Falling dollar not enough to lift commodities higher

2020.08.14

Commodity prices rise and fall with economic conditions. Conventional wisdom has it that commodities tend to do well during late expansions and early recessions. As the economy slows, interest rates are cut to stimulate the economy, the US dollar falls and demand for commodities, which are priced in USD, goes up, along with commodity prices. Stocks and bonds on the other hand don’t perform well during recessions.

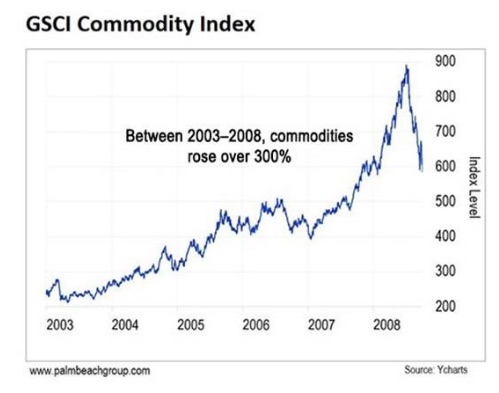

A commodities “supercycle” can happen in the late stages of an economic expansion, where growth is running so hot that companies can’t produce enough commodities to keep up with demand. The last commodities supercycle was between 2004 and 2008. From the bottom in 2003 to the peak in 2008, commodities rose over 300%.

The commodities supercycle of the 2000s collapsed in the Great Recession of 2008, then resumed from 2009 to 2011. It ended in the bear market of 2011-15.

Could a commodities supercycle happen again? The idea at first glance seems hopelessly idealistic in the context of the global pandemic, which has not only crushed economic growth, but had an adverse effect on consumer spending, manufacturing, and supply chains, which move raw, semi-processed and finished goods around the world.

But there are signs of a metal commodities revival. Gold and silver have been on a tear since mid-March. The usual suspects behind the surges of both metals are worrisome covid-19 infections, geopolitical concerns especially US-China tensions over trade and the South China Sea, inflation expectations on the back of (seemingly) unlimited monetary stimulus, and low interest rates worldwide.

Bullion prices have climbed 28% year to date, as investors choose gold as a safe haven amid widespread economic uncertainty created by the pandemic. They believe gold will hold its value better than other assets such as stocks and bonds.

Silver in July gained an astonishing 35%, as investors sought shelter from pandemic turmoil and low or negative interest rates, while industrial demand for the metal recovered in some parts of the world.

And certain industrial metals, despite lower demand, have done quite well in the new covid-19 normal. On July 21 copper futures flirted with $3 a pound, hitting a two-year high of $2.97, after an agreement of a large economic stimulus plan in Europe and optimism about a covid-19 vaccine combined with worries about pandemic-hit supply from top producers Chile and Peru.

The boom, naturally, is being driven by top commodities consumer China, as the country’s infrastructure and manufacturing sectors recover from the February-April covid-19 slump.

Refined copper imports into the country hit an all-time high of 494,000 tonnes in June and preliminary figures point to a new July record of 530,000t.

Imports of unwrought aluminum, a mixture of primary metal and alloy, surged to 254,000 tonnes in June.

Pushing the commodities complex higher is a weak US dollar. Since its mid-March high, the greenback has fallen nearly 10%, reversing almost half of the appreciation of the last 10 years, in only a few months. The chief culprit has been the US Federal Reserve’s low interest rate policy, which has cut the demand for dollars flowing to safe havens like US government bonds.

We wanted to know, is a falling dollar all that commodities need to rise again, in a once-in-a-generation commodities supercycle? If not, what would it take?

Dollar weakness

Jesse Felder raises the question in his The Felder Report blog. In it he writes,

If the dollar is to decline again in a major way as a result of the rapid debt accumulation met with money printing for the explicit purpose of stoking inflation, commodities could prove be the best way to play it. Better yet, considering just how cheap and out of favor commodities-focused equities have now become, they could present investors with a generational opportunity today.

Hat tip to Mr. Felder for being the inspiration for this article.

A weak dollar usually means stronger commodities prices. Because the USD is the reserve currency and commodities are traded in dollars, the value of the dollar is of crucial importance in determining the value of the commodity in question. Take the case of a low dollar. When the dollar drops it takes less of another currency to buy dollars needed to purchase the commodity, so the demand for that commodity will increase. The inverse happens when the dollar strengthens.

