Flying into a coffin corner – Richard Mills

2022.09.14

Gold is a commodity with limited supply, therefore it cannot be “created” by simply printing a piece of paper; it must be mined and processed into gold bars or coins. Therefore, gold’s value stays fairly stable over a long period of time, making it an ideal hedge against inflation, which makes fiat money “cheaper”.

And because gold carries no credit or counterparty risks, it is trustworthy in all economic environments, making it one of the most crucial reserve assets. An added appeal for gold is its inverse relationship with the US dollar, the world’s reserve currency; so long as the dollar is falling and gold is climbing.

Today, central banks hold more than 35,000 metric tons of the metal, which equates to about a fifth of all the gold ever mined. This is also the largest amount of gold maintained in global reserves since 1990.

The leading gold holders are some of the world’s most powerful nations, such as the US, Germany, Italy and France, all of which are keeping 60% of their foreign reserves as gold. This is a testament to the significance of gold in the central banking system.

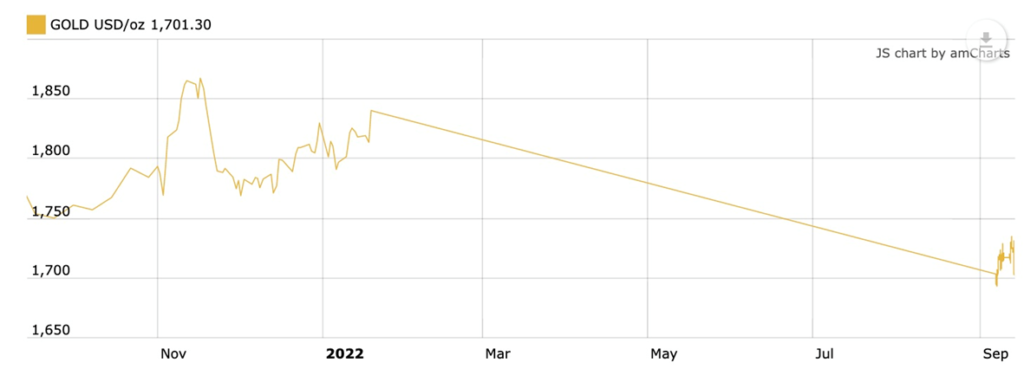

If gold is so great as an inflation hedge, why has the gold price languished in the face of inflation levels last seen 40 years ago?

The answer, of course, is the Fed. The US Federal Reserve started off declaring that historically high levels of inflation were “transitory”, and would go away with the resolution of covid-related supply chain bottlenecks. When inflation rocketed from 5.4% a year ago to 8.5% in March, then 9.1% in June, all the Fed’s talk of transitory inflation dissipated, and its strategy switched to fighting inflation through a series of aggressive interest rate hikes.

The Federal Reserve has raised interest rates four times this year, with the benchmark federal funds rate now set in a range of 2.25-2.50%, the highest since 2018. The central bank is targeting another 0.75% increase when its FOMC meets on Sept. 20-21.

It has certainly been disappointing to watch the gold price, and gold mining company valuations, crumble. Yet those who think that gold’s appeal has been permanently tarnished due to the Federal Reserve’s interest rate increases, should consider this:

Ultimately gold is a monetary metal that performs best during times of weak (weakening) economic growth and increasing money supply, as fiscal and monetary policy actors attempt to counter economic weakness through lowering the price of money and stimulating demand. This is what we witnessed from the end of March 2020 through late-2021.

Gold’s meteoric rise in 2020 corresponded with a major expansion of the money supply globally, as many central banks engaged in “quantitative easing” during the covid-19-induced recession. QE involves the purchase of government bonds by “printing money”. At the same time, central banks dropped their interest rates to near zero, to encourage borrowing and economic activity. Low interest rates and expansionary monetary policy are always good for gold.

