‘Friend-shoring’ threatens Western metal supplies

2022.07.06

In George Orwell’s book ‘1984’, the world is divided among three superpowers, whose continuous struggle for global dominance plunges the world into a never-ending conflict.

Oceania, Eastasia and Eurasia, with their large spheres of influence, closely mirror how the Grand Alliance of the US, the UK and the Soviet Union planned the defeat of Nazi Germany during World War II.

The novel was written 73 years ago, but it has contemporary relevance, in that the world order is again fracturing along ideological, political, military and economic lines. The catalyst isn’t a war, but rather, a gradual realization that the benefits of globalization aren’t what we thought they were, when considered in the context of the US-China trade spat and continuing tensions between the two superpowers; the covid-19 pandemic which highlighted the West’s dependence on China for medical supplies; Britain’s exit from the European Union; the rise of US protectionism first with Trump and now Biden, who hasn’t removed Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods and has additionally slapped sanctions on Russian banks and individuals along with a beefed-up Buy American rule; and the war in Ukraine, which has not only deepened geopolitical tensions but shown the fragility of European natural gas supplies, 40% of which comes from Russia.

Indeed the escalation in trade disruptions over the past few years has cumulatively called into question the vision of a globalized economy. In response, some US officials and one Canadian politician have introduced a new term to the diplomatic lexicon: friend-shoring.

What is friend-shoring?

“Friend-shoring” presumes a world divided between free-market economies and countries that align with authoritarian regimes. First there was “offshoring”, which transferred manufacturing (and jobs) overseas to save money on labor and to maximize profits. Then came “onshoring”, the idea of bringing production home to reduce supply chain disruptions and to repatriate US jobs. Friend-shoring, or ally-shoring, is similar to onshoring except that it’s not restricted to domestic production. Reliable friends are also deemed okay as sources.

The idea is for a group of countries with shared values, and at a similar stage of development, to source raw materials and to manufacture goods, from within that group. The goal is to prevent less like-minded nations from exploiting their comparative advantage, or in some cases, their monopolies, in key raw materials, technologies or products.

“[Countries] that espouse a common set of values on international trade … should trade and get the benefits of trade,” US Treasury Secretary (and former Fed chair) Janet Yellen said alongside Canadian Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland at an event by Canada 2020, a think tank. “The idea is to ensure the US and its allies have multiple sources of supply and are not reliant excessively on sourcing critical goods from countries, especially where we have geopolitical concerns.”

According to Freeland, the assumption that the world’s countries could all “get rich together” through trade — the consensus during the 1990s, apexed by China being admitted into the World Trade Organization in 2001 — has proven overly optimistic.

“I really believe that Putin’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has shown us all: it didn’t work,” Freeland said of the world’s attempt to embrace free trade. “That era is over. We need to figure out what replaces it.”

Clearly the target is China and Russia. The US wants to reduce dependence on authoritarian regimes like China that supply the majority of the world’s rare earths and magnets, and dominate the production of several battery/ electrification metals including copper, zinc, tin, lithium and graphite; and diversify away from Russian suppliers of critical commodities such as energy, food and fertilizer. In some cases, like semiconductors, the goal is to divvy up supply between friendly nations. For example the US has recently begun engaging with South Korea to diversify chip production away from Taiwan, which is its no. 1 supplier but faces a security threat from China.

Friend-shoring isn’t just theoretical; the term has made its way into a 250-page report released by the Biden administration in June, titled ‘Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-Based Growth’.

In a blog post for the Brookings Institution, authors Elaine Dezenski and John Austin say that “ally-shoring” will strengthen the economies of the US and its allies and that “working together to rewire supply chains and co-produce high-tech products in emerging sectors will serve to rebuild bruised alliances and US global economic and political leadership, as well as check China’s bid to extend their own authoritarian economic and political model across the globe.”

The term may have even sparked a rare bipartisan agreement in Washington, with the Senate’s approval of a $250 billion bill to build US leadership in key technologies such as computer chips, 5G, artificial intelligence and quantum computing, Bloomberg wrote recently.

Who wins?

