EV affordability confronted by rising component costs

2022.04.02

High fuel prices may have a lot of motorists thinking about how much longer they’re willing to drive their gas-guzzling clunker, but that might not mean very many will be heading to their nearest car dealership to purchase an electric vehicle.

That’s because EV prices are also rising on the back of higher component costs, especially for battery metals and copper, causing potential buyers to second-guess downshifting into green technology.

The inspiration for writing this article was a piece on Zero Hedge titled, ‘Morgan Stanley Fears Soaring Lithium Prices Could Spark Demand Destruction for EVs’.

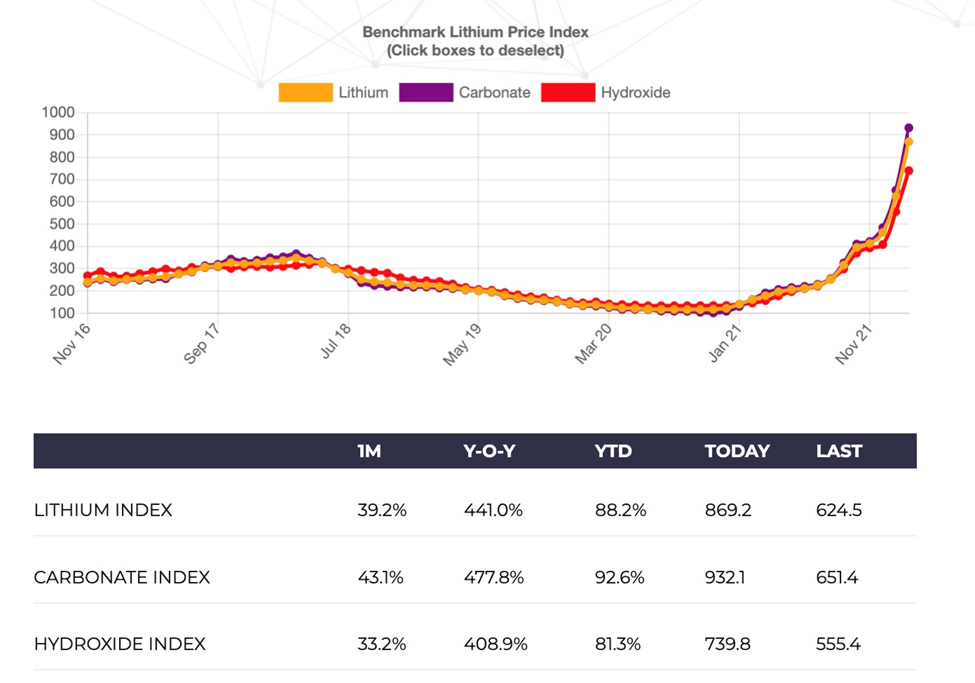

The investment bank warns that demand destruction is possible if electric vehicle prices increase too much in response to soaring commodity prices. Zero Hedge quotes Morgan Stanley telling clients that the cost of lithium carbonate has jumped fivefold over the past year, to around $74,000 per ton. The raw material cost increase has EV manufacturers set to raise vehicle prices by up to 15% — reversing a trend of declining battery costs over the past few years and hurting demand as the cost of “going green” gets more expensive.

That got me thinking, if the price of lithium is reflected in higher EV prices, what about all the other commodities that are in an electric vehicle? Lithium is only one component of a lithium-ion battery. There’s also nickel, graphite, and cobalt. The prices of all these commodities have risen significantly. Nickel and lithium’s unbelievable one-year gains, a respective 118% and 441%, make the 47% rise in retail gas prices, year over year, seem quite modest.

And then there’s copper. Electrification/ decarbonization literally does not happen without the red metal, which is heading towards a multi-year structural supply deficit as early as 2025. Copper prices have more than doubled in the past two years and there is a lot more copper in an EV than any of the above-mentioned metals. It’s in the motor, the wiring, and the charging stations. It’s also in the smart grid to get renewable energy to where it’s needed.

Let’s take a closer look at the prices of EVs and the raw materials that go into them.

