Copper shortage narrative goes mainstream

2021.03.12

Mainstream media and the large mining companies are finally catching on to what we at AOTH have been saying for the past two years: the copper market is heading for a severe supply shortage due to a perfect storm of under-exploration/ lack of discovery of new deposits, clashing with a huge increase in demand due to electrification and decarbonization.

Dramatic price rise

Copper is trading over $4.00 a pound this year on rapidly tightening physical markets, rebounding economic growth especially in China, the top metals consumer, and the expectation that the era of low inflation in key economies may soon be over.

Rising more than 22% in 2020, copper had its best year since 2017, with prices boosted by hopes for “green” stimulus (the red metal is an important component of electric vehicles and renewable energy systems. The United States, EU and China have all promised trillions worth of green infrastructure spending), the global 5G build-out, China’s recovery from the coronavirus, and virus-related supply disruptions in top copper producers Chile, Peru and Mexico.

“This current price strength is not an irrational aberration, rather we view it as the first leg of a structural bull market in copper,” Goldman Sachs analysts said in December, with the investment bank raising its 12-month forecast to $9,500 a tonne, or $4.30/lb.

On Feb. 22 copper futures hit $4.12/lb, nearly double the March 2020 low, and approaching an all-time high set in 2011. Copper for May delivery closed at $4.14/pound on Thursday at the Comex in New York.

On the spot market, the base metal has advanced 17% year to date, and its run is likely far from over. Reuters quotes the chairman of Chinese metals trader Maike Group, saying that copper will surge to an all-time high over the next 12 months, as a result of strong demand from China’s clean energy drive and years of under-investment in global mine supply.

He Jinbi, who founded Maike in the 1990s, believes as top consumer China builds metals-intensive renewable energy and electric vehicle infrastructure, copper and other base metals will see serious supply deficits in the future and be subject to capital inflows.

“The market will gradually accept it, because with the recovery of the global consumption market there will also be a shortage of copper in the European and American markets,” he said.

“Global investment in mineral resources “has been seriously inadequate in the past five years,” Jinbi told Reuters.

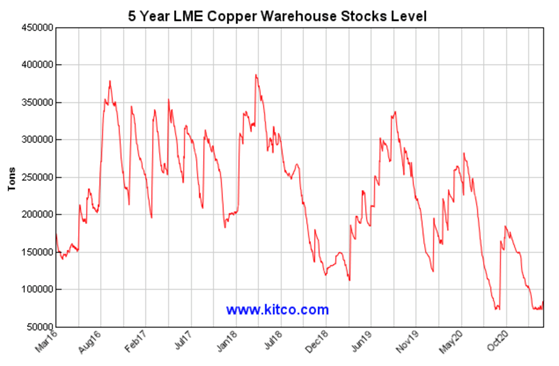

Frenzied copper buying is reflected in plummeting inventories, as the 5-year LME copper warehouse stocks level chart shows.

‘Future-facing metals’

Some of the world’s largest copper companies are doing everything they can to expand existing mines and acquire prospective new deposits, as they seek to replace their rapidly depleting copper reserves and resources.

In 2017 the Chilean government approved a $2.5 billion expansion of BHP’s Spence copper mine – the diversified miner’s second largest copper mine behind Escondida, the biggest copper operation in the world.

That followed closely behind BHP’s 2016 decision to raise its annual exploration budget by 29%, allocating nearly all of its $900 million budget to finding new copper and oil deposits – two commodities the world’s largest miner thinks it needs to bolster future growth. Potential acquisition targets include copper deposits in Peru, the US, Canada, and South Australia.

In February of this year chief executive Mike Henry said the company needs more “future-facing metals” such as copper. Last year, BHP became the top shareholder in SolGold, an Australian miner developing the Cascabel copper-gold project in Ecuador.

Recently BHP announced it is ramping up work on the Spence mine expansion, to reach its production objective in the first half of 2021 (the project has been delayed due to covid-19 restrictions).

BHP is planning to “go green” at Spence, with a focus on running the operation entirely on renewable energy by 2022. The Melbourne, Australia-based company also aims to stop drawing water from aquifers in Chile by 2030 — a reference to the problems mining companies are facing getting enough water in the bone-dry Atacama desert of northern Chile, the base of operations for several major copper and lithium mines.

The $2.5 billion expansion contemplates a concentrator plant to increase production and extending the life of the deposit by about 20 years.

BHP’s latest signal it is getting serious about finding more copper, and fellow “green” metal nickel, is the announcement it is moving its 50-person exploration team from Santiago, Chile to Toronto, to be closer to its main markets.

