Coronavirus and the vulnerability of critical mineral supply chains

2020.02.05

Just in time (JIT) is an inventory system designed to efficiently match raw-material orders with production schedules, in manufacturing and/ or shipping a given product. The idea is to move the precise amount of material into the production process, warehouse or to the customer, ‘just in time” to be used.

Receiving goods only as they are needed reduces the cost of storing excess inventory, and requires producers to forecast demand accurately. This compares to “just in case”, an earlier method of inventory control whereby producers always kept enough inventory to meet periods of high demand.

JIT has become ubiquitous in today’s consumer economy. Examples include car-parts assembly plants; food distribution networks where fresh produce must be grown, stored, refrigerated and transported to maintain peak freshness; container shipping where goods are transported in multiple modes – ocean carrier, train and/or truck – then arrive at a port to be loaded onto a vessel with minimal delay; and Amazon, which revolutionized online commerce through a highly efficient and robotized system of packaged good delivery. Imagine the coordination that goes into an Amazon Prime customer receiving a package ordered the same day.

For most companies, most of the time, JIT works very well, as long as there are minimal disruptions to the chain of supply, all the way from the material in its rawest form, down to the finished product that is delivered to the end user. It is for the most part an efficient, cost-effective, common-sense way to run a business.

Enter a disruption, however, and the average JIT system falls apart quickly, and spectacularly. A good analogy might be a chain-reaction crash on a highway during a snow storm. The damage from one car sliding into a ditch is minimal and easily contained. Add 20 cars all traveling in the same direction not far behind one another, and an accident involving the lead car turns into a multi-vehicle pileup with many people injured and several cars damaged or written off.

When JIT fails, the negative effects on production lines, delivery schedules and especially on a company’s reliability, can have a severe impact on operations and involve a number of unexpected and hidden costs or fees.

Investopedia gives a good example of Toyota’s JIT system coming to a screeching halt in 1997 due to a fire at an auto-parts supplier. The fire decimated Aisin’s ability to produce P-valves. The weeks-long shutdown at Aisin caused Toyota to halt production for several days. However the worst part was the ripple effect. Because Toyota relied on P-valves at a certain point in the assembly process, all the other Toyota parts suppliers also had to shut down because the automaker couldn’t use their parts during that same period. The fire consequently cost Toyota 160 billion yen ($) in revenue.

Covid-19 and JIT

Over the past couple of months we have been reading regular news reports about how the new coronavirus, Covid-19, has impacted supply chains. No surprise, considering that China, the epicenter of the outbreak, accounts for 35% of global manufacturing output, has been the world’s largest goods exporter since 2009, and in 2013 became the world’s biggest trading nation. Arguably, considering China’s heft in the world economy, the coronavirus outbreak couldn’t have happened in a worse country.

Economic fallout from Covid-19 continues to worsen. On Monday Oxford Economics downgraded China’s annual growth projections this year to 4.8% – the worst in decades. The OECD issued a report saying that the outbreak could ding global economic growth by half a percentage point, putting it at 2.4%, in a best-case scenario. (global growth last year was 2.3%, the worst in a decade)

Market fear around the coronavirus has sunk the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond to new lows, as investors flock to the safety of Treasuries (and gold), raising their prices and causing yields to plummet. On Tuesday the yield on the benchmark 10-year note dropped to an all-time low of 0.906%. Subtracting 2.5% inflation from leaves a net negative yield of – %. When yields are under 2% investors look at getting out of money-losing bonds into gold, which last year gained 18%.