EV sticker shock

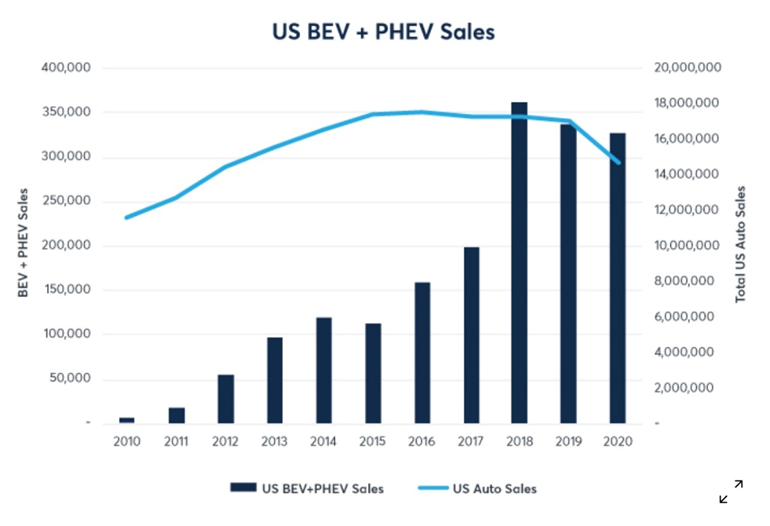

Even before the war in Ukraine hiked the prices of nickel and palladium, automobile metals produced in high volumes by Russia, electric vehicle prices were climbing. According to the Kelley Blue Book, at the end of 2021 EVs cost an average US$56,437, about $10,000 higher than the industry average of $46,329, which includes gas models and EVs.

And that’s if you can find one to buy. Both EVs and hybrids are in short supply largely due to the global microchip shortage. Bloomberg says while there now are far more models to choose from than previously, those that are available are scarce and expensive. For example the only electric pickup trucks currently in showrooms are Rivian Automotive’s R1T which starts at $67,500 and GM’s even pricier GMC Hummer.

Tesla reportedly raised prices twice this month in response to commodity price increases (they apply to Model Ss, 3s, Xs and Ys sold in the US, Canada, Australia and China), and also bumped up the price of its megapack battery that provides grid-scale energy storage.

Ditto for Rivian, which earlier this month hiked the sticker on its R1T pickup by 17% and R1S SUV by 20%.

The price of a Tesla Model 3 in Canada now starts at CAD$61,380 for the RWD version, making it ineligible for rebates in Quebec because the price exceeds $60,000. The Model 3 Long Range has been increased to $71,900 and the Performance Model now costs $81,490.

The higher-end Model Y is now $4,000 more expensive at $82,990, with the Performance version selling for $89,290, also $4K higher.

It’s not just Tesla and Rivian that are electing to pass on higher material costs to their customers. CNBC reported last week that a slew of electric car companies in China are doing the same.

Warren Buffett-backed BYD, start-up Xpeng, WM Motors, and SAIC-GM Wuling, the joint venture between General Motors and Chinese state-owned SAIC, have all increased prices.

In fact, new vehicle inflation is pressuring some electric carmakers to make an uncomfortable choice: either absorb a lower margin, or scrap less-profitable models. CNBC reports that Ora, an electric car brand under China’s Great Wall Motors, has already suspended orders for two of its models. The company said its Black Cat car was losing 10,000 yuan ($1,569) per unit as a result of the rising raw material costs.

“Expect a shake down of some form which will eliminate some of the weaker mid-to-entry level priced products,” Bill Russo, CEO at Shanghai-based Automobility Limited, told CNBC. Analysts say Tesla and BYD are better positioned to weather rising prices due to their strong supply chains.

