Fast-shrinking Arctic sea ice means more extreme weather patterns – Richard Mills

2023.04.11

Sometimes it takes an April ice storm in Canada to really be reminded of the impacts of global warming.

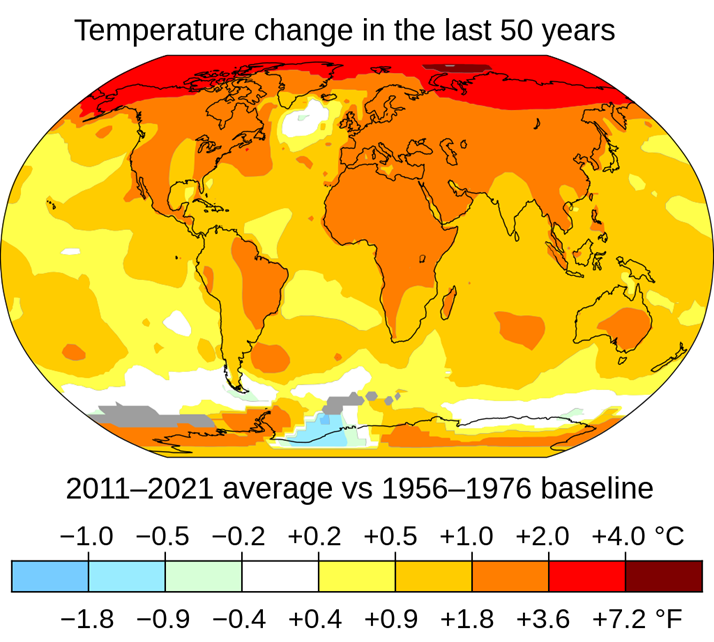

Scientists have found that the Arctic — the “frontline of climate change” — is heating up four times faster than the rest of the world. Much of this has to do with the phenomenon known as “Arctic amplification”, or the loss of sea ice.

Shrinking Arctic Ice Cover

The Arctic Ocean is mostly covered with a layer of sparkling sea ice. But as the planet warms, the sea ice begins to dissipate and exposes more of the ocean surface, allowing heat to escape from the warmer water into the colder atmosphere. And as more ice vanishes from the sea, Arctic temperatures rise faster and faster, which in turn makes the sea ice vulnerable to further melting.

Provisional data from the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC) shows that this year’s Arctic sea ice winter peak has reached its fifth lowest on record.

The extent of Arctic sea ice changes throughout the year – growing during the winter before reaching its peak for the year in February or March, and then melting throughout the spring and summer towards its annual minimum, typically around September.

Using satellite data, scientists can track the growth and melt of sea ice, allowing them to determine the size of the ice sheet’s winter maximum extent as a way to monitor the “health” of the Arctic.

According to NSIDC’s latest satellite recording, this year’s Arctic maximum extent of 14.62 million square kilometers is 1.03 million below the 1981-2010 average maximum extent – ranking as the fifth lowest since record-keeping started. This reduction, according to the NSIDC, is equivalent to an area larger than Egypt.

And since satellite records began in 1979, the average ice extent for the entire month of March has shrunk by an average of 38,850 square kilometers a year, representing a total loss of 2.28 million square kilometers — an area bigger than Greenland.

The lowest peak coverage occurred in 2017, when the ice extended over just 14.4 million square kilometers before beginning to shrink. According to NSIDC recordings, five of the lowest maximum extents have occurred since that year, and the 10 lowest coverage years have all taken place since 2006.

“For several months this year, global sea ice extent – Arctic plus Antarctic – has been at a record low,” Dr. Mark Serreze, director of the NSIDC, told Carbon Brief.

According to Serreze, the greatest amount of Arctic warming seems to be taking place on the Atlantic Ocean side of the Arctic Ocean near the Barents Sea.

“While the causes are still being studied, it appears that warm water from the Atlantic is playing a bigger role in ice melt, on top of the impact from a warming atmosphere,” Serreze said in a Bloomberg interview, citing the change in ocean circulation as one of the main causes.

He also noted that this year’s reversal from net freeze to net melt took place about six days earlier than the average from 1981 to 2012, but factors like wind can cause a fair amount of variability.

