Commodities are the place to be. Here’s why

2022.02.12

Commodities are considered one of the best places to park investment capital during inflationary periods.

The reason is simple. As demand for goods and services rise, so do their prices, along with the raw materials (commodities) needed to produce the finished products. Investing in commodities is therefore considered a hedge against inflation.

The latest inflation statistics show the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) up 7%, year over year, in December — a 40-year high. In Canada, the prices of goods and services have quadrupled over the past 12 months, from 1% to 4.8%, the most in 30 years.

An investor who bet on the top commodities ETF, in the depths of the covid-19 public health/ economic crisis, would have done quite well.

The Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index (BCOMSP), which tracks 23 energy, metals and crop futures, is considered a good barometer of the sector. In March 2020, the index plummeted to a four-year low, just missing a nine-year bottom reached in December 2015. In less than two years BCOMSP has more than doubled, to the current 554.61, as of this writing. The chart below says more than words can.

In 2021, commodities outperformed all other asset classes, and they are expected to be competitive in 2022.

A commodities “super-cycle” can happen in the late stages of an economic expansion, when growth is so strong, companies can’t produce enough commodities to keep up with demand. The last super-cycle was 2004-08. From the bottom in 2003 to the peak in 2008, commodities rose over 300%.

The commodities super-cycle of the 2000s collapsed in the Great Recession of 2008, then resumed from 2009 to 2011. It ended in the bear market of 2011-15.

Many are pointing to the formation of a new super-cycle, driven not by fossil fuels and the rise of China, but by “green” metals needed for technologies that mitigate the negative effects of climate change.

On top of surging demand for metals needed to feed so-called “green infrastructure” programs being pursued by the United States, Europe and China, we have current and emerging structural deficits for several metals, that will keep prices buoyant for the foreseeable future.

Over the past year, for example, tight supply is reflected in the rising prices of copper, nickel, zinc, lead and aluminum.

Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research for Goldman Sachs, in January reiterated his (and the bank’s) view that we are at the beginning of a decade-long commodity supercycle. Currie told CNBC’s ‘Squawk Box” that the fundamental setup in the commodities complex, including oil and metals, “remains incredibly bullish.”

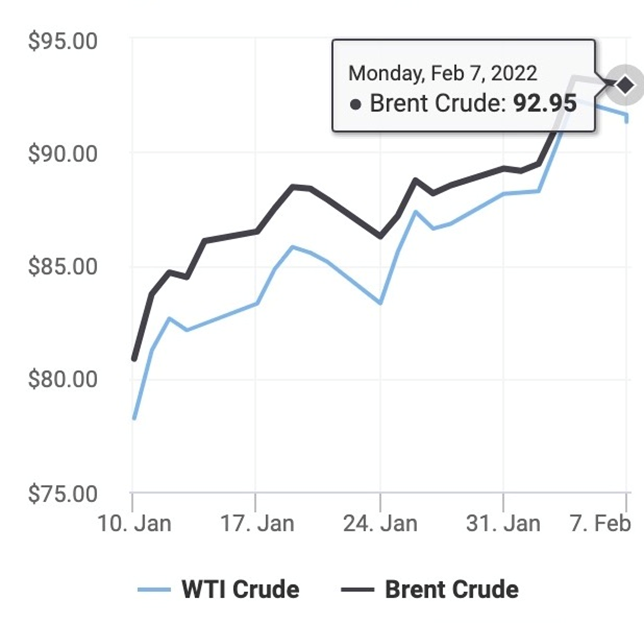

Currie gives three reasons for this. First is the fact that global oil inventories are about 5% below their five-year moving average. Last month Goldman Sachs hiked its Brent crude price forecast to $90/barrel from an earlier $80. Both the Brent and WTI crude oil benchmarks have exceeded $90, at time of writing.

Second, investing in the oil & gas industry has gone out of favor, with ESG headwinds posing a significant challenge for a sector that badly needs new investments, for production to keep up with demand.

Saudi Arabia has warned that, without re-investing in the oil industry to find more deposits, the world could be short 30 million barrels a day in just eight years.