Countries most likely to benefit from friend-shoring are the world’s most developed economies including European Union members, the United States, Japan, Canada, the UK and Australia. Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam and other southeast Asian nations would also probably do well, as production plants, jobs and investment move to countries deemed trust-worthy by the US and its allies. Diversifying supply chains will help businesses to be more resilient to external shocks like wars, insurrections or global health emergencies.

Who loses?

Regimes like China that the US leadership sees unfairly supporting their domestic industries, and nations like Russia that violate international norms, would be hit economically, as jobs and investment shift to other countries considered Western-friendly.

The impact

Here is where the rubber hits the road.

During a time when Russia brazenly invades a neighbor and China repeatedly wields its economic clout, trading only with countries with shared values and economic interests appears to make a lot of sense.

Friend-shoring sounds good, but how beneficial would it really be? An AOTH analysis found that friend-shoring’s harmful effects far outnumber its benefits.

The first criticism is that it risks being exclusionary and elitist, and can lead to protectionism and higher costs.

To understand this, we first need to learn a little economics. The theory of comparative advantage was pioneered by David Ricardo, a 19th century economist. It means that trade works best when it is guided by the notion that a country should only manufacture and export goods that can be made at a lower cost than its competitors. All other considerations, like politics, human rights, etc., should be set aside in the name of maximizing prosperity. A country X is said to have comparative advantage when it can make a product cheaper than country Y.

Friend-shoring runs counter to free-trade principles like comparative advantage, that underpin the current world order. Let’s say I need to source iron blocks. The cheapest place to buy them, and the country that has comparative advantage in iron blocks, is Afghanistan (I don’t know who actually makes the lowest-cost iron blocks, this is just an example). But Afghanistan has a poor human rights record, and is currently ruled by the Taliban, so it doesn’t make my “friends” list. Instead, I decide to buy them from Luxembourg, not because its iron blocks are the cheapest, but because Luxembourg is part of NATO. Who wins in such an arrangement? Definitely not Joe and Jane Sixpack.

The whole system of world trade could quickly become exclusionary and elitist. By only trading with developed countries, those with high labor standards, for example, citizens will have to pay for those higher standards, and therefore, higher-priced products. Countries would also be tempted to protect their domestic industries, again resulting in higher costs to consumers. This is during a period of rampant inflation.

Friend-shoring forces companies to pick sides and can unintentionally forge bad blood with other countries, one commentary argues.

Building resilient friend-shoring supply chains comes with high costs, including the steep price tag of relocating manufacturing operations to another hemisphere.

Economists argue that picking trade partners for geopolitical reasons could create a world of antagonistic blocks, similar to Orwell’s imaginary world, or the Cold War. As the Wall Street Journal maintains, the global economy could split into two hostile camps, the United States and China, thus hurting growth and accelerating inflation.

Beata Javorcik, chief economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, calculates that the creation of a two-bloc world would lead to a 5% loss of global economic output over a 10- to 20-year period — equivalent to roughly $4.4 trillion.

Also, the question of whether to label a country friendly or unfriendly is highly subjective. Should India be excluded because it is buying Russian oil when other countries are boycotting it? Hungary is in NATO but its leader, Viktor Orban, is a far-right nationalist. If Trump, or some other US populist, returns to power in 2024, could US allies exclude the United States from their friend-shoring clique?

The main disadvantage of friend-sourcing though, comes down to who is excluded. Globalism has many flaws, but one thing it can be credited for is lifting millions out of poverty, by giving poor countries the opportunity to access wealthier markets.

“Friend-shoring would tend to exclude the poor countries that most need global trade in order to become richer and more democratic,” Raghuram Rajan, the former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund and former governor of India’s central bank, said in a recent commentary published by Project Syndicate. He adds,

“The benefits of a global supply chain stem precisely from the fact that it involves countries with very different income levels, allowing each to bring its comparative advantage to the production process – PhD researchers from one, for example, and unskilled assembly-line workers from another.

“Friend-shoring would tend to eliminate this dynamic, thereby increasing production costs and consumer prices. While some labor unions would welcome the reduced competition, the rest of us would regret it.”

