Gold vs cash in a crisis

2019.12.20

Mattress stuffers or bullion holders? Who fares better in a crisis? North American investors are divided between those who believe the decade-long stock market bull is going to keep running into the 2020s, and investors who, wary of something terrible happening, are hoarding cash and gold.

The hopeful and the fearful

The beacon hopeful investors are following is best symbolized by analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, who describe current market conditions as “primed for Q1 2020 net asset melt-up”, based on continued monetary easing (central bank asset purchases, low interest rates) and a pending resolution to the trade war. A first-round trade agreement between the US and China was reached last Friday.

While roughly two in three investors polled in October said they see the global economy getting worse in 2020, in November a little more than half think the economy will improve next year.

Never mind that “melt-ups” typically happen at the end of asset bubbles and are usually followed by a significant stock-market correction. People planning to risk their money on equities next year are emboldened by strong stock market performances, as the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq Composite indices mount their latest concerted assault on all-time closing highs, powered by hope that the U.S. and China can forge a preliminary trade accord to resolve a prolonged battle over import duties, Yahoo Finance wrote in November.

Year to date, the three main stock market indexes have all posted impressive gains – as of Tuesday, the S&P had powered up 25%, the Dow was shown climbing 20%, and the Nasdaq had pushed a remarkable 29% higher than the start of the year.

Among wealthy investors however, a UBS survey published around the same time as the BoA prognosis found a much different temperament. The survey polling over 3,400 investors in 13 markets discovered these high-net-worth individuals are holding 25% of their portfolios in cash, much higher than the 5% normally recommended by UBS Global Wealth Management.

Some have liquidated up to half of their investment portfolios.

More alarming, 60% said they would think about increasing their cash holdings, and 79% said the economy is moving towards higher volatility. Clearly, these investors are reluctant to invest their hard-earned capital in equities, in case of an economic crisis they believe is coming.

While keeping one’s powder dry can be a good defensive move if things truly do take a turn for the worse, there are obvious risks, in the form of opportunity costs. Over time, cash-heavy investors will be paid next to nothing in interest. Cash hoarders will also take an immediate hit to their purchasing power should the US dollar fall.

Although the dollar has gained over the past five years due a number of reasons including low or negative interest rates (interest rates minus inflation) in other countries, and strong US stock market returns, that is far from the norm.

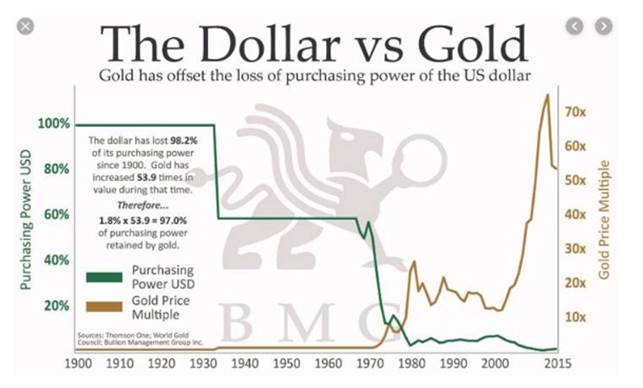

In the US there was an increase in inflation for every decade except the Depression when prices shrunk nearly 20%. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index indicates that between 1860 and 2015, the dollar experienced 2.6% inflation every year, meaning that $1 in 1860 was equivalent to $27.80 in 2015. The dollar has lost 98.2% of its purchasing power since 1900, while gold has become almost 54 times more valuable.

Barron’s quotes Tim Courtney, chief investment officer of Exencial Wealth Advisors, saying “Over the last 40 years, the dollar has done more declining than appreciating. A combination of factors, including the recent Federal Reserve rate cut, a soaring U.S. budget deficit, and lower gains for U.S. stocks, could put the dollar back on its long-term path of decline.”

The US dollar index has seen a fair amount of volatility this year and no clear trend. The buck against a basket of currencies fell to a low of 95.22 in January, rose to a high of 99.38 high in September, and only gained 1% year to date.

Mattress stuffers

Even more interesting than hoarding cash, instead of buying stocks, is what nervous investors are doing with it. As central banks print up to $100 billion per month to smooth volatility and goose economic growth, an equivalent amount in hard currency and precious metals is “disappearing”.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Banks are issuing more notes than ever and yet they seem to be disappearing off the face of the earth. Central banks don’t know where they have gone, or why, and are playing detective, trying to crack the same mystery.

