Extreme weather arrives early in Western Canada; another hot, dry summer expected -Richard Mills

2023.05.10

Residents of rural British Columbia and Alberta are dealing with forest fires and flooding early on, in what has become an annual season of extreme weather in Western Canada.

A week of record heat forced thousands to evacuate their homes as wildfires raged across Alberta and northeastern BC, and rapid snow melt triggered flooding across the Interior.

The entire 7,000 population of Drayton Valley, AB, was told to leave, among nearly 30,000 Canadians displaced according to media reports on Sunday, May 7. As of this writing, there were 98 active wildfires burning in Alberta, and 62 in British Columbia.

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith called the situation “unprecedented”, telling a news conference that the Canadian province “has been experiencing a hot, dry spring and with so much kindling, all it takes is a few sparks to ignite some truly frightening wildfires.”

Source: Twitter

The province is now under a state of emergency, which allows the government a higher level of co-ordination with municipalities, organizations and businesses to support evacuated residents. It also permits 24/7 monitoring of the situation, access to emergency funds and the ability to mobilize additional support.

Firefighters from Ontario and Quebec arrived on Saturday and an incident management team came Sunday, reportedly to take over the wildfire near Edson, located about mid-point between Jasper and Edmonton on Highway 16. More support is expected from Montana.

Source: Alberta Wildfire

Improved weather conditions including scattered showers and lower temperatures, Sunday, helped firefighters. Winds were expected to ease Monday and Tuesday. However, the relief is expected to be short-lived; by this weekend, some parts of BC could see temperatures reach as high as 32 degrees.

A warming trend is also happening on the other side of the continent. Big cities in the US northeast are expected to experience a temperature rise from the mid-70s F to the low-80s through the week.

In NE British Columbia, two wildfires in one day nearly doubled in size. CTV News reported the Boundary Lake fire on Sunday was estimated at about 5,900 hectares, with the Red Creek fire at 2,800 ha.

Evacuation orders are in place for areas surrounding both fires.

The Prince George Fire Centre is currently responding to 4 “fires of note”, CBC News reported on Monday morning.

BC wildfire situation as of Monday afternoon. Wildfires of note are seen as red flames, out of control fires are in red, being held in yellow, under control in green. Source: BC Wildfire Service.

Western Canada had been enduring a cold spring, but the rapid onset of unseasonably high temperatures in places 10 to 15 degrees above average for early May, is causing both fires and flooding.

“Warm temperatures in the Interior have accelerated snowmelt and caused increased pressure on rivers and creeks,” the Ministry of Emergency Management said in a statement, via Reuters.

Among the towns worst hit by waterways spilling over their banks, are Cache Creek and Grand Forks. On the television news over the weekend, residents were furiously filling sand bags to hold the flood waters back.

In Grand Forks, Sunday, 34 families began returning home, as the state of local emergency was rescinded due to peaking water levels. However, according to EmergencyInfoBC, as of Monday, May 8, evacuation orders remain in place for the Village of Cache Creek, the Okanagan Indian Band, and the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary. Evacuation alerts are active for the Regional District of Central Kootenay, the RDKB, and the Regional District of Okanagan-Similkameen.

An evacuation order means you are at risk and must leave the area immediately. An evacuation alert means you should be ready to leave on short notice.

In fact the worst may be yet to come. According to the B.C. River Forecast Centre, affected areas will remain vulnerable throughout the week as snow continues to melt.

“We’re still early for the big rivers, like the Fraser river, the Thompson river, those tend to peak a little bit later in the season so we’re anticipating to watch those closely over the coming weeks,” said Dave Campbell, the head of B.C. River Forecast Centre, as reported by CTV News.

California drought far from over

Beyond Western Canada, some are speculating that the 1,200-year drought in California may be over, considering the amount of rainfall and snow the state received this past winter. If only. AOTH found evidence to suggest that drought conditions are likely to remain due to low groundwater and river levels, particularly the Colorado River which provides drinking and irrigation water to millions.

