East eats wests copper breakfast, lunch and supper

2021.08.23

Commodities are considered one of the best places to park investment capital during periods of rising inflation.

The reason is simple. As demand for goods and services rise, so do their prices, along with the raw materials (commodities) needed to produce the finished products. Investing in commodities is therefore considered a hedge against inflation.

The US economy is currently running hot, owing to massive federal stimulus and a waning coronavirus pandemic (even factoring in the recent surge in cases due to the Delta variant), and that has caused demand for goods and services to outstrip the ability of companies to supply them.

Toss in virus-related supply chain bottlenecks, including a shortage of labor in some industries, rising freight rates, and companies having to frantically restock drawn-down inventories, amid high demand, and we have the biggest inflation increase in more than a decade. Consumer prices marched 5.4% higher in June, the biggest monthly gain since August 2008 (the July figure is also 5.4%).

From the bottom of the last commodities “super-cycle” in 2003 to the peak in 2008, commodities rose over 300%.

Many are pointing to the formation of a new super-cycle, driven not by fossil fuels and the rise of China, such as occurred in the 2000s, but by so-called “green” metals needed to electrify and decarbonize, to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

On top of surging demand for metals needed to feed new solar & wind power installations, lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and grid-scale utility storage, and traditional “blacktop” infrastructure programs (eg. roads & bridges), we have current and emerging structural deficits for several metals, that will keep prices buoyant for the foreseeable future.

Over the past year, tight supply is reflected in the rising prices of copper, nickel, zinc, and lead.

Price increases are happening not only for industrial metals but a range of other commodities including food staples.

In Brazil, the worst water crisis in 100 years is affecting the nation’s export crops including coffee, corn, sugarcane and oranges. Yields for the corn crop could hit a five-year low and coffee production this year is forecasted to drop as much as 30% below normal levels.

Drought conditions on both sides of the US-Canada border have forced farmers to sell their low-yielding wheat and barley as animal feed. Earlier this summer the region’s spring wheat prices recently hit their highest level in more than eight years.

Hay crops are only 10 to 25% of normal and some ranchers are selling off parts of their herds due to a shortage of feed.

“Producers have chosen to cut small grain fields for hay versus harvesting them for grain as there just isn’t enough forage to bale,” BNN Bloomberg quoted Jeff Schafer, president of the North Dakota Stockmen’s Association, adding that “Grains that should be ‘armpit high’ are ‘boot-high’ at best and typically you can see a gopher run in front of your cutter bar.”

There are demand-driven reasons keeping commodity prices higher, and structural issues surrounding the supply of certain minerals. First, the demand side.

China, the world’s second biggest economy and the top commodities consumer, has emerged from the pandemic relatively unscathed. Industrial production surged 6.6% in May and first-quarter GDP rose an astonishing 18.3%, the most since China began keeping quarterly records in 1992. High Chinese demand for iron ore used in steelmaking, copper, zinc and nickel, have kept the prices of these industrial metals buoyant.

To transition from a fossil fuel-based economy to one run on clean power including the electrification of the global transportation system will require a colossal boost in the production of mined materials, including copper, silver, zinc, nickel, tin, lithium and palladium.

That is why Goldman Sachs and other influential voices are calling this the new commodities super-cycle.

Higher penetration of solar, wind and energy storage all will require copious metals.

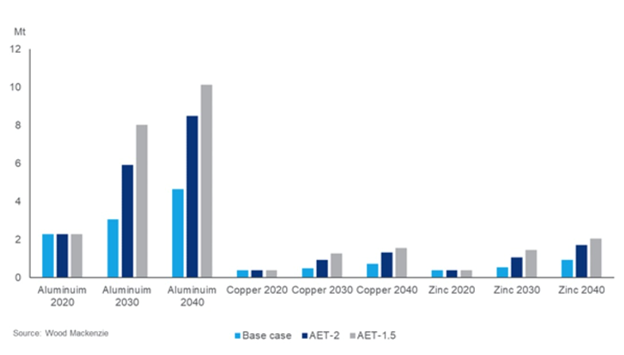

The future looks particularly bright for solar, states a new report from Wood Mackenzie, thus presenting an opportunity for base metals. The Scotland-based commodities consultancy predicts that usage of aluminum, copper and zinc in photovoltaics will double by 2040, prompting an increase in demand.

“Base metals are an integral component of solar power systems. A typical solar panel installation requires aluminum for the front frame and a combination of aluminum and galvanized steel (zinc) for structural parts. Copper is used in high and low voltage transmission cables and thermal solar collectors,” Kamil Wlazly, Wood Mackenzie’s senior research analyst, wrote in the report.