For example in Australia, the number of bank notes issued relative to the size of its economy is near the highest in 50 years. Yet only about a quarter of these notes is used in everyday transactions, up to 8% are used in the shadow economy to avoid taxes or make illegal payments, and as much as 10% may have been lost – an astonishing sum amounting to AUD$7.6 billion (USD$5.2 billion).

Much of the $1.7 trillion in US cash circulating in 2018 went offshore, where the dollars were either stashed in bank accounts or invested in hard assets like real estate and gold. In 2016, a Fed economist estimated about three-quarters of $100 bills worth $900 billion, left the country.

WSJ points to a couple of strange cases of cash hoarding, including construction workers on Australia’s Gold Coast digging up $140,000 in buried bill packages; and a man in Germany who sued a friend that inadvertently burned 500,000 euros he had hidden in a faulty boiler while on vacation.

Gold hoarders

Investors are also turning to gold as a safe bet against market uncertainty. The yellow metal is the ultimate store of value, proven to have held its worth over time – unlike paper or “fiat” currencies which are subject to inflationary pressures and over the years, lose their value.

In laying out the case for gold, Goldman Sachs recently noted that 2019 is looking to break another record for central bank gold purchases – an estimated 750 tons – beating the record 651 tons accumulated last year. According to the World Council, 2018’s central bank gold haul was 74% more than 2017 and the highest amount since the gold standard ended in 1971.

Here’s where it gets weird. Goldman also discovered, over the past three years, 1,200 tons of gold flows worth $57 billion that mysteriously disappeared from the official record. Check out the charts below, showing the correlation between unexplained gold flows and increased global uncertainty (Figure 17) and how the amount of physical gold has soared higher than gold ETF holdings (Figure 18).

Gold beats cash, stocks

That got me thinking, in the event of a major meltdown such as the financial crisis or the dot-com crash, which fares better, cash or gold?

According to Forbes contributor Olivier Garrett, it’s a no-brainer – gold. In the table below Garrett highlights 2002 and 2008, the years corresponding to the dot-com crash and the financial crisis. In those years, all asset classes except cash and Treasury bills bled red ink. Treasuries gained a respective 10.3% and 5.2%, while cash showed a more modest 1.6% and 1.4% uptick.

He therefore suggests investors worried about the next downturn should own both T-bills and cash. How did gold do in those recessionary years? The precious metal was up 24.7% in 2002 and 2.7% in 2008.

Gold also beat stocks during the past two downturns. The chart below shows gold finishing the year ahead of the S&P 500 eight times since 2001. The only years that gold showed a negative return were 2012 and 2015 – corresponding to gold’s last bear market. In 2002, when gold gained 24.7%, the S&P 500 was down over 20%; its 2.7% gain in 2008 compares with the S&P’s awful -38%.

From early November 2008 to March 2009, the financial crisis market bottom, the S&P fell 30% while gold was up almost the same amount.

It’s common knowledge that gold zigs when the market zags. This has proven the case throughout history. The table below from GoldSilver blog depicts gold besting the S&P 500 in all but two of the S&P’s biggest declines since 1976. The metal’s only significant sell-off, 46% during the early 1980s, came just after its biggest bull market in modern history.

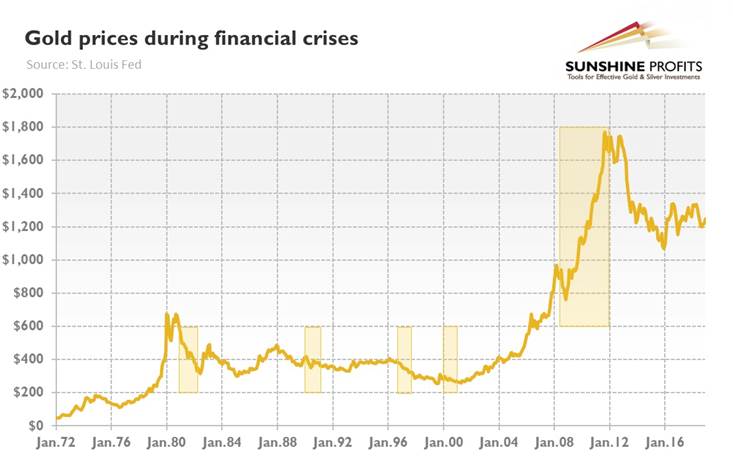

However it’s also important to recognize that gold doesn’t necessarily perform well at the beginning of financial crises. In the chart below from Sunshine Profits, during the most significant crises of the 20th century, in all cases gold declined initially. This pattern held true during the 1982 Latin American debt crisis, the Japanese stock market bubble burst in 1990, the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the 2000 dot-com bubble burst and the Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy in 2008. The latter event resulted in a brief leg down for gold before its relentless climb to a record-setting $1,900 an ounce over the next four years.

