How climate change is reducing food production and pushing tens of millions to the brink of famine

2021.07.27

A scorching summer heat wave, thought to that killed over 700 Vancouver-area residents unprepared for temperatures above 40 degrees Celsius, is part of a disturbing trend of extreme weather caused by global warming.

This “new normal” of suffocating heat, droughts, freak storms and flooding, is not only causing discomfort and in cases of the most vulnerable, deaths, it is reducing the amount of available food that could lead to the starvation of millions worldwide.

The United Nations Food Program is warning of a “looming catastrophe”, with about 34 million globally on the brink of famine. The group points to climate change as a major contributor to the sharp increase in hunger, and emphasizes that food inflation is on the rise as farmers deal with the impacts of extreme weather.

Meanwhile a study by Cornell University found that rising global temperatures have prevented a fifth of agricultural output since the 1960s — the equivalent of losing the last seven years of productive growth.

According to the study mentioned in a recent Bloomberg article, The loss of productivity comes even as billions has been poured into improving agricultural production through the development of new seeds, sophisticated farm machinery and other technological advances.

“Even though globally agriculture is more productive, that greater productivity on average doesn’t translate into more climate resilience,” said Ariel Ortiz-Bobea, an author of the paper and associate professor at Cornell’s Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management.

Extreme weather

A prolonged period of hot weather in southern British Columbia has set tinder-dry forests ablaze. At time of writing there were 254 active forest fires, according to the BC Wildfire Service, and 1,223 year to date, an increase of 17 this week and 14 in the past two days. Out-of-control wildfires, evacuation orders, and dangerous to breathe smoke that blankets communities for weeks, are now an annual event in much of the BC Interior.

The “heat dome” that covered much of western North America at the end of June, shattering temperature records, isn’t the only weather event making headlines. There have also been unprecedented rains followed by catastrophic flooding in China and Europe, and temperatures reaching 49 Celsius in normally temperate Finland and Ireland.

In Barrie, Ontario, a tornado designated as EF-2 (wind speeds up to 217 km/h) slammed into a residential neighborhood destroying homes and injuring 11 people. The twister was one of five recorded in southern Ontario.

We don’t have to wait years for the worst impacts of climate change to occur. They’re already here.

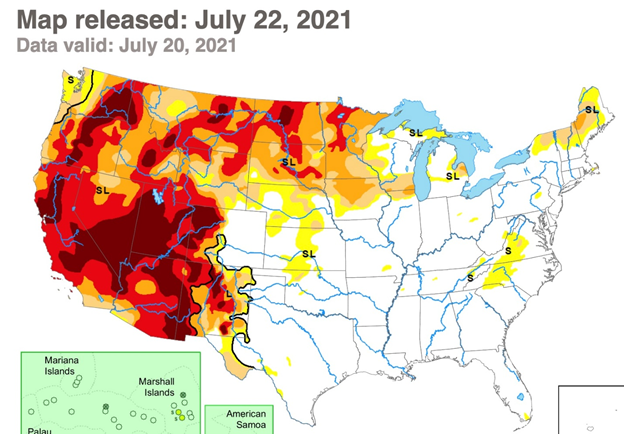

The monstrous wildfires happening in the United States are the latest consequence of a 21-year drought in the southwestern US (and into the northern states including Oregon), as depicted in the latest map by US Drought Monitor. Red areas are extreme drought, brown areas show exceptional drought. The current dry stretch started in 2000 and hasn’t let up, putting it second only to a highly arid period in the last 1500s.

The Earth’s orbital processes are thought to be the most significant drivers of ice ages and, when combined, are known as Milankovitch Cycles. The last ice age occurred between 27,000 and 24,000 years ago. But we know from geological records — studies of Danish and Swedish bogs and lakes, for example — that as the Earth has warmed and cooled over the centuries, the warmer periods are getting longer and the colder periods shorter. In order words, spread out over an extremely long-time sequence, the Earth is gradually getting hotter even as it warms and cools in cycles.