In the current under-supplied environment, high oil and natural gas prices will be with us for the foreseeable future. Read more

A third reason for Currie’s bullish stance is related to the second — “a complete redirection of capital” over the past few years from investing in old-world economy commodities such as oil and coal, to renewables and ESG, which stands for economic, social and governance. Under-investment in new mines and new oil discoveries has resulted in a demand imbalance.

A fourth and fifth reason that commodities are doing so well right now, is due to the pandemic. By first halting and then restarting supply chains, supply and demand fundamentals for raw materials were thrown out of whack. Moreover, a shift in the spending habits of consumers, from services like air travel and dining out, to durable goods such as exercise machines and home renovations, have increased demand for metals and wood products.

(Last spring the price of lumber hit a record high of nearly $1,200 per thousand board feet, 250% more expensive than a year earlier. Though it fell as low as US$410 last August, lumber has climbed back up to around $1,115. Ongoing strong demand from 2021, including an uptick in US housing starts, combined with supply constraints from northwestern BC, are keeping prices high, according to Canadian Forest Industries).

Significantly for us at AOTH, Currie is especially bullish on metals, which he compares to oil in the 2000s due to so-called “green capex”. Bloomberg has Currie declaring copper as “the new oil”, noting it’s absolutely indispensable in global decarbonization strategies with copper shortages already being felt.

Other notable clean energy experts share Currie’s views.

New energy research outfit Bloomberg New Energy Finance says the energy transition is responsible for driving the next commodity super-cycle, with immense prospects for technology manufacturers, energy traders, and investors. Indeed, BNEF estimates that the global transition will require ~$173 trillion in energy supply and infrastructure investment over the next three decades, with renewable energy expected to provide 85% of our energy needs by 2050.

