Get ready for extreme heat and its effects on crops, lives

2022.05.28

The climate on planet Earth is changing, and a lot faster than many had anticipated.

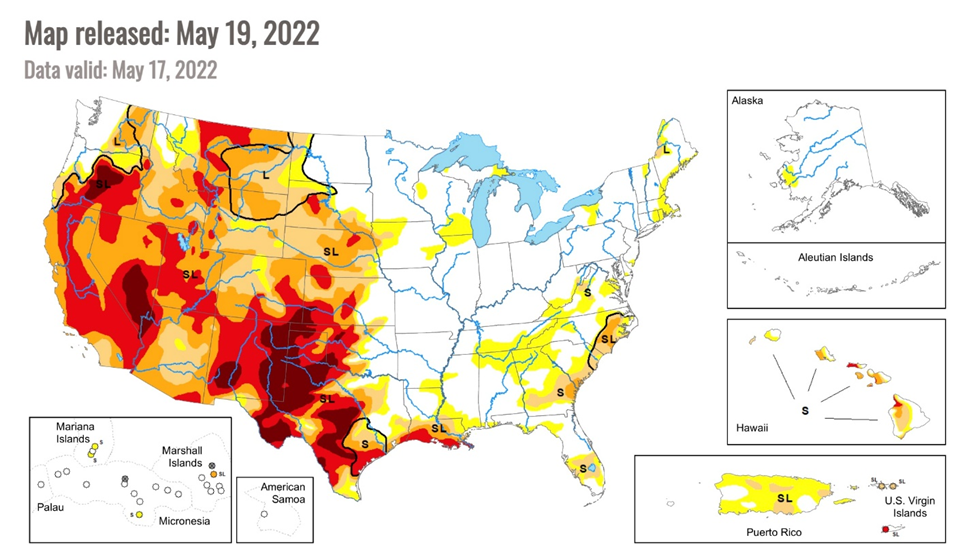

Droughts are impacting food production in Canada and the United States, lowering crop yields, and causing ranchers to cull part of their herds. Stubbornly high natural gas prices are being reflected in record-high fertilizer costs. Lake Mead, America’s largest manmade reservoir, and a source of water for millions, just fell to an unprecedented low.

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would on average reduce global yields of wheat by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

A new study showed more than a fifth of global food output growth has been lost to climate change since the 1960s, putting an estimated 34 million people on the brink of famine.

Among the agricultural commodities that have risen sharply due to a combination of climate change and the war in Ukraine, are the three most important food staples — rice, corn and wheat.

Scorching hot summer

On June 29, 2021, Canada’s highest-ever recorded temperature, 49.6 C, was reached in Lytton, BC. The day after, the village of 250 inhabitants was destroyed by fire — buildings razed to their foundations and the hulking wrecks of cars left smoldering.

The “heat dome” that covered much of western North America at the end of June, shattered temperature records, including Portland Oregon’s 46.6 C (116F) scorcher. It killed 595 people in British Columbia and caused more than 600 deaths in Washington and Oregon. An attribution study quoted by Climate Brief said the extreme heat would have been almost impossible without climate change.

But it wasn’t the only hot weather event. A persistent heat wave across Siberia helped fuel wildfires all summer, with temperatures hitting an unthinkable 48 C. Pakistan, northern India and parts of the Middle East were also seared by high temperatures surpassing 52 C in places.

Britain and Europe weren’t spared either, with normally mild Northern Ireland reaching a record 31.4C in July, and seeing the first “extreme heat warning” issued in the UK. Between 400 and 800 people are said to have died from heat-related causes.

In mid-August, another heatwave blanketed parts of the Mediterranean, including Spain, Italy, Greece and Tunisia, where a record-breaking 49 C caused power failures.

Although Western Canada has experienced an unusually cold & wet spring, there are indications we are in for another long, hot summer.

According to the Old Farmer’s Almanac, via CTV News, much of the country is in for a “sizzling summer” with “very warm, dry” conditions expected for parts of B.C.

The province has already seen an early start to the wildfire season, with more than two dozen blazes reported in April. While Environment Canada says it’s too early to tell what the fire season will look like, heat events are expected to become more common, year after year.

