Copper, lithium, graphite: Electrification demand strengthens as supplies tighten

2022.02.14

The move away from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles to EVs run on batteries is happening in almost every country. Governments are spending billions on EV charging infrastructure and subsidies to incentivize consumers to switch to hybrids and plug-in electric cars, vans and trucks. China is the leader but other countries are catching up, as large automakers like Volkswagen, Mercedes Benz, GM and Ford come out with new EV models and plan new EV manufacturing/ assembly plants in North America and Europe.

Electric vehicles were slow to catch on, but they are becoming more common, especially in urban environments. According to Auto Trader, 91% of electric car owners say they wouldn’t consider trading in for a gas or diesel version, and more consumers are seeing the value in sustainable transportation.

Not only do we need to figure out a way to transition from gas and diesel-powered vehicles, but there is also the question of how to fill the batteries demanded by electrification. Creating that energy — mostly solar and wind but also hydroelectric power — involves a massive use of metals to build batteries, battery storage systems, transmission lines and smart grids.

The three most critical inputs in the race to electrify and decarbonize the globe are copper, lithium and graphite.

The continued movement towards electric vehicles is a huge copper driver. EVs use about four times as much copper as regular internal combustion engine vehicles.

Copper, too, is needed for charging stations and renewable energy, particularly in photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines.

The electrification of the global transportation system doesn’t happen without lithium and graphite needed for lithium-ion batteries that go into electric vehicles.

Lithium prices have taken off in China, with soaring electric-vehicle sales underpinning a five-fold gain over the past year.

According to S&P Global, further demand growth in 2022 will mean a lithium deficit this year as use of the material outstrips production and depletes stockpiles.

Graphite is included on a list of 23 critical metals the US Geological Survey has deemed critical to the national economy and national security.

An average plug-in EV has 70 kg of graphite. Every 1 million EVs requires about 75,000 tonnes of natural graphite, equivalent to a 10% increase in flake graphite demand.

A White House report on critical supply chains showed that graphite demand for clean energy applications will require 25 times more graphite by 2040 than was produced in 2020.

It’s thought that battery demand could gobble up well over 1.6 million tonnes of flake graphite per year (out of a 2020 market, all uses, of 1.1Mt). Remember, the mining industry still needs to supply other graphite end-users. Currently, the automotive and steel industries are the largest consumers of graphite with demand across both rising at 5% per annum.

Explosive demand for EVs and charging stations

Of course the main reason for the supply deficits expected in all three of the main electrification metals — copper, lithium and graphite — is increasing EV popularity, and sales.

According to a joint report from Ernst & Young (EY) and Eurelectric, Europe will have 130 million EVs by 2025.

The report’s projections, cited by BNN Bloomberg, show Europe’s EV fleet growing from its current <5 million to 65 million by 2030, then doubling over the following five years. EY forecasts this number of EVS will require 65 million chargers (the majority being home-based) and an infrastructure investment of $134 billion.

The rapid adoption of EVs in Europe presents utility providers with a challenge: building a network of 9 million chargers along roadways, at workplaces and at fleet-charging hubs. Currently there are only about 445,000 such chargers.

According to EY’s calculations, EVs could increase peak loads on the electricity grid by 90% along highways, where drivers expect fast charging on demand. Managing these surges will require on-site solar and energy storage systems.

In urban areas, where commuters are charging their electric vehicles power in the evenings, EV expects a potential 86% increase in peak load.

At least 5 million tonnes more copper required

All of this will take copious amounts of copper.

An average EV contains about 85 kg of the red metal. Charging stations take 0.7 kg (for a 3.3 kW slow charger) or 8 kg (for a 200 kW fast charger), according to the Copper Alliance.

The Biden administration is planning on spending $5 billion over five years to install EV chargers, mostly along interstate highways, with another $2.5B given to rural and under-served communities. The funds are coming from the trillion-dollar infrastructure bill passed by Congress in November.

In a nod to his green energy supporters, Biden has set a goal of 500,000 public charging stations by 2030, a five-fold increase from the 100,000 in place already. Most of these chargers are “Level 2” chargers powered at 6 to 8 kW, so if we assume a copper content of roughly 1.5 kg per charger, an additional 400,000 chargers would need 600,000 kg of copper or 600 tonnes (1 tonne = 1,000 kg).