According to NPR, while the amount of water in reservoirs plummeted in recent years, they now have more than they can hold. California was hit by 12 “atmospheric rivers” this past winter, that led to evacuation orders, rising rivers and broken levees. In some parts of the Sierra Nevada, more than 55 feet of snow has fallen.

There are three issues.

The first has to do with groundwater. Underground aquifers have supplied up to 60% of California’s water during drought years, but usage has been largely unregulated and over the decades levels have fallen dramatically. The Central Valley’s groundwater hasn’t been replenished after previous droughts and over the past three years, more than 2,000 household wells have run dry.

“We’re not out of a drought,” NPR quotes Susana De Anda, executive director of the Community Water Center, an environmental justice organization in the Central Valley.

To be sure, efforts are underway to improve the situation. Farmers and water managers want to divert floodwaters into storage-ready basins, that will eventually allow the trapped water to find its way into the natural aquifer system hundreds of feet below.

A seven-year-old law limiting the the amount of water than can be pumped, started taking effect in 2021.

But water users writing plans for keeping groundwater use in balance with supply won’t be implemented until 2040. In the meantime, California’s other source of water, the Colorado River, is still in drought, partially due to climate change shrinking the snow pack that feeds it.

The 20-year-old drought has caused two huge reservoirs filled by the Colorado, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, to plummet. According to NPR, the seven states that currently use the river have long made claim to more water than is available. Now that water levels are perilously low, they are in emergency negotiations over cutbacks to their water supply, but are struggling to agree.

The third issue is the droughts of the future. As the planet warms, California’s dry spells are expected to get worse, putting even more strain on its water supply. The state saw plenty of rain and snow this past winter, but next winter, who knows? With the prospect of another drought likely, California’s water managers would be wise to implement conservation measures and try to save whatever water they have.

The forecast calls for heat

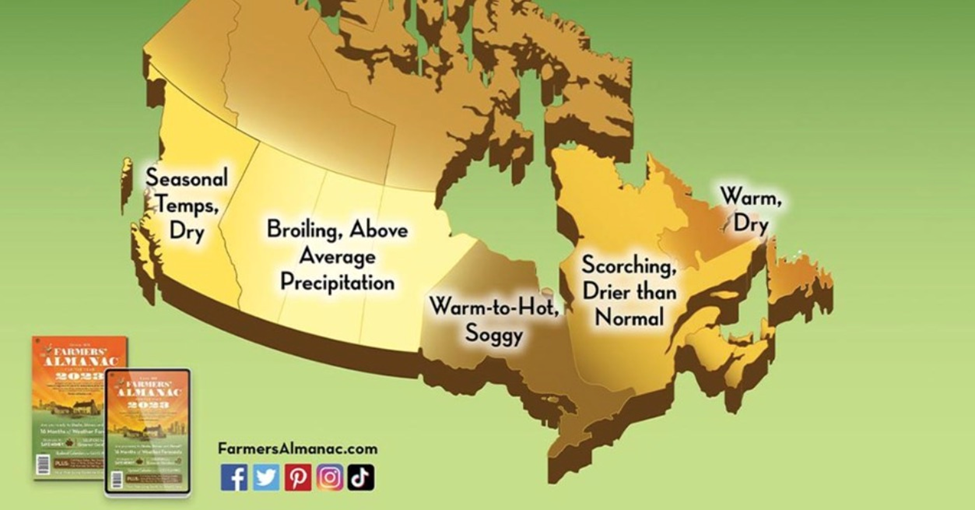

Turning back to Western Canada’s weather, if you had a crystal ball, what would it look like? Of course we don’t have one, but we do have the next best thing to it: the Farmer’s Almanac.

The go-to source for weather predictions for over two centuries, is forecasting that the Canadian summer will be a scorcher.

