De-dollarization has begun

2019.07.03

In the 1960s, French politician Valéry d’Estaing complained that the United States enjoyed an “exorbitant privilege” due to the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency. He had a point.

Because the dollar is the world’s currency, the US can borrow more cheaply than it could otherwise (lower interest rates), US banks and companies can conveniently do cross-border business using their own currency, and when there is geopolitical tension, central banks and investors buy US Treasuries, keeping the dollar high and the United States insulated from the conflict. A government that borrows in a foreign currency can go bankrupt; not so when it borrows from abroad in its own currency ie. through foreign purchases of US Treasury bills.

The dollar is the most important unit of account for international trade, the main medium of exchange for settling international transactions and the store of value for central banks. The Federal Reserve is the lender of last resort, as in the 2008–09 financial crisis, and is the most common currency for overseas borrowing by governments and businesses.

Wall Street generates significant income from selling banking services in USD to the rest of the world, and the US manages the world’s most important settlement systems, allowing it to monitor and limit funds used for illegal activities.

Barry Eichengreen, author of ‘Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System’, names three unique attributes to the dollar that no other currency has. As quoted by DW, these are:

- Size: Due to the size of the US and its economy, there are more dollars available than other currencies.

- Stability: US Treasuries have historically been valued as a safe financial instrument that is backed by the US government, which pays its bills on time.

- Liquidity: Treasuries can easily be bought and sold without them losing much of their value, given the consistent strength of the dollar. The bond market for US Treasuries is considered the most liquid financial market in the world.

Shunning the buck

The dollar is still the reserve currency, but how important is it right now, with all that is going on in the world? Such as: trade wars, central banks dumping Treasury bills and buying gold, US interest rates likely to fall and take the greenback down with them, and President Trump’s preference for a low dollar in order to cheapen US export prices and narrow the $891 billion trade deficit racked up in 2018.

Fortunately, we have a tool to measure the dollar’s popularity, but for dollar watchers, it’s not looking good. Every quarter the International Monetary Fund (IMF) releases a report on global foreign exchange reserves.

According to the IMF report, the dollar’s share of global foreign currency reserves in Q2 2019 fell for the sixth straight quarter, to the lowest level since 2013. Tellingly, the fall corresponds to when Trump took office as the 44th president. In January 2017, Trump’s inauguration, the ratio was 65.4%. In the first quarter of 2019 it was 62.5% and in the second quarter it slipped to 62.3%.

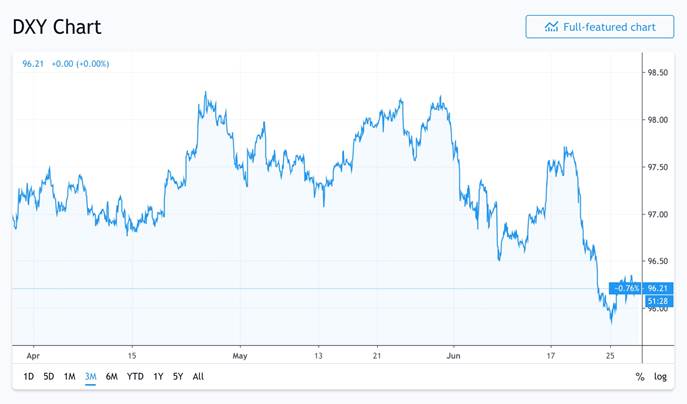

That may not seem like a big deal, just two-tenths of a percentage points between Q1 and Q2, but the slide becomes more significant when one realizes that the dollar was rallying at the same time as the ratio was falling. Indeedthe USD enjoyed a huge rally in the second quarter, surging 4.52%. That means holders of US dollars including central banks, sovereign wealth funds, etc., were selling dollars even while the value of the USD was climbing. Why would they do that? Likely they figured the dollar would in fact fall, longer term, therefore it was a good time to exit positions.

In providing these IMF figures, Bloomberg notes the last time mass dollar sales corresponded with a rise in the buck, was in the final three months of 2008 – when there was perceived to be a high risk of the global financial system collapsing.

We aren’t suggesting that is going to happen but…

The fact that the dollar’s share of global reserves edged lower in the face of a big rally may be a clear sign that foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds and institutional investors see increased risks from holding dollars as the U.S. government rams up its borrowing to unprecedented levels to pay for what is soon to be a $1 trillion budget deficit. – Bloomberg

Consider that the US debt is currently over 22 trillion dollars and climbing, and is running a budget deficit 3.7% of GDP – the highest ratio in the developed world.