As the dollar barreled along during the mining bear market of 2012 to 2016, commodity prices slumped.

We now see the opposite happening. When the pandemic went global in March, the dollar strengthened on the back of safe-haven flows into US Treasuries. By May, all those gains had been erased, as the US Federal Reserve poured trillions worth of liquidity into financial markets.

The dollar’s two-year low against the euro in July prompted many headline-writers to herald the end of the buck as the world’s reserve currency. We’ve written on that subject extensively and won’t get into it in this article. Recent commentaries are dismissive of the idea.

What we can say is that the dollar is likely to be pressured, so long as the United States battles the coronavirus, with further depreciation likely even if the economy starts to recover.

And that will be good for commodities. With some $26 trillion in national debt, a federal deficit approaching $4 trillion, and a debt to GDP ratio over 100%, the Fed can’t raise interest rates without imposing a crippling cost of borrowing. Low interest rates imply a weaker currency.

Also consider: a slumping dollar boosts US producers’ international and domestic competitiveness. It’s possible that the US economy could get back on track through an export-driven recovery that also sees rising commodity prices.

Demand

Other than a low dollar, the other big factor pushing mined commodities higher, is demand. This contains a number of moving parts. First there is China, the world’s largest metals consumer by far. Any discussion of commodity prices has to include what’s happening in China.

Second is infrastructure.

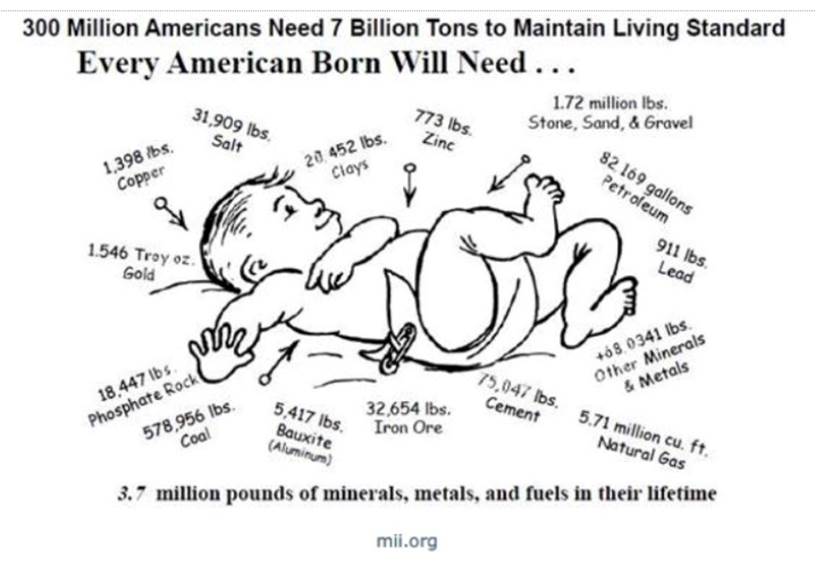

Commodities are the building blocks of the infrastructure we all rely on for daily life. This includes roads, bridges, ports, railways, commercial buildings, 5G installations, sewers, water lines, etc. Iron ore and coking coal are the chief ingredients in steel, copper is used in construction, telecommunications and transportation, and nickel is used to make stainless steel. Agricultural commodities feed the world and satisfy our modern-day tastes. Without staples like wheat, rice and corn, billions of people would die. Coffee, sugar and tobacco aren’t life or death, but doing without them would be a hardship for many. These are just a few examples.

Three of the top five countries most in need of new infrastructure are in Asia: China, India and Japan. China will need about a third of the total, $28 trillion. The United States will have the largest gap in infrastructure spending – $3.8 trillion – despite President Trump’s 2016 campaign pledge to fix America’s crumbling cities.

At AOTH we have been calling for a major infrastructure program to kickstart the sputtering US economy. Something on par with President Roosevelt’s New Deal package of spending measures and so-called progressive legislation that, along with the ramp-up in military spending to handle World War II, helped the United States out of the Great Depression. Given the current state of the US economy, any future infrastructure program may in fact dwarf FDR’s New Deal.

