Copper and nickel market updates

2022.03.11

Copper

The global copper supply crisis is getting deeper with each passing day.

Even disregarding the military crisis in Europe and the piling sanctions against Russia that have rocked the commodity markets, copper has always been in a tough spot simply because of its fast-rising demand and the critical role in the modern economy.

More than 20 million tonnes of the metal are being consumed each year across a variety of industries; these include building construction, power generation and transmission, and electronic product manufacturing.

Roskill forecasts total copper consumption will more than double and exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization and electricity demand.

In recent years, the global transition towards clean energy has stretched the need for metals even further. More copper will be required to feed our renewable energy infrastructure, such as photovoltaic cells used for solar power and wind turbines.

The metal is also a key component in transportation vehicles, and with increasing emphasis on “electrification”, its demand will likely explode as the modern EV uses about four times as much copper as regular internal combustion engine vehicles.

In fact, analysts at Goldman Sachs are already calling copper “the new oil”, as the metal is a key part of sustainable technologies, including electric vehicle batteries and deriving clean energy.

Growing Copper Crisis

Success of the clean energy transition, though, depends on whether we can supply enough copper to meet future demands.

Copper consumption by green energy sectors alone is expected to jump five-fold in the 10 years to 2030, data from mining and metals consultancy CRU Group shows.

S&P Global Market Intelligence predicts that due to a shortage of projects, copper supply will lag demand starting as early as 2025, with global mine production dropping from last year’s 21.5Mt to roughly 15.9Mt in 2030.

Diminishing supply from currently operating mines, combined with the projected increase in demand for copper concentrate over 2021-2030, would result in a 3.85Mt production shortfall in 2025, S&P Global estimates.

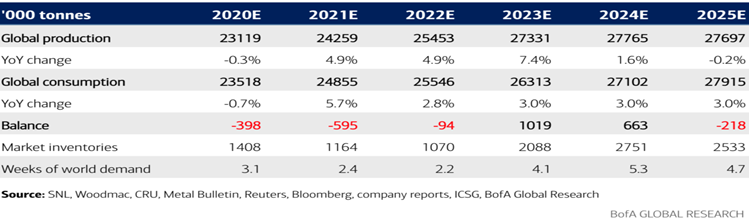

A similar timeline was given by Bank of America in a recent report, which predicts the copper market to flip into a deficit as early as 2025 following the completion of the current wave of project buildouts.

“While visibility over the near-term project pipeline is good, activity increases come with a wrinkle,” the bank’s analysts say. “Indeed, many of the projects currently developed have been in the making for almost three decades, and with exploration activity relatively limited in recent years, supply increases may fade from 2025.”

BloombergNEF estimates that in 20 years, the world’s copper miners must double the amount of global production — from the current 20 million tonnes annually to 40 million tonnes — just to match the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles.

This is a tough ask considering some of the world’s largest mines are seeing depleted copper reserves and lower ore grades, so it would be difficult for global production to even maintain a 20-million-tonne-per-year pace.

CRU estimates that without new capital investments, global copper mined production will drop below 12 million tonnes in 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15 million tonnes. According to CRU, there are over

200 copper mines that are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

Evidence of a growing copper crisis can be found in Chile, the world’s biggest producer of the metal.

Recent data from Chile’s statistics bureau shows that the nation’s copper output tumbled 15% in January from December, and 7.5% from January 2021, after weak performances from some of its biggest mines. Escondida, the world’s largest deposit, saw its production fall 4.4% year-on-year, while the Collahuasi mine recorded a 10% drop.

At just under 430,000 tonnes, Chile’s January copper output represents its lowest monthly output since 2011, a sign of what’s to come in the copper market and a harbinger of declining mine production. Chile is already coming into this year having experienced a 2% drop in its 2021 copper output.

While no clear reason was given for Chile’s production drop, it’s safe to assume that copper mines are indeed running out of ore. Given Chile accounts for 30% of the world’s supply, the negative impact would be felt the hardest there.

As AOTH have written before, reserves at copper mines are dwindling worldwide, and so are the grades. Copper grades have declined about 25% in Chile over the last decade, bringing less ore to market.

Making matters worse, after more than a decade of drought, freshwater supplies are becoming a big problem in Chile. Copper mines there happen to require lots of water to process sulfide ores, and the lower the grade, the more water must be used.

Since major copper miners are increasingly turning to low-grade sulfide deposits to beef up their production, their water consumption is expected to jump up to 20.9 cubic meters per second (about half an average household pool). Water scarcity in effect hinders their ability to produce.

Another event that has yet to come into play is Chile’s proposed nationalization of its copper industry. While the constitution still has several hurdles to overcome, the idea itself has already started to cause jitters and make miners nervous about their Chilean operations. Similar fears exist in neighboring Peru, the second-largest copper producer.