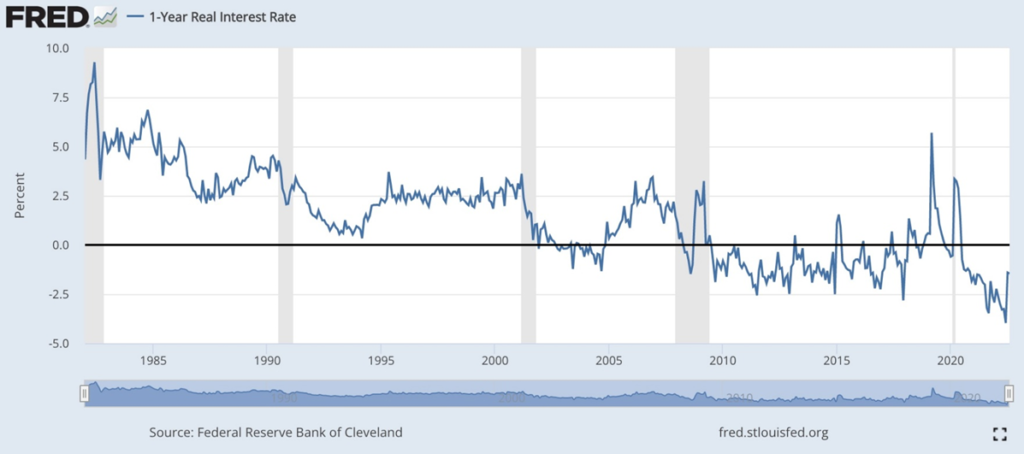

As for the current situation, it’s no surprise that rising interest rates have dented the gold price, since higher yields make income-generating assets like bonds a better option than gold, which offers neither a yield nor a dividend. Although, in most countries, the real interest rate (rate minus inflation) is still deeply negative, which for gold is a bullish price signal.

Inevitably the future gold price will turn on what happens with interest rates at the Federal Reserve, since the Fed controls monetary policy for the largest economy in the world and the biggest gold holder.

QE, revisited

Ever since the US dollar became the reserve currency in 1944, a decision made by the Bretton Woods delegation of 44 Allied countries, long-term US bonds, like the 30-year and the 10-year, have been held in high esteem by foreign governments, corporations and individuals.

Bondholders and the US government (through the Treasury) that issues them have a symbiotic relationship. Washington needs domestic and foreign entities to buy its debt, so that it can continue to run deficits, which keep getting added to the national debt, now at $30.8 trillion. Treasury buyers simply need the government to be able to pay them back their principal plus interest when the bond matures.

US government spending is basically a Ponzi scheme: politicians need to spend big to get re-elected, but they don’t have the money, so they borrow it (issue Treasuries) or they print it (they could raise taxes, but that is political suicide). Treasuries are considered a safe investment, so the government doesn’t worry about keeping on issuing them — like soap, diapers and gasoline, they will always find a willing buyer.

During the financial crisis the Treasury department came up with an innovative way to rescue the economy, by funneling hundreds of billions of dollars to US banks. The idea was the banks would receive the funds and make loans at rock-bottom (zero) interest rates, thus stimulating economic activity.

When a central bank uses this policy, known as quantitative easing, or QE, it buys large amounts of government and corporate bonds. This increases the amount of money circulating in the economy, which helps lower long-term interest rates. This in turn reduces the cost of borrowing, which spurs economic growth.

To a large extent, it worked. Despite some tense moments, the global economy was saved from falling into a depression, and eventually the stock market recovered. However, the cost was a humongous increase in the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, and the national debt.

From 2008, when the Fed balance sheet was just $1 trillion, four rounds of quantitative easing raised it to over $8 trillion.

The Treasury and the central bank were forced to adopt QE again in 2020, with the sudden onset of the coronavirus crisis. Money-printing resumed in earnest and interest rates were slashed to 0%. While the Fed’s balance sheet had been “wound down” (it sold bonds to get them off its balance sheet) to about $4 trillion in early 2020, according to Statista, between March 2020 and September 2022, QE more than doubled the balance sheet to $8.8T, as of Sept. 6.