This week during a speech at the annual PDAC mining conference, BHP’s chief technical officer Laura Tyler said nickel production would have to expand four-fold to meet demand for electric and hybrid vehicles, while copper output also must grow exponentially to fulfill demands for EVs, battery storage, charging stations and power grid infrastructure.

BHP’s headquartering of exploration in Toronto fits with statements being made by Canadian officials who are talking up Canada as a hub for clean-tech metals.

“Canada offers renewably generated electricity, a skilled workforce, a stable and predictable jurisdiction to operate in, the rule of law — a commodity very much in demand these days – and an abundance of the critical minerals needed for the batteries that power electric vehicles,” Francois-Philippe Champagne, the federal Minister of Innovation, Science, and Industry said Canada, said on Wednesday.

BHP is not the only large mining firm taking a serious look at copper. Barrick Gold is interested in diversifying into the red metal from the yellow. CEO Mark Bristow sees Indonesia’s Grasberg, the second largest copper mine in the world, as a potential buy-out target for Barrick. The company already owns the Porgera mine in Papua New Guinea, which borders Indonesia to the east, with China’s Zijin Mining.

Another big gold miner, Newmont Corp, this week announced it has struck a deal with GT Gold, to take over the junior and its Tatogga gold-copper discovery in the Golden Triangle of northwestern British Columbia.

Denver-based Newmont said it agreed to buy 85% of the shares in GT Gold it does not already own, for $3.25/sh, or about C$393 million.

Meanwhile the CEO of Anglo American, another major diversified miner, has indicated that South Africa would be a good jurisdiction to explore. “We are already in Zambia and other places, we want to do more in South Africa, so we are looking for adjustments in legislation there,” Mark Cutifani said during the 2020 Joburg Mining Indaba conference.

Copper, nickel, lead, and zinc are among the base metals Anglo American is focusing its global discovery strategy in greenfield and brownfield projects.

Running out of ore

Why are major mining companies so intent on securing new supplies of copper? Quite simply, they are running out of ore.

As we have reported, without new capital investments, Commodities Research Unit (CRU) predicts global copper mined production will drop from the current 20 million tonnes to below 12Mt by 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15Mt. Over 200 copper mines are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

Some of the largest copper mines are seeing their reserves dwindle; they are having to dramatically slow production due to major capital-intensive projects to move operations from open pit to underground.

Grasberg in Indonesia, the world’s second largest copper mine, is emblematic of the problems copper miners are facing. The mine began as a large open pit but after decades of extracting the easy-to-reach ore is gone and future production is expected to come from a deep cave deposit known as the Deep Mill Level Zone. Copper concentrate exports have plunged dramatically as operations shift from open pit to underground.

Major South American copper miners have also been forced to cut production. State-owned Codelco has said it will scale back an ambitious $40-billion plan to upgrade its mines over the next decade. The world’s largest copper company also said it will reduce spending through 2028 by 20%, or $8 billion.

Chuquicamata is expected to see a 40% fall in production by 2021. A $5 billion expansion, moving from open pit to underground, will take five years to reach full output of 300,000 tonnes per annum — this is not new production.

Shipments from BHP’s Escondida mine took a hit in 2019 due to operations moving from open pit to underground. The largest copper mine on the planet is expected to take until 2022 to re-gain full production, again not new production.

These cuts are significant to the global copper market because Chile is the world’s biggest copper-producing nation — supplying 30% of the world’s red metal. Adding insult to injury, for producers, copper grades have declined about 25% in Chile over the last decade, bringing less ore to market.

Low pipeline

What about new copper mines? Surely mineral exploration companies are identifying new ore bodies, cueing up the next generation of copper producers?

Well, they are trying. Problem is, they are having to go further afield and dig deeper to find copper at the grades needed to economically produce copper products for end users. This usually means riskier jurisdictions that are often ruled by shaky governments with an itchy trigger finger on the resource nationalism button. All the low-hanging copper “fruit” has been picked. Combine that with production problems and you have the makings of a supply shortage.

In fact, new supply is concentrated in just five mines – Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC. And while these mines are expected to account for 80% of base-case output increases until 2022-23, their profitability depends on the copper price staying above $5,000 a tonne, according to analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

The current copper pipeline is the lowest it has been in a century, and not improving. After the delivery of first copper from Cobre Panama (285-310,000t per year), BMO does not see the next batch of +200,000-tonnes projects until 2022-23 — “when the likes of Kamoa (501,000t per year), Oyu Tolgoi Phase 2, and QB2 (316,000t per year) are likely to offer meaningful supply growth.”