2021’s prolonged stretch of hot weather in southern British Columbia saw tinder-dry forests burning for months. Out-of-control wildfires, evacuation orders, and dangerous to breathe smoke that blankets communities for weeks, are now annual events in the BC Interior. According to the CBC, nearly 8,700 square km were burned in 2021 due to wildfires, making it the third worst year on record.

The BC government is planning to spend over half a billion dollars on new wildfire prevention resources over the next three years, after blowing an $801 million hole in its budget last year, one of the costliest wildfire seasons in BC history.

Record heat in India

Western Canada’s delayed spring is in direct opposition to what is happening in India; temperatures have soared to near 50 degrees C across almost the entire country of 1.3 billion people.

March was the hottest in 122 years, and according to the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), in northwest India the average maximum in April was 35.9 degrees C, 3.35 degrees above normal. Central India’s average high was 37.78 C, edging out the previous record of 37.75, set in April 1973.

But it’s not the record-breaking highs that are most concerning to climatologists. It’s the number and severity of extreme heat events. Severe heat has been reported over large parts of India since summer began in March. According to Indian Express, a total of 146 instances of heat wave/ severe conditions were recorded in April, the most since 2010. The average high for the country last month was 35.05, 1.12 degrees higher than normal and the fourth highest average since 1900.

While India is no stranger to heat waves, often experiencing days of intense hot weather ahead of the monsoon season that provides needed rains, this spring has been different.

“This heat wave is quite unusual,” Aditi Mukherji, a principal researcher at the International Water Management Institute out of New Delhi, told CBC News. “Heat waves are common in India, but never so early. Then, heat waves are [normally] localized, but this time, it is widespread almost all across [the country].”

A recent study found that climate change made the current heat wave in India and Pakistan more likely. (A glacier burst in Pakistan, sent floods downstream, and the early heat scorched wheat crops in India, forcing it to ban exports.)

Analyzing historical weather data, the World Weather Attribution Initiative found that heat waves impacting a large geographical area are generally once in a century events. But the current level of global warming has made such heat waves 30 times more likely.

Another analysis by the United Kingdom’s Meteorological Office said the heat wave was made 100 times more likely by climate change, with scorching temperatures likely to re-occur every three years.

Among the repercussions of the current South Asian heat wave, a spike in electricity demand for cooling depleted coal reserves, resulting in power shortages affecting millions. At least 90 people are said to have died in India and Pakistan, though that number is likely to be under-stated. The last major heat wave in 2015 killed an estimated 3,600 between the two countries.

CBC notes that South Asia is the part of the world most affected by heat stress, being home to more than a third of the world’s population living in areas where extreme heat is rising. Impacts are especially felt by the poor, who often live in crowded slums that lack access to fresh water and cooling equipment.

As for what is causing the heat wave, research scientists say it is a combination of climate change — i.e., a consistently warmer Middle East and Mediterranean blowing hot winds over to the Indian subcontinent — and the La Nina weather phenomenon.

The latter happens when colder waters persist in the Pacific Ocean, affecting global weather patterns. This year, it set up a pressure pattern that resulted in a colder than normal winter, but a warmer spring because warm air is funnelling down into peninsular India. The other factor is a warming Arctic, with higher-temperature air moving southeastward into Pakistan and India.

The bad news for the region is that more heat waves are a near certainty. In its most recent report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) found that “more intense heat waves of longer durations and occurring at a higher frequency are projected with medium confidence over India and Pakistan.”

The effects on cities are expected to be particularly potent. In Kolkata, India, 1.5 degrees of warming above pre-industrial levels (we are currently at 1.1 degrees) would see heat equivalent to the 2015 record heat waves every year. Karachi, Pakistan would see it about once every 3.6 years. With 2 degrees of warming, “both regions could expect such heat annually,” the panel wrote.

Heat and agriculture

Along with discomfort and a spike in electricity usage, causing blackouts, the heat wave has also hit India’s agricultural sector hard. The pre-monsoon showers are missing and the high heat on top of that makes India’s wheat crop particularly susceptible. The country is the world’s eighth-largest wheat exporter but there is talk of further restricting wheat exports. Power shortages not only restrict farmers’ ability to cool themselves; they also reduce the availability of electricity to irrigate fields with electric tube wells and pumps. The result is more hardship to a sector that is already in bad shape.