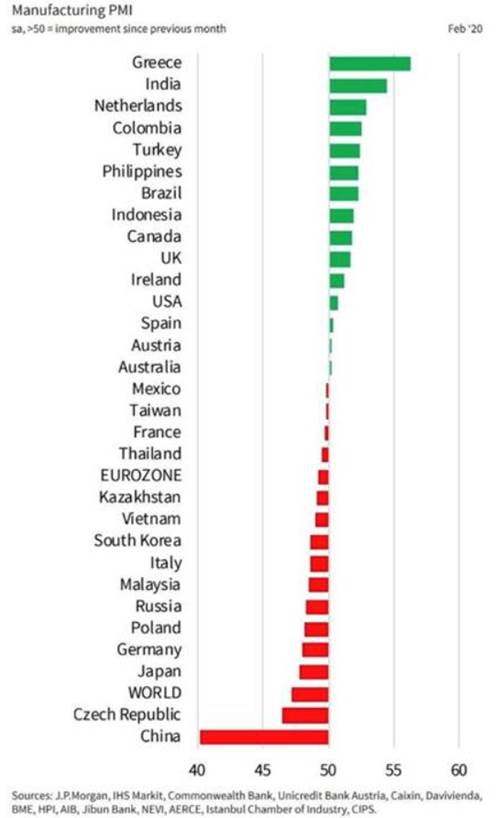

Over the weekend China’s PMI manufacturing data sunk to 35.7 (the services PMI was even worse at 28.9), against expectations of 45. (PMIs under 50 represent an economic contraction)

PMIs not only in China have been seriously whacked due to the virus’ impact on supply chains. According to Zero Hedge the global manufacturing sector has suffered its steepest contraction since 2009. Out of 31 nations for which data was available, 15 saw their output contract. They include China, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, South Korea and Australia.

If Chinese manufacturing falls off a cliff, like it appears to be doing, then a number of supply chains will be affected including critical minerals. If and when the virus reaches the level of a pandemic and Beijing is forced to wall the country off from all but the most necessary imports, metals critical to the economic and military security of the United States could be affected including rare earths used in dozens of defense applications including missile guidance systems, permanent magnets, wind turbines, electric vehicles, etc., as well as the materials required for the building of EV batteries – lithium, graphite, nickel, cobalt, manganese.

As we all know, China has a lock on most of these materials and if supply chains are cut due to quarantines, port closures, sick employees, etc., the effects on end users could be devastating.

In a recent article Fastmarkets reported how the coronavirus has closed factories and left them operating at reduced capacity or struggling to receive and send parts.

As suggested, above, The knock-on effect has been swift. Toyota Motors, for instance, has said that its operations in Japan might be affected by the virus since some plants in the epicenter of the outbreak in China still can’t operate or transport goods.

In a highly unusual method of exporting its products, Jaguar Land Rover flew car key fobs out of China in suitcases. Apple, meanwhile, has said it will miss its revenue outlook because of manufacturing constraints on the iPhone, which is mainly produced in China.

In the world of commodities, global mining giant Rio Tinto has said it expects short-term impacts to supply chains and potentially from services from Chinese suppliers as the country gets to grips with the crisis.

The publication wisely notes, If trade wars had helped spur diversification trends, then the virus is being viewed as yet another reason why alternative suppliers might be a good idea.

Lots more on that below but for now, feast on some facts by Information Clearing House about how the dangers of world-wide out-sourcing and globalization have come back to bite.

The article by F. William Engdahl states that 80% of medicines consumed in the United States are made in China. Among them are most antibiotics, birth control pills, blood pressure medicines such as valsartan, blood thinners such as heparin, and various cancer drugs. The list also includes medications to treat HIV, Alzheimer’s disease, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, depression and epilepsy,

Even over-the-counter remedies like Vitamin C have been outsourced to China, able to produce them much cheaper than in the West.

Imagine what could happen if factory closures or limited operations start restricting drug shipments, leading to shortages in the pharmacies of Europe and North America?

Engdahl quotes Rosemary Gibson of the Hastings Center bioethics research institute, who wrote a book on the topic, saying that “…if China shut the door tomorrow, within a couple of months, hospitals in the United States would cease to function.”