Bloomberg notes it shouldn’t be that big a problem because the US can just pull a Ben Bernanke and “helicopter in” trillions worth of newly-minted currency to pay off the debt – something it alone can do as the holder of the reserve currency.

However, it also quotes JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategist Marko Kolanovic, who argued in a report this week that Trump’s isolationist foreign policy is a “catalyst for long-term de-dollarization.”

Put another way, the dollar is in jeopardy of no longer being the world’s primary reserve currency and enjoying the “exorbitant privilege” that goes along with that, such as interest rates that are lower than they might otherwise be and the government being able to fund budget deficits in perpetuity.

“With the current U.S. administration policies of unilateralism, trade wars, and sanctions increasingly affecting both friends and foes, the question arises whether the rest of the world should diversify away from the risks of the U.S. dollar and dollar-centric finance,” Kolanovic and his team of quantitative and derivatives strategists wrote in a research note.

Buying gold

Bloomberg presents an interesting story of how central banks and other very large institutional investors are slowing their dollar buys amid US dollar strength. But the news service doesn’t go far enough in discovering that, as they’re dumping dollars, central banks are buying gold. We wrote about that last week in Why are central banks buying gold and dumping dollars?

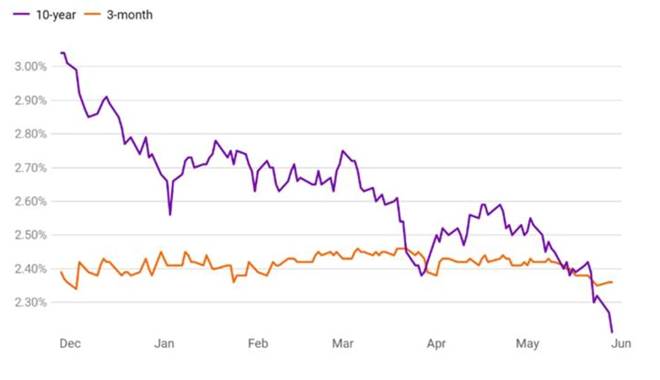

Why are they buying? Gold prices usually go up when real interest rates turn negative, in other words, when interest rates minus the rate of inflation go below zero. While we aren’t there quite yet, taking a look at the 10-year benchmark Treasury yield reveals a rate of interest that has been dropping for some time.

Central banks purchase US Treasuries to bulk up their foreign exchange reserves. They do this especially during periods of unrest, or when the economic forecast is bleak. Gold’s role as a safe haven is well-documented. Of courseTreasuries are as much or more sought-out by investors in a crisis or pending crisis, but lately, Treasuries have become much less popular as a means of storing wealth.

According to the World Gold Council, central banks are continuing a buying spree that started in 2018. A total of 651 tons of gold was accumulated last year, 74% more than 2017 and the highest amount since the end of the gold standard in 1971.

So far in 2019, central banks have squirreled away 207 tons in bank vaults, the highest year-to-date purchases since central banks became net gold buyers in 2010. (before that they were net sellers, selling more gold than purchased).

Awful bond yields

The reason is simple: T-bills don’t offer a good return, and neither do other sovereign debt instruments – five important central banks are currently offering negative rates.

Looking at the 10-year yield chart, we see the yield starting to go down last November, falling steadily all the way to its current 2.02%. Subtract 1.8% inflation and the real yield, just 0.22% begins to look pretty skinny.

There’s an old saying on Wall Street “Six percent interest will draw money from the moon.” And it’s true, but what is also true is 1. As long as real interest rates are below 2% gold is in a bull market and 2. Real interest rates below 2% draws investors to gold.

Central banks know this, so do educated gold buyers.

With Treasury bills paying such low net yields, gold becomes an attractive investment. And while the precious metal offers no yield, its status as an inflation hedge and store of value not subject to fiat currency manipulation are good reasons for central banks to purchase gold.

It doesn’t take an economist to see what’s happening here. Central banks see Treasury yields slumping and real yields low, and likely on their way negative, so they are backing up the truck for gold. They see gold continuing to increase in value.

Danger ahead

Why are Treasury yields falling? Well, the prices of bonds run inverse to their yields, so in times of economic uncertainty, bond investors “dance a little closer to the exits.” They park their money in short-term Treasury bills rather than going long, because they aren’t too confident in the outlook for the US – a $22 trillion debt burden and annual deficits running close to 4% don’t help. This causes the yield curve to invert – meaning the rates for short-term bonds are higher than longer-term bonds, normally it’s the opposite. The yield curve is an extremely accurate recession predictor. In the last 60 years, the yield curve has presaged every recession. The yield curve between the three-month and 10-year Treasury yield has been inverted since mid-May.

A number of other key economic indicators are blinking “caution” for investors.