Climate is also affected by changes occurring within the sun, thus shifting the intensity of sunlight that reaches the Earth’s surface. These changes in intensity can cause either warming — stronger solar intensity — or cooling when solar intensity is weaker.

Despite the promises of politicians and certain business leaders who claim to have the answers to stop global warming, the truth is it is unstoppable. The inescapable conclusion? The world will keep warming until it starts cooling. We are all on an upward global warming escalator that has no down option. The only question is, how fast will the escalator move?

In 2018 the world’s leading climate scientists warned there are only 12 years to go for warming to be kept to a maximum 1.5 degrees C. If, after a dozen years, not enough is done to slow global warming, a tipping point will be reached, beyond which the risk of droughts, floods and extreme heat, will significantly worsen.

How are we doing with that? Not so great. One only has to look at regional climate/ weather maps to see that major changes are taking place before our very eyes.

It’s not that the Earth is warming faster — temperatures are in line with climate science’s expectation of 1.2 degrees higher than pre-industrial levels. Rather, the impacts are greater than scientists predicted.

“As I speak, it is clear that extreme weather is the new normal. From Germany to China to Canada or the United States: wildfires, floods, extreme heat waves. It is an ever growing tragic list,” Reuters quotes Joyce Msuya, deputy executive director of the U.N. Environment Program, during the event’s opening ceremony on Monday.

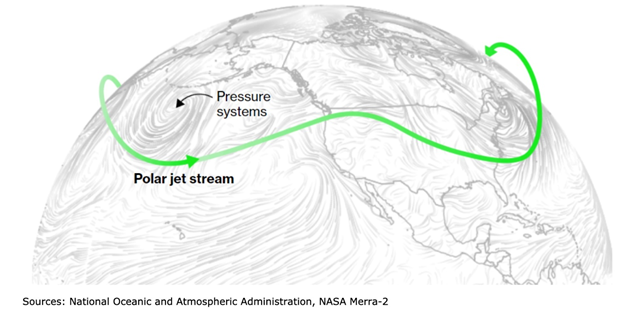

As for what is causing the extreme heat, fires and flooding, studies suggest that climate change is slowing down parts of the northern polar jet stream. As the jet stream weakens, it traps heat under high-pressure air in a “heat dome”. Storms become “stuck” over an area for longer than usual, resulting in heavy rains and flooding.

Meteorologists worry whenever those swings and dips form omega-shaped curves that look like waves. When that happens, warm air travels further north and cold air penetrates further south. The result is a succession of unusually hot and cold weather systems along the same latitude. Under these conditions, winds often weaken and dangerous weather can remain stuck in the same place for days or weeks at a time—rather than just a few hours or a day—leading to prolonged rains and heat waves.

Green Revolution failure

Common sense holds that technology will be able to beat back the worst effects of climate change, as agronomics comes up with new ways to increase yields in drought-prone areas.

Unfortunately this is not proving to be the case. The Phys.org article states that “The loss of productivity comes even as billions has been poured into improving agricultural production through the development of new seeds, sophisticated farm machinery and other technological advances.

Even though globally agriculture is more productive, that greater productivity on average doesn’t translate into more climate resilience,” said Ariel Ortiz-Bobea, an author of the paper and associate professor at Cornell’s Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management.

The damages to productivity growth aren’t evenly spread across regions. Warmer areas — especially those in the tropics — are more detrimentally affected. Ortiz-Bobea said that coincides with many countries where agriculture makes up a bigger share of the economy.

He has also warned that current research into improving production may not enough consider the pace of climate change.

“I worry that we’re breeding or preparing ourselves for the climate we’re in now, not what is coming up in the next couple of decades.”

The modern agricultural complex spawned by the Green Revolution may have allowed us to grow more food, but dependence on this high-cost industrial system has come at a high price, mostly for farmers.