The passage is worth quoting in full:

At the time the outsourcing of US and European drug manufacture to China began no one could imagine the present health catastrophe growing out of Wuhan in a matter of days. The massive China quarantine since late January has shut some 75-80% of all Chinese factories and created an unprecedented domestic China demand for every kind of medical product since the WHO declaration of medical emergency around the coronavirus or COVID-19 events at the end of January. It is unclear how badly deliveries of vital pharmaceuticals including essential antibiotics from China to the USA or Europe or other countries will be affected though anecdotal reports of hospitals beginning to experience delivery problems are surfacing. Even the idea to turn to India, another major global pharmaceutical supplier, only finds that most Indian manufacturers are dependent on China for their active drug ingredients.

Returning to the topic at hand, we note that China has lost an estimated 4 million barrels a day of oil demand, compared to 5 Mbod in 2008-09, and that 45% of container vessel sailings from Europe to Asia were canceled in the four weeks following Chinese New Year.

“The production system is also more vulnerable than at the time of the Spanish Flu. The global economy today is reliant on extremely long and complicated supply chains, with many goods being produced from components manufactured in dozens of countries, and shipped between them on container vessels. If manufacturing in even one place (such as China) comes to a near standstill, production elsewhere will do the same. “Just in Time” manufacturing methods will run out of inputs, even if their factories are still capable of operating. Shipping could be affected if, crews refuse to undertake trips that can take weeks with potentially asymptomatic carriers on board, or if crews are quarantined for two weeks prior to departure.” Prof Steve Keen

BHP, the world’s biggest miner, on Tuesday warned that demand for oil, copper and steel could slide unless the epidemic is contained soon. “If the viral outbreak is not demonstrably well contained within the March quarter, we expect to revise our expectations for economic and commodity demand growth downwards,” the company said in a statement.

EVs and wind

Among the sectors most affected are electric vehicles and wind energy.

Coronavirus has already cut into production of battery storage by 10%, given that Hubei, where the virus originated, and surrounding provinces are responsible for 60% of China’s battery cell production.

Metal Bulletin reports that disruptions to Chinese exports could tighten the supply of processed lithium, especially in Japan and South Korea. China has three-quarters of the world’s lithium-ion battery manufacturing capacity, and 50% of the world’s public vehicle-charging infrastructure.

The publication, known for its critical metals coverage, is expecting China’s demand for imported battery raw materials to fall, causing an increase in stockpiles in South America and Australia where the majority of the world’s lithium is mined.

Demand for electric vehicles in China is also expected to suffer, as household and business confidence deteriorates, in the short term. European OEMs that rely on lithium battery cells from Asia may see supply chain interruptions that could hit EV manufacturing – there may even be a pick-up in demand for non-Chinese production of battery cathode materials.

Not everyone is aware that China has the most wind power capacity in the world. Yet fewer wind turbines are likely to be manufactured from China in the first quarter, owing to the coronavirus. According to energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, virus-related production delays, compounded by already tight supply of key components such as turbine blades and main bearings, have already reduced output of those components by about 10%. The fallout may also be felt in the US, where installation of wind turbines could be stalled, putting at risk 6 gigawatts of scheduled wind power capacity, Fortune reported.

Lithium and rare earths

Things were tough for lithium producers even before the onset of Covid-19. The two largest lithium miners, US-based Albemarle Corp and Chilean state-owned SQM, both reported a drop in fourth-quarter earnings.

Albemarle posted Q4 net income of $90.4 million compared to $129.6 million in the year-ago quarter, while SQM said its profit in the last quarter trailed nearly 38% – at $66.9 million versus $108.6 million.

The Charlotte, North Carolina-based company produces lithium in Chile and Australia and sends it to China for processing. However on Feb. 20 Albemarle said it is utilizing only 25% of its lithium production capacity in China, owing to slack demand and the coronavirus.

Over in Chile, SQM predicted its sales volume to China during the first quarter will come in below expectations.

Turning to rare earths, several processing facilities remain closed after the Chinese New Year holiday in February, and there have been disruptions to local and national transportation networks and labor availability, according to a recent report by Roskill.