The Wall Street Journal agrees that friend-shoring appears to diminish the economic impact of developing nations. According to WSJ, The “non-friendly” countries —those that voted against Russia’s suspension or abstained [from suspending Moscow from the UN Human Rights Council] — include China, India, Brazil and Mexico. In total, they account for 35% of all goods imported by members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the group of rich countries that includes the US and most of its closest friends.

Rajan also notes that friend-shoring would increase the risk of countries that previously traded with developed countries, of becoming failed states, and fertile ground for terrorism. Such countries would likely be forced to trade with the very regimes that the West is trying to prevent from gaining an advantage: China and Russia.

Let’s be clear: when it comes right down to it, friend-shoring would only involve a small group of developed nations, let’s say 20% of the world’s 195 countries. The other 80% of the globe’s 7. 7 billion population would be frozen out of this “rich man’s club”.

Moreover, friend-shoring is really just another way for the United States to control the means of production, for the country to source raw materials cheaply (no different from the way it exploits Canada’s oil and minerals) and to bring manufacturing back to America.

Think of it this way: for the past two years, the United States has been struggling to put their supply chain issues right, now the administration appears to be saying to businesses, “Stop what you’re doing. Now we only want you trading with nations friendly to the United States.” To hell with globalization. It’s also rejecting 80% of the world to trade with, leaving their economies to stagnate, their citizens without markets to sell their goods into, instead buying all American raw materials from pro-US sources, and manufacturing them either in the United States, or in friendly countries.

I’m not alone in this view. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, director of the World Trade Organization, says countries should resist the urge to tear up the trade blueprint they’ve so carefully crafted over the past few decades, telling the Financial Post, instead of choosing to “retreat into ourselves, make as much as we can ourselves, grow as much as we can ourselves, we should reform the WTO that underpins it and upgrade its rules to deal with 21st century challenges.”

Note that Nigeria was Canada’s largest bilateral partner in Africa in 2021, providing the country with minerals, fuels and oils, rubber, cocoa and lead worth $2.1 billion in total. But under a friend-shoring policy that prioritizes human rights, Nigeria would likely be excluded.

Also consider how some of the world’s fastest-growing economies that are in Africa, would be denied a trading relationship with Canada, the United States, the EU and Japan, to name a few highly developed economies, should friend-shoring become official policy.

In a previous article, we pointed out that since 2000, at least half of the countries in the world with the highest annual growth rate have been in Africa. By 2030, 43% of Africans are projected to join the ranks of the global middle and upper classes. By that same year, household consumption in Africa is expected to reach $2.5 trillion, more than double the $1.1 trillion of 2015, and combined consumer and business spending will total $6.7 trillion.

According to the ‘Movers’ ranking by US News, among the world’s 10 fastest growing economies, three are in Africa. United Arab Emirates was rated #1, Egypt was third and Saudi Arabia was 10th.

‘Friendly’ critical minerals coalition

An example of friend-shoring put into practice, is the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), formed in June as a sort of “metallic NATO”. Members include the United States, Canada, Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the European Commission.

Theoretically open to all countries that are committed to “responsible critical mineral supply chains to support economic prosperity and climate objectives,” the MSP aims to help “catalyze investment from governments and the private sector for strategic opportunities … that adhere to the highest environmental, social, and governance standards,” reads a statement from the US State Department.

In fact, the MSP is defined more by who is not on the list — China and Russia. Reuters metals columnist Andy Home makes the following points about the MSP as it relates to friend-shoring:

- China’s dominance of key enabling minerals such as lithium and rare earths is the single biggest reason why Western countries are looking to build their own supply chains. Russia, a major producer of nickel, aluminium and platinum group metals, is now also a highly problematic trading partner as its war in Ukraine that the Kremlin calls a “special military operation” grinds on.

- The MSP marks a new chapter in the critical minerals story. The pressure to decouple from China has been growing for several years but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has concentrated minds. While the immediate focus is on Russia’s role in the energy sector, there is a recognition that critical minerals could be next.

