‘Greenwashing’ is tainting the rush to electrification

2021.06.11

What’s the point of making supposedly “green” battery components when the refining process is so dirty?

The mining industry may have achieved progress in recent years regarding environmental, social and governance (ESG), the new corporate buzz word, but in parts of the (mostly) developing world, the industry is still sporting a black eye.

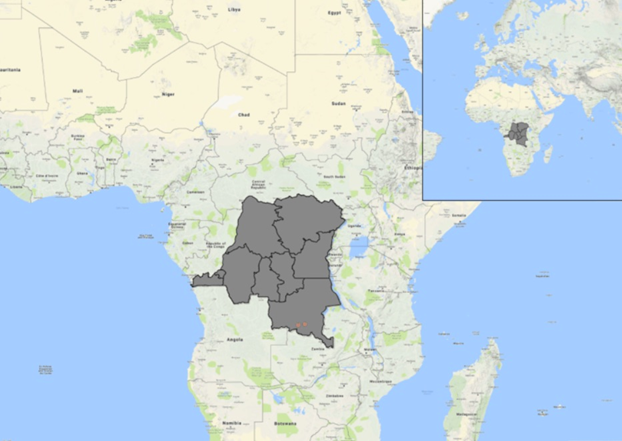

Mining practices in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have elevated the issue of “conflict minerals” to the public consciousness, with stories of armed groups operating cobalt mines dependent on child labor, as well as in Guinea, where riots have broken out over bauxite mining.

Rare earths mining and processing in China, the extraction and refining of laterite nickel in Indonesia, and cobalt mining in the Congo, are three good examples of the disconnect between the rhetoric being delivered lately regarding the so-called new green economy, and reality.

In many respects the widely touted transition from fossil fuels to renewable energies, and the global electrification of the transportation system, are not clean, green, renewable or sustainable.

The dark side of green

In China’s Inner Mongolian city of Baotou, dozens of pipes churn out a torrent of thick black chemical waste that flows into an artificial lake filled with toxic sludge. A constant smell of sulfur pervades the apocalyptic scene. Most people in the West haven’t heard of Baotou but its mines and factories are one of the biggest suppliers of rare earth minerals used in a plethora of so-called green applications, everything from wind turbines to electric vehicles to nuclear reactors.

The ecological risks (air pollution, biodiversity loss (wildlife, agro-diversity), desertification/drought, food insecurity (crop damage), loss of landscape/aesthetic degradation, soil contamination, soil erosion, waste overflow, deforestation and loss of vegetation cover, surface water pollution/decreasing water quality, groundwater pollution or depletion, mine tailings spills (large-scale disturbance of hydrological and geological systems) of rare earths mining aren’t confined to China, which mines and processes most of the materials.

In 2019 Malaysian environmental groups demonstrated over concerns about radioactive waste from Australian rare earths miner Lynas Corp’s processing plant located there.

In Indonesia, nickel is produced from laterite ores using the environmentally damaging HPAL technique. The advantage of HPAL is its ability to process low-grade nickel laterite ores, to recover nickel and cobalt. However, HPAL employs sulfuric acid, and it comes with the cost, environmental impact and hassle of disposing the magnesium sulfate effluent waste.

The Indonesian government only recently banned the practice of dumping tailings into the ocean for new smelting operations, but it isn’t yet a permanent ban.

Most of four HPAL plants currently under construction, led by Chinese stainless steel producers and battery makers, plan to continue the environmentally egregious practice of DST, due to the much higher cost of managing the tailings on land.

Not only that, the process of refining nickel to make nickel pig iron, and now, nickel matte, is highly energy-intensive (it relies on coal-fired power) and creates a lot of air pollution.

Producing 1 ton of nickel in nickel pig iron creates 45 tons of carbon dioxide emissions, compared to just 20 tons for coal-powered aluminum and steel production requiring an average 2 tons of CO2 per ton of metal.

Chinese nickel pig iron producers in Indonesia now are looking to make nickel matte, from which to turn laterite nickel into battery-grade nickel for EVs. The process however is highly energy-intensive and polluting, as well as far more costly than a nickel sulfide operation (up to $5,000 per tonne more).

According to consultancy Wood Mackenzie, the extra pyrometallurgical step required to make battery-grade nickel from matte will add to the energy intensity of nickel pig iron (NPI) production, which is already the highest in the nickel industry. We are talking 40 to 90 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per tonne of nickel for NPI, versus under 40 CO2e/t for HPAL and less than 10 CO2e/t for traditional nickel sulfide processing.

Indonesia is the world’s top producer of nickel and tin. Aside from environmentally damaging nickel mining/ processing, it has recently come to light that tin mining in the archipelago nation has migrated to the ocean, where it is stirring up all kinds of trouble.