For Europe to meet its charging infrastructure goal of 9 million public chargers, the extra 8,550,000 chargers, if they are Level 2s, would require 12,825,000 kg of copper, or 12,825 tonnes.

If these figures are correct, supplying enough copper for US and European charging stations is do-able.

However if Europe’s EV fleet grows to 65 million as predicted, by 2030, the amount of copper required for the additional 60 million electric cars @ 85 kg per EV, is 4,920,000,000 kg, or 4,920,000 tonnes. This is more than four times US copper production in 2021 of 1,200,000 tonnes, or 87% of Chile’s annual production, the world’s top copper-mining country.

Deloitte is predicting the United States will account for 14% of global EV sales in 2030, or 4.34 million units. At 85 kg of copper per EV, this amounts to 368,900,000 kg, or 369,000 tonnes.

To meet this demand, and remember we are only talking about copper demand for electric vehicles sold in the US and Europe, — we aren’t counting higher EV sales in other countries, along with millions more public and private charging stations to service them, all needing copper, plus supplying all the other copper markets, for construction, power transmission, telecommunications, etc. — would require 4,920,000 + 369,000 tonnes = 5,289,000 tonnes. This is equivalent to more than five Escondida mines (the largest in the world), with each producing 1 million tonnes per year. Just to provide enough copper for EVs in the United States and Europe.

Mining and metals consultancy CRU Group estimates that, without new capital investments, global copper mined production will drop below 12Mt by 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15 million tonnes.

According to CRU, there are over 200 copper mines that are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

Dire need for battery raw materials

Copper usage aside, the high uptake of electric vehicles is having a major impact on lithium-ion battery demand.

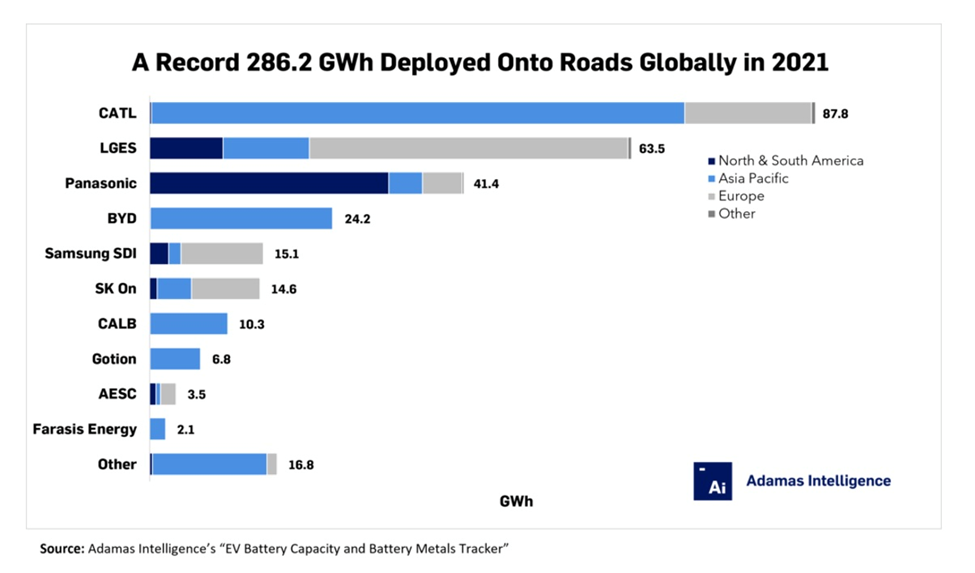

Globally, EV battery capacity hit a record in 2021, raising concerns over whether there will be enough raw materials to meet the need.

According to Adamas Intelligence, via Kitco, a record 286.2 gigawatt hours (GWh) of passenger EV battery capacity was deployed last year, more than double (+113%) the figure in 2020, as sales of battery-electric and plug-in hybrid vehicle sales surged.

With the sector consuming a growing amount of battery metals, especially lithium, graphite and cobalt, the International Energy Agency predicts at least 30 times more lithium, nickel, cobalt and other minerals could be required by 2040 to meet global climate change targets.

The markets for lithium and graphite illustrate the pressing need.