As the cost of solar power installations drop, solar’s share of total power supply is expected to increase and may displace other forms of electricity generation, according to Wlazly.

Under a base case scenario, consistent with a 2.8 to 3˚C global warming view, the report expects aluminum demand from solar to rise from 2.4 million tonnes in 2020 to 4.6Mt in 2040; base case copper demand would go from 0.4Mt in 2020 to almost 0.7Mt; and global zinc consumption would double from 0.4Mt 0.8Mt in the base case.

As for increased solar uptake in the United States, a wrench was recently thrown into that plan by the Biden administration. The White House announced steps in June to crack down on forced labor in the supply chain for solar panels made in the Chinese region of Xinjiang. Although the administration wants to expand the use of solar power to reach its climate goals, it will have a difficult time doing so considering that China dominates the supply chain for solar power particularly the mining of polysilicon. Cutting off access to some imports could make it harder or more costly for the United States to expand solar use domestically, the New York Times reported.

Important as the demand story is, structural supply issues are arguably the more powerful driver of surging commodity prices.

Pandemic-related restrictions at workplaces, including mines, led to copper mines in the top two producers, Chile and Peru, shutting down for at least part of 2020. Other mining companies had to cut capacity to comply with distancing measures.

Covid also messed up planning. When practically the entire world locked down in March, 2020, many lumber producers shuttered operations and sold off inventories. An unexpected housing surge owing to rock-bottom interest rates saw lumber prices shoot five times higher than pre-pandemic levels, reaching an all-time record $1,670 per thousand board feet.

Most businesses drew down inventories to the bare minimum to weather the downturn but were caught flat-footed when demand accelerated amid vaccination rollouts in early 2021.

Bullish market fundamentals for commodities pushed the Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index hit a 10-year high and is close to matching the record set in 2011, the height of the last commodities super-cycle. Materials with excellent price performances include copper, which in May hit a record high $10,460 a tonne and continues to trade in that range; Brent crude oil which has doubled in price since November 2020; steel prices which are up over 200% since the start of the pandemic; and a number of agricultural commodities such as corn, soybeans, coffee and wheat.

However, despite the huge lift in prices, there is a “yawning gap” between where they are now and where they should be. In its Q2 wrap-up, commodities investment house Goehring & Rozencwajz posted a 120-year chart comparing commodity prices to the Dow Jones Industrial Average, going back to 1901. The result? “Real assets have never been as undervalued relative to financial assets,” according to the authors.

The chart, says G&R, shows that other major bottoms occurred in 1929, 1969 and 1999, indicating that like those cycle nadirs, now presents an “excellent time to establish real asset positions.”

“Prior catalysts have all been monetary related. This time likely as well,” the Wall Street firm noted.

Our main takeaway from the chart below is that commodities have never so undervalued, except for about 15 years between 1955 and 1970.

Copper

Taking a 30,000-foot view of the entire commodities complex, copper is the one material that stands out as more bullish than the others, owing to tight supply conditions matched against explosive future demand.

Copper’s widespread use in construction wiring & piping, and electrical transmission lines, makes it a key metal for civil infrastructure renewal.

A report by Roskill forecasts total copper consumption will exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization and electricity demand. Total world mine production in 2020 was only 20Mt.

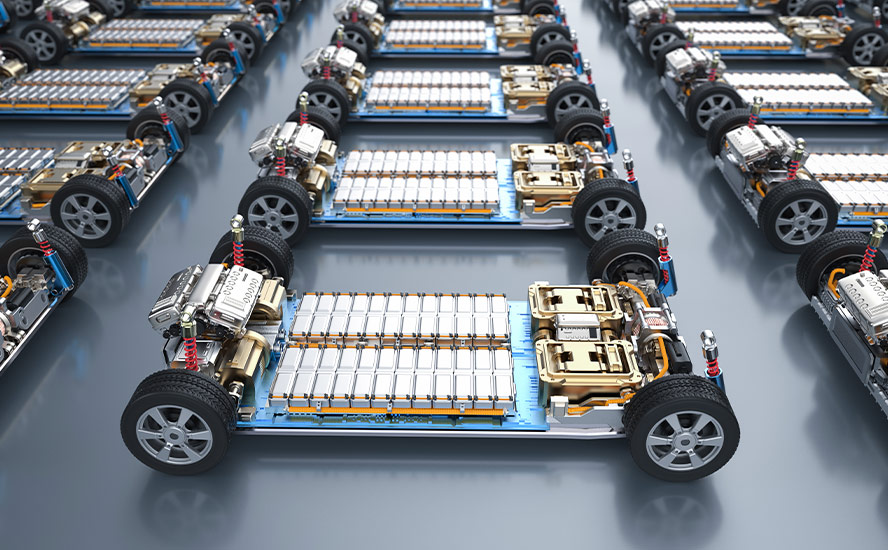

The continued movement towards electric vehicles is a huge copper driver. EVs use about four times as much copper as regular internal combustion engine vehicles.