Of course, the Federal Reserve wasn’t the only central bank to implement an expansionary monetary policy during the pandemic. The European Central Bank also began QE in March 2020. Statista reports the ECB since 2018 has steadily increased the M1 money supply in the euro area, to over 11.5 trillion euros, as of May 2022.

Meanwhile, the national debt has grown substantially under the watch of presidents Obama, Trump and Biden. When Trump was handed the keys to the White House in January 2017, the national debt stood at nearly $20 trillion. When he left, it was at $28.1T. Since the end of 2019, the debt has surged about $7 trillion, with over half of that consisting of money borrowed to pay for covid-19 relief programs.

Each interest rate rise means the federal government must spend more on interest. That increase is reflected in the annual budget deficit, which keeps getting added to the national debt, now standing at a gob-smacking $30.8 trillion. (usdebtclock.org)

Money-printing bonanza

Since the pandemic receded as a public health emergency, due mostly to widespread vaccination programs leading to “herd immunity”, the debt has faded from the headlines, replaced by concerns over deep, and seemingly intractable, inflation.

As mentioned earlier, the Federal Reserve has been steadily increasing interest rates to try and bring inflation, last measured at 8.3% in August, to heel. While there has been some success, for example US gasoline prices have fallen since hitting $5 a gallon earlier this summer, many areas outside of energy have seen sizeable increases. Food prices in August were 11.4% higher than a year earlier, the most since 1979, and electricity was 15.8% more expensive. Labor Department data on Tuesday showed the headline CPI rising 0.1% from July, for a 27th straight month of rising inflation. Core CPI, which strips out volatile food and energy prices, was dramatically hotter, rising 6.3% in August from a year earlier, up markedly from the 5.9% in June and July.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the average household is spending USD$460 per month more each month to buy the same basket of goods and services as last year.

Bloomberg reported that traders boosted bets that the Fed will raise interest rates by three-quarters of a percentage point, now seeing such an outcome as locked in.

Paradoxically, while central banks around the world try to defeat inflation by hiking interest rates, thereby crimping demand for goods & services, governments are adding to it with prodigious new spending. Remember, economies with fiat currencies rely on money-printing, and borrowing, to pay for their expenses.

The United States leads the way in this latest fiscal free-for-all, followed by Europe. The Biden administration’s $5.8 trillion federal budget will add nearly $15 trillion in new debt over the next decade, with annual budget deficits of at least a trillion per year.

According to a column in The Hill by Pennsylvania Republican Lloyd Smucker, Biden’s spending plan will further fuel inflation. For example, the administration’s ironically-titled ‘Inflation Reduction Act’ allocates more than $300 billion to energy and climate reform, alongside $64 billion to reduce health insurance costs. Put another way, the act means spending another trillion dollars on top of a deficit that is almost $1.5T, and a federal debt approaching $31T. Higher interest rates and Treasury bond yields will pile more interest on the debt, ballooning the deficit even further.

In Europe, an energy crisis fueled by natural gas restrictions owing to the war in Ukraine has hiked electricity costs to untenable levels.

At the start of August, British homeowners saw an 80% increase in their energy bills, following a record 54% spike in April. According to Global News, electricity costs for the average UK customer have risen from 1,971 pounds a year, about CAD$3,009, to 3,549 pounds, or $5,418. Britain has the highest inflation among the G7.

Incoming Prime Minister Liz Truss has reportedly drafted plans for a massive £130 billion support package over the next 18 months to help struggling households and businesses lower energy bills, according to policy documents seen by Bloomberg.

Germany, too, is taking action to provide electricity price relief for businesses and consumers. France 24 reports German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has just unveiled another €65 billion “inflation fighting” stimulus package. The quotation marks were added because, while the spending contains measures to help Germans prepare for the upcoming winter, including one-off payments to millions of pensioners and a plan to skim off energy firms’ windfall profits, it too will add to Germany’s 7.9% inflation rate in August. The latest agreement, states Zero Hedge, brings total relief to almost €100 billion since the start of the Ukraine war. The two previous relief packages included a tax cut on gasoline and a heavily subsidized public transportation ticket.