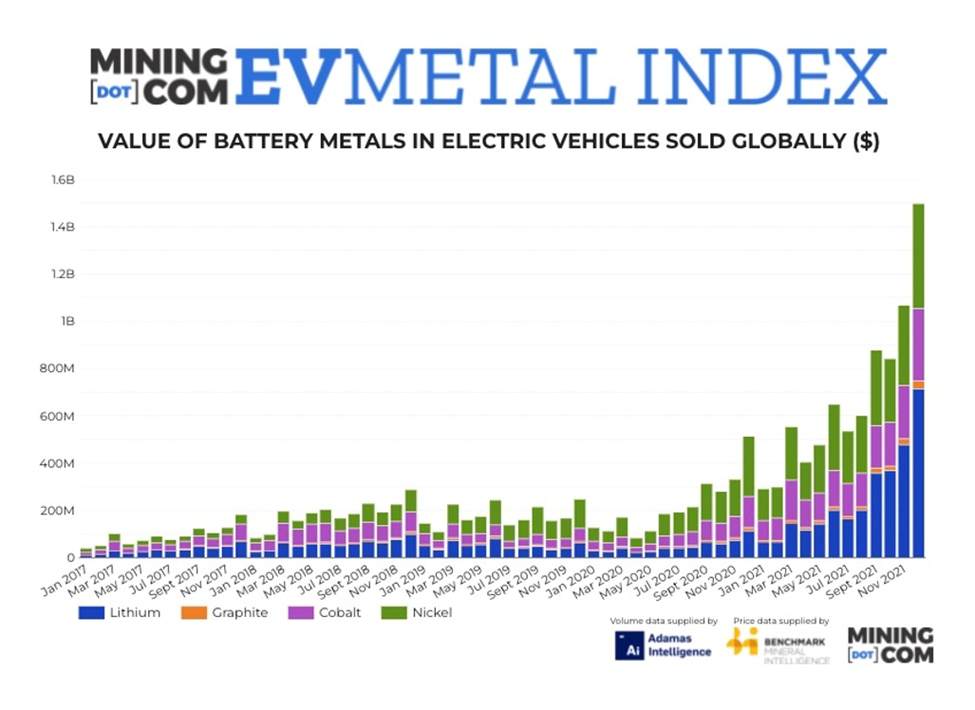

EV Metal Index soars

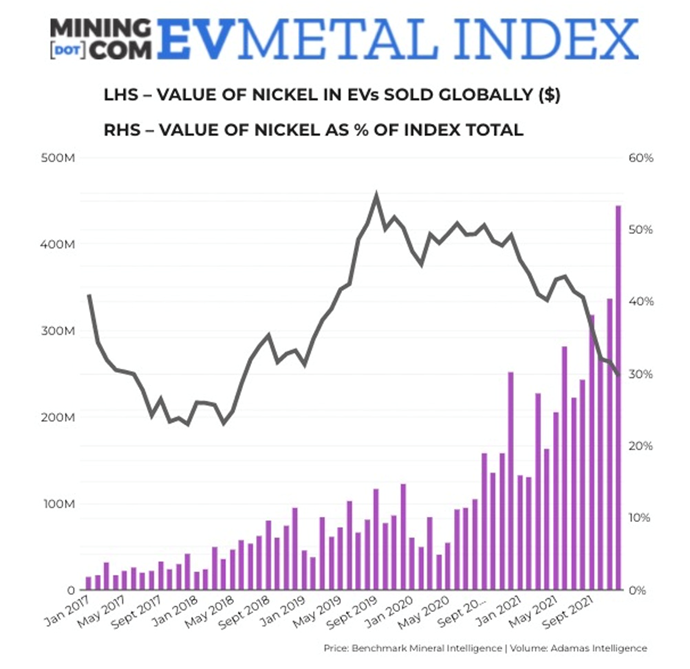

The extent to which material costs are impacting EV prices is strikingly evident by the EV Metal Index, a collaboration between Adamas Intelligence, Benchmark Minerals Intelligence and Mining.com. Again, we saw this trend locked in several months before the war in Ukraine.

In December the index, which tracks the value of battery metals in newly registered passenger EVs and hybrids, totaled $1.5 billion, an increase of 192% over December 2020.

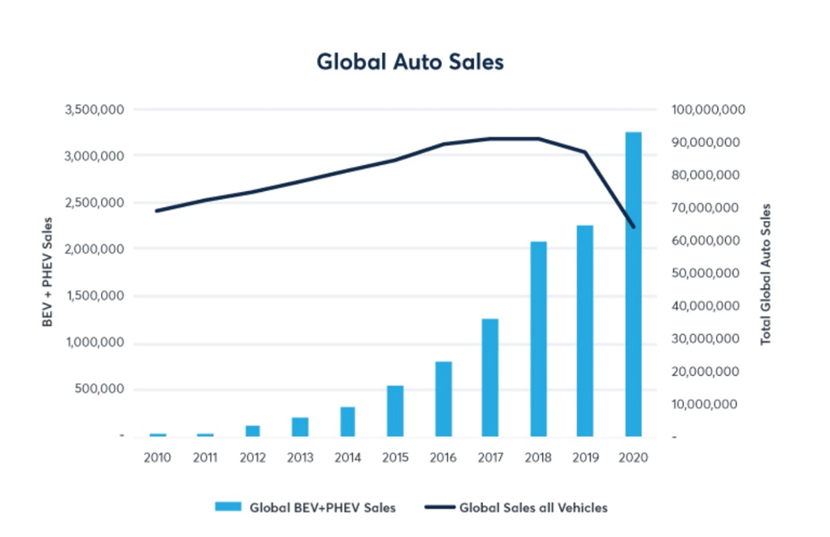

Annual EV sales in 2021 surged to over 10 million units, with full electrics accounting for 49% of the total and plug-in hybrids 19%.