Electrification includes not only cars, but trucks, trains, delivery vans, construction equipment and two-wheeled vehicles like e-bikes and scooters.

The latest use for copper is in EVs and their charging stations, renewable energy, particularly in photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines. The base metal is also a key component of the global 5G buildout. Even though 5G is wireless, its deployment involves a lot more fiber and copper cable to connect equipment located within a building.

But this hurtling freight train of copper demand is about to slam into the immovable object of a supply crunch.

Some of the largest copper mines are seeing their reserves dwindle; they are having to dramatically slow production due to major capital-intensive projects to move operations from open pit to underground. Examples include Grasberg in Indonesia, the world’s second largest copper mine. The mine began as a large open pit but after decades of extracting it, the easy-to-reach ore is gone and future production is expected to come from a deep cave deposit known as the Deep Mill Level Zone. Copper concentrate exports have plunged dramatically as operations shift from open pit to underground.

In Chile, a $5 billion expansion at Chuquicamata, also moving operations from open pit to underground, will take five years to reach full output of 300,000 tonnes per annum — this is not new production.

Shipments from BHP’s Escondida took a hit in 2019 due to operations moving underground. The largest copper mine on the planet is expected to take until 2022 to re-gain full output, again not new production.

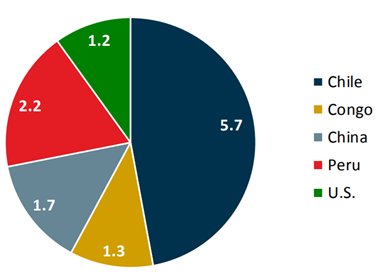

These cuts are significant to the global copper market because Chile is the world’s biggest copper-producing nation — supplying 30% of the world’s red metal. Adding insult to injury, copper grades have declined about 25% in Chile over the last decade, bringing less ore to market.

In fact the world could face a large shortfall in the next decade unless the copper mining industry makes major investments. According to CRU Group, via Bloomberg, the industry needs to spend upwards of $100 billion to close a potential annual supply deficit of 4.7 million tonnes by 2030, as the clean power and transportation sectors call for much higher demand. Closing this gap would require building the equivalent of eight “Escondidas”, referring to the world’s largest copper mine in Chile.

StoneX, a Fortune-100 financial services firm, forecasts copper demand in 2021 will rise about 5% compared to last year, moving global copper supply from a small surplus in 2020 to a more than 200,000-tonne deficit.

One of the problems with copper is it is difficult to find in large enough amounts close to surface, where it’s economical to extract. It also takes many years to bring a copper deposit into production, especially in places like the United States and Canada where miners face strict permitting regulations that can cause delays. According to Bloomberg Intelligence, the average lead time from first discovery to first metal has increased by four years from previous cycles, to almost 14 years.

“Increasing technical complexity and approval delays could lead to a dearth of shovel-ready projects in 2025-30,” Bloomberg Intelligence analysts Grant Sporre and Andrew Cosgrove wrote in a recent report. The authors added:

“After China’s State Reserve Bureau mopped up all of the excess copper from 2020’s Covid-19 slowdown, the market now looks fundamentally tight, with our analysis pointing to at least two years of deficits. With these shortages, alongside investor interest in copper’s decarbonization credentials, we think a price above $8,500 a ton ($4.25/lb) is well supported.”

A recent report by Goehring & Rozencwajg Associates, mentioned once already, found stagnating supply is a key factor pushing “copper prices far higher than anyone expected.”

Last week the spot copper price rose after workers at Codelco’s Andina mine in Chile went on strike. The prospect of more production cuts pushed spot copper to $4.43 a pound. The red metal has had quite a run in 2021, with prices advancing 49% over the past year.

According to G&R, the number of new world-class discoveries coming online this decade “will decline substantially and depletion problems at existing mines will accelerate.”