As reserves of tin, heavy used in electronics as a component of solder, including upcoming green applications, become depleted in the mining hub of Bangka-Belitung, Indonesia, mining companies are turning to the sea.

Artisanal miners extract the lustrous metal by operating pontoons with long pipes that suck up sand from the seabed. The slurry is then run across a bed of plastic mats that trap the black sand containing tin ore.

State miner PT Tinah’s proven tin reserves on land were 16,399 tonnes last year, compared with 265,913 tonnes offshore.

According to Reuters, The huge [offshore] expansion, coupled with reports of illegal miners targeting offshore deposits, has heightened tension with fishermen, who say their catches have collapsed due to steady encroachment on their fishing grounds since 2014…

[Fisherman Apriadi Anwar] says fishing nets can get tangled up in offshore mining equipment, while trawling the seabed to find seams of ore has polluted once-pristine waters.

“Fish are becoming scarce because the coral where they spawn is now covered with mud from the mining,” he added.

Greenwashing

As defined by Investopedia, “Greenwashing is the process of conveying a false impression or providing misleading information about how a company’s products are more environmentally sound. Greenwashing is considered an unsubstantiated claim to deceive consumers into believing that a company’s products are environmentally friendly.”

Greenwashing claims are often directed at companies making consumer products when it’s found that the amount of carbon-based fuels that go into the product, cancel out its eco-friendly credentials.

Greenwashing can also be applied to mining, wherein the amount of energy and pollution that goes into a mineral’s extraction, nullifies the “green-ness” of its end products.

When it comes to electric vehicle production, the mining of EV battery metals such as lithium, nickel, cobalt and manganese, plus copper used in the electric motor and wiring (along with copper used in EV charging stations) would have to result in a lower carbon footprint than the amount of carbon saved by not making vehicleswith an internal combustion engine, for the process to be called green.

Same with renewable energy. If mining silver, for example, used in solar panels, is so carbon-intensive that it cancels out the positive environmental impacts of solar-powered energy, there is a good argument for discontinuing silver mining for solar panels, and finding a substitute.

I recently read an article containing a quote from Robert Friedland, the mining magnate behind Ivanhoe Mines, who states: “The average person just doesn’t understand the scale of the implication for raw materials,” he said. “If you’re not just greenwashing, and you really mean it, then it is the revenge of the miners.”

I happen to agree with him. Most people are ignorant of how minerals like copper, without which the green revolution doesn’t happen, could determine whether or not society is able to make the transition from fossil fuels to electrification and decarbonization.

Where I disagree with Friedland is his solution: mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where Ivanhoe’s massive Kamoa-Kakula copper project has just reached commercial production.

The rape capital of the world

In the June 9 Bloomberg article, the always-colorful Friedland argues the African nation “emerging from decades of conflict and corruption holds the key to greening the global economy.”

The reason, Friedland says, is due to copper deposits in Chile, the world’s top red-metal producer, deteriorating in ore quality, along with evidence of increased resource nationalism including attempts by the state to restrict water rights, and a new royalty tax regime that could see miners taxed up to 75% of their profits if the copper price is above $4 a pound.

“If we came from Mars and we were sent in our flying saucer to orbit the Earth to find copper, we would definitely go to Katanga in the southern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo as the richest place on the planet for copper,” Friedland was quoted saying.

The country may have an abundance of high-quality copper ore, but it is also an economic and political basket-case.

The DRC holds two major distinctions. First, it is the richest country in the world in terms of mineral wealth, at an estimated $24 trillion. Second, it is the country in which the highest number of people — estimates go as high as 10 million — have died due to war since World War II.

The Congo’s staggering economic potential (the DRC contains 5% of the world’s copper and 50% of its cobalt) is matched only by its poverty and corrupt mismanagement.

The Democratic Republic of Congo ranks last on the UN Human Development Index (HDI) rankings which represent an annual assessment of measures of progress in human well-being. Countries at the bottom of the list suffer from inadequate incomes, limited schooling opportunities and low life expectancy rates due to preventable diseases such as malaria and AIDS.

UN special representative Margot Wallstrom called the DRC “the rape capital of the world” and both government forces and the militias in control of various parts of the country practise it.