Raw material costs

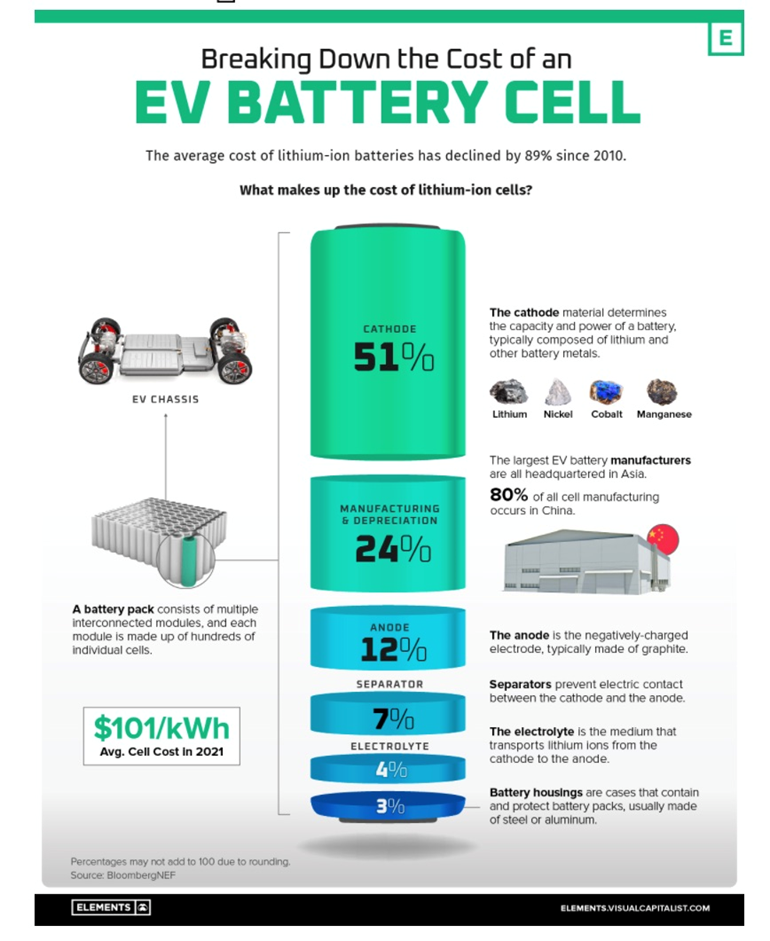

The battery pack is the most expensive part of an electric vehicle, accounting for about 30% of its sticker price. The priciest component of each lithium-ion battery cell is the cathode, containing a mix of lithium and other battery metals, typically nickel, cobalt, manganese and aluminum. The reason these metals are so expensive is they need to be mined, processed and converted into high-purity chemical compounds.

According to Visual Capitalist, since 2010 the average price of a lithium-ion EV battery pack has fallen from $1,200 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) to $132/kWh in 2021. However, even with this dramatic price reduction, it’s still above the $100/kWh threshold where the cost of an electric vehicle matches that of an internal combustion engine model. Experts say until that happens, EV prices will be too expensive for mass adoption.

Lithium goes bonkers

Unfortunately for battery makers, auto manufacturers and car buyers the trend of falling battery costs has come to an abrupt halt with the widespread increase in commodity prices.

The price of lithium is up more than 400% year on year, and nickel prices have soared owing to the war between Ukraine and Russia, a major supplier of the base metal through state-owned miner Norilsk.

In China, the largest market for electric vehicles, lithium carbonate prices remain elevated in 2022 after quadrupling in value last year. According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence’s mid-February price update, battery-grade lithium carbonate in China was selling for around $60,000 per tonne, double Europe’s carbonate prices of $30,000/t.

Not only have lithium prices gone bonkers, the amount of the battery ingredient per EV has increased.

In December 2021 a record 25,900 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) were deployed on global roads in batteries of all newly sold passenger EVs, 68% more than the previous December, Adamas Intelligence reported.

Average lithium on a per vehicle basis was up 12% year over year in December, from 18.5 to 20.7 kg.

“The price explosion tells you that lithium supply is simply nowhere near enough to feed this demand surge,” OilPrice.com reported recently.

According to research by Fastmarkets, the lithium market is facing a growing deficit through 2023, with a deficit of 60,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) in 2022 and a deficit of 89,000 tonnes of LCE in 2023.

The commodity price reporting agency quotes William Adams, Fastmarkets’ head of battery metals research, stating that lithium has further room for price growth due to its bullish market fundamentals:

“Given that it takes five to ten years to build a new lithium operation but one to two years to build a new manufacturing plant, and EVs are expected to have a compound annual growth of 20-plus percent, producers are going to really struggle to bring enough material on board — unless demand slows,” Adams said.

Nickel breaks the exchange

Battery metals nickel and cobalt were already facing tight supplies this year before the war in Ukraine made nickel go “parabolic”. On March 8, nickel trading was suspended in London after prices more than doubled. Activity on the London Metal Exchange (LME) was so frenzied, the 145-year-old bourse had to cancel trading after an unprecedented price spike saw brokers struggling to pay margin calls against unprofitable short positions.

The base metal used in stainless steel and electric-vehicle batteries surged more than 250% in two days, briefly hitting $100,000 a ton, as investors and industrial users who had sold nickel scrambled to buy the contracts back after prices rallied.

The largest-ever price move on the LME began shortly after the US considered banning Russian crude oil imports. (a day later, Europe and the US announced bans) This sparked a massive squeeze in commodity markets, including oil, gas, nickel, aluminum and palladium. All hit multi-year highs or new record highs, according to Bloomberg.

Nickel’s vertical price spike is seen in Kitco’s graph below.

CNBC reported the price surge could undermine ambitious EV rollout plans by global automakers including GM and Ford.