Also, geological constraints surrounding copper porphyry deposits, a subject few industry analysts let alone investors understand, will contribute to the problems, the report said.

By 2015, the industry’s head grade was already 30% lower than in 2001, and the capital cost per tonne of annual production had surged four-fold during that time — both classic signs of depletion.

According to the Goehring & Rozencwajg model, the industry is “approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades,” and brownfield expansions are no longer a viable solution.

“If this is correct, then we are rapidly approaching the point where reserves cannot be grown at all,” the report concluded.

It also shines a light on the importance of making new discoveries in establishing a sustainable copper supply chain.

Over the past 10 years, greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically, with tonnage from new discoveries falling by 80% since 2010.

We just came across some startling statistics indicating the extent to which copper supply is falling short of demand. It comes via CRU a leading authority on copper.

This data is the most compelling argument yet of the need to develop existing and new deposits of copper if we are to have any hope of meeting future demand.

For starters, CRU estimates that by 2031, the copper supply gap, referring to the difference between committed mine production and demand for primary copper, will reach 5,935 kt.

Is there anything in the copper pipeline that could relieve this supply pressure? There is some really interesting data, again from CRU, concerning potential production from uncommitted projects.

Global uncommitted projects are classified as probable, possible or speculative. CRU estimated the sum total of all three project categories as 12,145 kt by 2031.

This is a sizeable figure. However the question is how much of this uncommitted production will get board, government or the people’s approval to go ahead? A second bigger question is how much of anticipated future committed/ uncommitted copper production is actually controlled by Western interests? This is a very legitimate question and is of real concern. Much of the world’s future copper supply is locked up by countries whose interests might not be fully aligned with those of say the US. A lot of committed/ uncommitted copper will never reach the global market because it is already tied up in offtake agreements.

We can only guess the percentages. But a little back of the envelope math indicates how tight the current market is, and how quickly any talk regarding yearly copper surpluses is going to fade away.

12,145 kt – 5,935 kt = 6,210 kt surplus by 2031.

A 6,210 kt surplus sounds pretty good. Until we consider the following:

According to CRU there is 12,145 kt of uncommitted possible copper production between now and 2013:

- probable (4,000 kt)

- possible (6,600 kt)

- speculative (1,500 kt)

From CRU analysis of projects in 2015 and their 2020 status:

- 80% of all committed projects in 2015 had made it into production by 2020.

- 47% of all probable projects in 2015 had become committed by 2020 and 13% of all probable projects in 2015 were operating by 2020.

- 55% of all possible projects in 2015 remained possible by 2020, but 26% had been canceled; only 6% of possible projects had become committed by 2020.

In the table below, CRU provided us with a breakdown of where future (2031) production is located. Notice that Chile tops the list followed by the DRC, Peru and Indonesia.

We also know that new supply is mostly concentrated in just five mines — Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC. Three of these mines are in Chile, one is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the fifth mine is in Panama.

At Cobre Panana, nearly half of the 300,000 tonnes per year (tpy) production goes to Korea. Under a 15-year offtake agreement, Canadian miner First Quantum Minerals will ship 122,000 tpy of copper concentrates per year from Cobre Panama to South Korean copper smelter LS Nikko.

The Kamoa-Kakula copper project is a joint venture between Ivanhoe Mines (39.6%), Zijin Mining Group (39.6%), Crystal River Global Limited (0.8%) and the DRC government. Kakula reached commercial production on May 25, 2021, and while output is currently set for 200,000 tpy in Phase 1, a second phase would add 200,000 tpy and peak production would exceed 800,000 tpy.

In June Ivanhoe signed two offtake deals, one with a subsidiary of its partner firm, China’s Zijin Mining; the other with Chinese commodities trader CITIC Metal, to sell each 50% of the copper production from Kakula — the first of two mines involved in the joint venture. In other words, 100% of Kamoa-Kakula’s Phase 1 production goes to China.

That leaves three mines in Chile — Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca’s “QB2” expansion. In 2016 BHP, the majority owner of Chile’s Escondida, the largest copper mine in the world, committed to spend just under $200 million to expand its Los Colorados concentrator. The expansion would help offset declining ore grades and add incremental copper production to reach an average 1.2 million tonnes a year over the next decade. BHP owns a 57.5% share in Escondida, Rio Tinto owns 30%, and the remaining 12.5% is owned by JECO Corp and JECO2 Ltd.

JECO is a Japanese joint venture between Mitsubishi Nippon Mining & Metals and Mitsubishi Materials Corp. It is not immediately clear whether any of Escondida’s production is bought by JECO Corp.

