, told The Guardian. “That will undoubtedly have an impact on the rest of the world.”

In an article by The Guardian, it calls this event the biggest natural influence on year-to-year weather and adds a further spurt of warmth to an already overheating world.

The last major El Niño from 2014 to 2016 led to each of those years successively breaking the global temperature record, and 2016 remains the hottest year ever recorded (at 2.6 degrees C above average).

More Hot Weather

However, that record is also in jeopardy. Scientists have warned that this year’s El Niño could “substantially exceed” those recorded during the last strong event in early 2016.

The latest NOAA update shows a more than 95% chance the event will last through to February 2024, with far-reaching climate impacts.

“El Niño is anticipated to continue through the Northern Hemisphere winter,” a NOAA staff wrote in the update. “Our global climate models are predicting that the warmer-than-average Pacific ocean conditions will not only last through the winter, but continue to increase.”

This is based on both the sea surface temperatures as well as atmospheric conditions recorded by the NOAA, which according to the administration, are consistent with a long-lasting El Niño.

“El Niño is a coupled phenomenon, meaning the changes we see in the ocean surface temperatures must be matched by changes in the atmospheric patterns above the tropical Pacific,” the update said. More rain and clouds over the central Pacific, as well as weak pressure in the east and reduced trade wind activity in the west, suggest “the system is engaged and that these conditions will last through the winter,” it added.

Through the month of July, sea surface temperatures in the east-central tropical Pacific exceeded the long-term average for 1991 to 2020 by 1 degree Celsius, according to the NOAA. Temperatures from May to July — a three-month average called the Oceanic Niño Index — were also 0.8 C higher than usual and marked the second warmer-than-average Oceanic Niño Index in a row.

“We need to see five consecutive three-month averages above this threshold before these periods will be considered a historical ‘El Niño episode,'” the NOAA post said. “Two is a good start.” There is “a good chance” the Oceanic Niño Index will match or exceed the threshold for a “strong” El Niño.

L’Heureux of the Climate Prediction Center, who coordinates NOAA’s El Niño forecast updates, believes there is a 30% chance that this year’s will end up just as mighty as the one in 2016.

Impact on Shipping Routes

The increased frequency of climate-driven extreme weather events is already taking a huge toll on the world’s shipping routes, and a potentially historical El Niño event could make things worse.

Panama, for example, has reduced the number of vessels that pass through its critically important canal due to low water levels caused by severe droughts. Such restrictions create a logjam of ships that are waiting to traverse what’s considered a key global trade route.

The Panama Canal Authority, which manages the waterway, said earlier this month that the measures were necessary because of “unprecedented challenges.” It added that the severity of this year’s drought had “no historical precedence.”

The last time a major disruption occurred was in March 2021, when Ever Given, one of the world’s largest container ships, blocked the Suez Canal for nearly a week while contending with strong winds, causing calamity throughout Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

Analysts have since warned that extreme weather driven by the climate crisis could increase the frequency of Ever Given-like events, with potentially far-reaching consequences for supply chains, food security and regional economies.

Panama’s announcement comes a month after the United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization declared the onset of El Niño, which, according to Xeneta’s chief analyst Peter Sands, could exacerbate the disruptions across the world’s shipping routes.

Maritime chokepoints exist “all over the place,” but that typically only calamitous events such as the 2021 Suez Canal obstruction tend to expose the fragility of the “just-in-time” delivery model, Sands told CNBC via a videoconference.

“I think global shipping is like the world’s largest invisible sector,” he added. “We all rely on services and the goods carried by sea, but we hardly ever get to think about how they end up on the shelves — unless something goes wrong.”

But the impact of El Niño, Sands said: “What we see right now is perhaps only the starter of the main course that is being served next year because it could be [a] more severe drought when we get to the first half of 2024.

“Right now, we do not see that filling up of the water levels that a normal year would bring around. So, it is literally a potential disaster in the making,” he added.

While the Panama Canal had seen major delays in the past, the impact of climate change today “is perhaps becoming more prevalent” and “more severe”, according to Lars Ostergaard Nielsen, head of the Americas liner operations center at Maersk, the Danish shipping giant. The drought in Panama, says Nielsen, is prompting Maersk to load approximately 2,000 containers fewer than usual on the same vessel, which makes a “significant difference.”