- The United States and Europe have realised that they can’t build out purely domestic supply chains quickly enough to meet demand from the electric vehicle transition. The answer is “friend-shoring”. If you can’t produce it yourself, find a friendly country that can.

- The process was already well underway before the US State Department announced the formation of the MSP on June 14. US and Canadian officials have been working closely as Canada fleshes out a promised C$3.8 billion ($3.02 billion) package to boost production of lithium, copper and other strategic minerals. European Commission Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič has just been in Norway to seal “a strategic partnership” on battery technologies and critical raw materials. [Norway is part of the EEA, the EFTA and the Schengen Agreement, but not of the EU].

- The Pentagon is getting in on the friend-shoring trend too. It has asked Congress to amend the Cold War-era Defense Production Act (DPA) to allow it to invest directly in Australia and the United Kingdom. The DoD is investing $120m in a new plant for heavy rare earths separation. It has chosen an Australian company as its partner. Lynas Rare Earths will supply the plant in Texas with mixed rare earths carbonate from its mine in Western Australia as well as working with third-party suppliers “as they become available,” it said. The plant is due to become operational in 2025 and Lynas and the DoD are already working on a complementary light rare earths separation facility.

- As for China and Russia, “we’re still going to have a relationship with countries outside this closest circle but it’s going to be a … relationship that has less trust at its heart,” according to Chrystia Freeland. The days of unlimited Chinese mining investment in countries such as Canada and Australia are probably over.

Copper, for example

The Minerals Security Partnership is a good idea, here at AOTH we’ve been saying for years that the West isn’t doing enough to secure supplies of critical minerals, so we’re behind it 100%. The problem is it’s too late. For the past two decades, China has been signing offtake agreements to procure the metals it needs to grow and modernize its economy, the second largest in the world behind the United States.

The first offtakes were for copper and iron ore, done with African countries in exchange for building much-needed infrastructure. Then it was lithium the Chinese were after, resulting in metal supply agreements with Australia, Chile and Argentina, for example. Currently China is building capacity for mining and smelting nickel to make lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles in Indonesia. China also has an offtake agreement with Ivanhole Mines’ recently started Kamoa-Kakula copper mine in the DRC, and through China Molybdenum, owns 80% of the Tenke Fungurume copper-cobalt mine, also in the DRC.

After 20 years of investing in overseas mineral deposits, China now has a lock on many of the world’s metals, or the processing of them. This includes iron ore, copper, lithium, graphite, cobalt, and rare earths.

According to the US Geological Survey, the United States is reliant on totalitarian regimes with dictators installed for life for 32 of 47 minerals — an eye-watering 70%! We are of course talking about China (23) and Russia (9).

For friend-shoring to work with respect to mining, all the friendly countries would have to have enough resources to trade among themselves. Unfortunately, the reality is that most of the metallic resources they want are controlled by regimes hostile to them.

Let’s take copper as an example. Of the identified copper that has yet to be taken out of the ground, about two-thirds is in just five countries: Chile, Australia, Peru, Mexico and the United States.

Last year the top 10 copper producers were, in descending order, Codelco, Freeport McMoRan, Glencore, BHP, Southern Copper, First Quantum Minerals, KGHM Polska Miedz, Antofagasta, Zijin Mining and Anglo American.

At first glance, it appears that a friend-shoring arrangement could be made between the top 10 producers who, apart from Zijin Mining (China), are all domiciled in North America, Western Europe, Latin America and Australia, as shown in the table above.