Demand drivers and shortfall

Copper’s widespread use in construction wiring & piping, and electrical transmission lines, make it a key metal for civil infrastructure renewal.

The continued move towards electric vehicles is a huge copper driver. In EVs, copper is a major component used in the electric motor, batteries, inverters, wiring and in charging stations. An average electric vehicle contains about 4X as much copper as regular vehicles.

According to the Copper Development Association (CDA) a high-speed train required 10 tonnes of copper components, plus another 10t in the power and communication cables per kilometer of track. Even the most basic gasoline-powered passenger car requires a kilometer of copper wiring, and between 15 and 28 kilos of copper, depending on its size. A traditional internal combustion engine cannot be built without 23 kg of Cu.

It is not only the copper required for EVs but charging stations and charge points. A Level 2 charging station requires 7 kg of copper, a direct current fast charger (DCFC) or Level 3 station uses 25 kg.

BloombergNEF forecasts by 2040 there will be a need for 12 million charge points, each requiring about 10 kg of copper. The number of charging stations recently passed the one million mark.

The latest use for copper is in renewable energy, particularly in photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines.

The Biden administration has promised a $2 trillion clean energy plan, to decarbonize American electricity in 15 years and create a net-zero-emissions economy by 2050. Renewable energy projects left on the shelf by the Trump administration, such as offshore wind developments in the northeastern US, could eventually see the light of day.

Among the details of Biden’s plan for a so-called “clean energy revolution,” are the following:

- Aggressive methane pollution limits for new and existing oil and gas operations.

- Develop rigorous new fuel economy standards aimed at ensuring 100% of new sales for light- and medium-duty vehicles will be zero emissions and annual legislation that, by the end of his first term, puts us on an irreversible path to achieve economy-wide net-zero emissions no later than 2050. The legislation must require polluters to bear the full cost of the carbon pollution they are emitting.

- Invest $400 billion over 10 years, as part of a broad mobilization of public investment in clean energy.

- Cut in half the carbon footprint of US buildings and deploy more than 500,000 new public charging outlets by the end of 2030.

An important part of the shift away from fossil fuels and the aging electricity grids they feed into, is the “smart grid”. Smart grids use technology that make energy integration easier and allow for a higher penetration of renewable energy. They are deemed essential for accelerating the use of fully electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids, and for storing energy from wind and solar installations.

The adoption of smart grid technology in developed and developing countries will boost demand for copper strips used in switchgear, devices that protect equipment and circuits from power spikes. Copper is the conductor material used in transformer windings, strips and busbars. Both power and distribution transformers use copper strips.

The base metal is also a key component of the global 5G buildout. Even though 5G is wireless, its deployment involves a lot more fiber and copper cable to connect equipment.

A report by Roskill forecasts total copper consumption will exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization, and electricity demand. Total world mine production in 2020 was only 20Mt. In many countries it takes 20 years to go from discovery through permitting to mining.

The upshot? There will not be enough copper for future electrification and energy needs, without a massive acceleration of copper production worldwide.

We have already explained the reasons, higher up in the article, for tighter copper supply. But the evidence keeps mounting, and our argument regarding a future copper reckoning is strengthened, as related developments are reported.

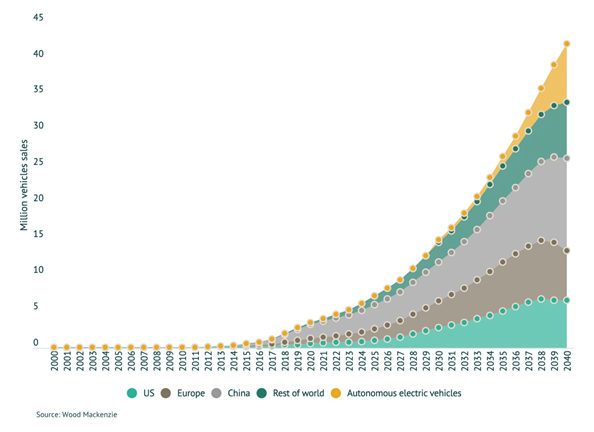

Take, for instance, a recent report by Wood Mackenzie. In its electric car forecast to 2040, the commodities consultant finds EV sales are expected to reach 45 million units per year in the next two decades, with a total global EV stock of 323 million.