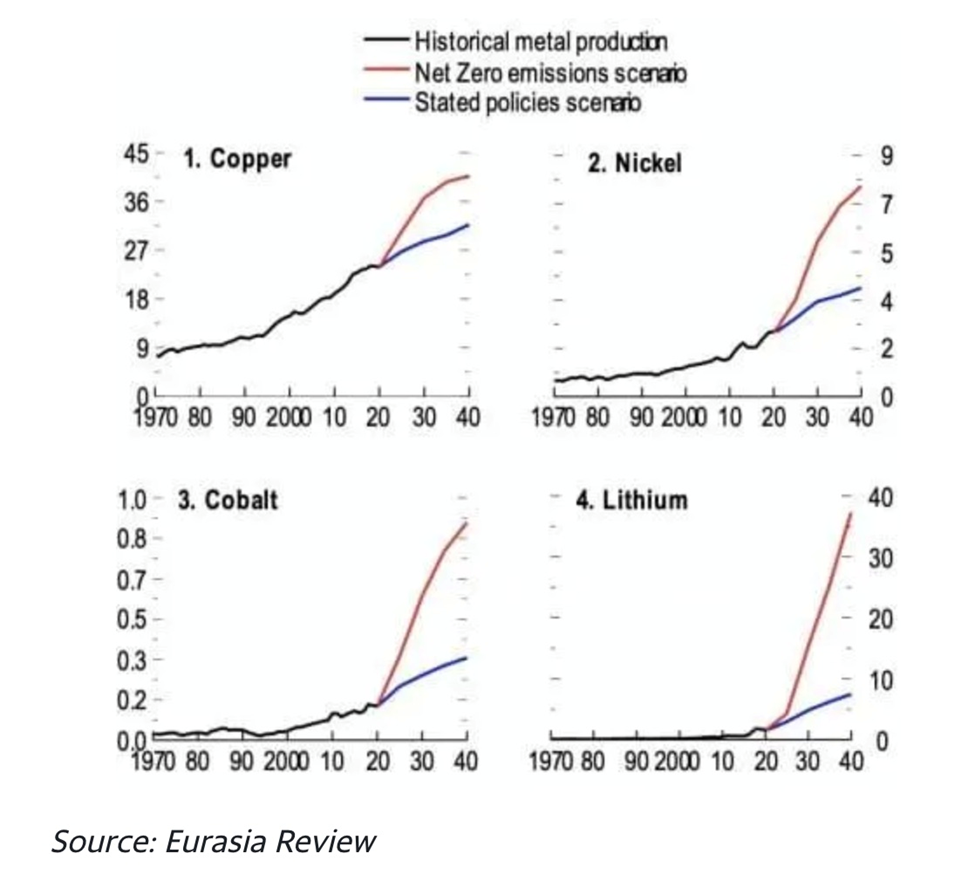

Clean energy technologies require more metals than their fossil fuel-based counterparts. According to a recent Eurasia Review analysis, prices for copper, nickel, cobalt, and lithium could reach historical peaks for an unprecedented, sustained period in a net-zero emissions scenario, with the total value of production rising more than four-fold for the period 2021-2040, and even rivaling the total value of crude oil production.

Referring again to the Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index, which reached a new record earlier this year, driven in part by surging oil prices, Currie said this week he’s never seen commodity markets pricing in the shortages they are right now.

“I’ve been doing this 30 years and I’ve never seen markets like this,” the commodity expert said in a Bloomberg TV interview. “This is a molecule crisis. We’re out of everything, I don’t care if it’s oil, gas, coal, copper, aluminum, you name it we’re out of it.”

As evidence, Currie points to the futures curves in several markets that are trading in “super-backwardation”.

Backwardation is when a commodity’s spot price is higher than its prices trading in the futures market.

The primary cause of backwardation in the commodities’ futures markets is a shortage of the commodity in the spot market.

Super-backwardation indicates that traders are paying large premiums for immediate supply. Diesel futures, for example, are in their strongest backwardation since 2008.

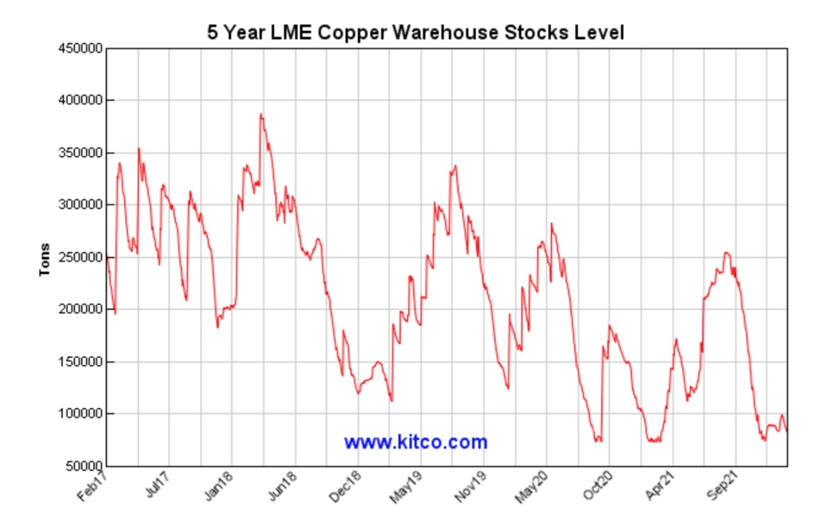

As Bloomberg points out, All six of the main industrial metals traded on the London Metal Exchange moved into backwardation late last year, in a rare synchronized bout of tightness last seen in 2007.

Demand themes

There are demand-driven reasons for keeping metal prices higher, and structural issues surrounding the supply of certain mined commodities. First, the demand side.

In 2003 the commodities super-cycle was driven by growth in China, which demanded almost every commodity under the sun to meet double-digit annual increases to its GDP. This time is different. I believe we are going to see demand across the board for nearly every type of commodity, based on infrastructure renewal, electrification, reduction of carbon, and food demand.

When I was interviewed by Financial Sense, I explained the four over-riding global themes I believe are setting us up for a bull market in commodities like no other in history. They are:

- Blacktop/ basic infrastructure such as roads, bridges, water & sewer systems, etc., that has been poorly maintained. Governments need to spend trillions to repair their crumbling infrastructure and bring it up to the needs of a modern economy. The latter includes investments in smart power grids, 5G and high-speed rail.