Finally, Motley Fool contributor Reuben Gregg Brewer uses the financial crisis to demonstrate how gold and stocks behaved. It’s not a directly inverse correlation. Between December 1, 2007 and May 30, 2009, the S&P 500 crashed 37%, while gold rose 24%. However one has to take a long view to realize gold’s gains. Brewer notes that when the recession first hit, gold went up nearly 30%, but at one point it dropped 10%. That kind of volatility might scare off some investors. But sticking with it over the length of the recession would have been wise; “overall, gold held its own at at time when stocks just kept falling,” states Brewer.

And while gold and the stock market generally show an inverse correlation, the World Gold Council found that between 1987 and 2010, only when stock prices moved dramatically ie. two standard deviations from the norm, did their relationship to gold turn negative. It seems that for investors to jump into gold when all hell is breaking loose on the markets, it needs to be a major crisis.

Wondering how much gold you need to gold to make it through a financial crisis? Another interesting table from the same source is shown below. Based on $1,300/oz gold, someone with $3,000 of monthly expenses would need 45 oz to last them through a two-year crisis, and 90 oz if the crisis drags on for four years. Ninety ounces equates to roughly 90 Gold Eagle coins. (1 coin= 1.0909 troy ounces). A standard gold bar held by central banks weighs 400 troy ounces.

The coming debt crisis

During the dot-com crash, it was up-start, overvalued Internet companies that hit the skids. During the financial crisis the US real estate bubble burst, taking several American banks and a few overseas ones with it. Many are predicting the next asset bubble to pop will be unsustainable levels of debt.

The US national debt, that is, the amount of debt held by the federal government, recently surpassed $23 trillion, having jumped $1.3 trillion in the 12 months leading up to November. The gross national debt, driven by Congressional borrowing, rose 5.6% up to the third quarter, compared to the same period last year, against nominal GDP of just 3.7%. In other words, debt is outrunning economic growth.

Wolfstreet asks a good question:

If the growth of the federal debt outruns the economy during these fabulously good times, what will the debt do when the recession hits? When government tax receipts plunge and government expenditures for unemployment and the like soar? The federal debt will jump by $2.5 trillion or more in a 12-month period. That’s what it will do.

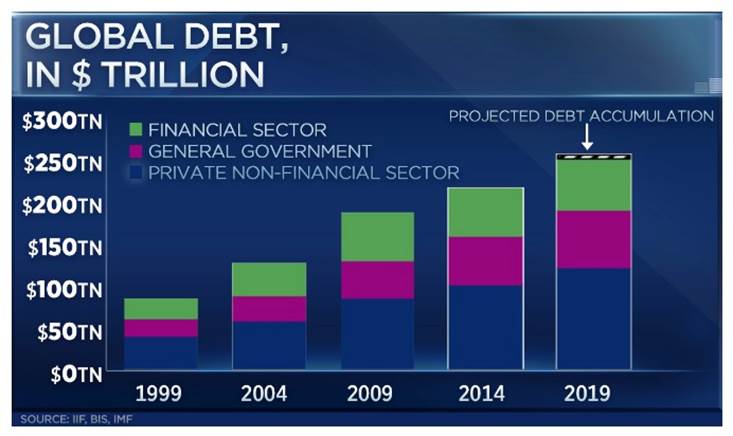

Worldwide, total debt including household, corporate and sovereign loans, during the first half of 2019 rose by $7.5 trillion to hit a record, $250 trillion, led by the US and China.

Encouraged by lower interest rates, governments went on a borrowing binge as they ramped up spending, adding $3 trillion to world debt in Q1 alone.

According to the World Bank, countries whose debt-to-GDP ratios are above 77% for long periods experience significant slowdowns in economic growth. Every percentage point above 77% knocks 1.7% off GDP, according to the study, via Investopedia. The United States’ current debt-to-GDP ratio is 106.5%.

According to its latest projections, the Congressional Budget Office says debt-to-GDP will reach 150% by 2047, well past the point where financial crises typically occur. The budget deficit is also likely to rise, nearly tripling from 2.9% of GDP to 9.8% in 2047.