“In 1994 the world watched Africa in horror as some 800,000 people were killed without regard for sex or age over the course of some hundred days; it was the Rwandan Genocide and commanded global guilt if not global action. In March, 1998, President Bill Clinton stood on the tarmac of Rwanda’s Kigali airport and expressed to on looking crowds his failure to stop the genocide was the “biggest regret” of his presidency. Only six months later residual Hutu-Tutsi hostilities ignited the Second Congo War which lasted five years, directly involved eight African nations and twenty-five armed groups, claimed 5.4 million lives, and garnered little global attention. While the deadliest conflict since WW2 may have been initiated by deep ethnic and political tensions, the violence and bloody aftermath which perpetuates today was driven in large part by something deeper still: Congo’s mineral wealth.

Many of Africa’s resource-rich countries emerge from years of civil war with residual conflict zones, but in this case Congo is in a tragic class of its own. The enduring legacy of the Second Congo War is the continuing conflict in Congo’s eastern provinces…Known as the Kivu Conflict, in 2004 this armed struggle between government forces and rebel militias picked up the Second Congo War’s bloody baton and continues today due to innumerable artisanal mines funding a perpetual conflict whose brutality includes mass rape, mutilation, and cannibalism. The UN believes over 50% of the region’s 200 mines are controlled by armed forces which employ illegal taxation, extortion, forced labor, and violence to ensure the flow of mineral wealth. According to one CNN report eastern Congo’s armed groups generate some $180 million through the illicit trade of tin, coltan, tungsten, and gold which are easily traded across the porous eastern frontier and funneled into the international market…This volatile mixture of extraordinary mineral wealth, ethnic tension, and proxy armies can drag the region into another brutal war…With tensions high and 1994’s genocide still casting its shadow over the region another devastating war remains a looming and distinct possibility.” — Nathan William Meyer, ‘Deal of the Century: Will Chinese Investment Save Congo’

In terms of mining investment attractiveness, the DRC ranks far down the list of countries considered the best places for mining companies to do business, according to the latest (2020) Fraser Institute rankings.

Another recent study pointed to 34 countries that have seen a significant increase in resource nationalism risk over the past year. Countries now rated “extreme risk”, according to the March 2021 report by Verisk Maplecroft, include major African copper producers Zambia and the DRC.

The Congolese government in 2018 raised taxes on mining firms and increased royalties, and just last month, slapped a ban on the export of copper and cobalt concentrates — an action almost identical to what has happened in Indonesia with nickel.

Questionable plan for power

Back to Robert Friedland, the billionaire Ivanhoe Mines Executive Co-Chairman, says the tide is turning against large South American copper porphyry deposits like Escondida, as declining ore grades and the need to decarbonize operations are exposing how much power and water these mines use, again we agree.

In contrast, Friedland says that richer deposits in the Congo can run at a smaller scale using hydro power, limiting their carbon footprint, presumably including Ivanhoe’s new Kamoa-Kakula DRC mine, which Friedland wants to turn into one of the world’s largest and greenest.

That might be possible if the DRC had plentiful low-carbon power, but it doesn’t; while some large miners are building or renovating hydroelectric power plants, diesel generators at many minesites are still the norm.

What little power the country does have, goes to its mines; only about 13.5% of the population has access to electricity, with blackouts common — hardly a situation conducive to re-building civil society in a country racked by war, disease and widespread poverty.

“It’s not that the DRC has really reduced its country risk dramatically,” Bloomberg quotes Erik Heimlich, a Santiago-based copper analyst with research firm CRU. “Everywhere is becoming more complicated to develop projects so by comparison they look better,” he explained, referring to Chile and Peru, the world’s top two copper producers, where politicians are aiming to take a bigger share of miners’ profits.

Indeed what Friedland is planning to do in the DRC, ie., dam rivers and build dams to glean cheap hydro power, is anything but green. In northeastern British Columbia, where the new Site C dam is being built, damming a new section of the Peace River will flood 80 km of river valley. A joint federal-province environmental impact assessment concluded that the dam would “severely undermine” use of the land, and make fishing unsafe for at least a generation.

Moreover, despite Ivanhoe vowing to produce the industry’s “greenest” copper, there is no indication that will happen anytime soon. It will take years to build hydroelectric power to replace diesel-fueled power generation at DRC mines.

In the meantime, Ivanhoe will export copper mined from Kamoa-Kakula, to China for processing.

This week the company signed an offtake agreement with Citic Metal, and a subsidiary of China’s Zijin Mining, to sell each 50% of the copper products from Kamoa-Kakula’s Phase 1 production. A local DRC copper smelter 100% owned by Chinese companies will produce blister copper.

Nothing green here

Shipping copper concentrate to China for refining, via ocean carriers run on dirty bunker fuel, and where many of the smelters are powered by coal, is arguably a step backward for the green revolution. In fact the country’s copper smelters are trying to reduce purchases of concentrate this year in an effort to curb China’s carbon emissions.

