Fire and Ice

2021.08.13

A prolonged stretch of hot weather in southern British Columbia has seen tinder-dry forests burning for over a month. Out-of-control wildfires, evacuation orders, and dangerous to breathe smoke that blankets communities for weeks, are now annual events in the BC Interior.

On June 29, Canada’s highest-ever recorded temperature, 49.6 C, was reached in Lytton, BC. The day after, the village of 250 inhabitants was destroyed by fire — buildings razed to their foundations and the hulking wrecks of cars left smoldering.

The “heat dome” that covered much of western North America at the end of June, shattering temperature records, isn’t the only weather event making headlines. Forest fires caused by extreme heat and drought are releasing record carbon emissions from Siberian forests and driving Greeks to flee their homes by ferry.

The monstrous wildfires happening in the United States are the latest consequence of a 21-year drought in the southwestern US (and into the northern states including Oregon), as depicted in the latest map by US Drought Monitor. Red areas are extreme drought, brown areas show exceptional drought. The current dry stretch started in 2000 and hasn’t let up, putting it second only to a highly arid period in the last 1500s.

An estimated 579,614 acres of forest has been burnt in California, plus 400 structures destroyed (remarkably, there are yet no deaths). The nation’s largest wildfire, the Bootleg fire in southern Oregon, is currently at 413,765 acres, though luckily after burning for over a month it is 98% contained.

There have also been unprecedented rains followed by catastrophic flooding in China and Europe, and a flash frost in Brazil that killed most of the young coffee plants.

Earlier this week, tourists waded through ankle-deep water in Venice’s St. Mark’s Square.

In Barrie, Ontario, a tornado designated as EF-2 (wind speeds up to 217 km/h) slammed into a residential neighborhood destroying homes and injuring 11 people. The twister, not normally seen that far north, was one of five recorded in southern Ontario in June.

We don’t have to wait years for the worst impacts of climate change to occur. They’re already here.

A report this week by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says global warming is on the verge of becoming out of control (if it isn’t already), and warns that the world is certain to face further climate disruptions for decades if not centuries to come.

Drawing on more than 14,000 scientific studies, it gives the most complete picture yet of how climate change is altering the natural world and what could lie ahead.

In language couched stronger than previous IPCC reports, which have become standard and easy to ignore, much like the boy who cried wolf, the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) says that unless rapid and large-scale action is taken to reduce carbon emissions, the average global temperature is set to cross the 1.5 degree Celsius warming threshold within 20 years. That, my friends, is within most of our life times.

A rise of 1.5 C is considered to be the tipping point, beyond which further warming is expected to have disastrous economic, political and environmental consequences.

The report says emissions have already pushed the global temperature up by an average 1.1 degrees beyond the pre-industrial average, and that pledges to cut emissions are nowhere near enough to start reducing the level of greenhouse gases that have accumulated in the atmosphere.

Reuters teases out a few more key points from the 60-page report, including:

- The deadly heat waves, gargantuan hurricanes and other weather extremes that are already happening will only become more severe.

- The 1.1C warming already recorded has been enough to unleash disastrous weather. Further warming could mean that in some places, people could die just from going outside. [569 people died as a result of the extreme heat wave that hit southern BC at the end of June. Most were seniors living in apartments without a/c – Rick]

- Some changes are already “locked in”. Greenland’s sheet of land-ice is “virtually certain” to continue melting, and raising the sea level, which will continue to rise for centuries to come as the oceans warm and expand.

- But even to slow climate change, the report says, the world is running out of time. If emissions are slashed in the next decade, average temperatures could still be up 1.5C by 2040 and possibly 1.6C by 2060 before stabilising.

- And if, instead the world continues on its the current trajectory, the rise could be 2.0C by 2060 and 2.7C by the century’s end. The Earth has not been that warm since the Pliocene Epoch roughly 3 million years ago – when humanity’s first ancestors were appearing, and the oceans were 25 metres (82 feet) higher than they are today.

- It could get even worse, if warming triggers feedback loops that release even more climate-warming carbon emissions — such as the melting of Arctic permafrost or the dieback of global forests. Under these high-emissions scenarios, Earth could broil at temperatures 4.4C above the preindustrial average by the last two decades of this century.