Nickel is especially important to an EV battery because it boosts a battery’s energy density, thereby giving more range per pound of batteries. Older lithium-ion batteries had about one-third nickel in their cathodes, compared to new batteries containing at least 60% Ni.

Like lithium, the increased uptake in nickel use is raising concerns over nickel supply. According to CNBC, Analysts at Rystad Energy warned last fall that global demand for the high-grade nickel required for EV batteries is likely to outstrip supply by 2024, a message that has since been echoed by other commodity analysts, including Jonas’s counterparts at Morgan Stanley.

Nickel use in EV batteries was up 44% in December compared to a year earlier, hitting a new record of 19,600 tonnes, or 15.7 kg per vehicle, according to above-cited EV Metal Index.

Cobalt use dropping

Battery makers and EV companies are substituting high-nickel battery chemistries for cobalt because cobalt is more expensive. Despite cobalt deployment rising 36% in December to over 4,000 tonnes for the first time, on a per vehicle basis the metal’s usage has dropped 10%.

According to McKinsey, a typical EV with an NMC622 55 kWh battery pack will contain 7.4 kg LCE and 12 kg of refined cobalt. A similar car in the future with a 77 kWh battery pack equipped with a NMC811 cathode will contain 8.4 kg LCE and 6.6 kg of refined cobalt.

Cobalt hydroxide topped $65,000 per tonne in January, its highest price since 2018.

Graphite following lithium higher

Graphite is the only material that can be used in a lithium-ion battery anode, there are no substitutes. This is due to the fact that, with high natural strength and stiffness, graphite is an excellent conductor of heat and electricity. Being the only other natural form of carbon besides diamonds, it is also stable over a wide range of temperatures.

In this regard, graphite is indispensable to the global shift towards electric vehicles. It is also the largest component in lithium-ion batteries by weight, with each battery containing 20-30% graphite. But due to losses in the manufacturing process, it actually takes 30 times more graphite than lithium to make the batteries.

According to the World Bank, graphite accounts for nearly 53.8% of the mineral demand in batteries, the most of any. Lithium, despite being a staple across all batteries, accounts for only 4% of total demand.

The anode material, called spherical graphite, is manufactured from either flake graphite concentrates produced by graphite mines, or from synthetic/artificial graphite. Only flake graphite upgraded to 99.95% purity can be used.

An electric car contains more than 200 pounds (>90 kg) of coated spherical graphite (CSG), meaning it takes 10 to 15 times more graphite than lithium to make a Li-ion battery.

Naturally, this has meant higher graphite deployment in EV batteries globally. The EV Metal Index in December recorded a 78% jump, year on year, to just under 39,000 tonnes of synthetic and natural graphite, a new record. Graphite usage per vehicle was up 19% to 31 kg.

From December 2020 to December 2021, graphite prices rose 20% to roughly $680 a tonne, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence data, after spending most of 2020 below $700/t.

Copper in EVs

Finally we come to copper, the great unsung hero when it comes to the electrification of the global transportation system. While most eyes are on the battery metals lithium, graphite, nickel and cobalt, the role played by copper cannot, and should not, be underestimated. Not only is copper used extensively in electric vehicle production, it is also intrinsic in the various elements of EV infrastructure, i.e. charging stations and power cables used in underground power transmission.

As I stated at the top, without copper, there is no gasoline/ diesel to EV shift.

According to Visual Capitalist, compared to silver and gold, copper is by far the cheapest option for electrical wire. Moreover, copper is nearly as conductive as silver, the most conductive metal, but it comes at a fraction of the cost.

An electric vehicle contains about four times as much copper as a traditional ICE-powered car or truck. The main reason for this is the electric motor, made from copper, steel and permanent magnets containing rare earths. An electric motor may have over a mile of copper wiring. According to Copper.org, while conventional gas cars contain 18 to 49 pounds of copper, an EV contains 183 pounds, or 83 kilograms.

The amount of copper needed for EVs is expected to increase by 1.7 million tonnes by 2027, an amount just shy of China’s 1.8Mt of copper production in 2021.

An article last year by CME Group provided another dramatic projection for how much copper will be needed for future EV growth. Based on global sales of 3.2 million battery-electric (BEVs) and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) in 2020 — representing just 5% of total auto sales — CME says that this amount of EVs would require an additional 345 million pounds of copper, where a PHEV contains 132 lbs and a BEV has 183 lbs.

That works out to 156,489 tonnes. According to the US Geological Survey, that is only 13% of US copper production in 2021. Do-able, right? However, BloombergNEF is forecasting global EV sales to pass 54 million units by 2040, representing more than 50% of total auto sales.

The amount of copper this would require amounts to 2,640,751t — equivalent to the entire production of Peru, the second largest copper producer behind Chile, and Poland, home to the Kupferschiefer copper deposits that are the largest source of copper in Europe and the world’s largest accumulation of silver on the planet.