- Electrification of the global transportation system. The move away from fossil-fuel-powered vehicles to EVs run on batteries is happening in almost every country. Governments are spending billions on EV charging infrastructure and subsidies to incentivize consumers to switch to hybrids and plug-in electric cars, vans and trucks. China is the leader but other countries are catching up, as large automakers like Volkswagen, Mercedes Benz, GM and Ford come out with new EV models and plan new EV manufacturing/ assembly plants in North America and Europe.

- Reducing our carbon footprint. Not only do we need to figure out a way to transition from gas and diesel-powered vehicles, but there is also the question of how to fill the batteries demanded by electrification. Creating that energy — mostly solar and wind but also hydro-electric power — involves a massive use of metals to build batteries, battery storage systems, transmission lines and smart grids.

- Meeting the global demand for food. Food supplies are constantly under pressure due to expanding populations, and as developing countries move up the “food chain” to include more protein in their diets. Reducing food insecurity thus has to be an important part of this latest commodities boom, which sees the first three trends happening all at the same time.

The new “green economy” rejects dirty sources of energy and transportation, namely coal, oil, and natural gas. Instead, it relies on carbon-friendly modes of transport and energy production, including electric vehicles, renewable power, and energy storage, as well as mobile technology (5G) and rapid adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies needing increased computing power.

Transportation makes up 29% of global emissions, so transitioning from gas-powered cars and trucks to plug-in vehicles, as well as high-speed rail, is an important part of the plan to wean ourselves off fossil fuels.

Supply constraints

However, to accomplish all of the above, will require a colossal boost in the production of mined materials.

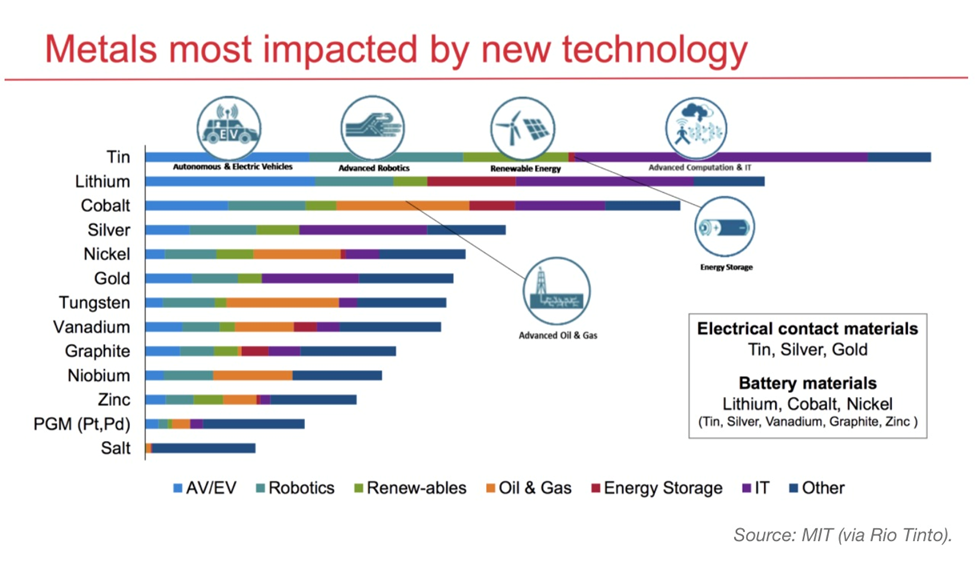

According to Rio Tinto, among the metals most impacted by technology, including autonomous and electric vehicles, advanced robotics, renewable energy, advanced computing and IT, are tin, followed by followed by lithium, cobalt, silver, nickel and gold.

Other important new-economy metals include copper, used in EV motors and wiring, charging stations and renewable energy; graphite needed for the lithium-ion anode, and zinc for galvanized steel and advanced EV battery applications.

Lead time is particularly relevant to mining; it can take up to 20 years for a new mine to come online, from discovery and resource delineation, to development, permitting, construction and finally, commercial production.