According to The Conversation, The agricultural sector only contributes about 15 per cent of national income, yet more than half of India’s workers depend on it for their livelihood. The vast majority are small farmers, sharecroppers and landless laborers who struggle to stay afloat on precarious wages, shrinking plots and the vagaries of the monsoon.

The costs of production continue to rise. Growing indebtedness, either to informal moneylenders or formal banks, has tragically compelled thousands to take their lives over the past two decades.

While farmers in North America are better off, they are also struggling with heat waves and drought.

An extended drought since 2000 in the Colorado River Basin — which includes bits of seven western states and a part of Mexico — has made it impossible for the country’s biggest reservoirs, Lake Mead in Nevada and Lake Powell straddling the border of Utah and Arizona — to recharge fully.

This is a huge problem, considering that the Colorado River provides water for more than 40 million people including major US cities Las Vegas and Los Angeles.

According to the CBC, the dramatic drying in 2021 deepened the American West’s 22-year “megadrought” so much that it is now the driest in 1,200 years (the previous megadrought was in the late 1500s). A study in ‘Nature Climate Change’ journal says the current drought shows no signs of easing.

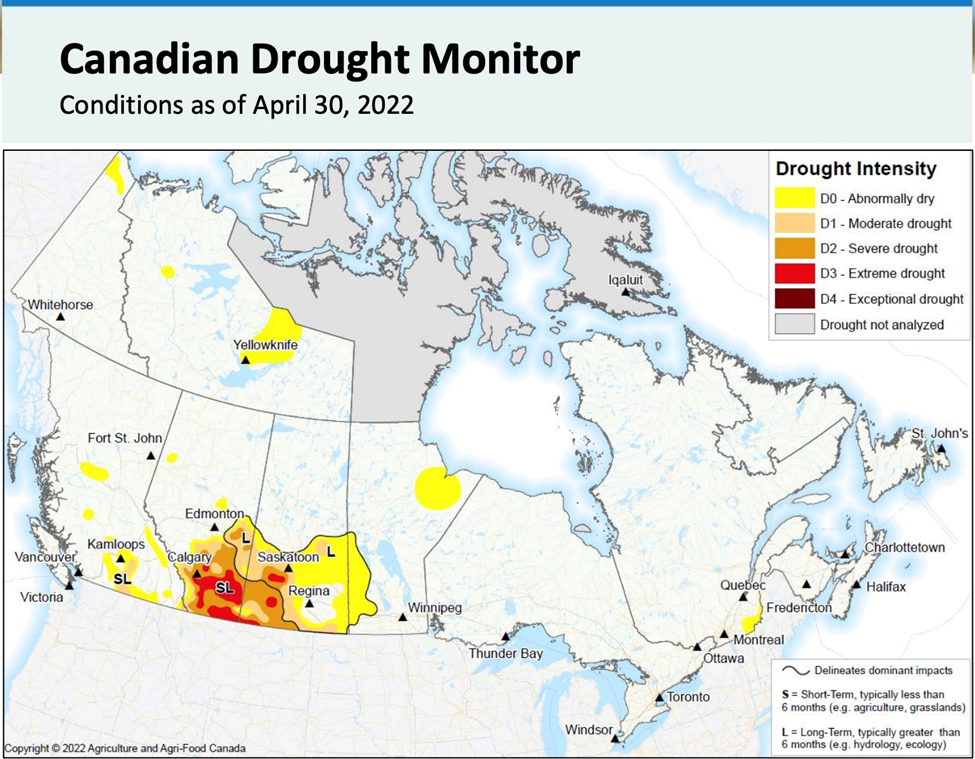

A second map shows much of the Canadian Prairies in drought, as of April 30, with the driest areas (Severe drought in brown and Extreme drought in red) straddling most of southern Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Abnormally dry areas depicted in yellow extend into British Columbia, northern Manitoba and the area around Yellowknife, NWT.

