Electrification metals nickel, cobalt, palladium in play following Russian moves in Eastern Ukraine

2022.02.23

Weeks of failed diplomacy over a potential invasion of Ukraine resulted in Russia’s decision, over the weekend, to recognize the independence of two Russia-backed breakaway separatist areas in Eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region.

Vladimir Putin declared the self-proclaimed People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk independent, prompting sanctions from Western countries including the United States and Germany, which halted the approval of a major gas pipeline from Russia. (Putin’s timing was not coincidental, coming immediately following the conclusion of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, China, a Russian ally)

As Kyiv and its Western partners wait to see whether Russian forces entering Donetsk and Luhansk will try to break through Ukrainian positions, Germany reportedly put the under-construction Nord Stream 2 pipeline on hold. The threat of Moscow withholding gas supplies to Europe in retaliation saw EU gas futures surge 8%, to around €80 per megawatt-hour. The trading bloc has become increasingly reliant on Russian gas for electricity generation, industrial usage and home heating, importing over 80% in 2020 compared to 65% a decade earlier.

Meanwhile the EU imposed sanctions on members of Russia’s Duma (parliament), and agreed to a ban on the purchase of Russian government bonds.

The United States for several weeks has been threatening sanctions on Russia should it exercise its territorial ambitions on Ukraine, and on Monday morning President Joe Biden made good on that threat, by issuing an executive order banning “new investment, trade, and financing by U.S. persons to, from, or in the so-called DNR and LNR regions of Ukraine.”

The latest update by the Wall Street Journal had Biden saying his administration will levy sanctions on two Russian financial institutions, its sovereign debt and elite individuals. Some US lawmakers are calling for harsher sanctions. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said any path forward should ensure that the Nord Stream 2 pipeline “not be allowed to ever proceed” and that Moscow should be made to pay a far heavier price than it did for previous invasions of Georgia and Ukraine.

(On 12 September 2014, the United States imposed sanctions on Russia’s largest bank (Sberbank), a major arms maker and arctic (Rostec), deepwater and shale exploration by its biggest oil companies (Gazprom, Gazprom Neft, Lukoil, Surgutneftegas and Rosneft — Wikipedia)

As US and European retaliation for what they consider to be an act of aggression against Russia’s pro-Western, democratic neighbor continues to solidify, prices are soaring on a number of key metals that Russia supplies.

Commodities vulnerable to sanctions

While Russian metal producers have for the most part escaped Western sanctions, an exception is Rusal. The world’s largest aluminum producer outside China was included among a set of sanctions imposed by the United States between April 2018 and early 2019. Rusal last year mined about 3.8 million tons of the lightweight metal, about 6% of world production. The aluminum market is running low on supplies, causing prices to near a 13-year high earlier this month.

“Bullish factors include power costs having spiked due to winter and Russia capping gas supply, which in turn had prompted production cuts leading to supply shortages,” Liberum head of commodities strategy Tom Prices told S&P Global Platts.

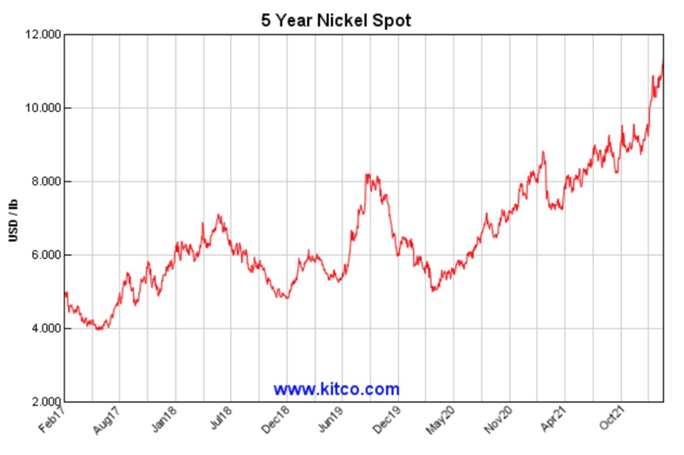

Nickel is similarly undersupplied. It jumped to an 11-year high of $25,000 a ton, Monday, on fears of dwindling supplies that are already at a low level.

The base metal used in stainless steel and lithium-ion battery cathodes advanced as much as 3.2% to $25,135/t. ($11.40/lb). According to Bloomberg it’s the top performer on the London Metal Exchange this year, climbing amid a wave of forecasts that supply will fall short of rapidly growing demand from the electric-vehicle industry.