Globally, lithium production hit a record-high in 2021 of 100,000 tonnes, which is a 21% increase from 2020. According to the US Geological Survey, output has increased in response to strong demand from the lithium battery market and increased prices.

If spot lithium prices in China stay high, they could add up to $1,000 to the cost of a new EV, states Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (BMI), a London-based battery metals information provider. Citigroup on Wednesday almost doubled its lithium price forecast for 2022.

While supply is currently outstripping demand, the gap is closing. According to the USGS, global lithium consumption in 2021 was estimated at 93,000 tonnes, a 33% increase from 2020, leaving a relatively small surplus of 7,000 tonnes.

“Lithium supply security has become a top priority for technology companies in Asia, Europe, and the United States,” the USGS said in its latest report.

The S&P Global Platts China Battery Metals Outlook for 2022 says China’s lithium market is set to face tightening supplies throughout 2022 as the demand-supply mismatch widens.

According to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, EV sales in the country will reach 5 million units this year, up 40% from 2021.

S&P says further demand growth in 2022 will mean a lithium deficit this year as use of the material outstrips production and depletes stockpiles.

Another reliable source, BMI, forecasts supply will fall short of demand, even as it predicts output to roughly double from 2021 to 2025.

“There’s a complete overoptimism about the responsiveness of supply in the lithium market,” Bloomberg quoted Andrew Miller, BMI’s chief operating officer. “It’s very hard to see how it’s going to accelerate at the speed that the battery market and electric vehicles are accelerating.”

Bloomberg notes the relatively small size of the lithium market, compared to say, copper or iron ore, is preventing the major mining companies from getting into the lithium game, for fear of overwhelming supply and crushing prices, like what happened a few years ago. Rio Tinto is the only large-cap miner so far that has been tempted to move into the metal.

The article also says that supply could lag due to the industry’s reputation for missing targets, quoting an estimation by McKinsey & Co that more than 80% of projects come in late and over budget.

Environmental hurdles are another brake on supply. The most recent example is Rio Tinto’s controversial lithium project in Serbia, now on hold due to environmental protests.

Battery demand could gobble up well over 1.6 million tonnes of flake graphite per year (out of a 2020 market, all uses, of 1.1Mt) — only flake graphite, upgraded to 99.9% purity, and synthetic graphite (made from petroleum coke, a very expensive process) can be used in lithium-ion batteries.

Global graphite consumption has been increasing steadily almost every year since 2013.

According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, the flake graphite feedstock required to supply the world’s lithium-ion anode market is projected to reach 1.25 million tonnes per annum by 2025. At this rate, demand will easily outstrip supply in a few years.

Analyst Visual Capitalist Elements, via Battery & Energy Storage Technology, says demand for graphite from battery makers is expected to expand 10.5-fold to 2030. They forecast the natural graphite market could be in deficit as early as 2023, due to a shortage of new sources outside China.

China is not only the world’s biggest graphite miner, it is also the number 1 refiner, handling a combined two-thirds of global cathode and anode production. Yet even China is feeling the pressure of steady, rising demand — the country in 2019 was a net graphite importer for the first time in its history.

According to Urbix, an American manufacturer of battery anode materials, due to the unprecedented global demand for lithium-ion batteries, a shortage of battery-grade graphite is expected as soon as this year. (graphite is predicted to remain the predominant anode material regardless of a battery’s cathode chemistry)

Conclusion: we don’t have the metals

According to Rio Tinto, among the metals most impacted by technology, including autonomous and electric vehicles, advanced robotics, renewable energy, advanced computing and IT, are tin, lithium, cobalt, silver, nickel and gold.

Other important new-economy metals include copper, used in EV motors and wiring, charging stations and renewable energy; graphite needed for the lithium-ion anode, and zinc for galvanized steel and advanced EV battery applications.

The supply chain for batteries, wind turbines, solar panels, electric motors, transmission lines, 5G — everything that is needed for a green economy — starts with metals and mining.

A green infrastructure and transportation spending push will mean a lot more metals will need to be mined, including lithium, nickel, and graphite for EV batteries; copper for electric vehicle wiring and renewable energy projects; silver for solar panels; rare earths for permanent magnets that go into EV motors and wind turbines; and silver/ tin for the hundreds of millions of solder points necessary in making the new electrified economy a reality.