And we haven’t yet accounted for the amount of copper required by charging stations. While the charger itself doesn’t contain a lot of copper, the wires connecting the charger to the electrical panel as well as the charging cable itself are the main sources. Wood Mackenzie estimates there will be over 20 million charging points globally by 2030, consuming 250% more copper than in 2019.

A low-powered charging station (3.3 kW) has 0.7 kg of of copper, while a high-powered charging station (200 kW) contains 8 kg. Read about the three types of charging stations

Whether or not the mining industry can produce enough copper for electric vehicles and EV infrastructure, along with all the other uses of copper that are expected to remain in high demand, such as construction, telecommunications and transportation, is a very open question right now.

Copper’s structural supply deficit

Copper hit a new record high on May 4, with futures briefly touching $4.94 per pound, as traders stocked up over concerns about supply disruption, along with historically low global stockpiles.

Of course, the big story for copper is tight supply.

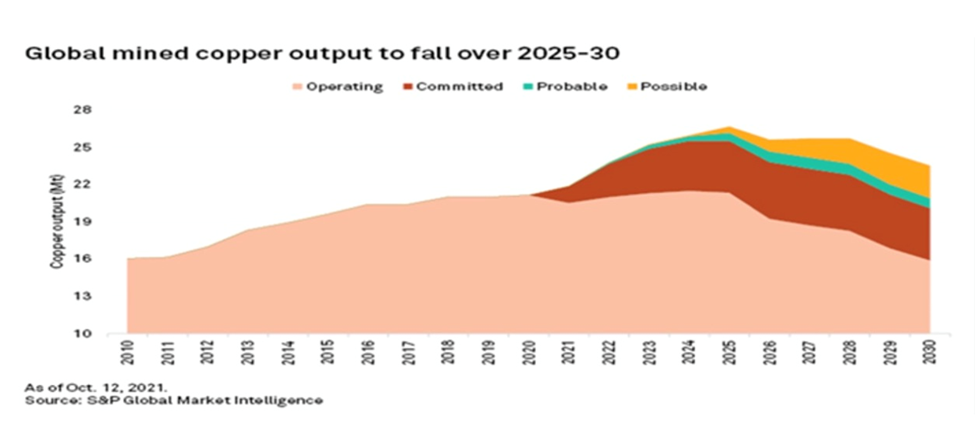

Diminishing supply from currently operating mines, combined with the projected increase in demand for copper concentrate over 2021-2030, could result in a 3.85Mt production shortfall in 2025, according to S&P Global estimates.

BloombergNEF projects that in 20 years, the world’s copper miners must double the amount of global production — from the current 20 million tonnes annually to 40 million tonnes — just to match the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles.

This is a tough ask considering some of the world’s largest mines are seeing depleted copper reserves and lower ore grades, so it would be difficult for global production to even maintain a 20-million-tonne-per-year pace.

CRU estimates that without new capital investments, global copper mined production will drop below 12 million tonnes in 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15 million tonnes.

“Goldman analyst Nicholas Snowdon told a copper conference Wednesday that current near-record prices need to go much higher in order to stimulate a supply response. The next day, Freeport boss Richard Adkerson said market tightness “is far beyond a price issue.”

So while copper companies like Freeport, the top publicly trader producer, are raking in the cash, there’s not much they can do to significantly accelerate projects given a deterioration of deposit quality and more demanding operating environments, Adkerson said in an interview. That’s a problem, with copper demand set to surge in the clean energy transition.

Even if the price of copper were to double overnight it would still be years before we had significant incremental production coming on,” he said. The market is going to need it far faster than companies like ours can produce it.” Copper tightness is far beyond a price issue, Mining.com

To avoid a global copper crisis heading into the latter half of this decade, the mining industry has to step up its efforts in making new, significant discoveries. According to CRU, the industry needs to spend upwards of $100 billion to erase what it estimates to be a 4.7Mt deficit by 2030.

Reaping the rewards of this investment will be the junior miners, especially those with copper projects capable of matching the production of some of the world’s best deposits.

Max Resource Corp.

At AOTH we believe Max Resource Corp’s (TSXV:MAX; OTC:MXROF; Frankfurt:M1D2) CESAR property has real potential to be one of the largest copper-silver systems ever discovered.