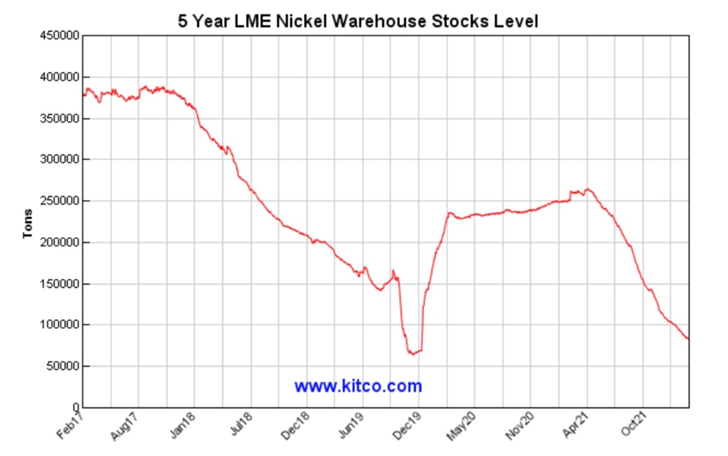

The nickel market’s tight fundamentals are reflected in warehouse inventories which have dropped to their lowest since 2019. Nickel is now in “steep backwardation,” referring to a condition when spot prices are much higher than futures. So far prices are up 18% in 2022.

Russia is the third largest nickel producer in the world, behind only Indonesia and the Phillipines. In 2021 it mined 250,000 tonnes, including 193,006t from Nornickel, the globe’s top producer of refined nickel. Norilsk Nickel’s output amounts to around 7% of global mine production, which in 2021 was 2.7 million tonnes, according to the USGS.

Other metals likely to feel the effects of Western sanctions on Russia, whether or not they are targeted directly, include copper, cobalt, gold, palladium and platinum.

The USGS says Russia produced 920,000 tonnes of refined copper last year, about 3.5% of the world total. Close to half, 406,841t, was mined by Nornickel, with UMMC and Russian Copper Company being the other two main producers.

Nearly three-quarters of the world’s cobalt is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with China having a lock on the refining of the metal used in EV battery cathodes. While far behind the DRC’s 170,000 tonnes produced last year, Russia’s 7,600t of mined cobalt puts it in second place, accounting for more than 4% of the world total.

Nornickel is the largest cobalt producer in Russia, the globe’s biggest producer of palladium, and a major miner of platinum. Last year it produced 2.6 million ounces of palladium or 40% of global mine production, and 10% of world platinum production or 641,000 ounces.

Russia isn’t top of mind when it comes to gold mining, but the country is the third largest producer following Australia and China. According to the World Gold Council, in 2021 Russian gold production amounted to 3,500 tonnes, including output from Polyus and Polymetal.

Russia also produced 76 million tonnes of steel last year, nearly 5% of the world’s total, and a large percentage of its diamonds. State-controlled Alrosa is the planet’s largest producer of rough diamonds. In 2021 it mined 32.4 million carats, about 30% of the world total, exporting mostly to Belgium, India and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Beyond metals, Russia is a huge producer of potash, phosphate and nitrogen used in fertilizers, representing more than 50 million tonnes, or 13% of global annual fertilizer output.

Finally, Russia is the world’s largest wheat exporter, producing 76 million tonnes last year with Turkey and Egypt among its main buyers. Reuters reports the US Department of Agriculture expects Russia to export 35 million tonnes of wheat in the July-June season, 17% of the global total.

Wheat exports are particularly at risk of supply disruptions resulting from a conflict between Russia and Ukraine. A war could affect commercial shipping in the Black Sea, the main wheat export route of the two countries.

Sulfide nickel importance

A disruption to nickel supplies would not only harm nickel end users, but the entire lithium-ion battery supply chain because Nornickel mines sulfide nickel, the kind of nickel best suited to lithium-ion batteries.

To digress briefly: what’s important is the type of nickel needed to make batteries.

Producing nickel-rich battery cathodes requires high-purity nickel, in the form of nickel sulfate, derived from ‘Class 1’ nickel sulfide deposits. This nickel can be processed at relatively low cost, and with minimal waste, using a simple flotation technique.

However, there is a problem, in that the majority of today’s nickel production is nickel pig iron (NPI) used in steelmaking (also known as ferro-nickel), which is ill-suited for making battery-grade nickel.

Another problem is the rarity of nickel sulfide deposits. Nickel deposits come in two forms: sulfide or laterite. About 60% of the world’s known nickel resources are laterites, which tend to be in the southern hemisphere. The remaining 40% are sulfide deposits.

Existing sulfide mines are becoming depleted, and nickel miners are having to go to the lower-quality, but more expensive to process, as well as more polluting nickel laterites such as found in the Philippines, Indonesia and New Caledonia.