This Arctic maximum is “another data point adding to our understanding of a dramatically changing place,” comments Dr. Zack Labe, a researcher working at NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and the Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Program at Princeton University.

These effects are clearly linked to human-caused climate change and have major implications regionally across the Arctic,” Labe adds.

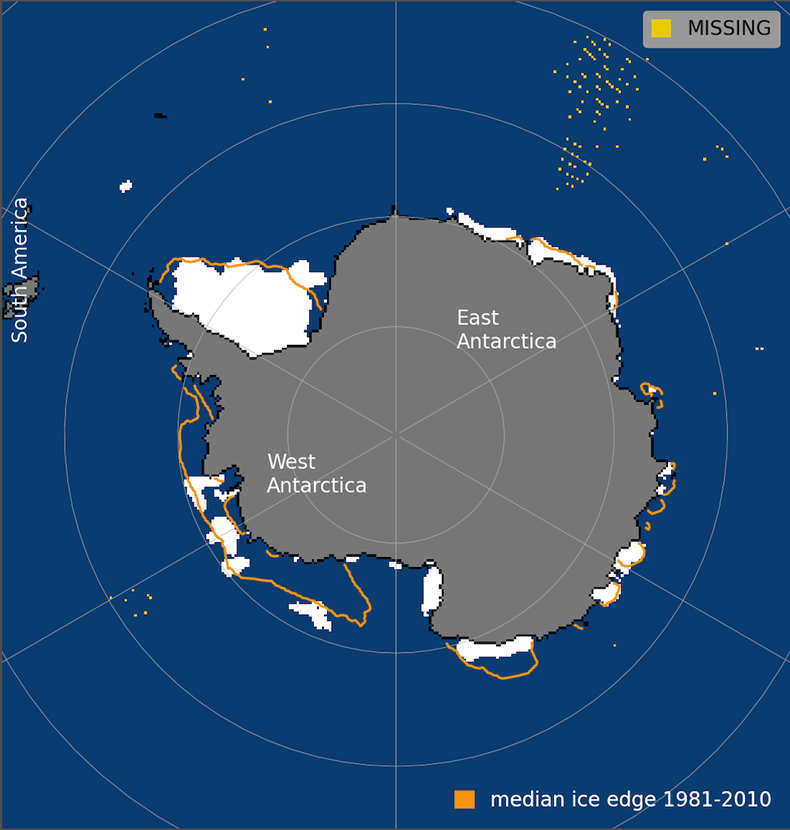

Antarctic Melting

The alarm bells are also being rung from the other side of the globe, where the South Pole, similar to its northern counterpart, is warming faster than the global average at three times the pace.

The Antarctic Peninsula has had an intense melt season with above-average melting persisting through much of February, according to NSIDC satellite data, as relatively warm conditions were present in many parts of the ice sheet.

Saturated snow from a high melt year and low sea ice in Bellingshausen Sea have led to a series of minor calving events on the Wilkins Ice Shelf. Elsewhere in Antarctica, melting was near average.

Recent study revealed that Antarctic sea ice has hit its lowest levels ever recorded. In the southern hemisphere summer of 2022, the amount of sea ice dropped to below 2 million square kilometers for the first time since satellite tracking began. Fast-forward a year later, a new record of 1.79 million square kilometers was set, representing the third time this record has been broken in six years.

Data from NSIDC shows that the Antarctic sea ice extent averaged a record low 3.23 million square kilometers during January 2023, shattering the previous January record low of 3.78 million in 2017.

In the southern hemisphere’s spring, strong winds over western Antarctica buffeted the ice, Dr. Will Hobbs, an Antarctic sea ice expert at the University of Tasmania told The Guardian. At the same time, large areas in the west of the continent had barely recovered from the previous year’s losses.

“Because sea ice is so reflective, it’s hard to melt from sunlight. But if you get open water behind it, that can melt the ice from underneath,” says Hobbs.

While melting sea ice does not directly raise sea levels because it is already floating on water, scientists believe they will still cause knock-on effects that destabilize the massive ice sheets and glaciers behind them on the land.

One major area of concern is a marked loss of ice around the Amundsen and Bellinghausen seas on the continent’s west. Even as the average amount of sea ice around the continent grew up to 2014, these two neighboring seas saw losses, satellite data shows.