US unemployment is at record lows but the job numbers are indicating a shift. The country created 75,000 jobs in May, well off the expected 185,000.

The trade war is far more serious than a year ago when the first tariffs, on aluminum and steel, were enacted. Tariffs now encompass over half of the roughly $500 billion in goods that China exports to the US, and almost all American goods imported by China.

Uncertainty over the trade war is having an effect on business leaders who are deferring strategic decisions and in some cases, rejigging their supply chains.

Morgan Stanley reported a rapid deterioration in US business confidence. The investment bank’s gauge of business conditions fell 32 points, the biggest drop since the financial crisis.

The PMIs for US services and manufacturing in May were the worst since recessionary 2009 – adding to the sentiment that US economic growth is slowing.

As for the US Federal Reserve, its board of governors last week sent a strong message that a rate cut is being considered to bolster the flagging economy – a complete 180 from six months ago when the US central bank was looking at further raising interest rates.

Why cut? The Fed is concerned about low global growth, disturbingly weak 1.8% inflation, and a cartload of other signals that we are heading into a recession.

The latest data to support a cut showed first-quarter home sales falling to a five-month low. Consumer confidence slumped to its lowest level since September 2017. The latter is important because consumer spending makes up two-thirds of US GDP.

“Crosscurrents have re-emerged, with apparent progress on trade turning to greater uncertainty and with incoming data raising renewed concerns about the strength of the global economy,” Fed Chair Jerome Powell said Tuesday, ahead of a speech to the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

Why buy a “bund”?

Global tensions such as a war with Iran, the fear of a Brexit hard landing, unresolved trade disputes and anemic global growth, to name just a few problems, are forcing investors into safe havens like government bonds, even though their rates are abysmal.

The dramatic bond rally we are currently seeing, is driving down yields across the world (bond prices and yields move in opposite directions). Investors are piling into sovereign debt based on expectations of new monetary stimulus similar to earlier quantitative easing programs that pushed down interest rates to zero and sparked a global bull market in stocks, that is still going 11 years later.

A lot of the debt being taken on has negative interest rates. Last week, the value of debt being offered at a negative yield increased by nearly $1 trillion. According to Bloomberg, bonds with sub-zero debt yields now make up an astounding 25% of the bond market, and nearly 40% of the sovereign debt market.

Germany auctioned its 10-year “bunds” for the lowest yield on record – negative 0.24%. Quite a fall from the 2.9% rate of interest the bonds commanded in January.

All the uncertainty around Britain leaving the EU has apparently damaged Europe’s largest economy; its manufacturing sector is reportedly heading for a recession.

Purchasers of German debt are almost guaranteed to incur a loss if they hold them until maturity. So why buy them? Fear. The global economic outlook is so scary, they would rather park their money in negative-yielding debt.

Investors are holding their noses and buying bonds now, before rates go any lower. As the Financial Times reported, “highly rated bonds” like Germany’s “bunds” and US Treasuries, “have rallied in recent weeks as concern over the global economy – heightened by the US-China trade dispute – has sparked expectations that major central banks will assume a more dovish posture.”

Reuters points out that reducing interest rates or at least sounding off on the possibilities, is “in vogue at the moment.”

The news service notes that, along with the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of Japan pursuing a dovish monetary policy, so are emerging markets, such as India and Russia which have already started easing. Indonesia, the Philippines and Brazil have flagged interest rate cuts in the near future. Switzerland, Japan, Sweden and Denmark have all gone to negative or near-negative interest rates, to try and spur growth and to stimulate exports.

The monetary doves are clearly in control.

Dumping Treasuries

We started off this article noticing how central banks and other institutional investors have been selling US dollar foreign exchange reserves. This trend corresponds to another related trend we see happening – central banks are off-loading their US Treasuries.

Here’s how the two are related: When a country’s exporters receive dollars for their goods sold to the US, the central bank converts the dollars into its home currency, then places that money into their foreign exchange (forex) reserves. They then plow that forex into a safe haven, US Treasury bills.

March saw a big sell-off of US T-bills held by foreign central banks, due to the factors we’ve outlined – low yields, especially on long-term bonds, and concerns that interest rates are going to fall, further depressing yields.

South China Morning Post notes that in total, overseas investors in March sold a net $12.5 billion in Treasuries and $24 billion in US stocks. Surprisingly, the biggest seller was Canada, dumping $12.5 billion worth of securities, the most since July 2011.

China – by far the largest holder of US Treasuries – in March sold the most in 2.5 years, $20.45 billion, and that was before the United States increased tariffs on $200 billion worth of US-bound Chinese goods from 10% to 25%. It’s possible that Beijing has ordered the sale of more Treasuries as retaliation against US tariffs.