Output did increase, but the energy input to produce a crop increased faster. This is because high-yielding seed varieties only outperform traditional varieties when adequate irrigation, pesticides and fertilizers are used.

The Union of Concerned Scientists notes that monoculture – repeatedly producing the same crop at the exclusion of others — is bad for the soil, preventing the formation of deep root systems and the buildup of organic matter, and hastening the time when the soil can no longer holds its nutrients and irrigation ends up stripping nitrates out of the soil and polluting nearby fresh water supplies.

The UN says that by 2030 an area twice the size of South Africa will become unproductive due to desertification, land degradation and drought.

Desertification is a phenomenon that ranks among the greatest environmental challenges of our time.

It’s a process whereby land in arid or semi-dry areas becomes degraded — the soil loses its productivity and the cover vegetation disappears or is degraded to the point where wind and water erosion carry away the topsoil, leaving behind a highly infertile mix of dust and sand.

Desertification is a global issue with more than half of Earth’s arable land affected by soil degradation, according to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification.

Currently 12 million hectares of arable land is lost to drought and desertification annually. The issue is said to affect 1.5 billion people in over 100 countries.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates if the phenomenon isn’t stopped, by 2030 Africa will lose two-thirds of its farmland.

The issue of desertification is not new, it has constantly played a significant role in human history, even contributing to the collapse of the world’s earliest known empire, the Akkadians of Mesopotamia.

Desertification is made much worse by climate change.

Ranching and farming, through extensive energy inputs like diesel fuel, lights, heating, etc., generate high amounts of carbon dioxide. Farming also releases methane from cows and cow manure, and nitrous oxide from fertilizers. Both are heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

As farmlands expand to meet demand for more food, forests are destroyed to make room for crops. Trees are carbon sinks that trap CO2 and prevent warming. Their removal dampens the forests’ mitigating effects on emissions from farming, therefore temperatures continue to rise, in a feedback loop.

A good example is soybeans. 95% of the soy that is made from soybeans, is used as animal feed. To feed 700 million pigs in China — one for every two citizens — requires the importation of 800 million tonnes of soy. A lot of soybeans come from the Amazon region of Brazil, where rainforests, considered one of the most effective carbon sinks on the planet, must be logged to make room for more soybean farms.

It’s not only the constant clearing of forest for farmland that is a fall-out from climate change. Rising temperatures have also been shown to decrease crop yields.

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would on average reduce global yields of wheat by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

A new study showed more than a fifth of global food output growth has been lost to climate change since the 1960s, putting an estimated 34 million people on the brink of famine.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment found that climate change is already shrinking food supplies, particularly rice and wheat. More importantly in terms of ameliorating global famine, an estimated 795 million people still regularly don’t have enough to eat.

Disturbingly, the study quoted by The Conversation found that rising temperatures have reduced consumable food calories by 1% a year for the top 10 crops – maize (corn), rice, wheat, soybeans, oil palm, sugarcane, barley, rapeseed (canola), cassava and sorghum.

The industrial model dominating American agriculture makes it especially vulnerable to climate changes. Consider cattle ranching, which accounts for a whopping 50% of US agricultural revenue.

Raising cattle for beef consumption reportedly requires 28 times more land, 6X more fertilizer and 11X more water compared to pork, chicken, dairy and eggs.

Not only does industrial-scale beef production use a heck of a lot of resources, it’s also harmful to the environment, emitting about 200 kilograms of CO2 per kg, five times other food sources, and sucking up about 15,000 liters of water per kilo.

Extreme heat and more temperature fluctuations are hard on plants. Heavy rains cause flooding, which can devastate crops and livestock, accelerate soil erosion and pollute water.

Droughts are exacerbated by rising temperatures, reduce crop yields and cause irrigation water shortages. Crops near coastal areas can also be ruined by saltwater intrusion as a result of storm surges or rising seas.

There are several examples of recent extreme weather events having a negative impact on food production.