“While temporary closures are not uncommon around Chinese New Year celebrations, the widespread prolonged nature of the closure, compounded by disruption to distribution networks, has caused concerns over the supply of Chinese rare earths both domestically and internationally,” Roskill’s David Merriman wrote.

As of February, Merriman’s report found an estimated 70-80% of capacity had been suspended for a period, representing between 80,000 and 100,000 tonnes per year of rare earth oxides – predominantly the more valuable heavy rare earths – out of the 173,000 tonnes of REO production in 2019.

Production at some rare earth processing facilities in China’s southern provinces has been restarted.

Meanwhile truck drivers are reportedly refusing to make deliveries into areas suspected of harboring the disease, which has interrupted not only the flow of minerals but of chemical reagents necessary for refining rare earths and producing metals, alloys and magnets.

The Global Times, a daily tabloid run under the auspices of the Chinese Communist Party, in February quoted the manage of a large, state-owned magnet producer saying that most upstream and downstream rare earth companies in the city of Ganzou, a rare earths hub, had not restarted work due to the lack of local labor.

The Association of China Rare Earth Industry said if production does not resume within a month, it would affect rare-earth exports to the US, Japan and Europe and weigh on global supply chains.

In a contributing column to Investorintel, rare earths expert Jack Lifton notes the dependence of US and European manufacturing on the Chinese rare earths supply chain. Its just-in-time nature means companies maintain limited or even zero inventories, making them vulnerable to a supply disruption – particularly for Rare earth enabled components for moving machinery, such as automobiles, trucks, trains, aircraft, industrial motors and generators, home appliances, and consumer goods, almost all today come from China or Japan (which of course get its rare earth magnets, alloys, phosphors, and catalysts from China). That flow is now slowing. This will have a domino effect on American and European industry. These items cannot be re-sourced due to China’s monopoly of rare earths production and its monopsony of rare earth enabled component manufacturing.

Indeed the outbreak has highlighted concerns about the dependence of the United States, Europe, Japan and Australia on Chinese rare earths refiners.

Jack Lifton writes: There is an urgency now for the creation of a total domestic rare earth end-use products supply chain in the USA, Europe, and non-Chinese Asia.

Even before the outbreak (in November 2019) Australia and the US were moving towards that goal through a partnership developing critical minerals supply chains including rare earths. Japan wants to halve its rare earth imports from China by 2025 and is in talks with the US and Australia on a cooperation deal, according to Stockhead.

On Jan. 9, Canada and the United States announced the Canada-US Joint Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration, to advance “our mutual interest in securing supply chains for the critical minerals needed for important manufacturing sectors, including communication technology, aerospace and defence, and clean technology,” reads a press release from Natural Resources Canada.

The announcement follows a June 2019 commitment by Prime Minister Trudeau and President Trump to collaborate on critical minerals.

The Covid-19 outbreak certainly puts a laser-like focus on insecurity of lithium and rare earths supply for North America, especially in light of the fact that several battery companies and EV automakers are planning on setting up shop in the United States. If and when they do, they will need a ready supply of raw materials, the majority of which must currently be sourced in China.

US mine to battery to EV supply chain

A Reuters analysis shows that automakers are planning on spending a combined $300 billion on electrification in the next decade.

Opened in 2016, Tesla’s Gigafactory in Nevada is a going concern. Every day 1,000 cars sets are trucked from the Gigafactory to an assembly plant in Fremont, California. The three-storey structure, the size of a dozen football fields, has 13,000 people working for Tesla and its Japanese battery partner, Panasonic.

GM rolled out its 2020 Cadillac SUV, built in Spring Hill, Tennessee, in a move designed to challenge Tesla.

In 2017, coinciding with its 20th anniversary, Mercedez-Benz announced plans to set up an electric car production facility and battery plant at its existing Tuscaloosa, Alabama plant. The $1-billion expansion will include a new battery factory near the production site, with the goal of providing batteries for a future electric SUV under the brand EQ. Six sites are planned to produce Mercedes’ EQ electric-vehicle family models, along with a network of eight battery plants.