According to the almanac, via New Market Today, most of the country is in for a “warmer-than-normal” summer, which officially starts on June 21 and lasts until early September. Temperatures could rise above 32C and some regions could experience 40C, when humidity and heat indices (“feels like” temps) are factored in.

The forecast predicts British Columbia will see seasonal temperatures while Alberta and the other prairie provinces could experience a serious heatwave. The map below shows consistent warmth across the country, but quite a bit of variation in precipitation. The almanac says Central Canada will see above-normal rainfall, with parts of the Rockies, Prairies and Great Lakes likely to see occasional bouts of heavy rain and thunderstorms. In contrast, Quebec and parts of the Maritimes should expect below-normal precipitation, while Newfoundland-Labrador can look forward to a generally warm and dry summer.

La Niña and El Niño

More scientifically, one of the most important predictors of weather we can look at are the climate patterns known as La Niña and El Niño.

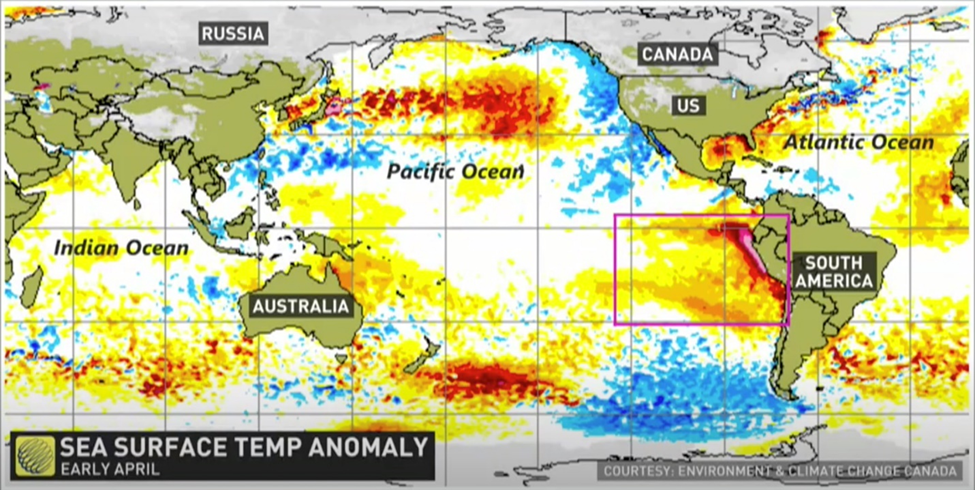

It’s been well-established that warmer, or colder-than-average ocean temperatures have an influence on weather. To see how this works, watch a video or read the following by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA):

During normal conditions in the Pacific ocean, trade winds blow west along the equator, taking warm water from South America towards Asia. To replace that warm water, cold water rises from the depths — a process called upwelling. El Niño and La Niña are two opposing climate patterns that break these normal conditions. Scientists call these phenomena the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle. El Niño and La Niña can both have global impacts on weather, wildfires, ecosystems, and economies. Episodes of El Niño and La Niña typically last nine to 12 months, but can sometimes last for years. El Niño and La Niña events occur every two to seven years, on average, but they don’t occur on a regular schedule. Generally, El Niño occurs more frequently than La Niña…

During El Niño, trade winds weaken. Warm water is pushed back east, toward the west coast of the Americas…