In Indonesia, nickel is produced from laterite ores using the environmentally damaging HPAL technique. The advantage of HPAL is its ability to process low-grade nickel laterite ores, to recover nickel and cobalt. However, HPAL employs sulfuric acid, and it comes with the cost, environmental impact and hassle of disposing the magnesium sulfate effluent waste. The Indonesian government only recently banned the practice of dumping tailings into the ocean for new smelting operations, and it isn’t yet a permanent ban.

Chinese nickel pig iron producers in Indonesia now are looking to make nickel matte, from which to turn laterite nickel into battery-grade nickel for EVs. The process however is highly energy-intensive and polluting, as well as far more costly than a nickel sulfide operation (up to $5,000 per tonne more).

According to consultancy Wood Mackenzie, the extra pyrometallurgical step required to make battery-grade nickel from matte will add to the energy intensity of nickel pig iron (NPI) production, which is already the highest in the nickel industry. We are talking 40 to 90 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per tonne of nickel for NPI, versus under 40 CO2e/t for HPAL and less than 10 CO2e/t for traditional nickel sulfide processing. Read more

Electrification demand

While only 10% of the world’s nickel currently ends up in the battery supply chain, the growth in EV demand is expected to transform the market.

Bank of America forecasts that 690,000 tonnes of nickel will be needed by 2025, based on its estimate of 13.6 million EVs sold that year. That represents more than the combined nickel supply of Russia and the Philippines, which in 2021 outputted 620,000 tonnes, out of the 2.7Mt total.

If we take that number out and apply it to EVs, the mining industry has to find another 690,000 tonnes to supply all of nickel’s other uses, the primary one being stainless steel.

Nickel sulfate powder made from nickel sulfide ore, is a crucial ingredient in cathode formulation for lithium-ion batteries needed to propel electric vehicles.

Nickel is popular with EV battery-makers because it provides the energy density that gives the battery its power and range. Increasing the amount of nickel in a battery cathode ups its power and range.

Recent data from Adamas Intelligence shows global EV sales nearly doubling year on year in 2021, i.e., growing by 83%. The record 286.2 gigawatt hours of battery capacity deployed in passenger vehicles represented a 113% leap over 2020.

It’s important to note that over half of that battery capacity (54%) was powered by high-nickel cathode chemistries, referring to NCM 6-, 7- and 8-series (nickel-cobalt-manganese), nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) and nickel-cobalt-manganese-aluminum (NCMA). Low-nickel chemistries only amounted to 26% and no-nickel batteries were just 20%.

According to Adamas, high-nickel battery chemistries were most prevalent in North America, used by manufacturers such as Tesla, VW, Ford, Hyundai and others.

Reuters noted in a recent piece that The EV revolution seems to be fast approaching a state of critical mass, which is translating into record-breaking price runs for cathode inputs such as nickel and cobalt and, of course, lithium itself.

Again it comes down to supply, with Class 1 nickel containing a minimum 99.8% metal. That’s why there is such a scramble for battery-grade nickel, and why the amount stored in LME and Shanghai Futures Exchange warehouses is so low.

Reuters reports Shanghai nickel inventories have been running on empty for months and are currently sitting at just 5,301 tonnes. LME nickel stocks are currently at 83,274 tonnes, of which just over half has been canceled. This compares to 295,000 tonnes of nickel last year.

Columnist Andy Home notes that the nickel being mined and processed in Indonesia “isn’t going to go anywhere near an exchange warehouse” because it’s in the wrong form to qualify for exchange delivery. Moreover, because most nickel produced in Indonesia is by Chinese companies, “supply will ultimately be channeled to Chinese battery makers to meet domestic demand.” Translation: this nickel won’t go into metal exchange warehouses, it will go directly to China.

With so little battery-grade nickel available to the market, it seems the supply-demand imbalance problem is unlikely to be solved, especially as demand keeps building.

Consider: global carmakers have committed to spending just over half a trillion dollars on EVs and batteries, motivated by an added sense of urgency by many countries to do more to combat climate change, and looming carbon mandates in major cities such as London and Paris.

The $515 billion in auto-industry EV commitments made last year is nearly double the $225 billion on capital expenditures and R&D in 2020, according to AlixPartners.

Mercedes-Benz is latest major automaker to up its zero-emissions game, announcing that by 2025, all-electric and hybrid vehicles are expected to make up 50% of sales. The luxury car company also expects to have factories exclusively producing electric vehicles by the end of the decade, with some production lines switching over even sooner. Mercedes plans to launch production of its EQE model in Germany later this year.

The bullish market forces swirling in preparation for what many are calling the next commodities supercycle, driven by so-called “green economy” metals, is excellent news for companies on the hunt for raw materials to feed these new technologies.

Palladium One Mining

In Canada, the largest nickel deposits are found in the Thompson Nickel Belt in Manitoba, Ontario’s Sudbury Basin and the Ungava Peninsula in Quebec. Like Sudbury, Vale’s Voisey’s Bay operation in Labrador has long been one of the biggest nickel producers globally.