BHP said in February that the expansion of its Spence mine is expected to be completed within one year. Once the operation hits full production, it would produce 300,000 tpy until at least 2026. Spence ownership is split 50-50 between BHP and Santiago-based Minera Spence SA.

Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 project is expected to produce 316,000 tpy of copper equivalent for the first five years of its 28-year mine life. In 2019 the Canadian company closed a $1.2 billion transaction whereby Tokyo-based Sumitomo Metal Mining and Sumitomo Corp will, through an $800 million and a $400 million contribution, acquire a 30% interest in project owner Compañia Minera Teck Quebrada Blanca S.A. (“QBSA”). Like Escondida, it is unclear whether the two Japanese companies will take a portion of QB2’s production, or whether they will simply share in the profits.

Summing up, our analysis shows that in two of the five mines where new copper supply is concentrated, there are offtake agreements in place with non-Western buyers. In the case of Kamoa-Kaukula, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project. Nearly half of Cobre Panama’s annual production goes to a Korean smelter under a 2017 offtake agreement.

Now, we can’t obviously say, because it’s too early, what percentage of CRU’s expected 12,145 kt of production in 2031 will actually make its way into global copper supply.

However it is reasonable to expect that some percentage will be set aside for offtake agreements and that the most likely recipient of those offtakes is China, which currently consumes half of the world’s copper supply.

Remember, only 6% of possible projects in 2015 had become committed by 2020 and 26% had been canceled. Of probable projects in 2015, less than half (47%) had become committed by 2020, and only 13% were operational.

Despite the best laid plans copper mines never reach their yearly production milestones. Globally we must factor in between an 800,000-tonne and 1.2 million-tonne annual aggregate loss, due to any number of factors beyond their control. This includes mine strikes, port strikes, work stoppages due to earthquakes, floods, or the latest output interruption, covid-19.

Hardly confidence-building statistics that we will be adequately supplied with copper in 2031. And the supply situation is going to get worse. The reality is there are factors interfering with global copper production; the two most serious — climate change and resource nationalism — are occurring now and increasing in intensity.

Resource nationalism

With commodity prices soaring on tight supply and heavy demand, as the world’s biggest economies revive following a year of coronavirus-related restrictions, the temptation for producer nations to cash in on more valuable mineral reserves to pay for social programs is proving hard to resist.

Resource nationalism is the tendency of governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over natural resources located on their territory.

The geopolitical landscape of the world’s top copper producers is changing.

Countries rich in minerals are frequently looking at ways to get more money from miners, the most common tactic being to hike royalty payments.

Governments have also gone beyond taxation in getting more out of the mining sector with requirements such as mandated beneficiation/export levies and limits on foreign ownership:

Mandated beneficiation/export levies – Governments are imposing steep new export levies on unrefined ores. Minerals processed in-country capture more of the value chain as the products achieve higher prices.

Increasing state ownership – Miners are easy targets because mining is a long-term investment and one that is especially capital intensive. Mines are also immobile, so miners are at the mercy of the countries in which they operate. Outright seizure of assets happens using the twin excuses of historical injustice and environmental or contractual misdeeds. There is no compensation offered and no recourse.

Risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft tracks incidents of direct expropriation and nationalization, summarizing the degree of risk in an annual resource nationalism index. The highest scores go to cases where there has been no compensation given, not adequate compensation, or where a government hasn’t paid an award to a company following arbitration.

The latest (2021) edition of the index ranks the highest-risk countries as Venezuela, Tanzania, Mexico, PNG, Zambia, Russia, North Korea, Kazakhstan, DRC and Zimbabwe.

Sixty six of 198 countries in the index, or 33%, have tightened their grip on resource wealth since 2017. Latin America stands out as the region where the risk of expropriation and tax increases have increased the most.

Mexico tops this list, driven by the López Obrador administration, whose agenda includes studying the possibility of nationalizing lithium assets, followed by the three largest economies in South America — Brazil, Argentina and Colombia.

According to Verisk Maplecroft, In Latin America, the push to gain greater benefit from natural resources generally hinges on two factors. In Mexico and Argentina, the main driving force is ideology, while in Colombia and Chile pressure comes from communities — both those hosting mining projects and civil society.

Chile and Peru are both seeking to raise the royalty tax on miners, while in the DRC, Africa’s top copper-mining country, the government earlier this year slapped a ban on the export of copper and cobalt concentrates — an action almost identical to what has happened in Indonesia with nickel.