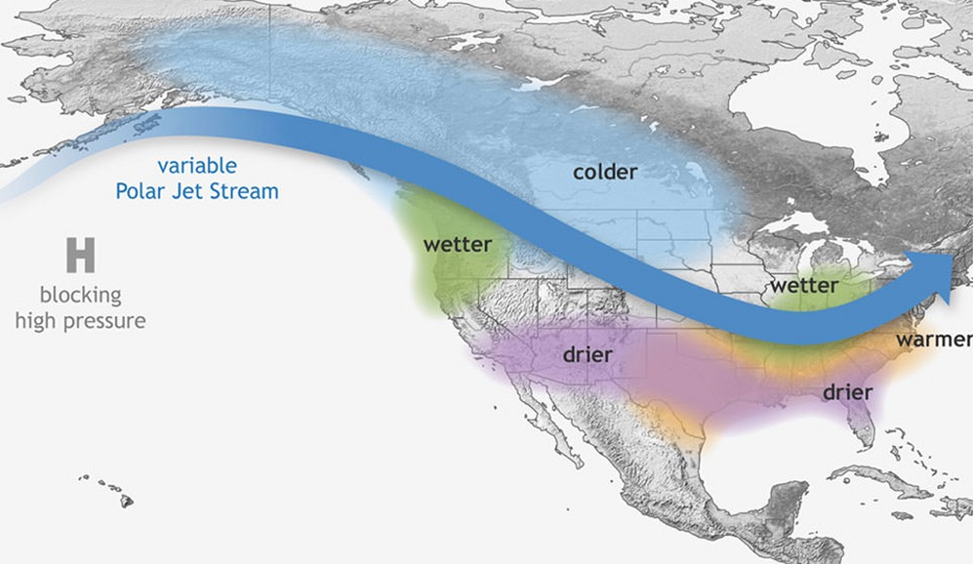

El Niño can affect our weather significantly. The warmer waters cause the Pacific jet stream to move south of its neutral position. With this shift, areas in the northern U.S. and Canada are dryer and warmer than usual. But in the U.S. Gulf Coast and Southeast, these periods are wetter than usual and have increased flooding…

La Niña has the opposite effect of El Niño. During La Niña events, trade winds are even stronger than usual, pushing more warm water toward Asia…

These cold waters in the Pacific push the jet stream northward. This tends to lead to drought in the southern U.S. and heavy rains and flooding in the Pacific Northwest and Canada. During a La Niña year, winter temperatures are warmer than normal in the South and cooler than normal in the North. La Niña can also lead to a more severe hurricane season.

A May 3 update from the World Meteorological Association states that the likelihood of El Niño happening later this year is increasing. This would result in higher global temperatures.

According to the WMO report, an unusually stubborn three-year La Nina pattern has now ended, and we are currently in a neutral state, of neither El Niño nor La Niña.

There is a 60% chance of the climate pattern transitioning from neutral to El Niño between May and July, increasing to 70% in June-August, and 80% between July and September.

In a couple of weeks The Weather Network forecasts strong westerly winds pushing warmth back to the central Pacific will speed up the development of El Niño. Last time there was a strong El Niño summer, in 2015, every Canadian city had at least one month above normal.

“The development of an El Niño will most likely lead to a new spike in global heating and increase the chance of breaking temperature records,” said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas.

He added: “The world should prepare for the development of El Niño, which is often associated with increased heat, drought or rainfall in different parts of the world. It might bring respite from the drought in the Horn of Africa and other La Niña- related impacts but could also trigger more extreme weather and climate events.”

Most forecasters believe if El Niño kicks in across the Pacific Ocean, western Canada could be quite dry in coming months. (The Financial Post) According to North American Drought Monitor, large swaths of BC, Alberta and Saskatchewan saw drought through March, including nearly half of Alberta (44%) as of April 22.