Ruined crops

Perhaps the most dramatic is Brazil, where a once in 20 years frost killed most of the young coffee trees in the world’s largest grower of the caffeinated beverage. Prices rose 17% this week and topped $2 a pound for the first time since 2014.

Talk about extremes. The country is also experiencing a drought that has depleted reservoirs needed for irrigation.

Globalization long ago did away with regional food markets; the ability to refrigerate and ship food thousands of kilometers away means that what happens in one country affects the world. This is particularly the case in Brazil, which ships the most sugar and orange juice and is among the top producers of corn and soybeans. The sprawling South American nation also accounts for around 40% of the world’s arabica harvest, the high-quality coffee beans known for their smooth flavor.

“There’s no other country in the world that has that kind of influence on the world market conditions — what happens in Brazil affects everyone,” Bloomberg quotes a buyer from Intelligentsia Coffee, a Chicago-based roaster and retailer.

The Bloomberg story notes, What’s unique right now is that extreme weather seems to be pounding almost every region of the globe.

Food inflation

It couldn’t have come at a worse time.

The coronavirus pandemic has put tremendous pressure on supply chains, and the prices of many agricultural commodities such as grain, corn and soybeans, have skyrocketed. This is due to a number of reasons including heavy demand from China, whose economy grew at a blistering 18% in the first quarter, bad weather and droughts.

A shortage of supply, and a need to replenish hog herds after an outbreak of deadly African swine fever, is expected to push corn imports to 28 million tons this season, the most on record, according to Bloomberg data.

The news sent corn prices to over $6 a bushel in May, an 8-year high. Corn prices have nearly doubled (+84%), soybeans have gained 72%, sugar is up 59% and wheat has climbed 19%.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), global food prices have risen for nine straight months, and are close to their 2011 peak.

Increases in the prices of grains, like corn and soybeans used in animal feed, typically get passed down the supply chain to the cost of meats, including chicken, pork and beef.

But it’s more than just adding a few dollars onto your weekly shop.

As the Bloomberg story notes, Climate change and associated weather volatility will make it increasingly harder to produce enough food for the world, with the poorest nations typically feeling the hardest blow. In some cases, social and political unrest follows.

The most obvious example is the Arab Spring, when riots broke out in Egypt (and Tunisia) over a 37% increase in bread prices. Moreover, there is a disturbing indication that the series of anti-government protests, uprisings and armed rebellions which spread across much of the Arab world in 2010, could happen again. According to Bloomberg’s Emerging Market Food Vulnerability Scorecard, Yemen, Sudan and Lebanon are the countries most at risk.

And lest it be dismissed as “a Third World problem”, readers should understand that food inflation and food insecurity is happening right here in Canada and the United States.

In western Canada, rail cars carrying grain for export have been idled for weeks due to dangerous wildfires spanning five provinces and two territories.

Drought conditions in the Prairies have withered crops and in the northern US, forced farmers to sell their low-yielding wheat and barley as livestock feed. The region’s spring wheat prices recently hit their highest level in more than eight years.

The smell of rotting shellfish is another manifestation of freakishly hot weather in the normally mild Pacific Northwest. As temperatures soared past 40 degrees C, fresh clams, mussels, and oysters succumbed. According to one UBC researcher, a billion sea creatures on the coast of Vancouver perished from the unbearable heat.

Canada’s Food Price Report predicts that prices will increase as much as 5% this year, representing almost $700 more for groceries, for the average Canadian family.

In the United States, food prices climbed 2.4% in June compared to the same month a year ago, including a 4.2% rise in restaurant and take-out meals.

According to the USDA, beef and veal prices are predicted to increase between 3 and 4% this year, pork prices are expected to rise 4-5%, poultry prices between 2.5 and 3.5%, and prices for the aggregate category of “meats” are predicted to increase between 3 and 4%. Fresh fruit prices are expected to go up between 5 and 6% in 2021, with prices for the aggregate category of “fresh fruits and vegetables” predicted to increase between 2.5 and 3.5%, states the USDA.