Nickel

The war in Ukraine has lit a fire under commodities and none is hotter than nickel. As Russian forces continued to pummel Ukrainian cities, Tuesday, nickel trading was suspended in London after prices more than doubled.

Activity on the London Metal Exchange (LME) was so frenzied, the 145-year-old bourse had to cancel trading after an unprecedented price spike saw brokers struggling to pay margin calls against unprofitable short positions.

The base metal used in stainless steel and electric-vehicle batteries surged more than 250% in two days, briefly hitting $100,000 a ton, as investors and industrial users who had sold nickel scrambled to buy the contracts back after prices rallied.

The largest-ever price move on the LME began shortly after the US considered banning Russian crude oil imports. This sparked a massive squeeze in commodity markets, including oil, gas, nickel, aluminum and palladium. All hit multi-year highs or new record highs, according to Bloomberg.

Nickel’s vertical price spike is seen in Kitco’s graph below. Note: while nickel has risen by about $11,000 a ton over the last five years, this week alone, it has jumped as much as $72,000.

The key driver behind the “short squeeze” was market participants with short positions, who were forced to close them out because they couldn’t meet margin calls.

Traders, miners and processors will often short metals as a hedge for their physical stocks, thinking that any volatility in the exchange position and physical stocks should cancel each other out. The risk is when prices rise sharply, anyone holding a short position will need greater collateral to pay margin calls.

On Monday, following a near doubling of the nickel price, the LME announced rule changes allowing traders to defer their contract obligations. The unusual move evoked memories of the 1985 “tin crisis”, when the exchange suspended tin trading for four years, pushing many brokers out of business.

Chinese entrepreneur Xiang Guangda was among the most hurt by the nickel short squeeze. Xiang, nicknamed “Big Shot”, is the chairman of Tsingshan Holding Group, the world’s largest nickel and stainless steel producer. Bloomberg said Xiang held a large short position on the LME through Tsingshan, which has been under growing pressure from its brokers to meet margin calls.

One of these brokers, a unit of China Construction Bank, was given more time by the LME to pay the hundreds of millions of dollars worth of margin calls it missed Monday. The payments were made Tuesday.

The LME said Tuesday’s cancelation of the nickel contract at $80,000 per tonne, and the deferred delivery of all physically settled contracts, followed a close monitoring of the ongoing impacts of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The bourse is also taking into account the recent “low-stock environment and high pricing volatility environment observed in various LME base metals, and in particular nickel.”

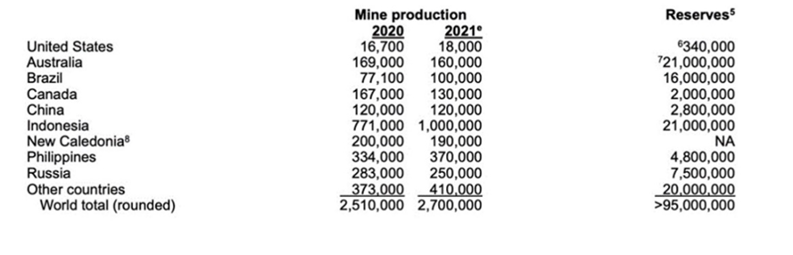

Russia is the third largest nickel producer in the world, in 2021 mining 250,000 tonnes, including 193,006 from Nornickel, the globe’s top producer of refined nickel. Nornickel’s output amounts to around 7% of global mine production, which in 2021 was 2.7 million tonnes, according to the US Geological Survey.

