2022.06.09

Last month, we reported that Tesla, the largest electric vehicle manufacturer, was removed from the S&P 500 ESG Index, due to claims of racial discrimination and crashes linked to its automated vehicles. The removal from the database caused Tesla’s hot-headed CEO, Elon Musk, to tweet, “ESG is a scam. It has been weaponized by phony social justice warriors”.

Others were equally perplexed as to how Tesla, whose mission is to “accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy” could fail to make the cut. The decision to exclude it has raised new questions about what ESG actually means, including one by Bloomberg, who asked, If Tesla isn’t good enough for an ESG index, then who is?

Factors that led to Tesla’s departure from the index include the company’s failure to publish details of its low-carbon strategy or business conduct codes, Reuters reports. In February a California state agency sued the automaker over allegations by black workers that it tolerated racial discrimination at an assembly plant.

Mining and ESG

As far as mining, ESG is no longer a “nice to have”, but instead, needs to be accounted for up-front by mining companies in their corporate presentations, media releases and other public documents.

According to a recent study published by Ernst & Young (EY), losing social support, or social license to operate (SOL) is now seen as the main risk mining firms are facing.

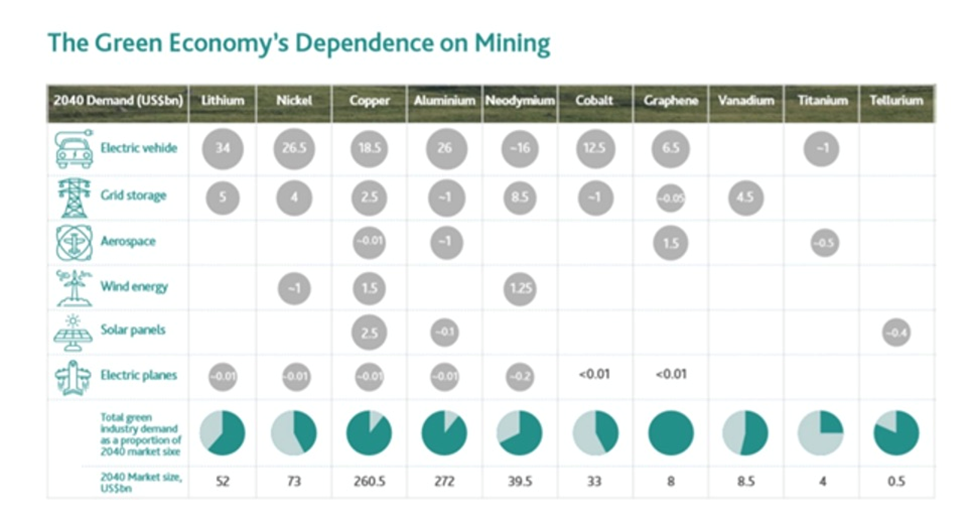

Another survey by BDO said stakeholders are demanding stronger engagement, transparency, and accountability, to the point where a social license will soon be akin to a mining permit. More positively, attaining a social license will shine a light on the industry’s importance in providing the raw materials for the future green economy.

“To meet the aspirations of consumers, mining is essential in the making of communications devices, consumer electronics and food production. Social license is the key to unlocking these positive mining outcomes,” says Sherif Andrawes, BDO’s global head of natural resources. “People see phones, cars, TVs but the link back to mining is often not made.”

Of course, with greater transparency, mining companies will increasingly be called upon to address climate change by reducing their carbon footprints.

One of the most important KPIs for sustainable mining is procurement of local supplies.

Stakeholders want to see concrete results that mining activity is benefiting the host country’s economy.

In January 2021, Mining Shared Value (MSV), a non-profit initiative of Engineers Without Borders, announced that four mining firms, including Ivanhoe Mines and Lundin Gold, have adopted the Mining Local Procurement Reporting Mechanism (MLPRM).

The MLPRM contains a set of disclosures for companies to provide information on, such as local procurement policies, how much is spent in host countries, and supplier programs. It is also designed to meet the requirements of other standards, such as the World Gold Council’s Responsible Gold Mining Principles and the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance standard.

More evidence of the growing importance of ESG in mining comes from a survey, conducted during the second half of 2020, of 67 decision-makers by global law firm White & Case.

Eighty percent of respondents think ESG will play a greater part in investors’ decision-making in the 2020s, and 14% expect ESG will lure generalist investors to allocate capital to the sector. Twenty two percent see ESG as a way to build greater resilience in future, second only to supply chain excellence.