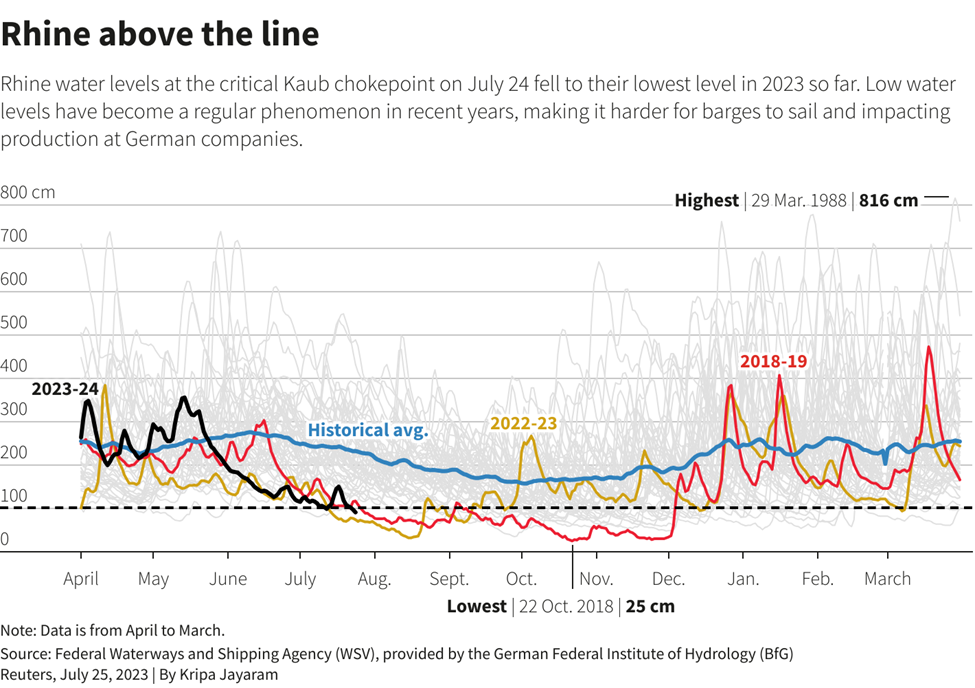

.The Panama Canal isn’t the only major waterway struggling to cope with the effects of extreme weather. Falling water levels on Europe’s busiest waterway have become a regular occurrence in recent years, making it more difficult for vessels to transit at capacity.

The Rhine River, which runs through Germany via European cities to the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, is a prime example. In both 2018 and 2022, the Rhine experienced extended periods of low water levels that restricted shipping volumes. Last year’s 182 million metric tonnes of goods transported via Germany’s waterways represented a 6.4% decline from 2021, and the lowest since German reunification.

“The shipping volumes on the river Rhine have been more or less consistent for the past 20 years or so,” Tim Beckhoff, a procurement and supplier management expert at McKinsey, told CNBC. “And, since 2021, we’ve seen them now dropping year over year. It’s a trend, and probably a trend that’s going to continue.”

In late July, it was reported by Reuters that water levels at Kaub, Germany — a measuring station west of Frankfurt and a key chokepoint for waterborne freight — dropped to their lowest on a year-to-date basis.

As severe heat waves grip southern Europe, the Federal Waterways and Shipping Agency expects the downward trend in the continent’s busiest waterway to continue, and the economic impact would be significant.

According to a study by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IFW), the water at Kaub fell so low for 30 days in 2018 that water transportation on the Rhine reduced by about 25%, and industrial output in Germany fell by 1%.

Of course, in the event of low water levels, rerouting or using alternative transport methods are both possible, but either option would be quite expensive.

For example, a large Rhine barge of about 135m long with a draft of 3m (the maximum depth of the vessel) can carry around 2,700 tons of freight, according to Marc Schattenberg, a Deutsche Bank economist. It would take about 110 large trucks to transport the same load via road, per his calculations.

“These figures illustrate the magnitude that limit rerouting, since alternative means of transport are also running at high capacity,” he told CNBC via email.

Pressure on Commodity Markets

A mixture of continued global warming and the current El Niño cycle would almost certainly set off a ripple effect on the commodities markets, particularly food and agriculture. This can be directly via weather conditions that impact crop yields, or indirectly by disrupting the above-mentioned shipping routes.