For perspective, global EV sales in 2019 were only 2.1 million, with a stock of 7.2 million EVs, according to Global EV Outlook 2020.

Major automakers have set their sights on being climate neutral by 2050 and they view battery electric vehicles (BEVs) as the best way of achieving that target. Change is being driven, pun intended, by stricter vehicle emissions regulations.

While some may scoff at the wild predictions, progress is being made, according to Woodmac, on the obstacles to higher EV penetration.

“The projected price of battery packs keeps dropping. We expect the US$100/KWh threshold to be breached by 2024, one year earlier than our previous projections,” says Ram Chandrasekaran, Wood Mackenzie principal analyst.

“Cumulative residential and public charging points are projected to grow to 32.5 million and 5.4 million outlets by 2030 and will have an investment value of US$2.7 billion and US$3.3 billion, respectively,” said Chandrasekaran.

Europe surpasses China

In Europe, which for decades has led North America in protecting the environment, including recycling, public transit and fewer cars, EVs are taking showrooms by storm.

Last year for the first time, Europe sold more battery-electric and plug-in-hybrid EVs than China, with Germany and France leading the way.

According to the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (EAMA), EV registrations in the EU, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and the UK surged to 1.36 million compared to 560,000 in 2019. That was despite a 20% slump in passenger vehicle sales owing to covid restrictions at car assembly plants, and a semiconductor shortage.

The jump in electric vehicle registrations during the second half of 2020 meant a 175% increase in the watt-hours of batteries deployed, according to Adamas Intelligence.

In Europe, the amount of cobalt in batteries increased 205% compared to H2 2019, there was a 192% increase in battery lithium, and nickel put into batteries rose by 135%.

Globally, the amount of lithium deployed in newly sold vehicles jumped 96%, to 57,300 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent, over the same period. Nickel and cobalt deployed in world battery production during H2 2020 climbed 69% and 85% respectively, according to Adamas.

Europe’s push for more EVs has had a dramatic impact on the prices of battery metals.

Standard-grade cobalt in Rotterdam has risen by 30% and the China price of lithium carbonate, used in lithium-ion battery cathodes, is up a whopping 70% since the start of the year. Nickel last month hit a 7-year high of $20,110 per tonne.

According to BloombergNEF, demand for Class 1 nickel is expected to out-run supply within five years, fueled by rising consumption by lithium-ion electric vehicle battery suppliers. Nickel’s inroads are due mainly to an industry shift towards “NMC 811” batteries which require eight times the other metals in the battery. (first version NMC 111 batteries have one part each nickel, cobalt, and manganese).

As we have written, the combination of structural deficits, pent-up demand, and infrastructure build-outs, are the perfect storm for nickel and graphite.

Strained power grids

Rarely is there a connection made between electrification/ decarbonization, and the source of the new electricity. Where is it all going to come from? Reuters makes the point with alarming precision in a recent article titled ‘EV rollout will require huge investments in strained US power grids’.

The Power Systems Engineering Center at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) estimates that, by 2050, the electrification of transportation and other sectors will require a doubling of US generation capacity.

This is since the goal is to power electric cars with renewable energy, which requires battery storage, rather than the current mix of coal and natural gas. Reuters states:

More electric cars will require both charging infrastructure and much greater electric-grid capacity. Utilities and power generators will have to invest billions of dollars creating that additional capacity while also facing the challenge of replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy sources.

The amount of charging infrastructure required, and additional grid capacity, is bound to demand millions more pounds of copper.

The problems with the current US power grid were thrust into the spotlight during the recent deep freeze in Texas, the extra load on the system causing widespread blackouts.

Conclusion

Piecing everything together, it is obvious that the world copper supply, if it isn yet, will soon be in deep trouble without a push among the large copper miners to find and produce more of the red metal to replace rapidly depleting reserves.

It is a question of basic supply and demand.

Unlike the previous super-cycle, which depended on China, the next structural bull market for commodities will be driven by spending on green energy and transportation, for which copper is a critical ingredient with no substitutes.

As we discovered while researching a recent article, even with a 30% penetration of EVs, a relatively conservative estimate, we need to find another 20 million tonnes of copper per year over 20 years. And we will still need enough copper for all its other uses, in construction wiring & plumbing, infrastructure build outs, electrical grids, energy storage, 5G, etc.

A goal like that is not insurmountable, but it will take major investments in copper exploration, at a scale that has never before been attempted. Any copper junior with a deposit of significant size and grades, will have no problem attracting a major or mid-tier acquirer, that can help finance a future copper mine and bring it to commercial production.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.