The DRC

With ESG taking on a higher profile in mining, I was curious to see a Bloomberg story this week highlighting the potential for the DRC to become part of the so-called green-energy transition.

If Tesla gets kicked off the S&P 500 ESG Index, for relatively minor transgressions, in my opinion so should any company working in the Congo, an economic and political basket-case of the highest degree.

According to Africa Mining, among the mining firms active in the country, are such familiar names as AngloGold Ashanti, Freeport McMoRan, Glencore Xstrata, Ivanhoe Mines, and Randgold Resources.

Ivanhoe, for one, last year reached commercial production at its massive Kamoa-Kakula copper project, 100% of which, incidentally, will go to China during the mine’s first phase.

Heavily quoting the DRC’s director of mining registry, Jean Felix Mupande, the article states about 500 mining permits are in advanced development and will soon lead to new projects for lithium and cobalt — battery metals driving the shift to electrification — while mines for copper, tin, tantalum and tungsten will also be built.

Interest in Congolese mining is clearly being driven by higher metal prices, despite the country’s sordid reputation for human-rights abuses and illicit trade in conflict minerals. Not only does the Congo have zero environmental standards, it routinely uses child labor in its dirty and dangerous mines.

The DRC holds two major distinctions. First, it is the richest country in the world in terms of mineral wealth, at an estimated $24 trillion.

Second, it is the country in which the highest number of people — estimates go as high as 10 million — have died due to war since World War II.

The Congo’s staggering economic potential (the DRC contains 5% of the world’s copper and 50% of its cobalt) is matched only by its poverty and corrupt mismanagement.

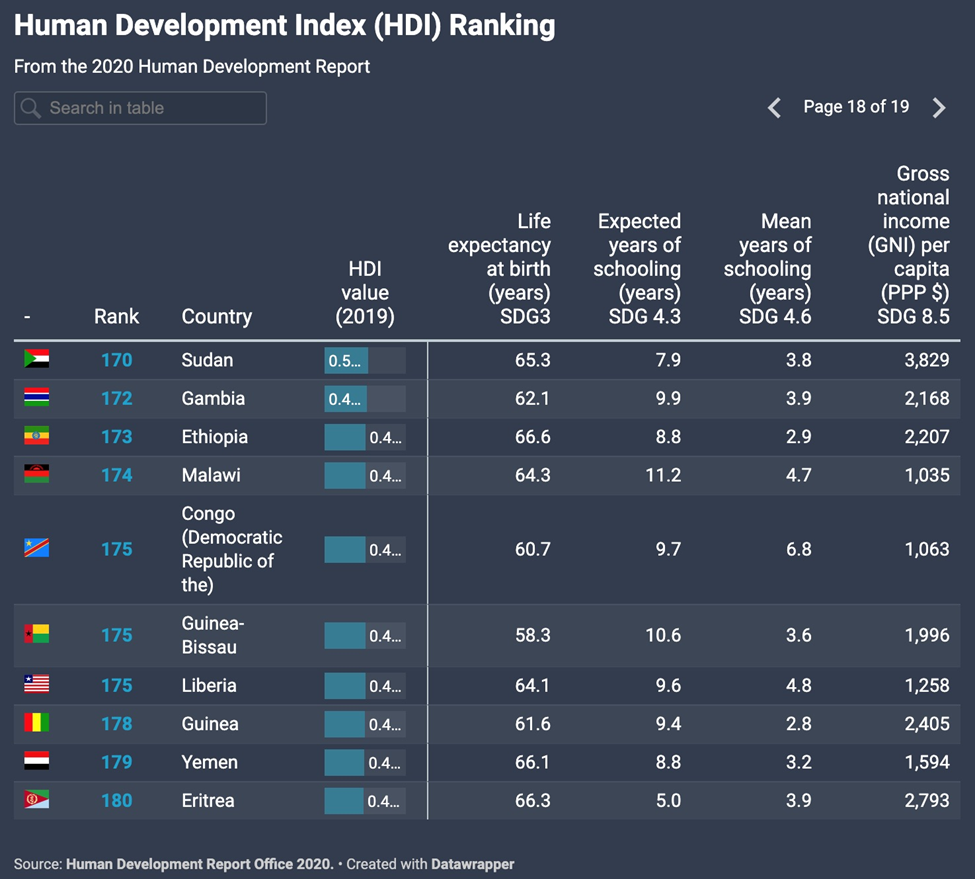

The Democratic Republic of Congo ranks 175th out of 189 countries in the UN Human Development Index (HDI) rankings, which represent an annual assessment of measures of progress in human well-being. Countries at the bottom of the list suffer from inadequate incomes, limited schooling opportunities and low life expectancy rates due to preventable diseases such as malaria and AIDS.