Climate disruptors

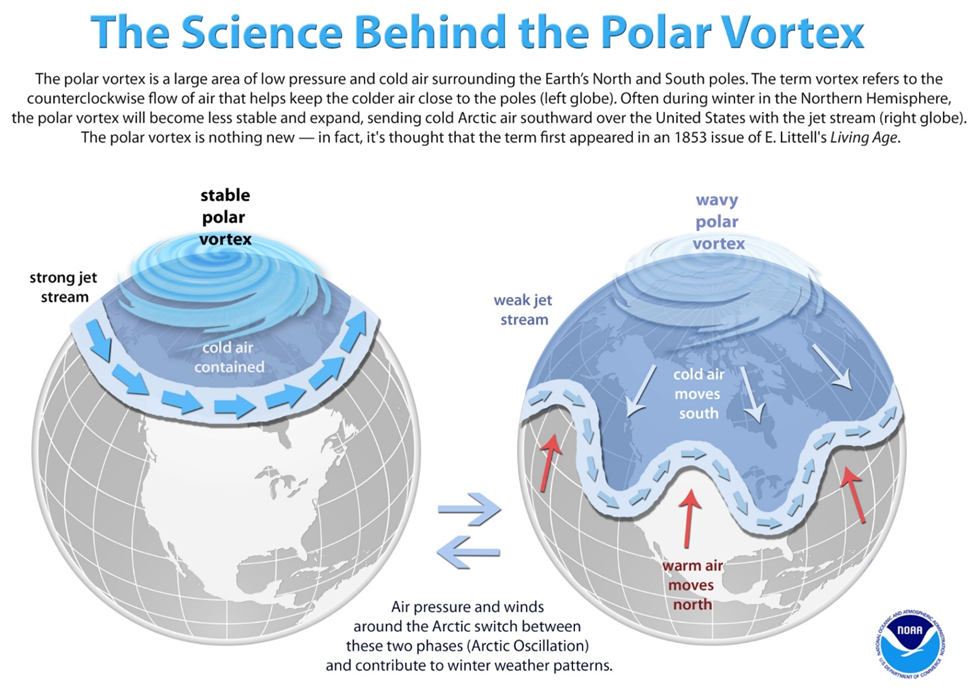

Other natural phenomena associated with climate change are thought to be contributing to above-average temperatures. One is the polar vortex, another is the disruption of normal ocean currents; both are related to the loss of polar sea ice.