In fact, battery/ energy metals demand is moving at such a break-neck speed, that supply will be extremely challenged to keep up. Without a major push by producers and junior miners to find and develop new mineral deposits, glaring supply deficits are going to beset the industry for some time.

These supply deficits are only going to increase our dependence on foreign suppliers, unless the West, meaning Europe and North America, make a major departure from the way we’ve been doing things and start mining and refining minerals.

Instead we go cap and hand to China, for the new electrification/ decarbonization metals.

Consider: China rules the electric vehicle supply chain. It is also a major player in renewable energy markets (solar & wind), and is building the most new nuclear power plants of any country.

In the rush to electrify/ decarbonize, is the West not just substituting one energy tyrant, Saudi Arabia and OPEC, for another? The world’s largest consumer of commodities already has a monopoly on rare earths mining/ processing, produces the most lithium and cobalt, and dominates the graphite market.

China controls about 85% of global cobalt supply, including an offtake agreement with Glencore, the largest producer of the mineral. Beijing also appears to be locking up nickel supply, through investments in the leading producer, Indonesia.

The United States is 100% import-reliant on 13 of the 35 critical minerals the Department of the Interior has classified. They include manganese, graphite and rare earths.

But the problem isn’t only critical metals.

One commodity whose bullish fundamentals stand out head and shoulders above the others, is copper, the metal we’re betting our electrified and decarbonized future on.

With all that is happening on the demand side for copper, combined with the supply pressures outlined, there is no getting around the fact that the copper market is not just undersupplied now, but will be vastly undersupplied in 10 years.

In a previous article we showed that four out of the five major copper projects in the pipeline right now either have offtake agreements in place with non-Western countries (South Korea and China), or the mines are partially owned by Japanese companies that have a say in where some of the mined copper is destined. (i.e. Japan)

We’re becoming short of copper in the West and there’s no two ways about it. We weren’t watching, we weren’t paying attention, we were asleep when China cornered the rare earths market back in 2010, and we were also blind to the Chinese locking up global supplies & processing capabilities for nickel, cobalt, graphite and lithium.

Then you look at what’s happening in four of the world’s largest copper-producing countries, Chile, Peru, Zambia and the DRC, all of which are rising threats for resource nationalism, making the required ramp-up in copper production to meet expected demand from electrification/ decarbonization all that much harder, if not impossible.

The Biden administration, despite talking up critical minerals independence, would prefer to gets its clean energy and EV raw materials from its allies, than support the messy, and politically unpalatable business of natural resource extraction.

Anti-mining decisions made under Biden’s watch include canceling a Trump-era move to renew mineral rights leases for the proposed Twin Metals copper-nickel mine in Minnesota; relaunching a process that could permanently protect Bristol Bay from the giant Pebble copper-gold mine proposed for Alaska; and slamming the brakes on a land swap agreement, initiated under Trump, that would have allowed the Resolution copper mine in Arizona to move forward.

We’re no better in Canada. Bill C-69, passed in 2019, broadens the scope of the environmental assessment process and adds more consultation with the public and particularly indigenous groups. According to the Business Council of BC, the law will lead to “greater difficulty securing permits… heightened uncertainty among company managers, project developers and investors.” and help “accelerate outflows of business investment to other jurisdictions”. Read more about C-69 and other Canadian obstacles to mining

Over-regulation, duplication by different levels of government, and a pandering to vocal-minority focus groups, have all combined to make mine approvals in Canada and the US some of the most costly and time-consuming in the Western world. It can take up to 20 years for a mine in North America to be developed, from discovery to commercial production.

Yet there is still time to turn this ship around.

Rush to Renewables and EVs Makes China the World’s New Energy master

Rick Mills audio interview by Cris Sheridan of Financial Sense University

The possibility of creating North America’s very own mine to battery to EV supply chain is within our grasp if we, as investors, cultivate the right companies and the right projects. The goal is certainly worthwhile: eliminating US/ Canadian dependence on foreign suppliers and driving down the cost of electric vehicles to the point where they are actually affordable to the average person and the transformation from fossil-fueled to electric vehicles is carried out successfully.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.