UN special representative Margot Wallstrom called the DRC “the rape capital of the world” and both government forces and the militias in control of various parts of the country practise it.

Although a peace agreement was signed in 2002, conflict has continued in many regions of the country. On May 22 Al Jazeera reported that violence has resumed in North Kivu province, where tens of thousands of people were forced to flee their homes. It’s the latest episode of what the Norwegian Refugee Council calls the world’s most neglected displacement crisis.

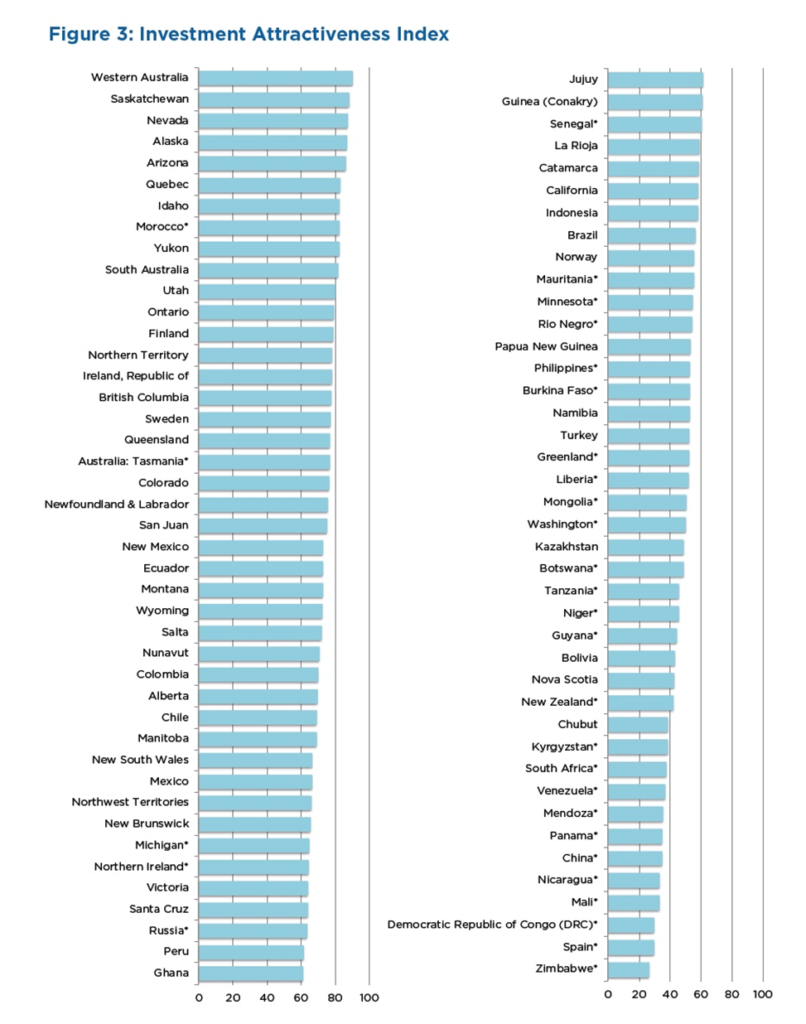

In terms of mining investment attractiveness, the DRC ranks third from last in the list of countries considered the best for mining companies to do business, according to the latest 2021 Fraser Institute rankings.

Another fairly recent study pointed to 34 countries that have seen a significant increase in resource nationalism. Countries now rated “extreme risk”, according to the March 2021 report by Verisk Maplecroft, include major African copper producers Zambia and the DRC.

The Congolese government in 2018 raised taxes on mining firms and increased royalties, and one year ago, slapped a ban on the export of copper and cobalt concentrates — an action almost identical to what has happened in Indonesia with nickel.

China

Of course, it isn’t only the DRC that any mining company giving a hoot about its reputation, and ESG credentials, ought to swerve.

Next on our list of countries with the worst environmental records viz a viz mining operations, and human rights, would be China.

In China’s Inner Mongolian city of Baotou, dozens of pipes churn out a torrent of thick black chemical waste that flows into an artificial lake filled with toxic sludge. A constant smell of sulfur pervades the apocalyptic scene. Most people in the West haven’t heard of Baotou but its mines and factories are one of the biggest suppliers of rare earth minerals used in a plethora of so-called green applications, everything from wind turbines to electric vehicles to nuclear reactors.