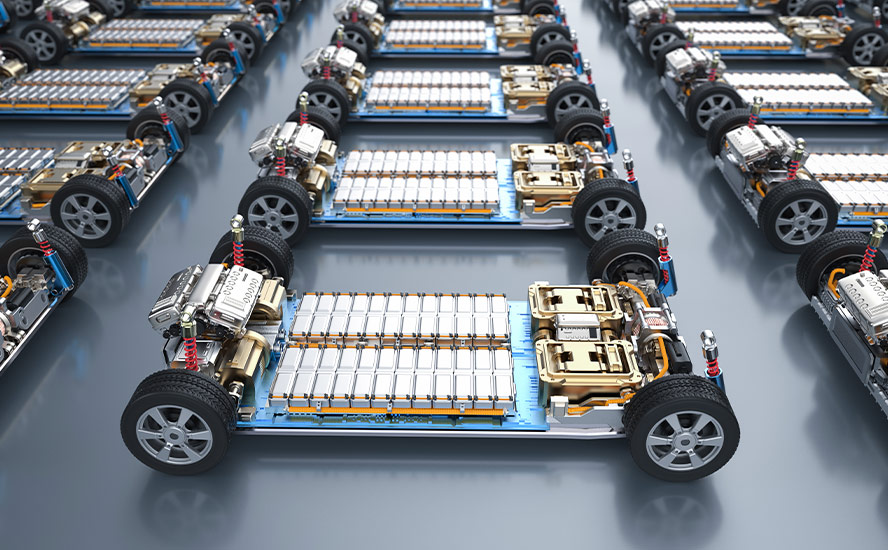

Note that Nornickel mines sulfide nickel, the kind best suited to lithium-ion batteries. (Sulfide nickel deposits are relatively rare, they comprise only 40% of nickel deposits found worldwide. The other 60% are nickel laterites. We can therefore say that Russia’s Nornickel mines 7% of the 40% of nickel sulfide deposits). This nickel can be processed at relatively low cost, and with minimal waste, using simple flotation, compared to the more expensive, and highly polluting techniques used to refine nickel from nickel laterites found in the world’s top nickel producer — Indonesia — the Philippines and New Caledonia.

Nickel prices were already pushing higher before the crisis began in late February — the market’s tight fundamentals reflected in low warehouse inventories and strong demand for nickel to be processed into EV battery cathode material.

A disruption to nickel supplies would not only harm nickel end users, but the entire lithium-ion battery supply chain because Nornickel mines sulfide nickel.

A report by UBS indicates that a deficit in nickel will come into play as soon as this year. By the end of the decade, UBS forecasts a large deficit of 2.2 million tonnes for the battery metal.

A more conservative estimate from Rystad Energy shows that demand for high-grade nickel used in EV batteries will outstrip supply by 2024. By then, global demand will climb to 3.4Mt, compared to 2.5Mt this year, while supply will grow to 3.2Mt.

The gap will then widen quickly to a deficit of 0.56Mt by 2026, driven by surging demand from the battery sector.

While batteries are not the dominant usage for nickel, that being stainless steel, electric vehicles’ share of nickel demand has been growing at a faster rate and is expected to trend up.

Wood Mackenzie estimates that of the 2.8 million tonnes demanded last year, 69% was used to make stainless steel and 11% to make batteries, up from 71% and 7% respectively in 2020. Batteries’ share of demand is expected to rise to 13% in 2022.

According to Rystad’s latest report, nickel demand from the stainless steel industry should grow at about 5% per year, while the market for batteries is poised to explode. “In an unconstrained supply scenario, batteries could require more than 1Mt of nickel metal by 2030, quadrupling from the current demand of 0.25Mt,” the energy research firm said.

Conclusion

With the world’s copper supply drying up, there would have to be more investments into new discoveries and turning them into producers of tomorrow.

According to reports, the mining industry must double the current production of 20Mt by 2040 to have a chance of coming close to meeting demand. This equates to one new Escondida mine (1Mt annual production) every year for the next 20 years.

We’re already seeing reserves dwindle at the biggest mines, with lower ore grades each year. Chile’s production has declined sharply is indicative of the pending supply crunch, which is once again driving copper prices toward record highs.

While getting 1Mtpa of additional output is difficult to achieve, finding the right investments in projects leading to copper discoveries would help to close the supply gap. According to CRU, the copper industry needs to spend upwards of $100 billion to erase what it estimates to be a 4.7Mt deficit by 2030.

Nickel was already doing well before the war but we now have an extremely tight market particularly for sulfide nickel, the kind of nickel best suited to battery-making. Western sanctions have put sulfide nickel from Russia’s largest nickel producer, Nornickel, in jeopardy. And while some may sniff at the fact that Russia is only the third-largest nickel producer, behind Indonesia and the Philippines, Nornickel mines 7% of the world’s sulfide nickel, of which less than half (40%) is in sulfide nickel deposits. The potential certainly is there for a shortage of sulfide nickel to filter down the supply chain to electric vehicles.

Goldman Sachs has forecast the nickel market to be in a 30,000-tonne deficit in 2022, more than double the 13,000-tonne deficit it predicted last August.

Tesla’s Elon Musk identified the shortage of nickel as one of the biggest hurdles to increasing production of EV batteries, in 2020 promising large contracts to mining companies able to supply the EV maker with sustainable nickel.

At the time, Musk wanted nickel because it was cheaper than cobalt; if elevated prices continue, nickel threatens to ratchet up costs for electric-vehicle batteries and complicate the gasoline to electric-vehicle transition.

However we must also keep in mind, that even though battery chemistries could change, the metals essential to lithum-ion technology will still be required. It’s also interesting to see the reversal of globalization, a phenomenon that started with former President Trump.

The United States has put zinc and nickel on their updated critical minerals list (also lithium, cobalt, graphite, palladium and platinum), and policymakers are finally starting to realize that relying on China and Russia for the raw materials needed for the new green economy isn’t such a wise idea.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.