Arguably, a major component should be “clean and green”, including investments in electric vehicle/ charging infrastructure, renewable energies and expansion of 5G/ broadband. China and Europe have already stated their intentions in plowing billions into traditional and clean-tech infrastructure programs, to help their economies to recover from the pandemic.

And third is population.

Since 1950, the world’s population has gone from 2.5 billion people to 7.5 billion. No less than 75 million people a year are added to this number.

According to the United Nations, the world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by the year 2050. A study in the journal Bioscience suggested that to feed that number of people, global food production will need to increase by 45%.

The countries with the most natural resources are, in order: China, Saudi Arabia, Canada, India, Russia, Brazil, the US, Venezuela, the DRC and Australia.

Another 2.1 billion people will be added to the world between now and 2050. Most will not be Americans but they are going to want a lot of things that we in the Western developed world take for granted – electricity, plumbing, appliances, AC, etc. What if all these new consumers were to start consuming, over the next 10 years, just like an American? What’s going to happen to the world’s mineral resources if a billion more “Americans” are added to the consuming class? Here’s what each of them would need to consume, per year, to live the American lifestyle…

The question is, and we’ve asked it before, will everyone be able to buy enough resources to live like an American? The answer is a resounding no!

Another way to look at this, is based on population growth statistics – by 2050 the world economy will be four times larger than today. To have the same per-capita consumption of Canada would require a world economy 15 times its current size!

The numbers may boggle the mind, but they also focus it on the need for exploring for, and mining, a whole lot more commodities that go into the sustenance of our daily lives, including copper, silver, iron ore, aluminum, zinc, nickel, rare earths, and specialty metals like manganese and vanadium.

Rick Rule, President and CEO of Sprott US Holdings, has an optimistic view of the capacity of human beings to improve their lot in life, through consumption.

“As a species we have managed to survive and we will thrive,” Rule, a popular investment conference speaker, said earlier this year at The Money Show.

He notes there are bullish factors underlying the upward trend in precious metals and commodity markets – one being what he calls “the ascent of man” who has survived and prospered through famines, poverty, war, turmoil and disease.

As poor people do better, there will be a need for more natural resources. Rule points out that the poorest 2 billion people in the world are getting richer faster than at any point in history.

“There are still some 1.7 or 1.8 billion people around the world that don’t have reliable electrical service,” he said. “However, it is anticipated that the world will be fully wired within 20 years.”

Another key point – when poor people gain more spending power they tend to buy “things” made from natural resources, versus the wealthier who already have what they need and tend to spend their discretionary income on services like vacations.

Global material use

For the past 50 years, there has never been a period where demand for natural resources did not increase. How many businesses can say that? Sure, metals prices have fluctuated, but the need for metals has not diminished. In fact, mining is becoming even more important, as the transportation system goes from fossil-fuel-powered to electric, requiring a new mix of metals for batteries and components. Among the most in-demand are lithium, copper, cobalt, graphite and manganese. There is also the switch from oil and natural gas to renewables, requiring millions of ounces of silver for solar panels and thousands of tonnes of rare earths for wind turbines.

Electrification

The electrification of our global transportation system will require a change hitherto unprecedented in the history of civilization. Not even the shift from horse and buggy to the crank-start Ford Model T can compete with what it will take to electrify the billion-plus cars on the planet’s roads.

Along with the immense political will needed for other countries to legislate electrics-only targets, and the technology required to make EVs that match the range and power of gas or diesel-fueled models, and can achieve price parity with them, consider the amount of raw materials that will be needed to fuel electrics.

The electric motor in a battery-powered electric vehicle contains copper, steel and permanent magnets, the latter made of the rare earths neodymium, praseodymium and dysprosium. An EV’s lithium-ion battery has three parts – an anode, a cathode and electrolyte. The electrolyte is made of lithium salts, the anode from graphite, and the cathode material varies, between NCA (nickel, cobalt, aluminum), LMO (manganese) and NMC (nickel, manganese, cobalt).

A Tesla Model S contains 54 kilograms of graphite and 63 kilograms of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) – more than the lithium in over 10,000 cell phones. An average EV has 83 kilograms of copper and between 4 and 30 kg of cobalt.

China

Over the last five decades or so, mineral extraction has tripled – and accelerated since 2000 – as the two largest new economies, China and India, required huge amounts of raw materials through the process of urbanization and modernization.