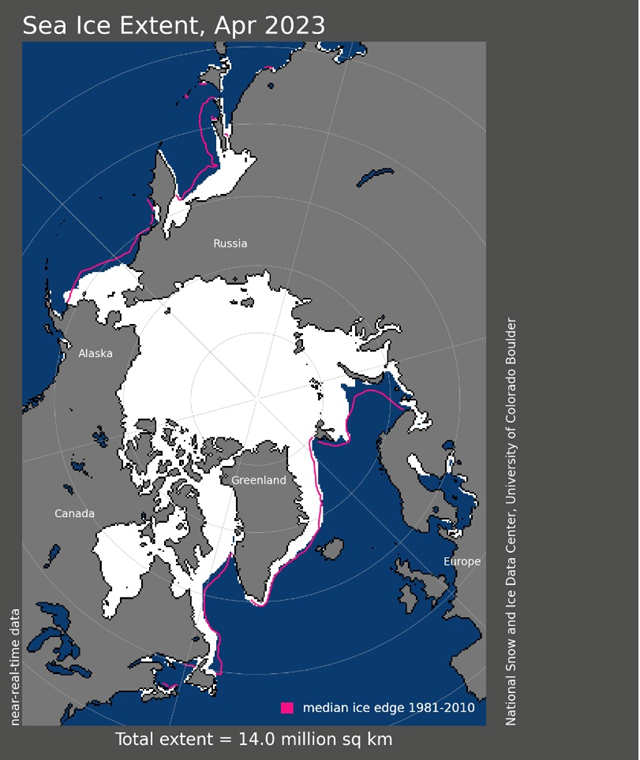

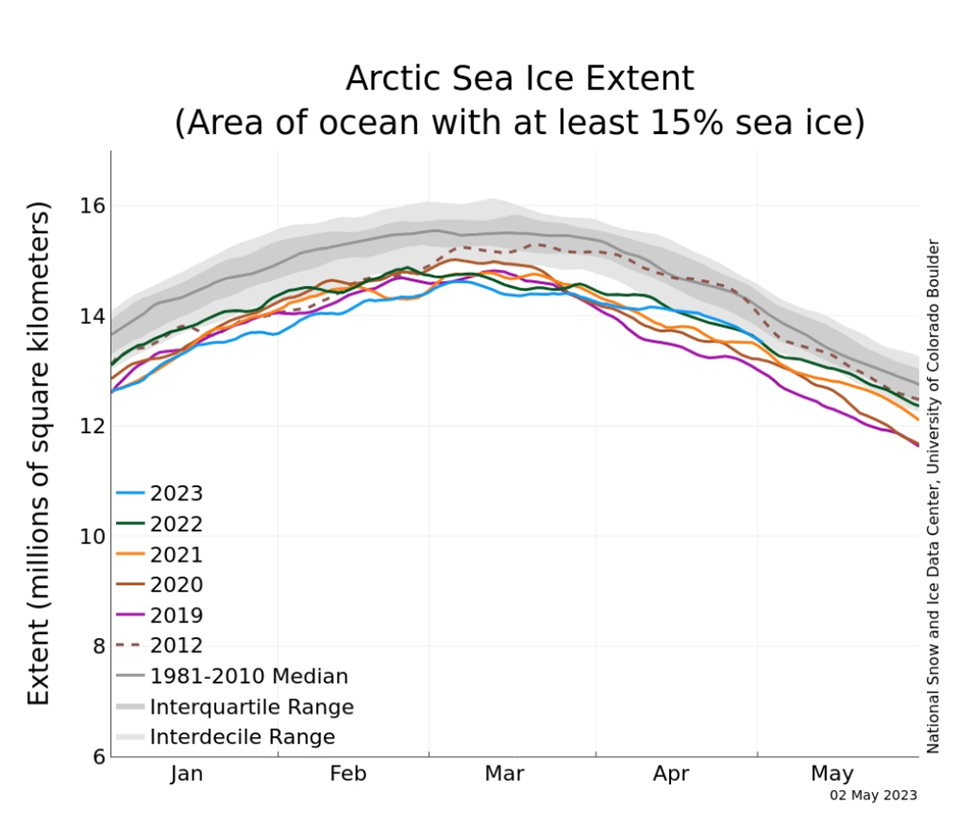

Scientists have found that the Arctic is heating up four times faster than the rest of the world. Much of this has to do with ice reduction.

The Arctic Ocean is mostly covered with a layer of ice. But as the planet warms, the sea ice begins to dissipate and exposes more of the ocean surface, allowing heat to escape. As more ice vanishes from the sea, Arctic temperatures rise faster, which in turn makes the remaining ice vulnerable to melting.

Data from the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC) shows this past April’s average Arctic sea ice extent was 13.99 million square kilometers, tied with 2004 as the 10th lowest April in the satellite record.

