Copper price drivers

2019.12.17

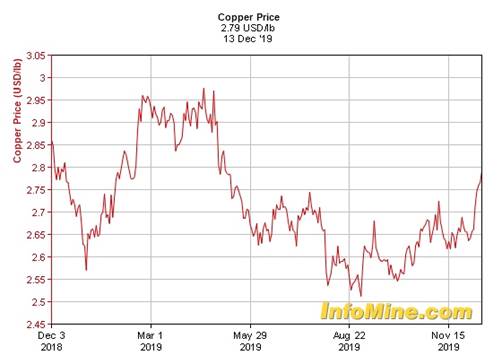

The copper price was holding steady at $2.79 per pound, Monday, just four cents shy of a seven-month high ($2.83/lb) reached Friday, on news of a partial trade deal reached between the United States and China.

Copper’s sensitivity to economic growth levers has earned its “Dr. Copper” moniker. Because copper is used in a number of sectors – construction (plumbing, wiring), communications, power distribution and transportation – prices rise and fall on expectations of future demand. It is a leading indicator of economic output.

Looking at a one-year chart, copper has had a rip-roaring fourth quarter. From its 52-week low in August of $2.51 a pound, the base metal has gained an impressive 11%, reaching a pinnacle of $2.83/lb last Thursday, on expectations of a trade war resolution between the world’s number one and two economies, and the improved economic growth prospects that would entail. Copper has risen 7% in December alone.

China is the world’s top copper buyer, consuming around half of global shipments. Last year it imported a record 5.3 million tonnes of refined copper. Recently, imports of unwrought copper hit their highest levels since September 2018.

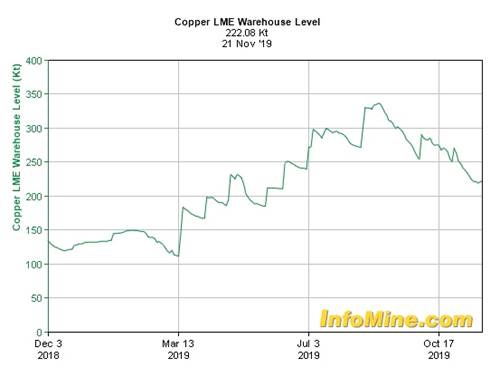

But the dispute with the US has weighed on prices, not only of copper but other base metals such as iron ore and zinc, for over a year, even as warehouse inventories drop and there is a chronic under-investment in new mines to replace depleted mineral reserves.

Trade deal promise

On Friday, Chinese officials agreed to billions worth of US agricultural products, in exchange for an American promise not to hit China with another $160 billion worth of tariffs, that would have come into effect last Sunday, Dec. 15.

Instead the United States will keep the 25% tariffs on $250 billion of Chinese imports but will reduce levies on $120 billion in products from 15% to 7.5%, CNBC reported. The trade war has lasted 18 months and without a resolution, it looms over the 2020 presidential election, making the Trump administration eager for a deal.

US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer said on Sunday that the first-phase deal is “totally done” and will nearly double exports to China over the next two years.

Most market observers believe that a complete trade war resolution will be very good for commodities, including metals, energy, agricultural products and industrial inputs like iron ore, coking coal and steel. Mining analyst Dave Forest of Casey Research writes that “The end of the trade war will be a huge catalyst for commodities.” I tend to agree.

The fundamentals of copper, zinc and lead for example are all extremely bullish, yet the prices of each have languished as the trade war drags on. Investors of mining stocks and physical metals don’t know what’s coming next, so they’ve stayed on the sidelines, waiting to see what happens.

Now, with a phase-one trade deal in hand, things are looking up for metals, in a big way. Forest states, and I agree with him,

Once the trade war’s over, it’ll be off to the races for these key metals. Investors will be euphoric about the global economy again. Combine that 180-degree turn in sentiment with strong fundamentals for metals like copper – and you’ve got an explosive setup.

Output cuts

What does he mean by strong fundamentals? Well, the base metal is heading for a supply shortage by the early 2020s; in fact the copper market is already showing signs of tightening – something we at AOTH have covered extensively.

As we wrote in The coming copper crunch, over 200 copper mines currently in operation will be depleted in the next 15 years. Without new ones to replace them, we are looking at a 15-million-tonne supply deficit by 2035.

Exacerbating falling inventories, and copper market tightness, smelting companies have slashed the prices they charge mining companies to process copper ores – wanting to absorb as much supply as they can.