Chile

The South American nation is fast becoming a liability for copper miners.

Triggered by the worst social unrest in a generation, anchored in rampant inequality, the country reportedly has just elected an assembly that will place responsibility for writing a new constitution in the hands of the left wing. At the start of August, Gabriel Boric, a candidate from the left-wing Apruebo Dignidad bloc, is leading the voting preferences.

The reforms could give more power to indigenous communities and expand water rights, including a potential ban on mining in areas where there are glaciers, along with increased state ownership of water desalinated by mining companies.

(The country’s water supply was privatized in 1981 under the military dictatorship. In Petorca province north of Santiago, a 10-year-long drought has forced the provincial government to buy and deliver water of dubious quality to 6,000 people in rural communities, about 20% of Petorca’s population, by truck).

There is also proposed legislation that, if approved by the Chilean Senate, would impose a royalty as high as 75% on sales of copper, if copper is above $4 like currently.

In a May note, Goldman Sachs said the new law could put at risk 1 million tonnes of annual copper supply representing about 4% of global output.

Peru

In neighboring Peru, the new left-wing administration of Pedro Castillo was recently installed, following a June 6 election.

Among his campaign promises, Castillo has vowed to take up to 70% of mining companies’ profits and introduce new royalties on mineral sales.

The copper-mining country, second only to Chile in terms of output, has 46 mining projects representing a potential investment of $56 billion in the pipeline.

Argentina

Experienced resource investors will recall how Argentina in 2011 ordered the repatriation of energy and mining companies’ export revenues, to slow capital flight estimated at around $3 billion per month. The following year, Argentina grabbed a majority stake in the nation’s biggest oil company, YPF, from Spain’s Repsol.

More recently, state energy companies are getting into the lithium business in Argentina, which hosts one third of the “lithium triangle” located in the Salar de Atacama. Bloomberg reported in June that YPF will explore for lithium and get involved in a bid for battery production through a new unit; while another state-run energy firm, Ieasa, has said it will incorporate lithium into its business strategy.

Argentina is trying to export its way out of an economic crisis that began three years ago. Inflation is currently running around 49% and negotiations with the IMF over the repayment of a $44 billion loan have stalled, spooking investors. In May beef exports were suspended for a month after local prices doubled. According to the Financial Times, Since 1950 the economy has been hit by repeated crises leaving the country suffering more time in recession than any other country except the Democratic Republic of Congo.

A number of foreign companies, including Walmart, have departed Argentina since left-leaning Peronist leader Alberto Fernandez was elected in 2019.

DRC

The DRC holds two major distinctions. First, it is the richest country in the world in terms of mineral wealth, at an estimated $24 trillion; and it is the country in which the highest number of people — estimates go as high as 10 million — have died due to war since World War II.

Ranked the 175th least-developed nation, out of 189, according to the United Nations Human Development Index, in 2018 it was estimated that 73% of the Congolese population, around 60 million people, lived on less than $1.90 a day, meaning about one in six living in extreme poverty.

This has put tremendous pressure on the government to extract higher resource rents from foreign mining companies.

In 2018 then-DRC President Joseph Kabila signed a law amending the 2002 Mining Code. The new code increased gold and copper royalties by a respective 1% and 1.5%, and designated cobalt — of which DRC is the world’s leading supplier — a strategic metal. Royalties on cobalt production were hiked by a factor of five, from 2% to 10%.

In May of this year the DRC government banned the export of copper and cobalt concentrate, the same month that Ivanhoe Mines’ massive Kamoa-Kakula copper project reached commercial production.

China is heavily invested in the DRC and buys nearly 100% of its cobalt. China Molybdenum is the world’s second largest cobalt producer and it owns the majority of the Tenke Fungurume mine in the DRC. China has a lock on the world’s refined cobalt — which includes the 20% of DRC production that is handled by Chinese middlemen who buy the cobalt and sell it to Chinese refiners.

Zambia

Copper is extremely important to Zambia’s economy, contributing nearly two-thirds of its exports. Verisk Maplecroft rated Zambia one of the riskiest nations for resource nationalism, following the country’s attempt to liquidate Konkola Copper Mines (KCM). This past February, a Zambian court threw out a motion by Indian mining company Vedanta Resources aimed at stopping a liquidator from splitting up its subsidiary KCM.

According to CNBC, President Edgar Lungu’s government also threatened to suspend Glencore’s license to operate the Mopani copper mine in April 2020, amid tensions over the use of the asset as a swing producer.