Sprott Money asks an interesting question: who’s going to fund the higher deficits caused by all of this new government spending? (and we’re not even counting the trillions in infrastructure spending planned by the US, the EU and China)?

The answer is the central banks. When governments go into debt to bail out their consumers who are being squeezed by inflation — and it’s not only higher prices for goods and services, but a shortage of labor, explained below, that is making things more expensive — the central banks will buy it, putting the developed economies on course for yet another round of quantitative easing.

Money-printing means more currency chasing fewer goods and services, ergo, higher inflation. QE also has a devaluing effect. As the dollar and the euro, for example, are worth less, it costs more to purchase the same basket of goods and services than before QE.

Tailwinds becoming headwinds

It may be perplexing to some, as to why inflation is such a problem, now. The answer goes far beyond the facile explanation provided by the media that it’s all about covid “supply chain issues”.

From the 1990s, the world economy enjoyed three decades of solid, low-inflation growth, helped by relatively benign “tailwinds” including stable geopolitics, technological advances, globalization and an ample pool of labor.

Yet instead of seizing the moment to make investments and reforms for the future, Reuters argues that governments took on debt to chase yet more growth.

This “growth at all costs” mentality blew back at developed-economy countries like the US, Canada and the UK, with the realization that globalization wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. While it made some people rich, millions more were worse off. The rise of populist politicians like Donald Trump and Europe’s far-right nationalists were among the consequences of globalization’s failure.

Reuters states, The 2008/09 financial crisis, pandemic and Ukraine war have revealed how fragile this growth fueled by cheap debt and just-in-time supply chains was. Now, the greater fear is that those tailwinds keeping it all up in the air are turning to headwinds.

“There is huge uncertainty as to how the economy will shape up now that the tectonic plates are shifting,” International Monetary Fund Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva told an event in Brussels this month, adding: “There will be pain”.

The shifting plates are making for a more expensive world. Thirty years of tailwinds are turning into headwinds. They include labor market changes as baby boomers and early Generation Xers retire; disruptions caused by extreme weather events and the cost of climate action, what I referred to in a recent article as “climate change mitigation”; volatile geopolitics (look at the war in Ukraine, the ever-simmering Middle East, China vs the US in the South China Sea, Taiwan, and North Korea, to name a few); and an uncertain world for trade.

Regarding the latter, China and the US remain locked in a trade war. Trump-era tariffs on Chinese imports are still in place, while a “West vs East” trade dynamic is emerging, centered around “de-dollarization” and the rise of competing currencies such as the yuan and the rouble.

Russia and China have both made moves to de-dollarize and set up new platforms for banking transactions outside of SWIFT that skirt US sanctions. The two nations share the same strategy of diversifying their foreign exchange reserves, encouraging more transactions in their own currencies, and reforming the global currency system through the IMF.

At the 14th BRICS summit in June, Russian President Vladimir Putin said “The issue of creating an international reserve currency based on a basket of currencies of our countries is being worked out.”

The issue of a shrinking labor pool is worth talking about further. According to the US Federal Reserve, half the drop in labor force participation since the pandemic is down to baby boomers retiring. By 2030 most boomers born between the end of World War II and 1964 will have hung up their shingle; in Europe old people will outnumber young people 2:1 by 2060; and in China, the proportion of over-65s has tripled since the ‘50s’.

The labor market is like any other market. Less people working (supply) and more job openings (demand) drives up the cost of labor. Workers are naturally demanding higher wages to meet the skyrocketing cost of living. The Globe and Mail reported that in Ontario, 650 collective agreements have been ratified by union members so far in 2022. The average annual wage increase in those settlements is 2.8%, compared to 1.2% in 2021 and 1.4% in 2020.

Regarding trade, we not only have tariffs on Chinese imports and vice versa (Chinese tariffs on US imports), but supply-chain disruptions, that are driving up inflation, too. A spokesperson for the IMF told Reuters that global supply snags due to the pandemic and now the Ukraine war have prompted companies in some cases to prioritise security of supply over lowest cost, a move that inevitably makes things pricier.