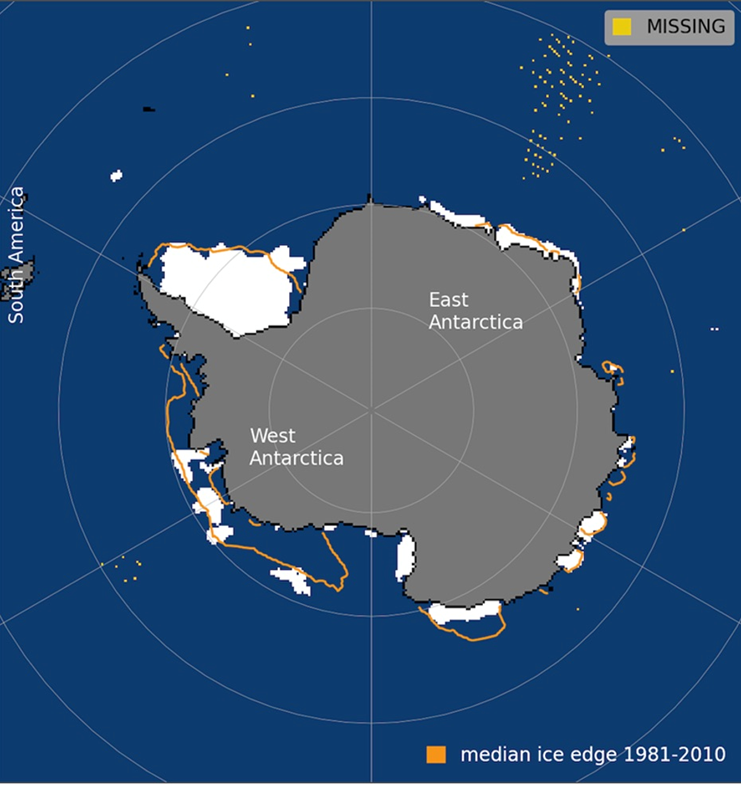

The South Pole, similar to its northern counterpart, is warming faster than the global average at three times the pace.

A recent study revealed that Antarctic sea ice hit its lowest levels ever recorded. In the southern hemisphere summer of 2022, the amount of sea ice dropped to below 2 million square kilometers for the first time since satellite tracking began. A year later, a new record low of 1.79 million square kilometers was set.

One major area of concern is a marked loss of ice around the Amundsen and Bellinghausen seas off West Antarctica. Even as the average amount of sea ice around the continent grew up to 2014, these two neighboring seas saw losses, satellite data shows.

That’s important because the region is home to the vulnerable Thwaites glacier — known as the “doomsday glacier” because it holds enough water to raise sea levels by half a meter.

Indeed, melting ice around Antarctica and in the North Pole could lead to a cascade of effects on the world’s climate patterns. As mentioned, sea ice already plays a key role in regulating the world’s temperature, as its bright surface reflects 50-70% of the sun’s light back into space. But as the ice melts in summer, it exposes the dark ocean surface, which instead absorbs 90% of the sunlight, raising the temperature of the ocean, and the cycle of melting-warming intensifies.

A collapse of unthinkable proportions looms in the climate-sensitive Arctic, which is facing what scientists call a “terminal” loss in sea ice during summer months. This, according to a new State of the Cryosphere report, could arrive within a decade and cannot be avoided.

“Disappearance of sea ice will open up the dark Arctic Ocean, which will absorb — rather than reflect — heat, causing global heating to escalate further. It will also upend the region’s ecosystem, harming everything from algae to large animals such as seals and polar bears that need the sea ice for hunting,” the authors wrote.

Changes in the amount of sea ice also disrupt the ocean’s normal circulation. New research by Australian scientists suggests that Antarctica’s melting sea ice could slow down the current in the deepest parts of the ocean by 40% in three decades. This could alter the world’s climate for centuries and accelerate rising sea levels.

Matt England of the University of New South Wales, and a co-author of the study, said “the whole deep ocean current is heading for collapse on its current trajectory.”

“In the past, these circulations have taken more than 1,000 years or so to change, but this is happening over just a few decades. It’s way faster than we thought these circulations could slow down,“ England told The Guardian. “We are talking about the possible long-term extinction of an iconic water mass,” he warned.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a large system of water currents that circulates water from north to south and back in a long cycle within the Atlantic.

This system of deep-water circulation, sometimes referred to as the Global Ocean Conveyor Belt, sends warm, salty Gulf Stream water to the North Atlantic, where it releases heat to the atmosphere and warms Western Europe. The cooler water then sinks to great depths and travels all the way to Antarctica and eventually circulates back up to the Gulf Stream (see below).

New research reveals this key cog in the global ocean circulation system hasn’t been running at peak strength since the mid-1800s, and is currently at its weakest point in the past 1,600 years!

According to a study published in the science journal ‘Nature’, the AMOC has weakened over the past 150 years by approximately 15-20% due to the influx of freshwater from melted ice entering the system.

The last time the AMOC collapsed was during the late 1300s to 1400s, which overlapped with the Little Ice Age, when vast amounts of ice were flushed out into the North Atlantic, cooling its waters and diluting their saltiness, ultimately triggering a substantial global cooling.