Zambia is reportedly considering an overhaul of it tax regime, despite the fact that copper miners there have halted $2 billion of planned investments because a 10% royalty tax introduced in 2019 makes the projects unviable, according to an industry lobby group.

Indonesia

In 2012 Indonesia announced that foreign ownership of some mines would be capped at 49% and gave companies who exceeded this threshold 10 years to sell their excess ownership percentage.

Control of Grasberg, the world’s second largest copper mine, changed in 2019 when Freeport McMoRan and Rio Tinto agreed to transfer their majority ownership to state-owned Inalum. Freeport had been fighting for years with the Indonesian government over control of the mine. Rio sold its share in the project for $3.5 billion.

Recently the government’s priority has shifted to the nickel mining industry; Indonesia is the world’s top producer of the metal used in stainless steel and lithium-ion batteries.

Last year, the Southeast Asian nation banned ore exports amid a plan to develop a complete nickel supply chain, meaning raw ore that was previously destined for processing overseas would be “beneficiated” locally. Indonesia wants to become a global hub for electric vehicle production, from extraction to processing into metals and chemicals used in batteries, all the way up to building EVs.

With so much resource revenue at risk, it seems insane for Chile, Peru, Zambia and the DRC, four of the world’s biggest copper producers, to be moving in an anti-mining direction

Moreover, what is going to happen to copper supply, amid all this resource nationalism? Will copper miners ramp up output even though doing so could mean a bigger chunk of profits goes to the state? Remember, if Chile’s law passes, mining companies will hand 75% of their profits to the government, as long as copper stays above $4 a pound, as most analyst expect it to.

Resource nationalism is putting a vice-like grip on the copper mining industry not only in Chile and Peru but in the top two African copper producers, the DRC and Zambia.

Climate change

A new report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says that unless rapid and large-scale action is taken to reduce carbon emissions, the average global temperature is set to cross the 1.5 degree Celsius warming threshold within just 20 years.

A rise of 1.5 C is considered to be the tipping point, beyond which further warming is expected to have disastrous economic, political and environmental consequences.

Extremely hot weather in western Canada and western United States this summer has resulted in hundreds of deaths from heat exposure. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) says July 2021 was the hottest month ever recorded.

We know that Chile, the world’s biggest copper producer, has problems with water and is having to desalinate seawater used for mining copper in the country’s arid north.

There are currently 15 desalination or seawater propulsion systems (use of non-desalinated seawater) expected to be operational by 2028, including one by Antofagasta’s Coquimbo mine, which involves building a 150-km-long water pipeline.

According to Mining Journal, a desalination plant adds at least $1 billion to a project’s capital expenditures, and up to $3 billion, as was the case for a desalination plant that BHP built for its Escondida copper mine in 2018.

Cochilco, the country’s copper commission, estimates the use of desalination by mining to increase 156% through 2030, with 90% of the desalinated seawater used for copper processing.

We are already seeing major copper mines in Chile having to curtail production due to water shortages brought on by a decade-long drought. Antofagasta this week announced it will be forced to cuts its copper production target this year from between 710,000 and 740,000 tonnes, down from its previous forecast of 730,000 to 760,000t.

Another 50,000 tonnes is at risk should the Chilean company delay the redesigning of a desalination plant at its flagship Pelambres mine slated to begin operating in the second half of 2022.

A Chilean court ordered BHP’s Cerro Colorado copper mine to stop pumping water from an aquifer over environmental concerns, Reuters reported on Thursday.

In a thorough analysis of the DRC’s climate vulnerabilities, the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs rated Congo the 12th most vulnerable country to climate change among 181, and the fifth least prepared. The Dutch report projects the DRC over the next century will experience 100% more dry spells during the rainy season; temperatures that exceed 1.5 degrees C; and an increase in extreme weather events, particularly flooding which brings soil erosion and crop failure.

In central Brazil, the worst water crisis in nearly 100 years has made navigation on one of the country’s most important river systems difficult, making it more challenging and costly to get its grains and iron ore to global markets. (June flows are @ 55% of the historical average).

Bloomberg reported that Below-average rainfall has created bottlenecks for the second year in a row at the Paraguay-Parana waterway, which is used by iron-ore giant Vale SA as a cheaper transport alternative to roads and rail. Shipments are at the lowest since Brazil’s waterway transportation agency, known as Antaq, began collecting data in 2010…

Mining trucks are overloading the main highway in the region and accidents are frequent, according to Jesse do Carmo, president of a local miner workers union.