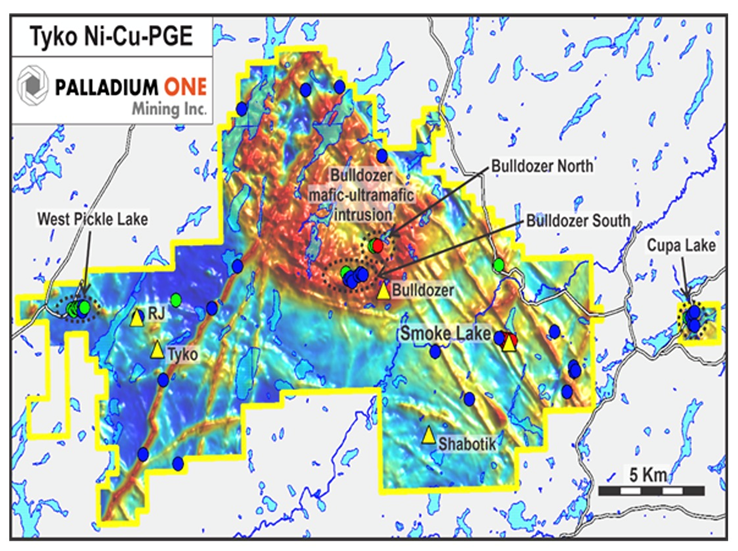

One project resembling Voisey’s Bay-style nickel-copper-PGE mineralization is the Tyko project near Marathon, Ontario, being developed by Palladium One (TSXV:PDM, FSE:7N11, OTC: NKORF).

Palladium One continues to outline a high-grade nickel-copper system, where a second-phase drill program in 2021 and an announced expansion increases Tyko by over a fifth.

At PDM’s Tyko, its main metals are nickel and copper, while at its LK project in Finland, PDM is exploring for palladium, platinum, nickel, copper and cobalt.

Combined, Tyko and LK offer investors nearly equal exposure to battery metals and precious metals — the latter in the form of platinum and palladium. Note: precious metals refers to palladium, platinum and gold.

In Finland, months of drilling success on Palladium One’s Läntinen Koillismaa (LK) PGE-Cu-Ni property have culminated in a much-increased resource endowment, further confirming the project’s potential to host a large bulk-tonnage deposit.

Renforth Resources

Also looking to benefit from the clean energy era is Renforth Resources (CSE:RFR, OTCQB:RFHRF, FSE:9RR) which holds a district-scale battery metals prospect at its Surimeau project in Quebec.

This 260 square-kilometer property hosts several target areas for industrial metals (nickel, copper, zinc, cobalt), located south of the Cadillac Break, a major regional gold structure.

Exploration focus is currently on the sulfide nickel-rich VMS targets, in particular the Victoria West prospect, which has been the site of drilling for over a year.

According to Renforth, information gleaned from drilling and trenching the Victoria West target, along with surface sampling, creates an area of interest that includes about 5 km of strike on the western end of a 20-km magnetic anomaly.

The company interprets this anomaly to be a nickel-bearing ultramafic sequence unit, which occurs alongside, and is intermingled with, VMS-style copper-zinc mineralization.

Management considers the style of mineralization to be an “Outokumpu-like” occurrence, referring to a district in eastern Finland known for several unconventional sulfide deposits with economic grades of copper, zinc, nickel, cobalt, silver and gold.

Conclusion

Nickel and other metals supplied by Russia, such as palladium and cobalt, are currently under supply pressure.

A string of annual deficits starting in 2018, combined with higher sales of gasoline vs diesel units, culminated in palladium’s historic $2,830 per ounce in May, 2021. While prices have since softened, a rebound in auto production this year should create upside for palladium, Morgan Stanley said in a 2021 year-end note.

If Russian mining companies enter the cross-hairs of Western sanctions, it will only worsen the supply-demand imbalance.

Meanwhile the demand pressure on these metals continues to build, boding well not only for their prices, but companies like Palladium One and Renforth that are unlocking deposits that will help supply a green-energy and transportation future.

Palladium One Mining

TSXV:PDM, OTC:NKORF, FSE:7N11

Cdn$0.19, 2022.02.22

Shares Outstanding 248m

Market cap Cdn$48.6m

PDM website

Renforth Resources

CSE:RFR, OTCQB:RFHRF, FSE:9RR

Cdn$0.065; 2022.02.22

Shares Outstanding 262.3m

Market cap Cdn$17.0m

RFR website

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Richard owns shares of Renforth Resources (CSE:RFR), Both Palladium One Mining (TSXV:PDM) and Renforth Resources (CSE:RFR) are paid advertisers on Richard’s site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.