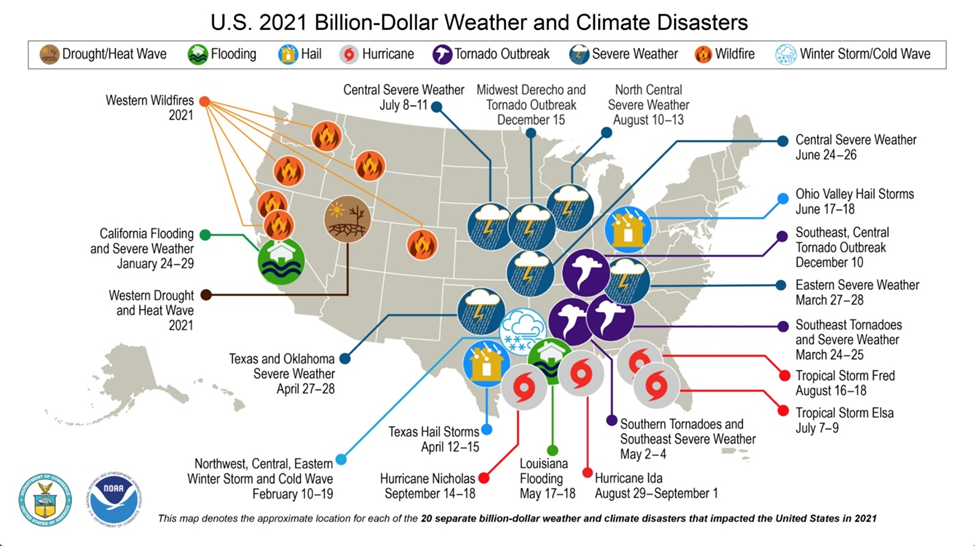

Food production in the United States, like all of the world’s agricultural regions, is weather-dependent, but last year’s natural disasters were particularly impactful.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), between hurricanes, wildfires and floods, 2021 was the third-costliest disaster year ever, with an estimated $145 billion in total economic losses, behind only 2017’s $346 billion and 2005’s $244 billion. Over 680 lives were lost in these extreme weather events.

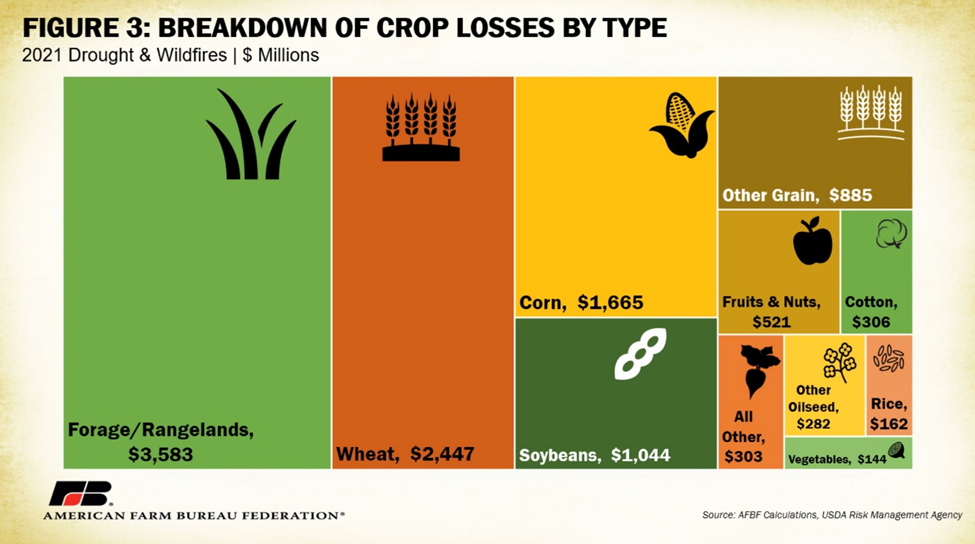

Total crop and rangeland losses were pegged at over $12.5 billion, of which drought and wildfires alone accounted for over $3.3B in losses that were not covered by Risk Management Agency (RMA) programs. Crop loss estimates from the American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) do not include infrastructure damage, livestock losses, or losses to horticulture and timber.

Among the areas worst hit, North Dakota faced over $2.4B in incurred losses, primarily due to $500 million in damages to wheat, soybeans and corn due to extreme drought conditions.

Texas was a close second with $2B in incurred losses due to a variety of bad weather including the February 2021 deep freeze, widespread drought, a major hailstorm and Hurricane Nicholas. Damages were linked to rangeland and forage, with $300 million involving the destruction of grapefruit and orange groves.

South Dakota suffered drought-induced losses of over $100 million each in corn, soybeans, wheat and forage.