Supply is already tightening owing to events in Indonesia and South America, where most of the world’s copper is mined.

Copper concentrate exports from Indonesia’s Grasberg, the world’s second biggest copper mine, have plunged dramatically as operations shift from open pit to underground. Production is expected to fall from 1.2 million tonnes of copper concentrate last year to just 200,000t in 2019.

Major South American copper miners have also been forced to cut production.

A two-month strike in Peru at MMG’s Las Bambas mine meant a 15% drop in second-quarter output.

In Chile, Codelco’s Chuquicamata mine is expected to see a 40% fall in production over the next two years. A $5-billion expansion, moving from open-pit to underground, will take five years to reach full output of 300,000 tonnes per annum. Production will fall from an expected 459,000 tonnes in 2019 to 182,000t in 2021.

State-owned Codelco recently announced it will scale back an ambitious $40-billion plan to upgrade its mines over the next decade, after reporting a 57% drop in earnings due to heavy rains this past spring, a prolonged strike at Chuquicamata and lower metals prices. The world’s largest copper company also said it will reduce spending through 2028 by 20%, or $8 billion.

Shipments from BHP’s Escondida are expected to drop by 85% this year due to operations moving from open-pit to underground. The largest copper mine on the planet is expected to take until 2022 to re-gain full production.

These cuts are significant to the global copper market because Chile is the world’s biggest copper-producing nation – supplying 30% of the world’s red metal.

Regional instability

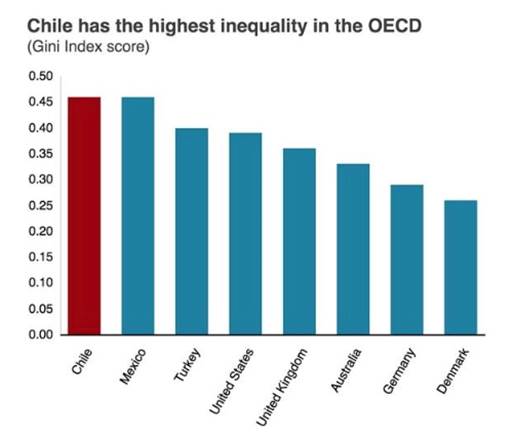

Recent country-wide protests over transit prices and perceived inequality have yet to seriously impact production, although protests have interrupted supply chains. Longshoremen have gone on strike several times since late October, in solidarity with other anti-inequality demonstrators.

Copper investors should also be aware of current and pending social unrest in other parts of South America, including Venezuela (an economic basket-case), Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru, the latter particularly in the southern region of Arequipa. Bloomberg reports on Peru’s President Martin Vicarra, engaged in a high-stakes experiment to harness public outrage over rampant corruption and blow up the establishment, while trying to keep Peru’s mining-dependent economy on track.

Adding to the turmoil, Vicarra this fall dismissed the Opposition-controlled Congress, so the country is without an assembly until elections on Jan. 26, 2020. He also has a mixed record on mining, having led negotiations for a larger share of royalties from Southern Copper, then two years later brokering talks to end community protests against Anglo American’s plans to build a major copper mine.

The upshot is, while Peru is the second-largest copper producer, that supply is far from guaranteed. The country is just as prone to resource nationalism as its more colorful neighbors, like Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro or Ecuador’s former president, Rafael Correa. Three excerpts from the Bloomberg article suggest this is the case:

“Peru is a country with a weak state, extreme inequality and weak institutions,” said Steven Levitsky, a professor of government at Harvard University who has written widely on Peruvian democracy. “So there’s always a risk of protests and a risk the government falls.”

Peru is notorious for social conflict; barely a week passes without some demonstration against a mining company, a government policy or incomplete public works. So frequent are conflicts that an ombudsman tracks them monthly.

“I don’t get the impression this government wholeheartedly believes in the private sector,” said Roque Benavides, chairman of Compañía de Minas Buenaventura SAA, which has stakes in the country’s biggest copper and gold mines.

Questionable expansions

On top of all the supply constraints, copper grades have declined about 25% in Chile over the last decade – highlighting the urgent need for grassroots exploration to arrest the trend.

Cochilco, the Chilean Copper Commission, recognized falling grades in a report, noting production from existing mines will decline 19%, but says the drop will be offset by new mines and expansions.

These include:

- The $4.8 billion expansion of Teck’s Quebrada Blanca mine.

- Increased production guidance from Anglo-American, from 630,000 to 660,000 tonnes a year due to expansions at Los Bronces and Collahuasi.