This can’t go on forever. It’s not a stretch to envision a scenario whereby the world’s reserve currency, the US dollar, collapses under the weight of unmanageable debt, triggered say, by a mass offloading of US Treasuries by foreign countries, that currently own about $6 trillion of US debt. This would cause the dollar to crash, and interest rates would go through the roof, choking consumer and business borrowing. Import prices would skyrocket too, the result of a low dollar, hitting consumers in the pocket book for everything not made in the USA. Business confidence would plummet, mass layoffs would occur, growth would stop, and the US would enter a recession.

All the countries that sold their Treasuries would then face a major slump in demand for their products from American consumers, their largest market. Eventually companies in these countries would begin to suffer, plus all other nations that trade with the US, like Canada and Mexico. Before long the recession in the US would spread like a cancer, to the rest of the world.

It isn’t just sovereign debt that is being constantly added to, as governments around the world spend beyond their means. It’s also corporations and individuals.

According to the IMF, nearly 40% of the corporate debt of major economies including the US, China, Japan, Germany, Britain, France, Italy and Spain is at risk of default in the event of another global economic downturn.

In China, corporate bond debt defaults this year have surged almost 10 times 2014 levels.

Meanwhile the average North American is going deeper and deeper in debt – their confidence to spend fueled by continued low interest rates.

Earlier this year consumer debt in the United States hit $4 trillion for the first time. Total credit card debt surpassed $1 trillion, with the average American holding a balance of $4,923. A credit card survey quoted by CNBC says more than one third of Americans, 86 million people, are afraid they’ll max out their credit card when making a large purchase, which most considered to be anything over $100. The interest rate on credit cards has risen from 15.11% in 2017 to a current average of 21.4%. That is despite the US Federal Reserve lowering interest rates three times since August.

As incomes fail to keep up with spending, the difference financed by credit, the middle class is eroding – made worse by a drop in the number of middle-income jobs, through off-shoring and automation.

The share of adults living in middle-income households declined from 61% in 1971 to just 50% in 2015. Two-thirds of the 11% that were no longer middle class, migrated to upper-income levels, while a third became poorer.

And that gap continues to widen. The richest 400 Americans now control more wealth than the bottom 60% – it’s the greatest rich-poor divide since the 1920s.

A 2019 report by McKinsey Global Institute piles on more evidence of inequality getting worse. While the consulting firm notes the gap between developed and developing economies is shrinking, particularly with the rise of China and India, in many advanced economies, the trend is for the rich to pull away from the middling and the poor:

Yet politicians are oblivious to rising inequality and unsustainable debt. While Donald Trump touts the US economy as “the greatest of all time,” he is reportedly poised to sign a massive $1.4 trillion worth of government spending into law.

Here in Canada, Justin Trudeau’s Liberals were re-elected on a plan to double down on the nation’s deficit, which would peak at $27.4 billion next year – far exceeding the $14 billion deficit recorded in 2018-19.

The messages to the masses is obvious: it’s okay to spend beyond your means. In fact the US government prefers even lower interest rates and more quantitative easing, so it can go even deeper in debt, and companies can keep buying back more of their own stock in order to boost their earnings per share and the stock market keeps rolling right along.

Artificially low interest rates also hurt the average person; although unemployment is reduced, because companies borrow more and do more hiring, easier credit and low mortgage rates encourage over-spending and over-borrowing, sucking a lot of people into a debt trap from which it is hard to escape.

As one commentator aptly put it, “Essentially, the citizens become dreary rats on a treadmill while the government tells them they are winning the gold medal in the Olympics.”

Conclusion

The Plains Indians had an innovative way of hunting buffalo – find a very steep cliff and drive the poor, hapless creatures over it. This is quite a good analogy for the current, dangerously over-leveraged situation many developed economies find themselves in. Here the hunters are the governments and the buffalo running to their deaths are their gullible populations who have drunk the cool-aid of a consumptive lifestyle financed by endless debt.

The next bubble, the debt bubble, keeps building, fed by growing inequality, rapacious corporations who use tax breaks to buy back their own stock to artificially inflate their share prices, individuals who remain enslaved to the banks that reap enormous profits from them as they descend further into debt, and politicians who encourage the whole charade by cutting corporate tax rates, keeping interest rates near zero, and borrowing more through deficit financing to please the interest groups that keep them in power.

It’s no wonder that people have taken to hoarding gold – the only thing that matters when the shit hits the fan.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.