Moreover, governments are becoming more protectionist, as the benefits of globalization continue to ring hollow. Trade historian Douglas Irwin was quoted saying there is now a bi-partisan anti-trade reflex in U.S. politics and a genuinely pro-trade president has not sat in the White House since George W. Bush in 2009.

Tariffs, quotas and other trade barriers are usually done for political purposes; the higher per-unit cost of each targeted item is typically borne by consumers.

Climate change is also pushing us into a costlier world.

A 2020 study by the Insurance Bureau of Canada, cited by West Coast Environmental Law, calculates that local governments nation-wide need to spend $5.3 billion a year to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

As the Reuters story notes,

Doing nothing at all runs the risk of more frequent extreme weather causing outcomes such as resource shortages and lower labour productivity – both inflationary. A disorderly shift away from fossil fuels before other alternatives are in place would create energy shortfalls – and so also be inflationary.

(the latter is already happening. The energy crisis in Europe is partly driven by Russia restricting the supply of natural gas, but there has also been mal-investment, away from fossil fuels and towards more expensive renewables.)

The key point is this: with so many long-term, structural problems behind the current inflationary spiral (and it is spiraling) central bankers can’t fix inflation with quick hits to interest rates.

Higher costs related to changing demographics, more protectionist trade practices, and explosive climate change-related spending, all crimp the supply side of the economy, and there’s nothing the Fed can do about that.

To take just one item, consider: the cost to suppress wildfires has been rising steadily since 2018. The budget for wildfire suppression, within the Department of the Interior, is $1.53 billion in 2022, compared to $993 million in 2021 and $948M in 2018. Hurricane season is rapidly approaching, likely necessitating hundreds of billions more in federal funds, for hurricane relief. Where will the government find the money? Most likely they’ll print it, or borrow it.

Previously we reported on the rising costs of energy and food. Despite the recent lowering of gas prices and some grocery items, the problem of dual-track energy and food inflation is anything but solved.

Our global food supply, already in jeopardy due to the war in Ukraine, and drought conditions in many parts of the world, is set to become even more tenuous, as shortages of fuel and fertilizer in Europe look increasingly likely heading into the fall. Searing hot weather has caused widespread and highly unusual evaporation on some of Europe’s major rivers. Only half of France’s corn crop is in good or excellent condition, as the country experiences its worst dry spell on record. The European Union forecasts that corn yields this year could drop by nearly a fifth, adding to food inflation and boosting feed costs for farmers, who are already plagued with exceptionally high diesel and fertilizer prices.

The trading bloc says that compared with the average of the previous five years, harvests are down 16% for grain maize, 15% for soybeans and 12% for sunflowers.

Beyond Europe, a long hot summer has resulted in severe drought conditions in the United States, China and the Horn of Africa.

Other supply-related concerns, that are boosting the cost of living, were outlined by Charles Hugh Smith in his Of Two Minds blog (edited below for clarity and space). They include:

- Deglobalization is inflationary. Off-shoring production to low-cost countries imported deflation (product prices remained flat or declined) and boosted corporate profits. Deglobalization will increase costs and pressure profits. Reshoring essential supply chains will impose costs, pushing prices higher. Everything costs more in developed economies due to their high wages and social costs (pensions, healthcare, disability, etc.), high taxes, strict environmental standards and extensive regulations. Consumers will pay more as supply chains are on-shored.

- Energy will cost more. The price of oil and natural gas will fluctuate and could drop significantly as global demand drops, but in the long run the easy-to-access energy has been depleted and all energy will cost more.

- Capital will no longer have zero cost: interest rates may briefly return to near-zero but over time the cost of credit/ borrowing will rise. The 40+ year cycle of credit has bottomed and is reversing. As global risks rise, capital will demand a return.

- Definancialization will revalue assets. Interest rates fell for 40 years, rewarding borrowers and buyers of bonds, which increased in value with each click down in interest rates. These trends are reversing. Credit will cost more and every existing bond loses value with every click higher in interest rates/ yields.

- As profits from globalization dry up and credit costs rise, asset valuations based on cheap credit and rising profits will be repriced lower.