To the report itself, more granular climate data is revealed, showing the extent of global warming in its various manifestations. An edited summary of the main points follows:

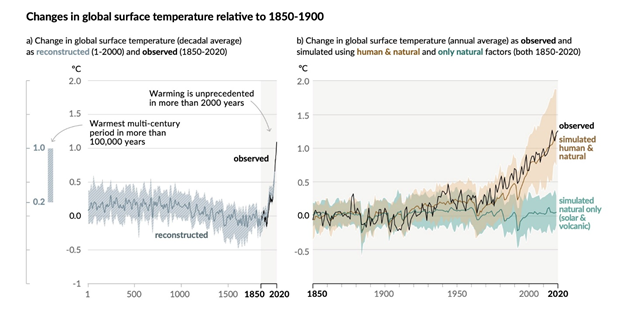

- The scale of recent changes across the climate system as a whole and the present state of many aspects of the climate system are unprecedented over many centuries to many thousands of years.

Warming

- It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred.

- Each of the last four decades has been successively warmer than any decade that preceded it since 1850. Global surface temperature was 1.09°C higher in 2011-2020 than 1850-1900, with larger increases over land (1.59 °C) than over the ocean (0.88°C).

- Global surface temperature has increased faster since 1970 than in any other 50-year period over at least the last 2,000 years. Temperatures during the most recent decade (2011-2020) exceed those of the most recent multi-century warm period, around 6,500 years ago (0.2°C to 1°C relative to 1850-1900). Prior to that, the next most recent warm period was about 125,000 years ago.

- It is virtually certain that heat waves have become more frequent and more intense across most land regions since the 1950s, while cold waves have become less frequent and less severe. Marine heat waves have approximately doubled in frequency since the 1980s.

- Changes in the land biosphere since 1970 are consistent with global warming: climate zones have shifted poleward in both hemispheres, and the growing season has on average lengthened by up to two days per decade since the 1950s in the northern hemisphere.

- Climate change has contributed to increases in agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions due to increased land evapotranspiration.

Emissions

- Since 2011 (measurements reported in AR5), greenhouse gas concentrations have continued to increase in the atmosphere, reaching annual averages of 410 ppm for carbon dioxide (CO2).

- In 2019, atmospheric CO2 concentrations were higher than at any time in at least 2 million years and concentrations of methane and nitrous oxide were higher than at any time in at least 800,000 years.

- It is likely that well-mixed GHGs contributed a warming of 1.0°C to 2.0°C. It is very likely that well-mixed GHGs were the main driver of tropospheric warming since 1979.

Storms

- Global average precipitation over land has likely increased since 1950, with a faster rate of increase since the 1980s.

- Mid-latitude storm tracks have likely shifted poleward in both hemispheres since the 1980s, with marked seasonality in trends (medium confidence).

- The frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have increased since the 1950s over most land area.

- It is likely that the global proportion of major (Category 3–5) tropical cyclone occurrence has increased over the last four decades, and the latitude where tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific reach their peak intensity has shifted northward.

- There has been an increase in the chance of compound extreme events since the 1950s. This includes increases in the frequency of concurrent heatwaves and droughts on the global scale; fires in some regions of all inhabited continents; and compound flooding in some locations.

Glaciers & Arctic sea ice

- There has been a global retreat of glaciers since the 1990s and a decrease in Arctic sea ice between 1979-1988 and 2010-2019 (about 40% in September and about 10% in March).

- The global nature of glacier retreat, with almost all of the world’s glaciers retreating synchronously, since the 1950s is unprecedented in at least the last 2,000 years.

- There has been a decrease in northern hemisphere spring snow cover since 1950, and surface melting of the Greenland ice sheet over the past two decades.

- In 2011-2020, annual average Arctic sea ice reached its lowest level since at least 1850. Late summer Arctic sea ice area was smaller than at any time in at least the past 1,000 years.

Sea level rise & ocean warming

- Global mean sea level increased by 0.20m between 1901 and 2018. The average rate of sea level rise was 1.3mm between 1901 and 1971, increasing to 1.9mm between 1971 and 2006, and further increasing to 3.7mm between 2006 and 2018.

- Global mean sea level has risen faster since 1900 than over any preceding century in at least the last 3,000 years.

- The global ocean has warmed faster over the past century than since the end of the last deglacial transition (around 11,000 years ago).

- The global upper ocean (0-700m) has warmed since the 1970s. CO2 emissions are the main driver of current global acidification of the surface open ocean. Oxygen levels have dropped in many upper ocean regions since the mid-20th century.

- A long-term increase in surface open ocean pH occurred over the past 50 million and surface open ocean pH as low as recent decades is unusual in the last 2 million years.