Critics say these expansions are unrealistic and unlikely to come to fruition anytime soon. Los Bronces and Collahuasi are already high-grading (processing higher-grade ore) from their mines and can’t do that anymore once that ore runs out because they are working highly-disseminated porphyry deposits (ie. no high-grade veins). The Quebrada Blanca expansion won’t be online until 2024, and that’s if Teck can find a partner to kick in at least $2.5 billion.

Infrastructure constraints

Chile also has serious water and power issues that are likely to crimp higher production.

We have reported on the fight over water between SQM and Albemarle, and the Chilean government’s efforts to restrict water rights, in the Salar de Atacama – the center of Chile’s lithium production. With most of Chile’s mining taking place in the north, copper mines are also affected by water restrictions.

Antofagasta and BHP are among the mining companies hit by a ban on new permits to extract water from the southern portion of the salar’s watershed, which supplies BHP’s Escondida, the world’s largest copper mine, and Antofagasta’s Zaldivar Mine.

It’s not the first time the Chilean government has moved against miners with respect to challenges over water. In 2016 its environmental regulator, SMA, shut down the Maricunga gold mine operated by Kinross Gold, over environmental concerns. Kinross was ordered to stop withdrawing water from local wells used to feed the operation. Shuttering the mine meant laying off 300 workers.

Drought watch

Going beyond mainstream news, it’s interesting to observe how higher frequency of droughts, linked to a warming climate, could affect future copper supply.

World Water Development Report warns over 5 billion people could see water shortages by 2050, leading to conflicts over water unless actions are taken to reduce stress on rivers, lakes, wetlands and reservoirs, states The Guardian.

Two-thirds of the world’s population lives in drought conditions for at least one month every year. One in four countries face the prospect of running out of water; 17 are considered to be under extremely high water stress, meaning they are using almost all the water they have, according to new data from the World Resources Institute. Thirty-three cities with a combined population of over 255 million are in the same predicament, “with repercussions for public health and social unrest,” New York Times reported. By 2040 that number is expected to rise to 45 cities encompassing nearly half a billion people.

Cities that have faced acute shortages recently include Sao Paulo, Brazil, Chennai, India and Cape Town, which narrowly escaped all its dams running dry in 2018. Mexico City draws so much groundwater that it is literally sinking.

The problem of water stress is closely connected to climate change. A report from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change notes developing countries like India are likely to be worst hit by climate change due to the frequency of droughts, which will lead to water shortages and problems with food production.

Droughts and mining

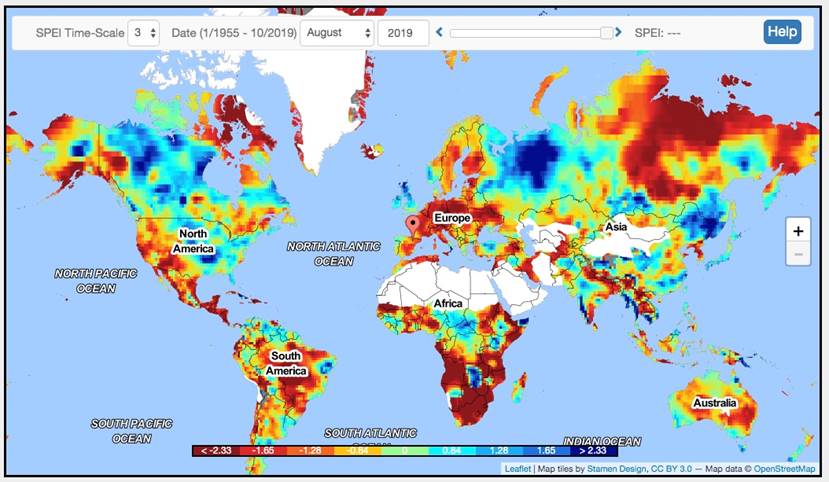

The latest data from the SPEI Global Drought Monitor is revealing for the amount of landmass that was experiencing severe water shortages as of August, 2019 – indicated by the red to crimson areas. It is alarming to notice that much of this area corresponds to the world’s major copper producers, including most of Southern Africa (eg. Zambia), Australia, Russia, the southern United States, Mexico and northern Chile/ Peru.

It’s impossible to mine most minerals without using copious amounts of water.

According to the US Geological Survey, a little over 100,000 gallons per ton of copper was used in the production of copper from domestic ores. (the USGS study is dated but there is no reason to presume significantly less water is used today). Nearly all of the 60 million gallons per day of use, occurred in arid states such as Arizona, Nevada and Utah.