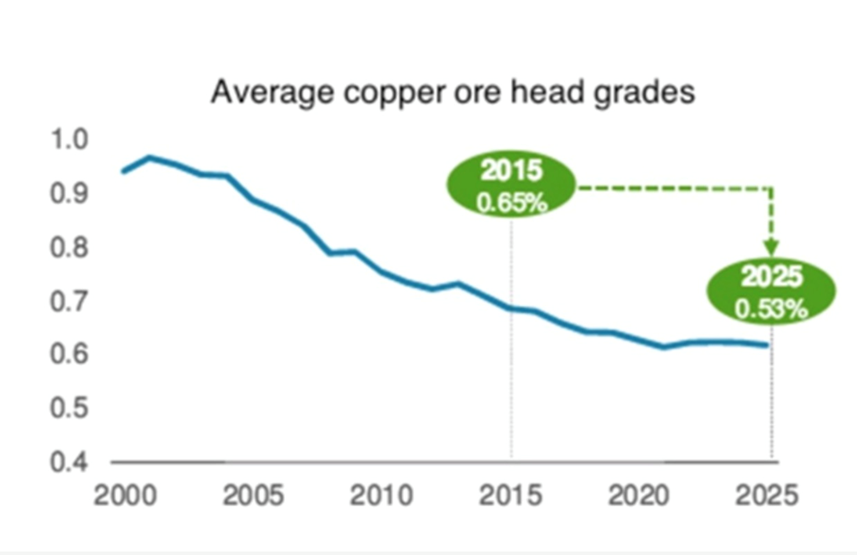

But the copper market is tight, based on a combination of factors including lower ore grades, droughts/ lack of fresh water, resource nationalism in top producers Chile and Peru, and a dearth of new discoveries in recent years. To avoid a copper shortage as early as 2025, billions will need to be spent on discovering new copper deposits.

However, AOTH research shows that new supply is concentrated in just five mines — Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC.

At Cobre Panana, nearly half of the 300,000 tonnes per year (tpy) production goes to Korea. Under a 15-year offtake agreement, Canadian miner First Quantum Minerals will ship 122,000 tpy of copper concentrates per year from Cobre Panama to South Korean copper smelter LS Nikko.

The Kamoa-Kakula copper project is a joint venture between Ivanhoe Mines (39.6%), Zijin Mining Group (39.6%), Crystal River Global Limited (0.8%) and the DRC government. Kakula reached commercial production on May 25, 2021, and while output is currently set for 200,000 tpy in Phase 1, a second phase would add 200,000 tpy and peak production would exceed 800,000 tpy.

Last year Ivanhoe signed two offtake deals, one with a subsidiary of its partner firm, China’s Zijin Mining; the other with Chinese commodities trader CITIC Metal, to sell each 50% of the copper production from Kakula — the first of two mines involved in the joint venture. In other words, 100% of Kamoa-Kakula’s Phase 1 production goes to China.

That leaves three mines in Chile — Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca’s “QB2” expansion. In 2016 BHP, the majority owner of Chile’s Escondida, the largest copper mine in the world, committed to spend just under $200 million to expand its Los Colorados concentrator. The expansion would help offset declining ore grades and add incremental copper production to reach an average 1.2 million tonnes a year over the next decade. BHP owns a 57.5% share in Escondida, Rio Tinto owns 30%, and the remaining 12.5% is owned by JECO Corp and JECO2 Ltd.

JECO is a Japanese joint venture between Mitsubishi Nippon Mining & Metals and Mitsubishi Materials Corp. It is not immediately clear whether any of Escondida’s production is bought by JECO Corp.

BHP recently commissioned a $2.46 billion copper concentrator plant that will extend the mine life of its Spence mine by 50 years.

The operation is expected to produce 300,000 tpy until at least 2026. Spence ownership is split 50-50 between BHP and Santiago-based Minera Spence SA.

Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 project is expected to produce 316,000 tpy of copper equivalent for the first five years of its 28-year mine life. In 2019 the Canadian company closed a $1.2 billion transaction whereby Tokyo-based Sumitomo Metal Mining and Sumitomo Corp will, through an $800 million and a $400 million contribution, acquire a 30% interest in project owner Compañia Minera Teck Quebrada Blanca S.A. (“QBSA”). Like Escondida, it is unclear whether the two Japanese companies will take a portion of QB2’s production, or whether they will simply share in the profits.

Summing up, our analysis shows that in two of the five mines where new copper supply is concentrated, there are offtake agreements in place with non-Western buyers. In the case of Kamoa-Kaukula, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project. Nearly half of Cobre Panama’s annual production goes to a Korean smelter under a 2017 offtake agreement.