Rising hunger

Global food price increases are clearly of concern for seniors living on fixed incomes, the poor on social assistance, and the working poor getting by paycheck to paycheck.

In India, the coronavirus and a stalled monsoon have conspired to lift food prices by 5%. That is a huge deal for the millions who have lost their jobs and whose families are now on the brink of starvation.

According to a recent article, more than 15 million Indians were unemployed in May, when covid-19 infections peaked. The story cites a survey by the Azim Premji University in Bangalore, stating that 90% of respondents reported their household had suffered a reduction in food intake as a result of the lockdown.

Between the start of the outbreak in March 2020, and the end of October, the study found the number of people living in households with daily incomes below $5, spiked from 298.6 million to 529 million.

Bloomberg states, All of [the unemployment ] is leading to an increase in hunger, particularly in urban areas, in a nation that already accounts for nearly a third of the world’s malnourished people. While few statistics are available, migrants and workers at food distribution centers in major Indian cities say they can’t remember seeing lines this long of people yearning for something to eat.

Conclusion

The Earth will keep warming, until it starts cooling. We are all on an upward global warming escalator that has no down option. The only question is, how fast will the escalator move?

Recent extreme weather events indicate that climate change is not only happening before our very eyes, it is accelerating. More accurately, the impacts of global warming are greater than scientists have predicted.

One of the most important consequences of rising temperatures is their impact on food production.

The United Nations Food Program is warning of a “looming catastrophe”, with about 34 million globally on the brink of famine. The group points to climate change as a major contributor to the sharp increase in hunger, and emphasizes that food inflation is on the rise as farmers deal with the impacts of extreme weather.

Meanwhile a study by Cornell University found that rising global temperatures have prevented a fifth of agricultural output since the 1960s — the equivalent of losing the last seven years of productive growth.

Without life-giving bands of precipitation to wet parched soil, farmer worldwide are expected to go through another rough growing season.

Lower crop yields mean higher prices for agricultural commodities. Food producers see their margins squeezed by higher input costs and pass these onto consumers.

A higher-income household can shrug off a 5, 10, even a 20% increase in grocery prices. Not so for families and individuals whose grocery budgets are tight.

As incomes rise, households spend more on food but it represents a smaller share of their overall budget. Lower-income people don’t have room in their budgets for much other than food and shelter.

According to the USDA, in 2019 the poorest households spent an average 36% of their disposable income on food, compared to the 10% that most Americans spend.

With the difficulties covid-19 has placed on grocery supply chains, 2020’s figure is expected to be higher. Some are predicting the percentage of disposable personal income the average US household spends on food will reach 40%, with poorer families having to spend well over 50%.

US food price increases are already at their highest in nine years, and the consumer price index rose the most in April of any 12-month period since 2008. The CPI in June hit 5.4%, well beyond the central bank’s 2% target.

Among the crops already seeing drought conditions are corn, soybeans, wheat, sorghum and cotton. Hay crops and cattle production are also expected to be hit hard.

A lack of snow-melt runoff and precipitation, in an El Nina year made worse by climate change, has left reservoirs at a fraction of their normal levels, endangering millions of people that depend on them including farmers and ranchers that need to irrigate crops/ water herds.

California has declared a drought emergency in 50 of 58 counties, and an official water shortage declaration for the Colorado River basin, where a prolonged 21-year warming and drying trend is pushing the nation’s two largest reservoirs to record lows, is expected soon.

The price of food is skyrocketing and it’s going to push millions, including in normally sheltered North America, to cut back on the basic essentials of life including meat, fruit and vegetables.

When people are starving, when they have no water to drink, when their kids are screaming and crying, when the heat is brutal and unbearable, they really have nothing to lose. It all points to a grim, potentially explosive situation.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.