- The unprecedented inequality of income and wealth has changed perceptions and values, changing societies in ways few recognize. Young people with average jobs/ income have no hope of affording a home, retirement or raising a family. So they’ve given up.

- Non-essential jobs will be slashed. Finding people to clean hotel rooms is hard, and so resorts are cutting services even as they jack up prices. But enterprises can’t cut maids, drivers, waiters, welders, etc., nor can these jobs be automated, despite the robotic fantasies of the intelligentsia. Who they can cut are all the people spending their days in meetings.

- Deglobalization will re-order mercantilist economies that have depended on exports for their bread and butter and consumer economies dependent on essentials imported from elsewhere. Essentials (food, energy, technology) will increasingly be viewed (correctly) as national security priorities. Relying on other nations for essentials will be viewed (correctly) as increasing vulnerability and risk.

- All of these are structural dynamics that won’t go away in a few months or years.

Conclusion

The US Federal Reserve has shown repeatedly it is incapable, or unwilling, to base its decisions on the myriad factors that go into an economy, beyond its narrow two-pronged focus of manipulating interest rates and maintaining full employment.

Former Fed Chair Paul Volcker is widely credited with curbing inflation, but in doing so, he is also criticized for causing the 1980-82 recession. The way he did it was the same as the current US Federal Reserve is doing: raising the federal funds rate. From an average 11.2% in 1979, Volcker and his board of governors through a series of rate hikes increased the FFR to 20% in June 1981. This led to a rise in the prime rate to 21.5%, which was the tipping point for the recession to follow.

A more recent example of what happened when a hostile Fed tried a significant interest rate hike, was in 2018. To wean the economy off of ultra-low interest rates, in 2015 the Fed increased them a quarter-percent, from 0.25 to 0.5%. In a series of subsequent raises, the Fed tightened from 0.5% in December 2015 to 2.5% in December 2018.

We all remember what happened to the economy. For three months the stock market plunged nearly 20%, before Powell relented, and began loosening again.

As for the current situation, the record needle appears to be stuck and the same song is playing, over and over. On Tuesday, Sept. 13, following the release of August’s inflation data, North American stock markets plunged, on the assumption that the Fed will raise interest rates yet again when it meets next week, on account of higher inflation.

CBC News reports it was the worst day for the S&P 500 since the early days of the pandemic in 2020. The Dow Jones Industrial Average closed down 1,276 points and the broader S&P 500 lost nearly 177 — a drop of roughly 4% each. The technology-focused Nasdaq was off by more than 600 points, or >5%.

Clearly the markets have an intense dislike for Powell’s plan to keep raising interest rates to stifle inflation, notwithstanding all the negative consequences to the broader economy this entails.

I like Reuters’ analogy of what in aviation they call a “coffin corner” — this is the delicate spot when an aircraft slows to below its stall speed and can’t generate enough lift to maintain its altitude. It takes a skilled pilot “to get the aircraft back to a stable, safer place”. Personally, and I don’t think I’m alone in this view, I don’t have much confidence in the pilots that are flying the Fed aircraft, to avoid the coffin corner.

The Brooking Institution recently presented data that casts doubt on whether the economy can get through this bout of inflation without a large increase in the unemployment rate. The paper says the Fed would have to allow unemployment to rise as high as 7.5%, an outcome that would “pay” for inflation at a cost of 6 million jobs.

6 million jobs! I can’t think of a scenario whereby any politician or central banker would entertain such a cataclysmic hit to the economy. Close to 10 million US workers were sidelined due to the pandemic (Pew Research), so we are talking another 6 in 10 workers would have to be let go. Ain’t gonna happen, folks.

Instead, the Fed and other central banks will continue to raise interest rates to fight inflation, but without realizing it, they’re flying into a coffin corner. Take the stock market plunge we saw today, Sept. 13. Just the spectre of another interest rate hike — the actual raise comes next week — had investors/ traders hitting the panic button. It was the worst day on Wall Street since the start of the pandemic. Imagine the Fed as pilots in an Airbus A380-800. They’re trying to get this massive plane to lift off but they’re pulling too hard on the stick (raising interest rates) and the engines (the stock markets) are failing. Now the plane and all its passengers (investors) are facing certain death if this airliner, the largest in the world, can’t pull out of a death spiral and it plummets to the ground, killing all on board.