That’s important because the region is home to the vulnerable Thwaites glacier — known as the “doomsday glacier” because it holds enough water to raise sea levels by half a meter.

“We don’t want to lose sea ice where there are these vulnerable ice shelves and, behind them, the ice sheets,” Matt England, an oceanographer and climate scientist at the University of New South Wales, says.

Data provided by Dr. Rob Massom, of the Australian Antarctic Division, and Dr. Phil Reid, of the Bureau of Meteorology, shows that two-thirds of the continent’s coastline was exposed to open water during February – well above the long-term average of about 50%.

Massom and Reid published a study last year that found that, since 1979, the Amundsen Sea region was seeing longer periods without ice, and more of the coastline was being exposed to open ocean conditions.

“It’s not just the extent of the ice, but also the duration of the coverage,” Massom says. “If the sea ice is removed, you expose floating ice margins to waves that can flex them and increase the probability of those ice shelves calving. That then allows more grounded ice into the ocean.”

The downturn in sea ice has now led the scientific community to wonder if the global climate crisis has also taken hostage of the frozen continent.

Knock-On Effects

One thing for certain, though, is that melting ice around Antarctica (and in the North Pole) could lead to a cascade of effects on the world’s climate patterns. Sea ice already plays a key role in regulating the world’s temperature, as its bright surface could reflect 50-70% of the Sun’s back into space. But as sea ice melts in the summer, it exposes the dark ocean surface which instead absorbs 90% of the sunlight, raising the temperature of the ocean, and the cycle of melting-warming intensifies.

Changes in the amount of sea ice also disrupt the ocean’s normal circulation. New research by Australian scientists suggests that Antarctica’s melting sea ice could slow down the current in the deepest parts of the ocean by 40% in three decades. This, according to the study, would lead to a rapid slowdown of a major global deep ocean current by 2050 that could alter the world’s climate for centuries and accelerate rising sea levels.

Matt England, of the University of New South Wales and a co-author of the study, said “the whole deep ocean current was heading for collapse on its current trajectory.”

“In the past, these circulations have taken more than 1,000 years or so to change, but this is happening over just a few decades. It’s way faster than we thought these circulations could slow down,“ England told The Guardian. “We are talking about the possible long-term extinction of an iconic water mass,” he warned.

While the study did not attempt to explain or quantify the knock-on effects, the authors believe the slowdown would “profoundly alter the ocean overturning of heat, fresh water, oxygen, carbon and nutrients, with impacts felt throughout the global ocean for centuries to come”.

A collapse of unthinkable proportions also looms in the more climate-sensitive Arctic, which is facing what scientists call a “terminal” loss in sea ice during summer months. This, according to a new State of the Cryosphere report, could arrive within a decade and cannot be avoided.

“Disappearance of sea ice will open up the dark Arctic ocean, which will absorb – rather than reflect – heat, causing global heating to escalate further. It will also upend the region’s ecosystem, harming everything from algae to large animals such as seals and polar bears that need the sea ice for hunting,” the authors wrote.

Mounting Climate Crisis

Perhaps the biggest question is what the loss of Arctic ice means for weather patterns in the rest of the world, NSIDC director Mark Serreze told Bloomberg. “More than anything else, weather patterns are driven by the planet’s attempt to equalize temperature differences between higher and lower latitudes.”

Twila Moon, deputy lead scientist at the NSIDC, also believes the environmental conditions in the Arctic are having a profound impact on weather systems across the world. The North and South poles act as the “freezers of the global system,” helping to circulate ocean waters around the planet in a way that helps to maintain the climates felt on land, Moon told ABC News back in 2021.

“What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic,” added climate scientist Jessica Moerman, currently vice president of science and policy at the Evangelical Environmental Network.

The jet stream, a band of strong winds moving west to east created by cold air meeting warmer air, helps to regulate weather around the globe. But as temperatures in the Arctic warm, the jet stream, which is fueled by the temperature differences, weakens, Moerman said.

Rather than a steady stream of winds, the jet stream has become more “wavy,” allowing very warm temperatures to extend usually far into the Arctic and very cold temperatures further south than usual, Moon of NSIDC added.