The last commodities supercycle, 2004-15 (minus the Great Recession of 2008-11), was driven primarily by China’s thirst for minerals and energy. Beijing unleashed a mega stimulus package after the 2008 financial crisis, much of it delivered in the form of direct government spending on infrastructure. Some $560 billion was poured into road & rail construction and property development, driving up demand for everything from iron ore to copper to diesel.

China is the first country to come out of the pandemic, virtually unscathed (although accurate numbers are hard to come by). As mentioned the country is importing record amounts of copper, and its economy returned to growth in the second quarter after shrinking 6.8% in Q1.

The big question is, can we expect China to lead commodities growth to the same extent as last time?

A targeted boom

The short answer appears to be no. We get a pretty good idea as to how much China is willing to spend and for what purposes, from this year’s meeting of the National People’s Congress.

As The Financial Times reports, Premier Li Keqiang announced an $853 billion stimulus package to stabilize the economy from coronavirus disruptions, increasing demand for raw materials in key sectors such as construction and transport.

However, it will not be as steel-intensive as previous packages with copper likely to benefit the most from the new infrastructure spend. Traditional projects such as bridges, roads, and airports were not mentioned.

Tellingly, while China’s economy raced along at double-digit GDP growth during the last commodities boom, Beijing has abandoned its growth target for 2020, apparently accepting it will be well below the 6% achieved in recent years.

Rather than firing “fiscal bazookas” like in 2009-11, which misallocated resources and gave rise to a property bubble, new spending will be funneled into three priorities: new infrastructure, new urbanization and other large projects. The FT states,

This is in line with China’s medium-term strategy to advance its economy through investment in science and technology. New infrastructure includes building next-generation information networks, 5G applications and charging facilities for new energy vehicles. New urbanization captures the upgrade of public facilities, including renovation of 39,000 old urban residential communities and installation of elevators in residential buildings. Big spending projects include improved water conservation and transport, with Rmb100bn earmarked for national railways.

World Oil agrees that China is unlikely to deploy a blanket stimulus this time around, quoting Michal Meidan, director of China research at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, who states:

“The focus seems to be on new infrastructure such as 5G and artificial intelligence, all of which are less commodity-intensive than the previous stimulus programs we’ve seen that have encouraged construction activities. The commodity rebound from February’s depressed levels is likely to continue as the economy recovers, but I doubt we will see a 2008-2009 style bounce.”

Peak BRI

What about that other colossal raw materials boon, China’s Belt and Road Initiative? According to an estimate by the Institute of International Finance, since 2013 China has agreed to US$690 billion in overseas investments and construction contracts in more than 105 countries.

The “Belt” part of the BRI, introduced by President Xi Jinping in 2013, refers to a network of overland road and rail routes and oil/ natural gas pipelines planned to run along the major Eurasian land bridges: China-Mongolia-Russia, China-Central and West Asia, China-Indochina peninsula, China-Pakistan, Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar. They’ll stretch from Xi’an in Central China through Central Asia, reaching as far as Moscow, Rotterdam and Venice.

The “Road” is a network of ports and other coastal infrastructure projects from South and Southeast Asia to East Africa and the northern Mediterranean Sea.

The Belt and Road Initiative is seen by proponents as an economic driver of proportions never seen before in human history. It would not only allow Asia to relieve its “infrastructure bottleneck” ie. an $800 billion annual shortfall on infrastructure spending, but bring less-developed neighboring nations into the modern world by providing a growing market of 1.3 billion Chinese consumers.

Opponents argue that is naive and the real intent of BRI is to carve new Chinese spheres of influence in Asia that will replace the United States, in-debt poor nations to China for decades, and restore China to its former imperial glory. At AOTH, we are in this camp.

While the value, according to Refinitiv, of belt and road projects exceeded $4 trillion in the first quarter of 2020, there are signs that momentum is slowing, partly due to the pandemic, and partly due to criticism from countries that have received loans from China.

The number of new projects in the first quarter fell 15.6% compared to the same period in 2019, with their total value down 64%. South China Morning Post reports,

Debt has been highlighted as a major concern because of China’s investments in developing countries that already have high levels of debt. Washington has called China’s belt and road lending a “debt trap”, saddling countries with debt that they will not be able to repay. A number of controversial Chinese investments in developing countries have raised questions about the sustainability of belt and road loans, and about whether such projects can ever generate enough money to pay off the debt…

Some analysts have said that the pandemic, coupled with slow domestic growth, may force China to scale back some of its belt and road projects.