Perhaps the biggest question is what the loss of Arctic ice means for global weather patterns. “More than anything else, weather patterns are driven by the planet’s attempt to equalize temperature differences between higher and lower latitudes,” NSIDC director Mark Serreze told Bloomberg.

Twila Moon, deputy lead scientist at the NSIDC, also believes the environmental conditions in the Arctic are having a profound impact on weather systems. The North and South poles act as the “freezers of the global system,” helping to circulate ocean waters around the planet in a way that helps to maintain the climates felt on land, Moon told ABC News in 2021.

“What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic,” added climate scientist Jessica Moerman, currently vice president of science and policy at the Evangelical Environmental Network.

The jet stream, a band of strong winds moving west to east created by cold air meeting warmer air, helps to regulate weather around the globe. But as temperatures in the Arctic warm, the jet stream, which is fueled by the temperature differences, weakens, Moerman said.

Rather than a steady stream of winds, the jet stream has become more “wavy,” allowing very warm temperatures to extend usually far into the Arctic and very cold temperatures further south than usual, Moon of NSIDC added.

“These cold air outbreaks are really severe,” said Moerman. A study published in ‘Science’ found that the variability in the Arctic climate, specifically the weakening of the polar vortex, which keeps cold air closer to the poles, likely led to the Texas freeze in February 2022.

The same phenomenon is thought to be responsible for lashing the United States with powerful winter storms in mid-February 2023.

Conclusion

Climate change is happening more rapidly than anyone predicted even five years ago. Debate continues over whether the effects are natural or human-caused but there is no denying the evidence, which is all around us in the form of record-breaking heat waves, ferocious wildfires, more frequent and severe storms, melting glaciers and sea ice, and rising sea levels.

The disappearance of Arctic sea ice is disrupting the polar vortex, allowing cold blasts of air to extend as far south as Texas, bringing freezing temperatures and piles of snow.

Antarctica’s melting sea ice could slow down the current in the deepest parts of the ocean by 40% in three decades. This could alter the world’s climate for centuries and accelerate rising sea levels.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation has weakened over the past 150 years by approximately 15-20% due to the influx of freshwater from melted ice entering the system.

The last time the AMOC collapsed was during the late 1300s to 1400s, which overlapped with the Little Ice Age, when vast amounts of ice were flushed out into the North Atlantic, cooling its waters and diluting their saltiness, ultimately triggering a substantial global cooling.

What if AMOC keeps slowing down? Could it trigger another ice age? That would be quite a curve ball thrown to global warming crusaders.

Warmer- or colder-than-average ocean temperatures also have a direct effect on climate, as shown by the El Nino and La Nina weather patterns. We have just ended three years of La Nina and will soon be entering El Nino, which means that areas in the northern US and Canada will be dryer and warmer than usual.

In Western Canada, parts of BC, Alberta and Saskatchewan have been experiencing drought conditions since March. As of this writing, there were 98 active wildfires burning in Alberta, and 62 in British Columbia. Nearly 30,000 Canadians have been forced to flee their homes. As the map below shows, part of the Northwest Territories, Newfoundland/Labrador, and pockets of the Maritimes, are depicted as abnormally dry in yellow. A few areas mostly in Alberta are categorized as severe drought in brown.

In southern BC, the danger is not from too little water but too much. Among the towns worst hit by flooding, are Cache Creek and Grand Forks.

Evacuation orders or alerts are in place for several regional districts in the southcentral and southeastern parts of the province.

The flooding situation is likely to get worse towards the end of week, when the temperature will rise to 30+ degrees in some areas, causing more snow to melt and rivers to swell.

There is plenty of bad news regarding climate change and its effects on weather. The good news is we now have quite a good understanding of what causes droughts, floods, extreme heat, etc. This can assist businesses and individuals to better plan for disasters (because let’s face it, the government isn’t going to help you), and for market participants to better invest in the commodities that are most affected by weather and climate, such as crops and metals.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.