This amount of water extraction would be acceptable if the rivers, lakes and aquifers the water came from were being regularly recharged, but this is not the case.

According to the EPA, four out of five state water managers expect water shortages in some part of their states over the next decade.

A major concern is over water levels in the Ogallala Aquifer under the US Great Plains. The Ogallala is the world’s largest known aquifer having an approximate area of 450,600 square kilometers and stretches from southern South Dakota through parts of Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico and northern Texas.

From the late 19th century until 2005 the US Geological Survey estimates irrigation pulled 253 million acre-feet from the aquifer – about 9% of its total volume. From 2011 to 2017 it reportedly shrank twice as fast as it had over the previous 60 years. In three leading grain-producing states – Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas – the underground water table has dropped by more than 30 meters.

Over-use is exacerbated by extended droughts caused by global warming. Precipitation is shifting from the mid-latitudes to the low and high latitudes – wet areas are becoming wetter and dry areas drier. Less rainfall in the mid-latitudes means less new water to refill the aquifers that are being depleted the fastest.

Streams, rivers and lakes are almost always closely connected with an aquifer. The depletion of aquifers doesn’t allow these surface waters to be recharged; lower water levels in aquifers are reflected in reduced amounts of water flowing at the surface.

The US uses so much water from their river systems that in some, nothing reaches the river’s destination. No water reaches the mouth of the Colorado River – low levels could force water shortages in Arizona, Nevada and Mexico by 2020.

The largest US man-made reservoir, Lake Mead, is only about 38% full. The Colorado River Basin which feeds Lake Mead and Lake Powell (48% full) has been drying out over the past two decades. Demands from farms and cities, compounded by growing populations, drought and climate change, are straining the Colorado River and its reservoirs, notes The Denver Post.

The problem of reservoir and aquifer depletion is global. According to the Stockholm International Water Institute, the 10 largest water users are India, China, the United States, Pakistan, Japan, Thailand, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Mexico and the Russian Federation.

As of 2016, of 37 important bodies of groundwater that are taxed for direct human consumption, 22, including most of the ones in Africa and a few in North America, had dried up completely.

The world’s biggest reservoir is currently in danger of losing so much water it could cease power production. Bloomberg reported the Kariba dam’s water level has fallen to 10% of usable storage – its lowest in more than two decades.

The lack of rainfall could force Zambia and Zimbabwe, who share the world’s largest man-made reservoir, to completely shut down power generation for the first time ever. The two countries depend on the Kariba dam for nearly half of their electricity generation capacity.

According to Bloomberg consumers in each country have already faced daily power cuts lasting up to 18 hours; the plant on the Zimbabwe side is only producing about 100 megawatts of its 1,050MW capacity.

Could the power crunch impact the copper mines of Zambia, the world’s seventh largest red metal miner? You bet. Bloomberg states: Households and factories have borne the brunt of the power shortage in Zambia, as the government has sought to minimize the impact on the copper mining companies that provide about 70% of the country’s export earnings.

It appears likely that, should the drought continue, Zambian mines would be forced to cut production just as some of the world’s largest copper miners in Chile have – further accentuating the copper supply shortfall.

Already we see some of the world’s largest mining companies facing serious financial risk due to water shortages. According to Earth & Space Science News, These risks range from the mandate to build expensive desalination plants to augment supplies to partial or total shutdown of mines.

Combining historical records of drought frequency and severity, with annual production from the mines of 15 companies, the “Palmer drought severity index” calculated the likelihood of a drought occurring at each location each year, and how the drought would affect annual production.

It found that Barrick, the second largest gold producer in the world, would encounter a 5% chance that around 35% of the value of its global mine production would be affected by a major drought event every 10 years. Or to put it in monetary terms, Barrick has a 5% chance of losing nearly $1 billion worth of production every year.

Barrick’s competitor Newmont (before it merged with Goldcorp to become the largest gold producer) runs a 5% chance of losing $0.6 billion a year because of drought.

Ideally, mining companies would cut production to save water, which would at the same time reduce the probability of conflicts with other water users dealing with a scarce water supply, such as farmers and downstream communities.