In fourth place was California which, also plagued by drought, saw over $1 billion in damages including half a billion in fruit and nut losses, such as $125 million in almonds and over $150M in grapes.

According to AFBF’s market intelligence,

Reductions in hay stores and abysmal forage conditions forced many farmers and ranchers to liquidate cows early or pay upward of $400/ton for hay shipped across state lines. Wheat, heavily grown in the upper Plains region in states like North Dakota, Montana and Idaho, also fell victim to severe dry conditions.

Forage and rangeland saw the most significant losses ($3.6 billion), followed by wheat, corn and soybeans, as shown in the graphic below. The numbers were similar whether talking about all natural disasters (Figure 2) or just for droughts and wildfires (Figure 3). The latter made up over 87% of total US crop losses in 2021.

Despite President Biden signing into law an extension of disaster assistance programs last September, many farmers and ranchers have yet to see a penny:

As of March 9, no payments have been made for 2020 and 2021 losses and applications have not opened for producers to enroll. This means producers who faced disaster-related crop losses in early 2020 have waited over two years for support.

The AFBF concludes that “already in 2022, farmers and ranchers are experiencing severe drought.”

A research team at the University of Colorado Boulder found that heat waves, which are expected to become more frequent and more intense, could cause up 10 times more crop damage than is currently projected.

A 2020 academic paper published in the journal ‘Plant Science’ provided a summary of the current literature on crop responses to extreme heat, focusing on perennial agriculture in California.

Among the research team’s key findings, edited here for brevity:

- Extreme heat events will challenge agricultural production and raise the risk of food insecurity.

- Detrimental heat exposure occurs primarily during the cool season, when anomalously warm temperatures occur during dormancy and/or bloom.

- Exposure to anomalous warmth during dormancy can delay or prevent chill accumulation, which can cause delayed or asynchronous bloom, a compressed flowering and pollination window, delayed vegetative development and altered leaf morphology, fruit set failure, and reduced yields. The 2015 California pistachio crop was devastated by a warm winter and subsequent insufficient chill, which resulted in more than $180 million in losses.

- Research suggests that temperatures above ∼30°C during flowering can be detrimental to the hormone production needed for cell division and differentiation.

- The combination of heat and water stress has great potential to affect crop yield, size, and quality. For example, moderate-to-severe water stress during nut development can reduce yield, size, and quality in almond and pistachio. Similarly, modeled effects of water stress in peach show reductions in fruit size.

- Research has shown that temperatures > 35℃ may slow physiological processes and can scar, crack, or discolor berries, irrespective of water application. Extreme heat can also decrease wine grape berry size and fresh weight. Further, extreme heat exposure during ripening can influence sugar accumulation, phenolic development, total phenol and anthocyanin concentrations, soluble solids, and proline and malate concentrations – all of which can shape the winemaking process and ultimately wine quality characteristics such as color and aroma.

- As climate change increases average and extreme maximum cool season temperatures, the reduction in chill accumulation across much of California may reduce areas with suitable chill for some of the state’s high-value perennials. For example, for cultivars requiring > 700 chill hours, ∼50-75% of California’s Central Valley may not receive reliably sufficient chill for peach cultivation by mid-century, and as little as 2–10 % of the region may remain suitable by the end of the 21st century. Similarly, the high chill requirements of pistachios and walnuts may eliminate their cultivation in California as early as 2060.

Wet bulb temperature rating

When temperatures are rising so fast that extreme heat becomes a common occurrence in several parts of the world including our own (Western Canada), plant growth is stunted, leading to lower crop yields and in worst cases, the destruction of the entire crop.

In a rapidly warming world, it’s worth considering what this means for human health.

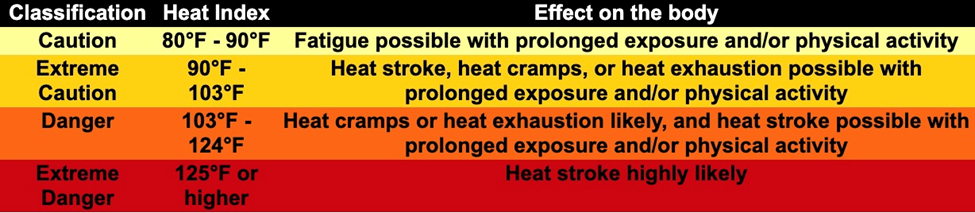

People are generally comfortable living and working in temperatures up to about 80 degrees Fahrenheit. The heat index is what the temperature feels like when relative humidity is combined with relative humidity. Between 80 and 90 degrees F, fatigue is possible with prolonged exposure and/or physical activity. From 90 to 103, heat stroke, heat cramps or heat exhaustion are possible. The danger zone is entered @ temperatures between 103 and 124, with extreme danger happening when it gets to 125 F (51 Celsius) or higher.