“These cold air outbreaks are really severe,” said Moerman. A study published in Science found that the variability in the climate in the Arctic, specifically the weakening of the Polar Vortex, which keeps cold air closer to the poles, likely led to the Texas freeze in February 2022.

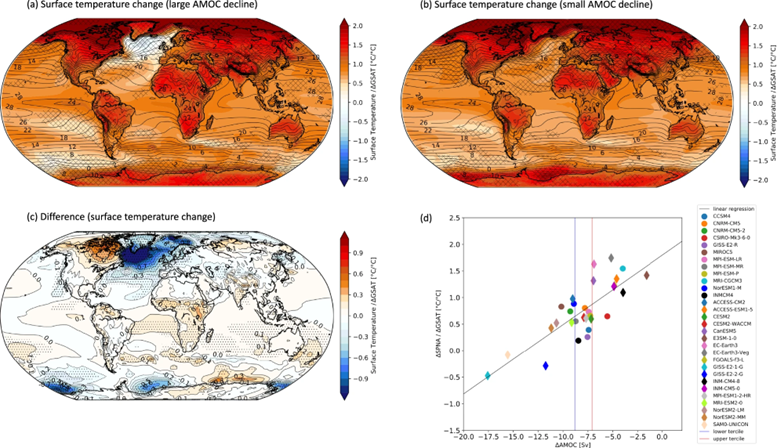

And as the climate becomes more unpredictable and unstable, so does the ocean’s water circulation. The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a large system of water currents that circulates water from north to south and back in a long cycle within the Atlantic.

This system of deep-water circulation, sometimes referred to as the Global Ocean Conveyor Belt, sends warm, salty Gulf Stream water to the North Atlantic, where it releases heat to the atmosphere and warms Western Europe. The cooler water then sinks to great depths and travels all the way to Antarctica and eventually circulates back up to the Gulf Stream (see below).

New research reveals this key cog in the global ocean circulation system hasn’t been running at peak strength since the mid-1800s, and is currently at its weakest point in the past 1,600 years!

Normally, it takes an estimated 1,000 years for a parcel (any given cubic meter) of water to complete its journey along the belt, but now it may take significantly longer.

According to a study published in leading science journal Nature, the AMOC has weakened over the past 150 years by approximately 15-20% due to the influx of freshwater from melted ice entering the system.

The last time the AMOC collapsed was the late 1300s to 1400s, which overlapped with the Little Ice Age when vast amounts of ice were flushed out into the North Atlantic, cooling its waters and diluting their saltiness, and ultimately triggering a substantial global cooling.

“What is common to the two periods of AMOC weakening — the end of the Little Ice Age and recent decades — is that they were both times of warming and melting,” said Dr. David Thornalley, a senior lecturer at the University College London and lead author.

According to study co-author Dr. Jon Robson, a senior research scientist from the University of Reading, the new findings hint at a gap in current global climate models. “North Atlantic circulation is much more variable than previously thought,” he said, adding that “it’s important to figure out why the models underestimate the AMOC decreases we’ve observed.”

Another study published in the same issue of Nature looked at climate model data and past sea-surface temperatures and found that AMOC has been weakening more rapidly since 1950 in response to recent global warming.

Together, these two studies provide complementary evidence that the present-day AMOC is exceptionally weak, which could have serious implications for Europe’s weather as well as the rest of the world.

Scientists believe that if the system continues to weaken, it could disrupt weather patterns from the United States and Europe to the African Sahel, and cause a more rapid increase in sea level on the US East Coast.

“Due to its role as a heat carrier, if the AMOC slows down then the northward heat transport is reduced and that leads to a cooling in the subpolar North Atlantic,” said Levke Caesar from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, lead author of the second study.

“Due to a more complex interaction between the southward deep water flow of the AMOC with the bottom topography of the ocean, a reduced AMOC is also associated with a northward shift of the Gulf Stream which then leads to the warming east of the US coast,” she explained to Carbon Brief.

“Because of its importance to the Intertropical Convergence Zone, AMOC slowdown would lead to large changes in precipitation in the tropics, including in Central and South America, India, South East Asia and parts of Africa,” said Spencer Jones, a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Oceanography at Texas A&M University.

Perhaps in a few years, the unusual weather we are experiencing today may not seem too odd anymore, regardless of where we are in the world.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.