Vale said it is using low draft vessels on the river, and is also transporting ore by road and rail in a safe and legal way to reach clients in Brazil and abroad.

Reuters said that severe droughts are drying up rivers and reservoirs vital for production of zero-emission hydropower in several countries. In some cases, this means governments will have to rely more heavily on fossil fuels, potentially setting back international efforts to fight global warming.

Without adequate water supplies, the mining of copper and most other minerals doesn’t happen. A lot of mines are in far-flung locations such as the Arctic, where polar warming is happening faster than elsewhere, putting operations and infrastructure at risk of flooding and damage from melting permafrost; and in parched regions like Chile’s Atacama Desert and the Middle East. The world’s four driest mines are in Chile and Egypt; all of them receive average annual precipitation of 0 mm. Only 0.5% of global water supplies is fresh water, and we are putting extreme pressure on this very limited amount through industrial activities like fracking and over-production of farmland leading to desertification and crop failure.

As climate change makes already scarce water and mineral resources more difficult and expensive to access, the protection of existing mines and the hunt for new deposits will intensify, resulting in potentially lower production, higher operating costs and conflicts between both water and land users.

With much of the world currently experiencing droughts, and signs of climate change occurring more frequently and powerfully, it seems to me that global warming poses a very real risk to future metals output.

Conclusion

Commodities right now are as undervalued as they’ve ever been in history, presenting an optimal buy-in point.

If I had to choose one commodity, whose bullish fundamentals stand out head and shoulders above the others, I would choose copper, the metal we’re betting our electrified and decarbonized future on.

With all that is happening on the demand side for copper, combined with the supply pressures outlined, we believe there is no getting around the fact that the copper market is not just undersupplied now, but will be vastly undersupplied in 10 years.

We have shown that four out of the five major copper projects in the pipeline right now either have offtake agreements in place with non-Western countries (South Korea and China), or the mines are partially owned by Japanese companies that have a say in where some of the mined copper is destined. (ie. Japan)

We make a clear distinction between global copper supply and the global copper market. Mined copper that is locked up by offtake agreements should not rightly be lumped in with global supply, because it will never reach the United States, Canada or Europe. Instead, this copper will go straight to smelters in China for use in Chinese industry, to South Korean smelters for South Korean industry, and to Japanese smelters for Japanese industry. We can hardly call this situation western security of supply, when most of the raw copper material (cathodes or concentrate) is going to China, South Korea and Japan, who then turn around and sell more expensive copper end products to North America and Europe.

We’re becoming short of copper in the West and there’s no two ways about it. We weren’t watching, we weren’t paying attention, we were asleep when China cornered the rare earths market back in 2010, and were also blind to the Chinese locking up global supplies & processing capabilities for nickel, cobalt, graphite and lithium.

Canada’s weak politicians preferred to export raw materials, mostly to China, meanwhile the US and EU went all “NIMBY.” Donald Trump’s solution was to slap China with hundreds of billions worth of tariffs, which did nothing to end China’s metal monopolies, and then along comes “sleepy Joe” Biden who claimed Americans need to invest more in infrastructure, sourcing the raw materials from Canada, and a whole host of other much less friendly places, to avoid China “eating our lunch”. Well Joe, the Chinese long ago ate your breakfast, your lunch and your dinner too.

Then you look at what’s happening in four of the world’s largest copper-producing countries, Chile, Peru, Zambia and the DRC, all of which are rising threats for resource nationalism, making the required ramp-up in copper production to meet expected demand from electrification/ decarbonization all that much harder, if not impossible.

The other countries on the CRU’s list of countries from which 2031 copper production is anticipated, are no more friendly to Western interests. We are talking about Russia and Iran, both subject to US sanctions, Mexico whose nationalist government is the most likely among Latin American countries to expropriate mines or hit them with higher taxes, and Indonesia which already has a template for local ore beneficiation. Also, the Indonesian government owns Grasberg, the world’s second largest copper mine, finally wresting it from Freeport McMoran and Rio Tinto after many years of conflicts over ownership.

None of these issues are going to be fixed in a decade, in fact there is every chance they will get worse, especially given that we have to consider the impacts of climate change on future copper production.

We therefore foresee copper prices continuing to rise (short-term prices will fluctuate but the long-term copper bull trend will stay intact) and the junior resource companies that own new copper deposits, the world’s future copper mines, becoming increasingly valuable targets for copper majors and mid-tiers seeking to replace their dwindling and lower-grade reserves.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.