In fact, our current heat measurements may be underestimating the dangers of extreme heat to the human body. Meteorologists are therefore turning to the “wet bulb globe temperature” for a more accurate reading.

Basically a more nuanced version of the heat index, the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) takes into account not only the air temp and humidity, but the wind speed, sun angle and solar radiation levels.

Between 80 and 88 degrees Fahrenheit WBGT, working in the sun for more than 45 minutes put the body under serious stress. About 88 WBGT, the window of safety closes to 20 minutes. Above 90, being active in the heat becomes dangerous after 15 minutes, and reaches a point in the 90s where you shouldn’t be doing anything outside.

The latter point is important. According to Popular Science, This is not an issue of simply not exercising or working outside. Wet bulb temperatures this high can kill people who are simply sitting around doing nothing, if they lack access to air conditioning and water.

This is because, above a certain WBGT, the human body loses the ability to cool itself down. The body’s normal cooling mechanism, the way it sheds heat, is by sweating. The upper level of sweaty skin is about 95 WBGT; beyond that, skin loses the ability to carry heat from the body and evaporate it through sweat. Wet bulb temperatures above 95 are therefore extremely dangerous, and sustained temperatures above 98 are considered fatal. The body literally cooks to death from within.

It was previously thought that wet bulb temperatures very rarely exceeded 91 degrees F, but a 2020 study quoted by Popular Science found that this point has been crossed many times. Among the regions that have experienced this kind of heat, are South Asia, the coastal Middle East, and coastal southwestern North America.

As an illustration of how dangerous this level of heat is, consider: the heat wave in Russia in 2010 and those across Europe in 2003 had wet bulb temperatures below 83 F. Around 55,000 people died in Russia and 35,000 were killed in Europe during these heat waves.

Imagine how many people, many of whom lack access to fresh water and air conditioning, could be killed if wet bulb temperatures push into the 90s, which is entirely possible the way global warming is going?

Nearly 600 people died in British Columbia alone during last year’s “heat dome”, when temperatures rose above 40 degrees C from late June to early July. Almost three quarters were over the age of 70, and 99% died after being overcome by heat in a home or a hotel.

Many were shocked at how high in latitude the heat dome stretched. While the Lower Mainland communities of Vancouver, Surrey and Burnaby saw the most deaths, Prince George, located further north, in a much cooler climate, had 12.

Conclusion

We’ve always known that heat exposure can be dangerous, even fatal, but it is only recently that the northern hemisphere has experienced the kind of heat normally seen in the southern hemisphere.

As global warming continues unabated, the wet bulb temperature rating is due to become a more accurate means of gauging extreme heat; using it could save lives.

Meanwhile, our global food supply, already in jeopardy due to the war in Ukraine, and drought conditions in many parts of the world, is likely to become even more tenuous.

Remember, heat waves, which are expected to become more frequent and more intense, could cause up to 10 times more crop damage than is currently projected. The United States experienced about $12 billion in crop losses last year, of which 82% was due to drought and wildfires.

The remarkably small global resource of fresh water — only 0.007% of water is available for drinking, feeding or fueling — is in serious peril due to climate change, increased demand and polluted water supplies.

According to the UN, demand for water is expected to grow 55% by 2050, with most of the need (70%) driven by irrigation, to feed the expanding global population, expected to hit 10 billion by 2050. Water for energy use is forecast to rise by 20%.

The supply won’t be enough to satisfy everyone. By 2025, 1.8 billion people will live in areas where water is scarce, and two-thirds will be residents in water-stressed regions, reports National Geographic. Read more

Between extreme heat and a lack of fresh water, areas of planet Earth may soon become inhabitable, putting an even greater strain on existing finite natural resources, and increasing competition for them.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.