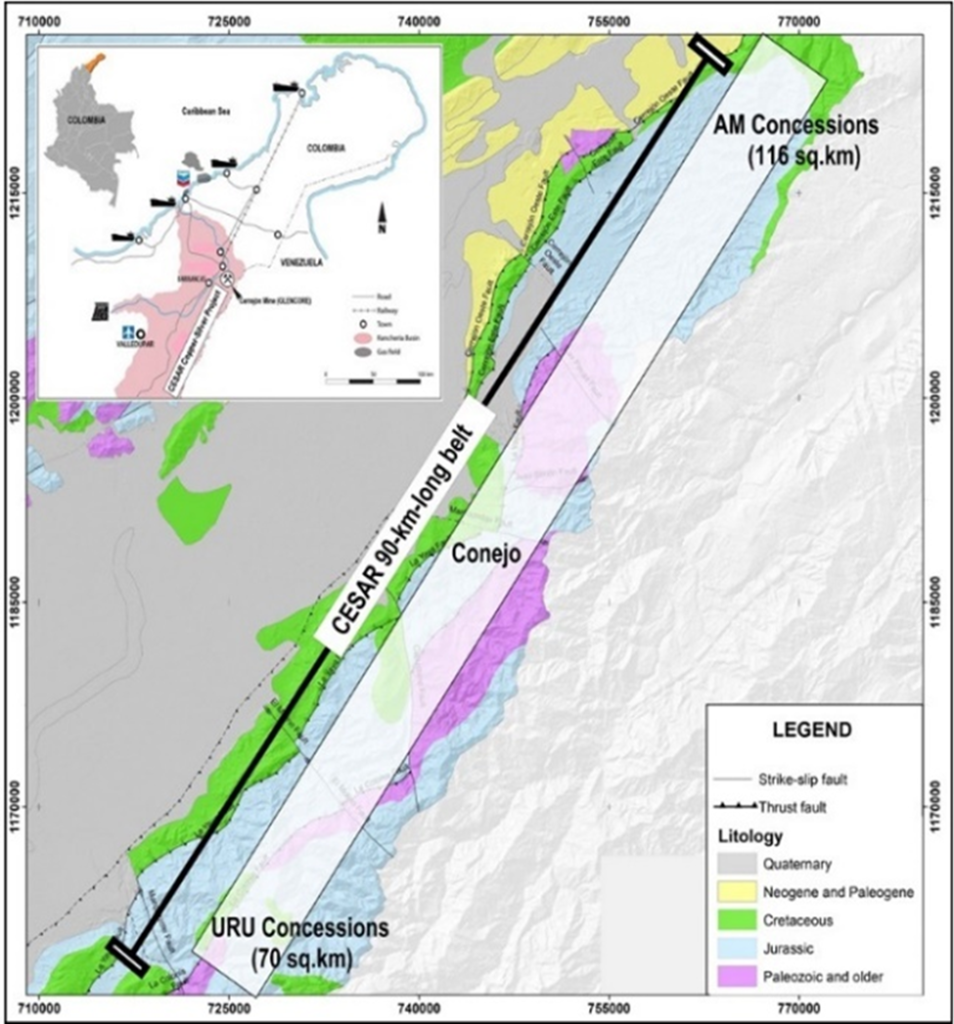

This district-scale project is situated along the Andean Copper Belt, the world’s leading copper-producing area, within a region that enjoys major infrastructure from existing mining operations including Cerrejon, the largest open-pit coal mine in South America. (see map below).

This includes roads, railways, hydroelectric power, and nearby port facilities from where coal is already being shipped.

The entire project area lies on a massive sedimentary system covering a significant portion of the 200 km long Cesar Basin, a geological feature that extends for over 1,000 km from the northern tip of Colombia southwards through Ecuador and Peru.

For over the past two years, Max has not only been discovering high-grade copper zones on its flagship CESAR property but is expanding these areas moving ever closer and closer to confirming the existence of a massive sediment-hosted system.

Max has, so far, received 19 mining concessions covering a total area of 186 km² (additional concessions are pending). This is more than any other company has ever received in Colombia.

On Feb. 28 Max Resource announced a transaction with Endeavour Silver Corp (TSX:EDR) whereby Endeavour bought 5% of Max through a private placement totaling CAD$7.7 million. It is expected that all permits and concession rights will be approved in advance of a June drill program.

The Cesar Basin, estimated to extend for 90 kilometers, hosts three discoveries: URU, AM and Conejo. The area of approved concessions exceeds 70 square km at URU and 116 km² at AM. In other words, this is a huge property.

Discovery zones along the CESAR North 90 km copper-silver belt

Conclusion

The incentive for discovering and permitting new copper mines has never been greater.

The prospect of running out of copper before the gasoline to EV transition is complete is particularly alarming, given how intensive copper usage is in EVs compared to the other metals.

Consider: An average EV contains 20.7 kg of lithium, 15.7 kg of nickel, 12 kg of cobalt and 31 kg of graphite. Copper usage per EV is 83 kg. That is more than twice the graphite, nearly 7 times the cobalt, over five times the nickel and four times the lithium. While battery metals will be challenged to meet the required demand, their supply problems pale in comparison to copper’s, simply due to the amounts required per EV and per charging station – let alone all the new copper supply needed for building a smart electrical grid and for 5G and global infrastructure plans.