Volkswagen has said it will invest $800 million to construct a new electric vehicle – likely an SUV – at its plant in Chattanooga plant, starting in 2022. For more read Volkswagen to drag Tesla, making EVs in Tennessee.

Korean company SK Innovation has said it will invest US$1.6 billion in the first electric vehicle battery plant in the United States, and is considering plowing an additional $5 billion into the project, planned for Jackson County, Georgia.

Meanwhile more battery factories are being built, driven by the demand for lithium ion batteries which is forecast to grow at a CAGR of over 13% by 2023.

All of this explosive growth in battery plants and EVs will mean an unprecedented demand for the metals that go into them. This includes lithium, cobalt, rare earths, graphite, nickel and copper. Lithium for example is expected to see a 29X increase in demand according to Bloomberg.

How will the United States obtain enough lithium for the electric-vehicle storm of demand that is brewing?

The US only produces 1% of global lithium supply and 7% of refined lithium chemicals, versus China’s 51%. The country is about 70% dependent on imported lithium.

To lessen US lithium dependency will require the building of a mine to battery to EV supply chain in North America.

The first step is to develop new North American lithium mines.

Currently the only US lithium producer is chemicals giant Albemarle. Lithium products from Albemarle’s Silver Peak lithium brine operation in Nevada are sent to its processing plant in North Carolina. This material is then loaded on ships and sent to Asian battery manufacturers, which sell the batteries to automakers.

According to Visual Capitalist, Silver Peak only produces 1,000 tonnes per year of lithium hydroxide, within a current lithium market of roughly 300,000 tonnes per annum of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE), a term that encompasses both lithium hydroxide and carbonate used in EV batteries.

Cypress Development Corp (TSX.V:CYP, US:CYDVF)

Three and a half years ago Cypress Development Corp began prospecting in the Clayton Valley, Nevada, hoping to find a property that could support a lithium carbonate resource to compete with or possibly complement its neighbor, Albemarle’s Silver Peak Mine, whose lithium brine grades are declining. Cypress wasted no time in acquiring two land packages located in Esmeralda County: the 1,520-acre Glory property and the 2,700-acre Dean property.

Its Clayton Valley Lithium Project hosts an indicated resource of 3.835 million tonnes LCE (lithium carbonate equivalent) and an inferred resource of 5.126 million tonnes LCE. The project is ranked among the largest in the world.

Last year Cypress Development Corp completed the first two phases of a prefeasibility study (PFS) at its Clayton Valley Lithium Project in Nevada – confirming that lithium can be acid-leached and extracted at high enough recovery rates (84-86%), and successfully separating the lithium-rich claystone ores from the sulfuric acid leachate.

It’s a major technical problem to separate ultra-fine clay particles (<5 microns) from a leach solution. Cypress has done it, putting the company at the forefront of lithium clay projects globally.

The US now has a major source of lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide and potentially a not inconsiderable amount of rare earths and scandium.

According to the PEA Cypress has a unique and potentially extremely lucrative opportunity to mine rare earths at its Clayton Valley Lithium Project. REEs were detected in leach solutions ranging from 100 to 200 parts per million (ppm). The rare earths include scandium, dysprosium and neodymium, in order of economic value.

The long-awaited prefeasibility study, expected out in a few weeks, is crucial to moving the project forward, not only for proving that the metallurgical process for separating lithium from clays is commercially viable, but demonstrating that Cypress’ costs are in line with its 2018 PEA.

The report will come with an extra layer of certainty/ derisking, because it will have not only bench-scale but commercial-sized bulk sample test results. This data will be extremely valuable to a potential joint-venture partner or a company considering an outright buyout of the company.

Cypress Development Corp

TSX-V:CYP Cdn$0.20 2020.02.29

Shares Outstanding 90,077,001m

Market cap Cdn$18,015,400m

CYP website

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Richard owns shares of Cypress Development Corp. (TSX.V:CYP).

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.