Janet Yellen, the current US Treasury Secretary, and the former Fed chair, recently said for the Federal Reserve to achieve a “soft landing” for the US economy, it will need “great skill and luck.” No kidding.

Continuing with the plane crash analogy, as the engines scream and the plane loses altitude, the oxygen masks drop down. This is gold. Investors are looking for a way to survive the crash, and they, imo, will find it in bullion.

While the US dollar will likely continue to rise against the sliding euro and the yen, amid market uncertainty, its days are numbered.

The US dollar is the most important unit of account for international trade, the main medium of exchange for settling international transactions, and the store of value for central banks.

Lately though, “de-dollarization” is being pursued by countries with agendas at odds with the US, including Russia, China, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Since 2018, the Bank of Russia has substantially reduced the share of dollars in its foreign exchange reserves, through purchases of gold, euros and yuan. As of March, 2022, Russia was the fourth largest holder of gold bullion, behind the US at no. 1, Germany, Italy and France. The country’s gold holdings have tripled since the first Russo-Ukraine war in 2014, and are estimated at around 20% of the BoR’s total reserves.

China and Russia have drastically reduced dollar usage in conducting trade. In 2015 about 90% of transactions used the dollar. After the trade war between the US and China broke out, the figure by 2019 had dropped to 51%. And that was before the war in Ukraine.

Russia has proposed a gold and commodities-backed rouble, as well as its own international standard of precious metals exchange dubbed the Moscow World Standard.

Fiscal spending by governments must be funded by issuing more debt, and the only institutions that can buy that debt are central banks. As Sprott Money argues,

They will also need to cap yields on the bonds to avoid insolvency. See Japan. Meanwhile, currencies are devalued daily, some faster than others, and inflation roars higher. Capped yields and higher inflation mean lower real yields are coming. When that happens, Gold and Silver will benefit handsomely.

Sprott Money also notes that China continues to load up on gold, while dumping US Treasuries, which have dropped below $1 trillion to a 12-year low. Why is China selling Treasuries and buying gold? Well, probably because they saw what happened to Russia’s dollars. Plus the fact that they are losing confidence in the US dollar, as the national debt approaches $31 trillion and US influence abroad wanes.

De-dollarization is likely to accelerate and the best alternative is gold, which despite offering neither a dividend nor a yield, is the traditional and most trusted safe haven when it comes to protecting your assets against inflation and currency depreciation.

The central banks are going to try to keep fighting inflation through tightening monetary policy (increasing interest rates), but they don’t recognize, or don’t care, that there is a tectonic shift going on, that is flipping all we have known for 30 years on its head. It’s the on-shoring and friend-shoring that we wrote about, the deglobalization, the shortage of labor, goods and raw materials. There’s also unstable geopolitics, the rising costs of climate change, increasing trade protectionism, and last but certainly not least, the incessant money-printing. All of the above is inflationary, it’s all structural, and none of it is fixable with a quick bump to interest rates.

Central banks can’t print or buy their way out of this this inflation, and the quicker they realize this and back off, the better off we’ll be. In the meantime, investors imo should take a close look at gold and silver as a safe place to park their money during these turbulent times.

From the start of pandemic-related government spending in the spring of 2020, to today, the US government has printed over $6 trillion. During that period, the US money supply increased by 41%, with the Fed’s actions amounting to the biggest monetary explosion that has occurred in the 227 years since the founding of the United States. Read more

Is the Fed really going to keep raising interest rates like the Volcker Fed did in 1981, until it crashes the economy and causes a recession? At AOTH, we believe the Fed will soon pause its rate hikes, when it realizes that the hikes are doing more harm than good, and that “getting to 2%” inflation is completely unrealistic.

When it pivots to lowering interest rates, and other central banks follow suit, we expect gold and silver prices to turn sharply higher.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.