We’ve previously highlighted the various reasons why food inflation isn’t going away any time soon. Among those is global warming, which is influencing weather patterns, causing heat waves, heavy rainfall, and droughts, making it difficult to grow crops in many parts of the world year after year.

A study recently published in Nature found that rising temperatures are expected to stall progress on food insecurity by reducing agricultural yields in the coming decades.

Now with El Niño added on top, there would be more droughts in some parts of the world (Brazil, Australia and Indonesia) while more flooding in others (Peru and Ecuador), casting further doubts over the world’s food security.

In an Economist article this week, Maarten van Aalst, director of the Dutch meteorological agency and former head of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, said, “We have never had an El Niño on top of so much global warming, so we don’t know what is going to happen.”

“To put it in real perspective, it’s not just the name El Niño that evokes fear among commodity consumers but the intensity of it. This looks like being a very intense one. Temperatures have been rising for a couple of months,” said Michael Magdovitz, a senior commodity analyst with Rabobank.

In the past, El Niños have in the past driven down rice yields. For example, in 2015-16 South-East Asia’s crop declined by 15 million tonnes, representing 7% of global stocks. Australia, which produces 12-15% of the global crop, sometimes saw its yields halve during El Niño years.

Even before El Niño’s arrival, certain staple crops had already been suffering from climate events. Reuters previously reported that rice futures hit an almost 15-year peak in June as India, Thailand and Vietnam, three of the largest exporters of this staple, experienced record or near-record high temperatures.

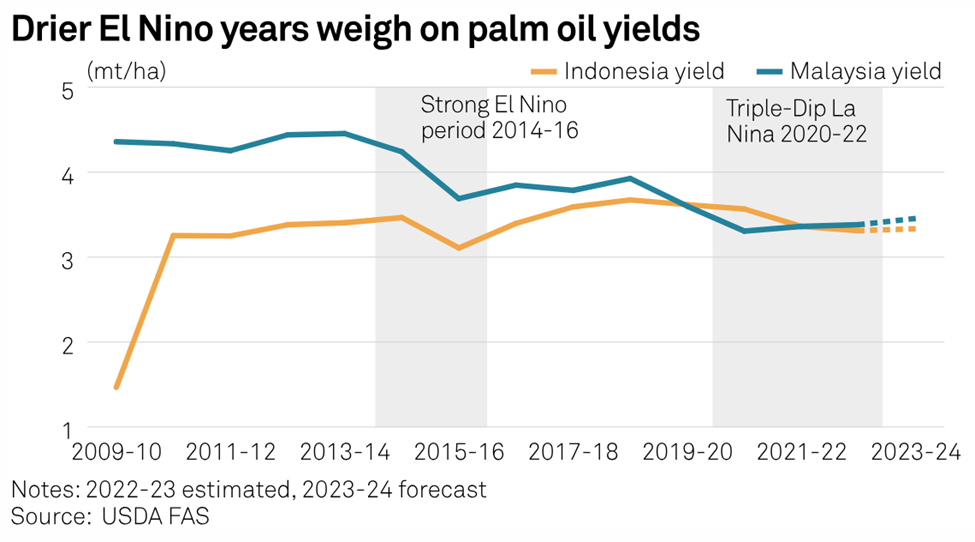

With respect to the impact of El Niño, more drought would impact Australian grains and Indonesian and Malaysian palm oil, and potentially sugar, cocoa and coffee as well, says Rabobank’s Magdovitz.

S&P Global estimates that Malaysian exports of palm oil could fall by 10% if the incipient El Niño is mild and double that if it is severe.

A shortage of palm oils could serve another blow to the already stretched market for edible oils. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, palm oil helped make up for a dearth of sunflower oil, 75% of which is normally produced by the two countries.

In Peru, the water off its coast would get warmer than usual, turning away the species of anchovies that its fishing community relies on, and thus putting a $2 billion a year industry on standstill.

Production of non-food-related commodities could also plummet during an El Niño event. The Economist article noted that in 2015, production at a lithium plant in northern Chile that accounted for 30% of the world’s output was disrupted by heavy rain.

To list out every single possible supply disruption during El Niño years would be impossible, and it’s likely that we won’t know the real impact of the current one for at least a few months, if the current forecast is to be believed.