Collapsing polar vortex, wandering jet stream

We understand that climate change causes odd weather patterns, due to the wandering jet stream.

Because the Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the planet, the jet stream is thrown off course, with increasing frequency of meandering pockets of air, which create stormy weather.

The polar vortex is a seasonal atmospheric phenomenon whereby high winds swirl around an extremely cold pocket of Arctic or Antarctic air. The winds are like a barrier that contains the cold air, but when the vortex weakens, the cold air “escapes” from the vortex and travels south, bringing with it a cold blast of Arctic weather.

The scientific evidence suggests the same phenomenon is responsible for heat waves.

A recent example is the “heat dome” that settled above western North America in June. CBC News describes a heat dome as essentially a mountain of warm air built into a very wavy jet stream, with extreme undulations. When the jet stream — a band of strong wind in the upper levels of the atmosphere — becomes very wavy and elongated, pressure systems can pinch off and become stalled or stuck in places they typically would not be.

The bigger question is, what does the wandering jet stream mean, and should we be concerned, even if we’re not affected by unseasonably strange, bad weather?

The short answer is yes, because it shows the consequences of climate change are coming sooner than we think. It all starts with warming poles, and melting Arctic ice.

A recent scientific report found that Canada is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. Even worse is what’s happening in the Arctic, where the temperature has risen 2.3 degrees C compared to 70 years ago. Add another degree of warming during winter, states the report from Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Greenland has been seeing many more hours than normal of above-freezing temperatures. In June 2019, 40% of the large northern landmass was melting, causing a loss of 2 billion tons of ice in a single day. That sounds bad, but it was actually worse in 2012, when the entire Greenland ice sheet saw melting, the first time that has happened in recorded history.

As ice melts during the summer, the Arctic Ocean warms. That heat gets radiated back to the atmosphere in winter, which reduces the intensity of the northern polar vortex winds. The polar vortex gets disrupted, allowing cold air in the center of the swirling cyclone above the pole to migrate south, resulting in meteorological aberrations like snowfalls in Florida.

While occasional breakdowns of the polar vortex are nothing to be concerned about, they are becoming more common. A study in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society found that a weakening polar vortex has become more common during the past four decades, and that a weaker polar vortex, brought on by a melting Arctic, explained 60% of the cooling in Eurasia since 1990.

The scary part of all this is the spectre of the polar vortex collapsing. This would mean a total disruption of normal atmospheric warming and cooling. Without halos of swirling Arctic and Antarctic winds serving to cool the poles, they would be left to heat up, accelerating global warming.

So far in this article, everything we’ve written is based upon a gradual warming scenario, albeit happening at a faster clip than expected. The fable of the boiling frog seems appropriate. If a frog is suddenly put into a pot of boiling water, it will jump out. But if the frog is put into tepid water, it won’t perceive the danger and will be cooked to death. Like a society of frogs, we perceive the danger of climate change, but we are content to marinate in the warm bubbles, unconcerned about how hot it’s getting to do anything about lowering the temperature.

But the really frightening scenario is not our climate changing slowly, almost imperceptibly, but a sudden lurch forward, like shifting a sports car into high gear.

The North Atlantic Current

Crucial to an understanding of global warming are the changes to the North Atlantic Current, a vast movement of water that extends the Gulf Stream north-east, starting around the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. The current flows east before sharply veering north, transporting warm tropical waters from the Gulf Stream like a giant conveyor belt to northern latitudes and eventually the Arctic Ocean. The current bounces off Greenland and Iceland, then heads back south, carrying cold water with it.

In places where the warm, salty water near the surface meets cold, less salty water at depths, the water is pushed down in huge, rotating columns called chimneys, some of which churn almost to the bottom of the ocean, 2.5 km from surface.

Little is known about these mysterious structures except that there are less of them, and that their reduction corresponds with loss of ice (a survey done in 2004 found two chimneys in the Greenland Sea, whereas previous surveys found many more chimneys).

Meanwhile another current, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), exchanges warm water from the equator with cold water from the Arctic, transporting warm and cold water to the North and South Poles.

Watch the circulation of the currents in this video

Without climatic disruptions, the currents work to move water around the globe, along with nutrients key to the survival of marine species. The Gulf Stream, one of four currents known as the North Atlantic Gyre, even played a role in the exploration of the New World, with European explorers catching the winds in their sails from the Gulf Stream as they searched for new lands.