Unfortunately, it appears that most of the companies found by Ahead of the Herd while researching this article, are no better than Ivanhoe in terms of greening their supply chains.

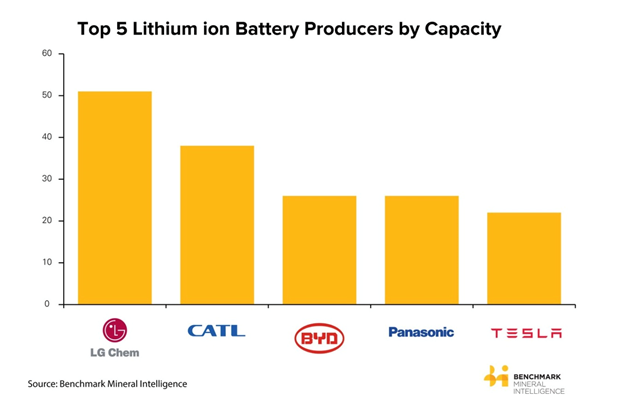

With the exception of Tesla, the supply chain for electric vehicles is dominated by Asian firms.

CATL

Among the world’s leading EV battery-makers are China’s Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL), Japan’s Panasonic, China’s BYD backed by US investor Warren Buffett, Korea’s LG Chem, Samsung SDI and SK Innovation.

CATL batteries are installed in electric cars manufactured by BMW, Volkswagen, Daimler, Volvo, Toyota and Honda.

China’s largest lithium battery maker bought an 8.5% stake in Australian miner Pilbara Minerals, which exports a concentrate from the lithium mineral spodumene.

CATL also reportedly plans to invest $5 billion in a lithium battery plant in Indonesia, having signed an agreement with state miner Aneka Tambang requiring CATL to ensure that 60% of nickel is processed into batteries in Indonesia.

You can bet that this nickel ore, mined from nickel laterites, will be processed using the dirty HPAL method, with the tailings likely dumped into the sea.

Panasonic

Panasonic is the third largest supplier of EV batteries. In 2014 the Japanese conglomerate partnered with Tesla to build Giga Nevada, the world’s biggest lithium-ion battery factory, and it recently joined forces with Toyota to construct a battery plant in Japan starting in 2022. Panasonic sources its nickel from Sumitomo Metal Mining Corp, which gets most of the battery ingredient from the Philippines (again, from nickel laterites, employing the expensive and polluting HPAL processing method).

LG Chem

LG Chem won a contract to supply the GM Volt in 2008. The Korean company also counts Ford, Renault, Hyundai, Tesla, Volkswagen and Volvo among its customers.

In 2020 LG Chem separated its battery-making business into a new company, LG Energy Solution, inked an eight-year deal with Chilean state-owned lithium miner SQM, and signed a nickel and cobalt offtake agreement with Australia’s Queensland Pacific Metals Ltd (formerly Pure Minerals), which owns the Townsville Energy Chemicals Hub (TECH) in the city of the same name. TECH will process ore imported from New Caledonia to produce nickel sulfate, cobalt sulfate, alumina and other by-products.

Also last year, Reuters reported LG Chem was considering a $9.8 billion investment in an electric vehicle factory in Indonesia, integrated with a smelter. Few details on the plant were published but we can assume the nickel being processed will come from laterites. The same for TECH’s project in Queensland, sourcing nickel from New Caledonia. Ore from the region is typically laterite, therefore the processing method is likely HPAL, although Queensland Pacific Metals says on its website it will “leave almost zero waste products.”

This week LG Energy purchased a US$10.8 million stake in Queensland Pacific Metals and made a separate agreement with the company to buy 7,000 tonnes of nickel and 700 tonnes of cobalt a year from the TECH smelter from 2023.

Samsung SDI

The affiliate of tech giant Samsung has EV battery plants in South Korea, China and Hungary, supplying automakers such as BMW, Ford, Volvo and Volkswagen.

Queensland Pacific Metals in 2020 signed a non-binding offtake agreement with Samsung SDI to supply 6,000 tonnes of nickel per year from its TECH smelter.

Tesla

With 28% of global market share, as of the first half of 2020, Tesla is the undisputed EV manufacturing leader.

Elon Musk’s company has publicly stated its biggest challenge in terms of scaling its lithium-ion cell production, is nickel supply.

In March, Tesla announced it is partnering with the Goro nickel mine in New Caledonia, owned by Brazil’s Vale. As mentioned, nickel laterites from New Caledonia are typically processed using the highly polluting HPAL method.

Musk has repeatedly stated that Tesla would source its EV raw materials from mines in North America, however the mercurial chief executive has done the exact opposite.