Forbes wrote earlier this year that China’s failure to define what Belt and Road is, has led to Beijing losing control of the message. It notes that China’s overseas investment has declined sharply over the past three years, with Moody’s claiming this is due to an awareness of risks inherent in BRI projects:

Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Kyrgyzstan, among other countries have canceled, downsized, or postponed key BRI projects, and the initiative seems to be going through a period of retreat to an extent that some researchers are suggesting that we may have already seen “peak” Belt and Road.

Conclusion

At its present 93.11, the US dollar index (DXY) is at its lowest in two years. The currency is being debased amid unprecedented pandemic-related government spending, and too much borrowing at interest rates close to zero.

The buck’s retreat is also directly correlated to America’s failure to control the coronavirus.

Any economic recovery relies on the United States flattening its pandemic curve. Policymakers know this, and are acting accordingly, keeping interest rates at near 0% for the foreseeable future.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said the Fed will keep its monetary easing programs in place “until we’re very confident that the turmoil from the pandemic and the economic fallout are behind us.”

A worsening US economy will turn investors away from bonds and Treasuries – no more financing for US debt. The dollar will fall further and commodities will rise, including gold and silver, pushed higher by investment demand for gold-backed ETFs and physical metal.

Globally, the demand for commodities will continue to be muted by the economic fallout from the virus. The World Bank in its April ‘Commodity Markets Outlook‘said it expects substantially lower prices over 2020, with energy and metals commodities most affected by the sudden stop to economic activity and the serious global slowdown.

“This enormous shock to commodity markets and low oil prices could deliver a serious setback to developing economies and jeopardize the necessary investments in critical infrastructure that support long term growth and create quality jobs,” said Makhtar Diop, World Bank Vice President for Infrastructure.

However, amid the dark clouds there are shards of sunlight – most notably in metals that support “clean and green” infrastructure programs that governments are pushing for, as a way of re-fueling their tired economies. Copper and zinc in particular look promising.

Zinc posted its biggest weekly gain since 2016, 8.2%, largely due to an expansionary PMI reading (51.2) from China in June. Copper surged 33.5% from a 52-week low of $2.17 on April 21. Copper mining companies nearly doubled in value from a mid-March low, according to the Solactive Global Copper Miners Index, as Chinese smelters cranked up production.

Manufacturing growth in July was strongest in China, France, Italy, the UK and Brazil.

Battery metals that tie into vehicle electrification, and materials for renewable energy technologies, like copper, silver and rare earths, are practically certain to be in high demand, as will commodities needed to install 5G networks.

Maybe it won’t be a commodities super-cycle, but there will be pockets of growth, and that growth is likely to be significant, especially if government-led infrastructure roll-outs come to fruition.

In the meantime, we have precious metals.

The way we see it, gold has it made, whether economic growth picks up or it continues to muddle along, still pinned down by the coronavirus. In the current deflationary environment, gold is doing well because of all the drivers that make it such an attractive investment – a high global debt to GDP ratio from the combination of falling economic growth and rising national debts, owing to massive virus-related stimulus; growth of the M2 money supply lighting a fire under gold prices; continued low interest rates until at least 2022; a steady flow of safe-haven demand, due to the numerous global hot spots particularly with regard to a more belligerent China; and social/ economic chaos gripping the United States as it enters a presidential election.

Gold is also poised to gain in the likely event that all of this stimulus – at last count $18.4 trillion! – leads to inflation.

If inflation goes, say, above 3%, yet interest rates remain near zero, that would create another bullish condition for gold – negative real rates (interest rates minus inflation). When US Treasury bond yields turn negative, investors typically rotate their funds out of bonds, into gold.

As for silver, we have recently seen the gold-to-silver ratio decline, from over 125:1, to the current 71.7:1, meaning it takes 71.7 ounces of silver to buy one ounce of gold. Historically, the ratio is 55:1, so silver is still undervalued compared to gold.

We have the same bullish indicators for silver as for gold, in terms of safe-haven demand inciting investors to park their money in silver bullion, silver ETFs or silver mining stocks, and the fact that silver is not subject to inflation like paper currencies.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Facebook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.