However in recent times climate scientists have been raising concerns that rising temperatures could throw a wrench into the conveyor-like currents system. Sensors stationed along the North Atlantic show that the volume of water moving northward has been sluggish, potentially affecting sea levels and weather.

But the more disruptive scenario involves the AMOC. Scientific American states:

As global temperatures rise with the levels of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, the AMOC could be disrupted by an influx of freshwater from increasing precipitation in the North Atlantic and the melting of sea ice and glaciers on land. The added freshwater lowers the water density in the zone where deep water forms, backing up and weakening the overall flow of the AMOC like a clogged sink. That slowdown means less heat is transported northward, leading to cooler ocean temperatures in a region below Greenland, and warmer temperatures off the US east coast. That warming leads to higher sea levels along the coast and raises sea temperatures where economically valuable cold-loving species like cod and lobster live.

The slowing of the AMOC could also mean colder winters across the eastern US, and increases the likelihood of summer heat waves across Europe. Two recent studies show that the amount of water surging through the AMOC has slowed to a 1,600-year low.

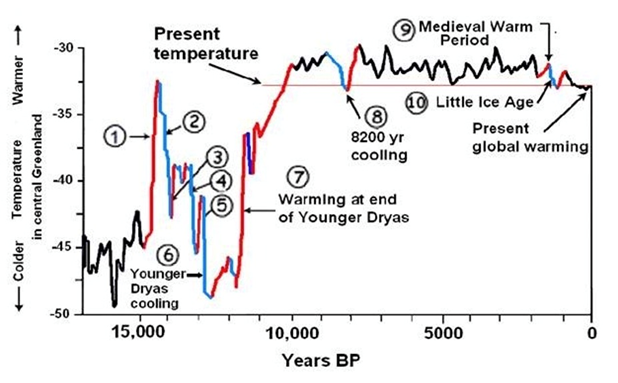

The Younger Dryas

The prevailing theory of what caused an abrupt freezing 20,000 years ago involves a large influx of fresh water from a very large lake, called Lake Agassiz (now the Great Lakes), into the Atlantic Ocean likely via the St. Lawrence Seaway, which stopped the North Atlantic Current in its tracks, plunging Europe and much of the northern hemisphere into interminable winter.

Another intriguing theory that supplements the Younger Dryas explanation of the sudden onset of an ice age involves a comet striking the earth. The website Science details the story of a geologist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, who gathered proof of a 31-kilometer wide impact crater under a kilometer-thick sheet of ice known as the Hiawatha Glacier, in Greenland. Some researchers on his discovery team believe the massive impact on the ice sheet would have sent meltwater surging into the Atlantic Ocean, thereby disrupting the conveyor belt of ocean currents — just as the spilling of the contents of Lake Agassiz did.

The Younger Dryas refers to an interruption in the heating of the climate that occurred after the last global ice age that started receding about 20,000 years ago.

Within decades temperatures dropped 2 to 6 degrees C, causing the advance of glaciers and dry conditions. The mini-ice age is thought to have lasted between 1,000 and 1,300 years, and like it started, also ended abruptly, within 40 to 50 years.

Could it happen again? An alarming news story last week strongly suggests it could. Reuters reports on a study by the Potstdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, published in the journal ‘Nature Climate Change’, wherein climate models show that the AMOC is at its weakest in a thousand years.

We already know from three paragraphs above that the current is at a 1,600-year low, so what’s new here? The study’s author says it’s not only the strength of the current that is at risk but its stability.

“The loss of dynamical stability would imply that the AMOC has approached its critical threshold, beyond which a substantial and in practice likely irreversible transition to the weak mode could occur,” said Niklas Boers.

“The findings support the assessment that the AMOC decline is not just a fluctuation or a linear response to increasing temperatures but likely means the approaching of a critical threshold beyond which the circulation system could collapse.”

Yes. The very same scenario envisioned by the movie ‘The Day After Tomorrow’. Truth being stranger than fiction, Reuters warns that A potential collapse of the system could have severe consequences for the world’s weather systems.

If the AMOC collapsed, it would increase cooling of the Northern Hemisphere, sea level rise in the Atlantic, an overall fall in precipitation over Europe and North America and a shift in monsoons in South America and Africa, Britain’s Met Office said.

Other climate models have said the AMOC will weaken over the coming century but that a collapse before 2100 is unlikely.