Conclusion

If most of the world’s mine production is already going to China, either through offtake agreements, Chinese state-owned ownership of overseas mines, or mines partly owned by Chinese companies, the question is, how much can friend-shoring help the West to secure supplies of industrial metals needed for infrastructure buildouts, like copper, zinc, lead and aluminum, and the new green economy that demands electrification & decarbonization metals including copper, nickel, lithium, graphite and cobalt?

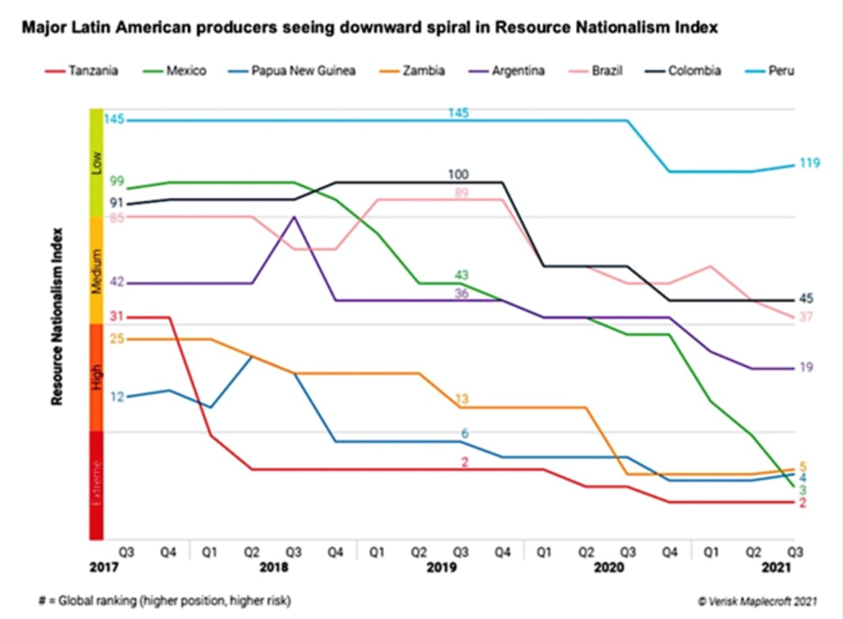

If your friends don’t have the minerals you need, and existing supply is owned by China and Russia (remember, according to the USGS, the United States is reliant on Russia and China for 32 of 47 minerals), the only alternative is to go out and find new mineral deposits. Problem is, there are no “new” places to go. All the low-hanging fruit has been picked and the deposits that are left are either in remote locations requiring billions of dollars worth of capital investments (power, water, roads, mineral processing), or are in jurisdictions where governments are prone to resource nationalism. We are already seeing the latter in the top 2 copper-producing countries in the world, Chile and Peru.

At the end of the day, friend-shoring will only make existing shortages of metals worse. By only accepting 20% of the most developed countries to trade with, 80% of the world as a source for raw materials, and as a manufacturing base, would be cut off. We are talking about a very small pool of metals supply to draw from.

Friend-shoring also rejects the comparative advantage rule that has been the basis of international trade for hundreds of years, worsening current supply chain bottlenecks because so few countries are involved, and accelerating already rampant inflation by raising the prices of imported goods. Also, dividing the world into trading blocks makes them prone to protectionism (again, higher prices,) and they could become hostile to one another, leading to military aggression and wars.

All in all, friend-shoring is a very bad idea, but it does have one silver lining for resource investors, and this is higher commodity prices. While metal prices have recently pulled back, on recession fears brought about by central bank interest rate hikes, arguably the supply shortages are very much intact (shown by low London Metal Exchange inventories), and the destruction of consumer demand will not come close to matching the higher demand for commodities from all the infrastructure programs being rolled out globally.

The tendency is for governments with lots of natural resources to guard them closely. Resource nationalism will limit the amount of new metal likely to come to market and climate change is already having an impact on mining, for example there is less water available for mineral processing in Chile, and Arctic mines are prone to flooding and subsidence due to melting permafrost. Friend-shoring is just one of many factors that will drive commodity prices higher, in the long-term.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.