According to studies, the effects of El Nino tend to peak during December, but the impact typically takes time to spread across the globe. This lagged effect is why forecasters believe 2024 could be the first year that humanity surpasses 1.5 degrees Celsius, according to Professor Adam Scaife, head of long-range prediction at the UK Met Office, who described the El Niño “the biggest single natural variation in climate that we know about on the timescale of a few years.”

Varying Regional Impacts

Of course, no two El Niño cycles are the same, but the weather impacts on different parts of the world tend to follow a similar pattern.

Generally, the Amazon Basin, Australia, the Indian subcontinent, the Sahel, South-East Asia and southern Africa often suffer drier conditions, while Central and East Asia, the Horn of Africa, the southern cone of South America and the southern US usually get wetter.

Also characteristic of El Niño events is the increased likelihood of economic damages, as seen with the supply risks. One study cited by the Economist found that the El Niño cycles of 1982-83 and 1997-98 permanently reduced global GDP by $4.1 trillion and $5.7 trillion respectively.

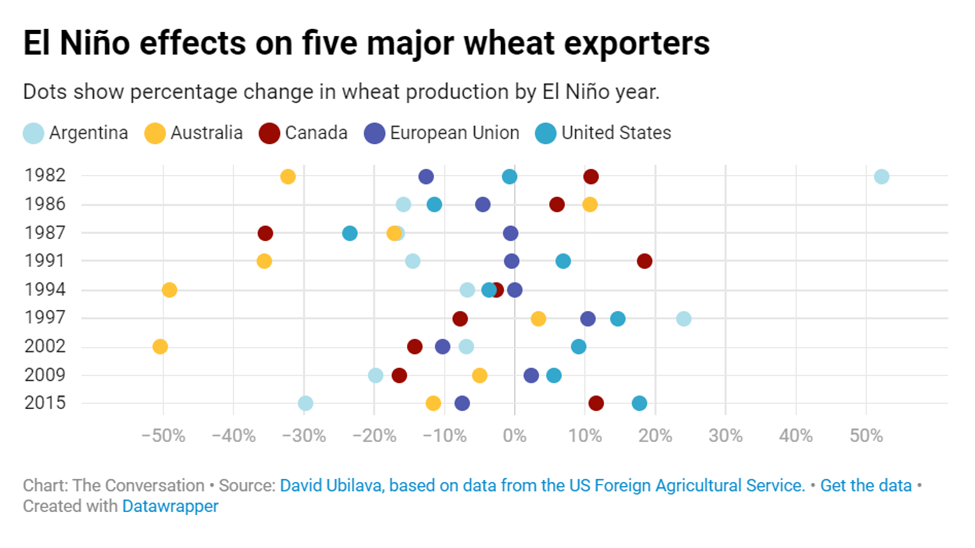

However, some studies, including that by S&P Global, have also pointed to positive net effects from increases in production of some crops in certain regions (i.e. wheat in Argentina).

According to David Ubilava, associate professor of economics at the University of Sydney, the global supply and prices of most food is “unlikely to move that much” during/after an El Niño event.

The evidence from the ten El Niño events in the past five decades suggests relatively modest, and to some extent ambiguous, global price impacts. While reducing crop yield on average, these events have not resulted in a “perfect storm” of the scale to induce global “breadbasket yield shocks”, he wrote.

Like S&P’s analysis, Ubilava uses Australia’s wheat production as an example. In the El Niño years, dips in Australia’s production tend to be offset by changes elsewhere, as illustrated in the graphic below.

Despite the differing views on El Niño’s economic impacts, most agree it is the developing countries that are usually hit harder by El Niño, which would make sense as the fate of these economics is tied closely to climate and agriculture.

Conclusion

With the official arrival of El Niño, the next great threat to the global economy is here.

Previous episodes of El Niño have all led to drastic weather changes that ravaged some of the most productive regions of the world, leading to spikes in commodities. An International Monetary Fund paper found that non-fuel commodities have risen 5.3% in the first four quarters after the start of past El Niño cycles, with crude oil rising 13.9%.

But this time, with global warming, the knock-off effects could be even bigger than ever before.

Compounding the issue is the fact that some of the most valuable commodities — namely key minerals used in clean energy technologies — are concentrated in certain regions that are prone to extreme weather. In turn, this would delay global efforts to tackle global warming, meaning the effect of El Niño could be longer lasting than just a few years.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.