In the Jianxi region of southeastern China, the process of mining rare earths using a mix of water and chemicals, has caused extensive water and soil pollution. China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology estimates the cleanup bill for southern Jiangxi Province could amount to around $5.5 billion, with only a fraction of that spent as of July 2019, when this article was written.

How much mining takes place in the regions housing China’s beleaguered minority groups? We can’t say but according to Human Rights Watch, The Chinese authorities are committing crimes against humanity against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang. Abuses committed included mass arbitrary detention, torture, enforced disappearances, mass surveillance, cultural and religious persecution, separation of families, forced returns to China, forced labor, and sexual violence and violations of reproductive rights…

Authorities in Tibetan areas continue to severely restrict freedoms of religion, expression, movement, and assembly. They also fail to address popular concerns about mining and land grabs by local officials, which often involve intimidation and unlawful use of force by security forces…

The ecological risks (air pollution, biodiversity loss, desertification/drought, crop damage, landscape/aesthetic degradation, soil contamination, soil erosion, waste overflow, deforestation, surface water pollution/decreasing water quality, groundwater pollution or depletion, mine tailings spills) of mining

aren’t confined to China, which cornered the REE market in 2010, and has since locked up global supplies & processing capabilities for nickel, cobalt, graphite and lithium.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, nickel is produced from laterite ores using the environmentally damaging HPAL technique. (HPAL stands for High Pressure Acid Leach). The advantage of HPAL is its ability to process low-grade nickel laterite ores, to recover nickel and cobalt. However, HPAL employs sulfuric acid, and it comes with the cost, environmental impact and hassle of disposing the magnesium sulfate effluent waste.

The Indonesian government only recently banned the practice of dumping tailings into the ocean (DST) for new smelting operations, but it isn’t yet a permanent ban.

Most of four HPAL plants currently under construction, led by Chinese stainless steel producers and battery makers, plan to continue the environmentally egregious practice of DST, due to the much higher cost of managing the tailings on land.

Not only that, the process of refining nickel to make nickel pig iron, and now, nickel matte, is highly energy-intensive (it relies on coal-fired power) and creates a lot of air pollution.

Producing 1 ton of nickel in nickel pig iron creates 45 tons of carbon dioxide emissions, compared to just 20 tons for coal-powered aluminum and steel production requiring an average 2 tons of CO2 per ton of metal.

Funny, isn’t it, that the S&P 500 ESG Index chose to remove Tesla from its index for supposed racial discrimination, when its real crime — an environmental one — is processing laterite nickel for its batteries.

In 2020 Tesla signed a contract with Vale-NC to supply intermediate mixed nickel and refined cobalt produced in New Caledonia. Nickel mined in the South Pacific French territory is laterite. The only way to process laterite nickel is through highly polluting HPAL.

Last month, company representatives flew to Indonesia to visit Morowali, the nickel production center on Sulawesi Island. This was followed by a visit from Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo to Tesla’s Gigafactory in Texas, to meet with Elon Musk.

Conclusion

After putting out the word that mining companies need to extract more nickel for EV batteries, Elon Musk made a deal for laterite nickel in New Caledonia. Processing this type of nickel creates about four times as much pollution as traditional nickel processing, from sulfide nickel deposits such as those found in Canada and the United States.

Two years later, Musk is at it again, banging on Indonesia’s door hoping to build a processing plant using, you guessed it, laterite nickel.

Tesla has been kicked off the S&P 500 ESG Index, for reasons other than mining nickel, yet Exxon Mobil is allowed to stay on the list.

The oil major knew about human-caused climate change for decades, but sowed doubts about the science behind it to prevent policies from being passed that would hurt the company’s bottom line.

Ivanhoe Mines pays lip service to buzzwords like “sustainability” and ESG, while doing business in the Congo, and shipping its copper & cobalt end products to China, another environmental laggard and human rights abuser, for processing.

Glencore is a major DRC miner that owns Mutanda, the largest cobalt mine in the world. Obviously not averse to operating in sketchy environments, US corruption and bribery cases against the company include allegations about the conduct of two former executives. The commodities giant has also plead guilty to rigging fuel-oil assessment prices.

When companies like this are allowed to stay on ESG indices (or aren’t called out) while higher-profile firms like Tesla are removed for comparably minor transgressions, it casts doubt on the legitimacy of the whole enterprise.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.