Copper has doubled in two years. With a nearly 4Mt shortfall predicted as soon as 2025, it doesn’t sound unreasonable for it to double again. For now, EV makers aren’t concerned about having enough copper around. In three years, they will be scrambling. As we’ve stated before, the hurtling freight train of copper demand is about to slam into the immovable object of diminished supply.

As far as AOTH is concerned, Max has everything we like to see in a junior mining company i.e. good jurisdiction, infrastructure, quality management, scalability, in-demand metals, high grades, and to top it all off, a recent deal with a mid-tier miner adding the deep-pocketed financial capability the Colombian government wanted to see.

The shares are tightly held by management (12%), high net worth individuals (38%), institutions (18%) and retail (24%), with a float of just 130,890,992 shares outstanding, and that is after the $7.7M financing.

The CESAR project is in a great mining location with plenty of existing infrastructure thanks to its proximity to Glencore’s Cerrejon coal mine and associated rail, road, power and port facilities.

A recent poll shows the number of Colombians who believe mining has a positive impact on the country’s economy continues to increase. According to the report by the National Association of Colombian Entrepreneurs, 74% of residents in municipalities where there are mining operations, and 64% of those living in non-mining towns, believe that mining benefits Colombia. This includes the northern Cesar region where Max is developing its project.

In the most recent (2020) Fraser Institute survey of mining companies, Colombia was ranked first among Latin American nations for investment attractiveness, ahead of Chile, Peru, Brazil and Mexico. As a testament to the country’s stability, among the major mining companies working in Colombia presently are BHP, Barrick, Newmont, Anglo American, Yamana, Glencore and Agnico Eagle.

Max’s CESAR discovery lies on the northern edge of the Andean Copper Belt, host to some of the largest and richest copper deposits in the world.

The property has geological similarities to both Poland’s world-class Kupferschiefer deposits and the Central African Copper Belt, which hosts Ivanhoe’s Kamoa-Kakula discovery — the world’s biggest copper project with nearly 38Mt of contained metal.

Kupferschiefer is Europe’s largest copper mine, with production in 2018 of 30 million tonnes grading 1.49% copper and 48.6 grams per ton silver from a mineralized zone of 0.5 to 5.5 metre thickness.

Kupferschiefer is also the world’s leading silver producer, yielding 40 million ounces in 2019, almost twice the production of the world’s second largest silver mine (World Silver Survey 2020).

Owning Max gives investors tremendous upside leverage to a discovery. The initial drill program at URU, expected to begin this month, is at a target where surface sampling featured values up to 14.8% copper and 132 g/t silver, hosted in an “African Belt”-style mineralized envelope. The zone’s large-scale potential was confirmed in December when as many as five drill target zones over 15 km of strike, with widths of 5 to 25 meters over 500 vertical meters, were identified by the Max team.

Drill targets are also being delineated at the Conejo and AM targets to the north. The AM discovery features Kupferschiefer-type mineralization with highlight values of 34.4% copper and 305 g/t silver. Conejo has high-grade copper-silver over 3.7 km, averaging 4.9% Cu (2% cutoff) and open in all directions.

In sum, Max Resource is exploring for copper and silver, two “in-demand” metals for the green economy, at the right time, in a mining-friendly jurisdiction with plenty of existing infrastructure. Exploration to date has demonstrated that CESAR has both the potential size and grades for a multi-decade copper operation.

The company’s field team features Dr. Chris Grainger, a consulting geologist with expertise in Colombia, Piotr Lutynski, described as a “Kupferschiefer-style” geologist, and Dr. Adam Pietrzynski who hails from Krakow, Poland, giving credence to the geological model being advanced at the AM discovery.

What’s really enticing about this project is its extremely unique geological model and the high probability of building out a large resource. Unlike a porphyry deposit, where you have a huge bulk tonnage of low-grade material, the mineralization at CESAR is blanketed in nature and it has extensive lateral continuity. As seen with the Kupferschiefer system, it can be thousands of square kilometers.

“There’s only three to five of these things in the world, and the ones that have proven to be productive, and find critical mass, that have gone to production or are going to production, are literally some of the largest deposits in the world,” Brad Aelicks of Pyfera Capital recently told us in an interview.

“You find one of these things, the value isn’t can we find enough tonnage for a 10-year mining operation, which is kind of the minimum threshold out there, you’re looking at, if you find one of these things that Max is working on, which is a sediment-hosted copper-silver deposit, you’re looking at mine life potential of a hundred years,” he added.

In our opinion, Max ticks all the boxes required to make it a must-own going into April.

Max Resource Corp.

TSXV:MAX; OTC:MXROF; Frankfurt:M1D2

Cdn$0.57 2022.04.01

Shares Outstanding 130.8m

Market cap Cdn$72.9m

MXR website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Richard owns shares of Max Resource Corp. (TSXV:MAX). MAX is a paid advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.