Well that’s a relief. But how can they be sure? The mini-ice age that resulted from the emptying out of Lake Agassiz, a huge inland waterbody in North America, started and ended quickly, each within four to five decades, a blink of an eye in Earth science terms.

Applying the Younger Dryas theory to current global warming, and all the evidence we have of it, including melting sea ice, glaciers and permafrost, rising sea levels, disruptions to the polar vortex, freak storms, heat waves, forest fires, etc., it’s interesting to speculate what could happen.

We know that during the Younger Dryas, a long period of global warming after the last major ice age suddenly ended and resulted in “global cooling”. Is that what’s in store for planet Earth, if we compare our current warming trend? If so, Europe and North America’s east coast won’t be so worried about heat waves, but instead, could be looking at a frozen landscape more resembling ‘A Game of Thrones’.

Then again, the climatic conditions of today are totally different from 12,000 years ago. How will the depletion of Arctic sea ice, warming oceans, collapsing polar vortices and wandering jet streams, when tossed into the equation of a warming planet, affect our future climate? It’s hard to say, and difficult to predict, which areas will be most and least affected by climate change. We truly are moving into uncharted territory.

Prepping for change

For many people uncertainty brings anxiety. Climate change may not be top of mind for the majority, who are preoccupied with the more immediate issues of putting food on the table, getting children up every morning and off to school, looking after elders, etc., but there is one thing for certain: it affects everyone.

One way to confront the unknowns of a warming planet, and thereby reduce worry around it, is to prepare. Recent events particularly in the United States are providing fuel for a growing movement of “preppers” who are waking up to the worsening reality of supply chain interruptions and food shortages.

Covid is a good example. At the beginning of the pandemic, shoppers rushed into supermarkets, grabbing what they considered to be the most important grocery items for riding out a crisis, including toilet paper, pasta and meat. The sight of empty shelves shocked many people into planning for what they would do in the event of a natural disaster like an earthquake. A power grid failure in Texas this past February, when millions of homes were plunged into darkness during a freak winter storm, is another example that got Americans thinking about “armageddon-type” scenarios.

These folks aren’t your regular survivalists living in a log cabin and running around the back 40 with a loaded shotgun. Travis Maddox, a Missouri man who in 2009 launched his own Youtube channel, ‘The Prepared Homestead’, tells The Epoch Times an increasing number of people are sending him really personal emails. They’re not crazy extremists. These are single moms, elderly people, disabled people, regular working people. They’re realizing that things are changing. They can just feel things are changing rapidly,” he said…

In the last year alone, roughly 45 percent of Americans, or about 116 million people, said they spent money preparing for hard times or spent money stockpiling survival goods, according to Finder.com.

As a former Boy Scout, I like the idea of being prepared. It’s about time we realize that the old order, a time of ubiquitous consumption, of globalization involving unfettered and conflict-free trade, of long uninterrupted supply lines, is over.

Covid was a warning, a shot heard loud and clear that we are entering a different, far more uncertain period. Covid-19 is very unlikely to be the last pandemic. With a global population approaching 10 billion, the opportunities for strange and new viruses to grow and mutate are only going to increase.

The storming of the US Capitol in January, and the Black Lives Matter protests, are a reminder of the political and social tensions hiding under the veneer of American democracy.

In an uncertain future, we need to live more “local”, we need to be more self-reliant. Above all, if we’ve learned nothing else from covid, we need to shorten our supply chains. Stop buying strawberries from Peru in February and start canning local fruit and vegetables in summer for storage the following winter.

Being a prepper doesn’t have to mean constructing a bunker and filling it floor to ceiling with canned food. We can simply live more like our ancestors. “Prepping is something most people did all the time” in bygone years. “Our grandparents were preppers,” Maddox says in The Epoch Times story.

Back to climate change, I just can’t imagine if the Earth keeps warming as we know it will continue to do, according to its natural cycles, how bad things could get. I see a world where cities no longer function properly — with coastal cities either drowned or inundated with frequent flooding from storms made worse by rising sea levels, and freshwater aquifers polluted by saltwater intrusion. I see more people moving inland, seeking a simpler, safer rural life.

Places that seem fine now will become uninhabitable. There will be cities that simply become too hot for human survival. More people will be on the move, like the BC wildfire evacuees we see now. Higher temperatures will mean more extreme heat, droughts and forest fires.

However, we can’t underestimate the power of human ingenuity and the impulse to survive. We will make it, we just need to be smarter about where we choose to live, and how we live. There is still time to think about, and plan for the future.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.