Recall what we said earlier, that central banks are dumping their dollars and buying gold. The Chinese central bank has added to its gold reserves every month of the last six. Since December the People’s Bank of China has expanded its gold holdings by more than 70 tons.

Russia is a dramatic example of central banks getting out of dollars and into other assets. In one year, between September 2017 and September 2018, the Russian central bank sold off over half of its foreign-currency assets denominated in dollars, and “sharply increased the shares of the euro and the renminbi.”

Russia is also the leading buyer of gold. Last year its central bank stocked up on 274 tons of the precious metal, accounting for 40% of central bank buying. Bullion now represents about 19% of its forex, the most since 2000.

As the target of US sanctions, Russia sees diversification from the dollar and into gold and other currencies, as a way of skirting trade restrictions.

It’s also worth mentioning that, as central banks become less weighted with US Treasuries, they are buying more Japanese yen, Chinese yuan and euros. In 2018 the amount of yuan, while only representing 1% of global foreign exchange reserves, doubled from the previous year.

South China Morning Post states that by increasing the share of gold and Special Drawing Rights – the IMF’s composite currency – in its foreign exchange reserves, Chinese media said Beijing was shoring up support to ensure the stability of the yuan.

Race to the bottom

To recap, we have economic indicators not only for the US, but Europe and China, pointing to a recession in the not-too-distant future. The yield curve between short and long-term Treasury yields has been inverting. An inversion has accurately predicted a recession will occur, on average, 14 months later. We also know oil price spikes correlate even more closely to recessions than inversions.

All of this is taking place amid a trade war between the US and China, wherein the US president favors a low US dollar in order to make US exports more competitive, to correct the yawning trade deficit, and restore American manufacturing which has been hit hard by cheaper foreign currencies.

Decades of currency stability, when countries had a “gentleman’s agreement” not to competitively devalue their currencies, may be coming to an end. President Trump has accused China, Russia, Germany and Japan of purposely keeping their currencies low – which is ironic because the US has done the same thing through its rounds of quantitative easing, 2008-15.

Other central banks – Japan and the ECB for example – also employed bond-buying, as well as interest rate cuts – to stimulate their economies, after the damage caused by the 2008-09 recession.

Now, slow global growth, caused partly by the trade war restricting global shipment volumes, as well as a slower Chinese economy, is bringing back dovish policies like interest rate cuts and bond-buying.

Central banks know about the low Treasuries and other sovereign debt yields, some even going negative, and are staying away from them. They’re selling Treasuries and dollars, buying gold, and to a lesser extent, yuan, euros and yen.

If the US insists on pursuing a low interest rate and a low dollar, its trading partners will be forced to follow suit and devalue their currencies, in order to keep competitive, and maintain export levels. Reuters agrees:

The impact of looser Fed policy may be felt around the world through a decline in the dollar, which could pressure Europe and Japan to follow suit to keep their exporters competitive – the makings of the tension over currency that has plagued G20 meetings before.

“It is hard to see how you get a cooperative outcome,” said Vincent Reinhart, chief economist at Standish Mellon Asset Management and a former top staffer at the Fed.

“A trade dispute can become a currency dispute pretty quickly. If what the United States ultimately wants is a depreciation, I don’t see others raising their hands and saying I will take the appreciation … We don’t have many trading partners that are in a position to share weakness.”

This could lead into a dangerous currency war that nobody wants, with every participating country engaging in a race to the bottom in order to out-export, and devalue, its trading partners, who have become adversaries.

Think about what could happen in a trade war between the US and the other countries it trades with. Because the States has the reserve currency, it can simply print more dollars (while keeping an eye on inflation), buy government bonds and issue more Treasuries, thus adding to the already huge $22 trillion mountain of debt. The most important thing though is interest rates and the dollar kept low.

This encourages exporters to make more goods, increasing US GDP. Manufacturing would thrive, and companies would become more profitable. However, this would be at the expense of its trading partners. In the long run, they wouldn’t be able to survive a currency war.

Look at what the US is preparing to do. The Commerce Department has just been appointed new powers that certainly appear to take the fight with China in this direction.

France24 reports on a proposed new rule that allows the United States to impose tariffs on any country it determines is manipulating its currency.

Commerce is being given a wide scope of power to decide whether or not a country is manipulating its currency to the detriment of the United States.

Right now the US Treasury produces a report every six months on whether any country is manipulating their currency to the disadvantage of the United States. A finding of currency manipulation “could impose tariffs to offset the weaker exchange rate against the US dollar,” states France24.