Tesla currently sources three-quarters of its lithium feedstock from Australia and over a third of its nickel. On June 2 Robyn Denholm, chair of the US carmaker, said Tesla plans to buy more than $1 billion of Australian battery metals a year, including spodumene from the continent’s hard rock lithium mines.

It’s also been reported that China’s Ganfeng Lithium is Tesla’s largest supplier of lithium hydroxide for EV batteries, and that at the end of December, 2020, the automaker signed a five-year deal with China’s Yahua Industrial Group, to supply lithium hydroxide.

Ganfeng Lithium is China’s largest lithium producer which, along with US-based Albermarle and Chile’s SQM, controls over 70% of global lithium supply. The Mount Marion mine in Western Australia is Ganfeng’s largest source of lithium. The company also mines brine lithium in Argentina and is reportedly experimenting with clay extraction methods in Mexico, signing a joint-venture agreement with Bacanora Lithium’s Sonora project earlier this year.

Volkswagen

The iconic German automaker has been engaged in a very public battle with Tesla for EV market domination. UBS analysts recently predicted that VW will match Tesla’s sales by 2022 and will sell 300,000 more battery electric vehicles than the EV giant by 2025.

In 2019 Volkswagen signed a 10-year agreement with Ganfeng Lithium to supply lithium from Ganfeng’s mines in Australia, among others. Lithium from Chile is also used in the company’s electric models, the company states.

Conclusion

The greenies have a dirty little secret they want to keep from you: sourcing the raw materials that go into electric vehicles, solar panels, wind turbines and other eco-friendly technologies, isn’t that green; in some cases, it’s downright filthy.

We’ve seen what has happened in China and Indonesia, where a lack of regulatory oversight over rare earths and nickel mining/ processing has led to environmental degradation, or the Congo, where political instability has allowed the proliferation of armed groups who control the mines and employ child labor.

Doubtless there are many other countries where shady mine operators dig up dirty energy and battery metals for profit, with little regard to the consequences — a practice that is being encouraged by higher commodity prices.

Many more new mines will need to be build and existing mines will have to produce more. A lot of the “low-hanging fruit” has already been picked. The minerals left are often found in remote areas far from the prying eyes of government officials, or in countries that lack the appropriate legal and environmental protections.

The switch to green has birthed a lot of charlatans — companies and nations that are greenwashing their products and processes to stay ahead of the competition.

China says it has found a way to make green nickel chemicals for EV batteries from nickel laterite deposits in Indonesia that could help to alleviate the coming supply deficit in the metal that is essential to electric vehicle batteries.

Don’t be fooled. The process is extremely polluting, and “ocean tailings ponds” are anything but green.

Robert Friedland says Ivanhoe’s brand-new Kamoa-Kakula mine in the DRC will be among the largest and greenest in the world. Yet he hasn’t said when that will happen, only that the solution involves hydro-electric power. The DRC is so poor, only 13% of the population has access to power; the rest stumble around in the dark. Almost all the electricity flows to the mines, yet many still run on diesel-fueled generators. Flooding river valleys to make dams isn’t green; the process is highly disruptive to human and wildlife/ marine life populations. Until that choice is made, Friedland and co are placating the Congolese by smelting part of Ivanhoe’s copper output in a domestic refinery; a lot will be shipped to China — Citic Metal, and a subsidiary of China’s Zijin Mining, have agreed to buy 100% of the copper products from Kamoa-Kakula’s Phase 1 production.

Great. The copper gets shipped from Africa to China and smelted in a Chinese refinery using coal-fired power.

Tesla, Volkswagen, BMW and others have all been touting themselves as companies on the cutting-edge of the green energy revolution. Tesla made a promises to source locally that it couldn’t keep.

When push came to shove, Tesla said to hell with domestic mining, and signed offtake agreements with anyone but the US. That includes lithium from Australia and China – shipping costs to the environment using bunker oil and sea dumping waste must be enormous, cobalt from the DRC, and nickel from New Caledonia. How can a US-based company that sources its raw materials from the other side of the world, to make American cars, be called green?

How can Chile call its mining green, when seawater is being desalinated, at great expense and energy usage, and pumped hundreds of kilometers up to the mines in the Andes?

Environmental concerns are tied to social and governance issues. The DRC may not be committing environmental crimes like dumping tailings into the ocean, like Indonesia, but using child labor to mine coltan and cobalt, then selling into a so-called green supply chain, is just as bad.

In the rush to electrify the world economy, how much attention are we, as socially conscious investors, paying to green? To social responsibility? Not enough, imo. As investors, we should be mindful of greenwashing, spend the time investigating how companies are sourcing their minerals, and be willing to reward those who do things right.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.