But this is not what we are seeing. In Bolivia, a state of emergency was declared in 2016 when the Andean nation suffered its worst drought in 25 years. Yet rather than decrease their water usage, mining companies increased production to take advantage of high metals prices. The resulting boom in mining projects required more water, thus worsening the shortage. Bolivia’s mining industry uses nearly 100,000 cubic meters of water a day, the equivalent amount of water consumed by the capital, La Paz, in two days. Bolivia’s aquifers fell below 50%.

More recently, Indian multinational Adani came under fire from environmental groups over its plan to take 12.5 billion liters of water from a river in drought-stricken Queensland, to feed its proposed Carmichael coal mine.

ABC News reports the environmentalists were enraged after the federal government decided the project did not need an environmental assessment, because the “water trigger” only applies to projects whereby the water is used to extract coal. With the Carmichael mine, Adani plans to use the water for washing coal and dust management.

Both of the above examples show the kinds of conflicts that can occur between mining companies and competing water users in times of scarcity.

EVs and 5G

As supply tightens, the demand for copper keeps going up and up. Copper products are needed in homes, vehicles, computers, TVs, microwaves, public transportation systems (trains, airplanes) and the latest copper consumable, electric vehicles.

In EVs, copper is a major component used in the electric motor, batteries, inverters, wiring and in charging stations. An EV has nearly 10 times as much copper in its battery as a regular gas-powered car or truck.

The IEA forecasts a more than quadrupling of EV sales in the next decade, from 5.1 million in 2018 to 23 million in 2030. That year the number of electrics not counting two and three-wheelers will exceed 130 million.

Earlier this year, research quoted in Barron’s said the mining industry will need to produce 5 million tonnes of copper a month by 2030, which is about 2.5 times the amount produced this year, just to meet demand from EVs.

Another interesting but largely un-reported fact is the amount of copper that is going to be needed in the shift to 5G networks.

Upgrading cellular networks from 4G to 5G is expected to result in a vast improvement in service, including nearly 100% network availability, 1,000 times the bandwidth and 10 gigabit-per-second (Gbps) speeds. With 5G, it’s possible to download a movie in less than 4 seconds compared to about 6 minutes on 4G.

However 5G isn’t only about mobile speeds, it’s also the foundation for the “Internet of Things” that connects a multitude of industrial computer networks, and virtual reality (VR) applications across a wide swath of industries.

The problem with implementing 5G is the need for a large number of small cells with low-power base stations, to provide the necessary coverage and capacity. Ie. while a typical 4G macro cell covers around 25 square kilometers, 5G could require 20 or more cells just to cover one sq km. More antennas are also expected to be needed to boost the signal. Microwave Journal explains:

The result of this is that, even though 5G is a wireless technology, its deployment will involve a lot more fiber and copper cable to connect equipment, both within the radio access network domain and back to the routing and core network infrastructure. Furthermore, 5G will require many more antennas than 4G ever did. That’s why this continuous demand for faster and more efficient connectivity across the world calls for state-of-the-art cable infrastructure to make 5G possible and to break down these barriers.

In Japan, demand for copper cables is seen growing 2.6% from 696,000 tonnes in 2018 to 714,000t in 2022, and copper for rolled copper alloy products growing 6% to 690,000t during the same period, according to the state-run Japan Oil, Gas and Metal National Corporation, or JOGMEC.

S&P Global Platts quotes the chairman of the Japan Mining Industry Association saying that the demand for electric vehicles and the rollout of 5G telecommunication infrastructure will support future demand for copper, zinc, lead and nickel.

Another report by Roskill forecasts total copper consumption will exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization and electricity demand. Electric vehicles and associated network infrastructure may contribute between 3.1 and 4Mt of net growth by 2035, according to Roskill.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis is more evidence of the coming copper shortage that, when plotted against strong demand for copper amid explosive growth for EVs, 5G networks and all the usual applications for copper, is likely to elevate copper prices substantially over the next few years.

Along with copper mine output interruptions this year owing to mines moving underground, strikes and weather, we have growing regional instability in South America threatening to further restrict production – particularly in Chile and Peru.

And then there’s the long-term structural problem with water. Many of the world’s copper mines are situated in the regions most vulnerable to droughts. We know that we are facing a 15-million-tonne supply deficit by 2035, unless new copper mines can be discovered and put into production to replace the ones lost to reserves depletion. But new mines put pressure on scarce water supplies. Can the mining industry manage to find enough copper, and enough water, to increase supply to meet demand, without sucking water supplies dry, leading residents that depend on the same water sources to a Day Zero reckoning?

It seems like a very big ask. What we do know is that copper, and water, in future will become scarcer, and more expensive.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.