According to the proposal, Commerce said it would defer to Treasury’s evaluation of whether a currency is undervalued, “unless we have good reason to believe otherwise.”

In other words, if Treasury believes from its evaluation, that a country is manipulating its currency, the Commerce Department won’t go any further to investigate. Or at the very least, it’s ambiguous as to what the department would do to prove it. The Treasury’s finding could conceivably be enough to move forward with trade sanctions.

So, not only does the US have more fire power than any other nation in a currency war, it is also arming the Commerce Department with the power to slap tariffs on any currency that devalues, up to the amount of the devaluation. If its trading competitors did the same thing, in retaliation, we could be looking at endless rounds of devaluations and tariffs, that would eventually destroy global trade.

Or, the countries the United States trades with could decide to cut the dollar out completely – stop trading with the US and cease buying dollars/ US Treasuries.

This would mean the end of the US dollar’s exorbitant privilege and its status as the world’s reserve currency. It would most certainly cause a major dislocation of the financial system of the likes never before seen in economic history.

Conclusion

Are we being alarmist? Maybe. But we are already seeing much evidence of de-dollarization in effect. Since the Fed heavily hinted that it would cut interest rates in July, the dollar has fallen 2% in a week.

The US Treasury had to borrow $1 trillion to finance the deficit, the second year in a row that’s happened, by issuing a trillion worth of Treasury bills. This can’t be sustainable. What happens if the leak in Treasury-bill buying turns into a rushing torrent? The United States would be unable to finance its deficit.

We’ve seen central banks, over the last quarter, giving the brush-off to near-negative yielding US Treasuries in favor of bonds that offer higher yields – even risky Greek bonds – and piling into gold, the best safe haven in times of crisis.

And we’ve witnessed more cooperation between Russia and China, through the signing of multi-billion-dollar energy deals and currency swaps that water down the greenback’s influence.

Soybeans are China’s top import from America. A joint venture between Chinese and Russian companies will invest $100 million over three years to build a soybean crusher and grain port in Russia, and lease 247,000 acres of farmland to grow wheat, corn and soybeans. The country is also reportedly building a new port in the northeast that will ship grain harvested in Russia by Chinese companies, as part of its Belt and Road Initiative.

Russia and China have been cozying up in other ways over the past few years. In 2014 Russian state-owned Gazprom signed an eye-popping $456 billion gas deal with China. The year previously, Rosneft agreed to double oil supplies to China in a deal valued at $270 billion, and in 2009 Russian oil giant Rosneft secured a $25 billion oil swap agreement with Beijing.

2014 was also the year that China really started to move away from the dollar. China agreed with Brazil on a $29 billion currency swap in an effort to promote the Chinese yuan as a reserve currency, and the Chinese and Russian central banks signed an agreement on yuan-ruble swaps to double trade between the two countries. The $150 billion deal, one of 38 accords inked in Moscow, is a way for Russia to move away from U.S. dollar-dominated settlements.

The latest evidence of Chinese-Russian business ties involves a new crude oil futures contract, priced in yuan and convertible into gold. The Shanghai-based contract allows oil exporters like Russia and Iran to dodge US sanctions against them by trading oil in yuan rather than US dollars.

At Ahead of the Herd we believe the global economy has reached an inflection point, that is very close to breaking down. Global growth has slowed, compounded by the trade war between the US and China, and fears over what hundreds of billions of tariffs will do. Central banks are worried about economies cooling, witnessed by low inflation, and are looking at monetary stimulus, in the form of interest rate cuts, and/or massive bond-buying programs like we went through with quantitative easing in the US, Europe and Japan.

That worked pretty well after the financial crisis, when the world economy was more or less back on track, with no trade wars and tit for tat tariffs impeding international trade, and the US dollar still carrying enough heft to enjoy exorbitant privilege.

This time is different. We have an unpredictable president in the White House that has already done much damage to the world economy, hurt the relationship between the US and its largest trading partner, and now appears heading towards a currency war wherein the US and China, and likely Europe, duke it out over who can out-export the other. One outcome is a gradual race to the bottom, like a swirling drain. The other is for America’s trading partners to punt the dollar and go with a basket of currencies like Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), possibly backed by gold.

In the meantime, a quote from The Mises Institute, via Zero Hedge, frames pretty well the situation we are in:

Political money will unravel; commodity money will reassert itself. Central bankers will force depositors into the bizarro-world of negative interest rates, destroying capital and dramatically hurting savers. Central bankers similarly will do everything they can to avoid a stock market crash. They will once again buy assets and prop up equities, while telling us their fiat currencies are healthy—even as they quietly buy more gold than they have in decades.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.