After the last commodities boom came to an abrupt halt in the mid-2010s, several mining companies savaged by plummeting metals prices were forced to take billion-dollar write-downs and enact fiscal discipline amid shareholder pressure.

The result was slashed spending on exploration, presaging a supply shortfall for a number of metals, especially copper. As BNN Bloomberg concisely puts it, The result is that while demand is surging, supply isn’t.

Indeed most of the low-hanging fruit has been picked, meaning that exploration companies and major/ mid-tier mining outfits need to go further afield to find new mineral deposits. This metal is often lower grade and more difficult to extract, requiring complex, and expensive, mining methods and metallurgical processing.

Below is a summary of the supply issues facing some of the most important metals needed for the green economy, as countries, companies and individuals move further down the road to decarbonization and electrification.

Running on empty

Copper

A report by Goehring & Rozencwajg, which specializes in natural resource investments, points out that the primary concern for copper supply lies in the inevitable depletion of existing copper mines — a problem that has been brewing for over a decade.

A dearth of new copper discoveries and capital spending on mine development in recent years means that once an existing mine becomes exhausted, its output may not be replaced in time to meet the growing demand.

Moreover, since 2000, most reserve additions have come from simply lowering the cut-off grade and mining lower-quality ore as prices moved higher (e.g. Chile’s Escondida copper deposit), a practice that may not be feasible for geological reasons in the upcoming cycle, as Goehring & Rozencwajg argues.

Although there will be new projects coming online (e.g. DRC, Panama and Mongolia), these will only offset depletion at other existing mines, leading to stagnant overall mine supply growth.

Acuity Knowledge Partners, formerly part of Moody’s Corp., is predicting a widening demand-supply gap that could reach as high as 8.2 million tonnes by 2030.

For this reason, exploration companies holding high-quality copper assets will appeal to investors.

Lithium

Lithium prices have taken off in China, with soaring electric-vehicle sales underpinning a more than six-fold gain over the past year.

The S&P Global Platts China Battery Metals Outlook for 2022 says China’s lithium market is set to face tightening supplies throughout 2022 as the demand-supply mismatch widens.

According to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, EV sales in the country will reach 5 million units this year, up 40% from 2021.

S&P says further demand growth in 2022 will mean a lithium deficit this year as use of the material outstrips production and depletes stockpiles.

Supply is forecast to jump to 636,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent in 2022, up from an estimated 497,000 in 2021 — but demand will climb even higher to 641,000 tonnes, from an estimated 504,000, the report said.

Beyond the short-term, there are challenges for lithium supply to expand fast enough to avoid a prolonged market squeeze over the coming years.

Skeptics point to Rio Tinto’s controversial lithium project in Serbia, now on hold due to environmental protests, and growing concerns around the sustainability of South America’s lithium brine production, as long-term threats to global supply.

Graphite

North America produces just 4% of the world’s graphite supply, from mines in Canada and Mexico. No US natural graphite production was reported to the USGS in 2019-21.

China, Brazil and Mozambique are responsible for most graphite mining, with China producing about two-thirds.

According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, the flake graphite feedstock required to supply the world’s lithium-ion anode market is projected to reach 1.25 million tonnes per annum by 2025. At this rate, demand will easily outstrip supply in a few years.

According to analysts Visual Capitalist Elements, via Battery & Energy Storage Technology, demand for graphite from battery makers is expected to expand 10.5-fold to 2030. They forecast the natural graphite market could be in deficit as early as 2023, due to a shortage of new sources outside China.

(China represents a combined two-thirds of global cathode and anode production, however when broken down, we find that 86% of anodes (natural and synthetic graphite) are produced in China, while 100% of natural graphite anodes are made there.)

Nickel

Nickel sulfide deposits provide ore for class 1 nickel users which includes battery manufacturers. These companies purchase the end product known as nickel sulfate, derived from high-grade nickel sulfide deposits. It’s important to note that less than half of the world’s nickel is suitable for the biggest growth market — EV batteries.

According to BloombergNEF, demand for class 1 nickel is expected to out-run supply within five years, fueled by rising consumption by lithium-ion electric vehicle battery suppliers.

Decades of under-investment equals few new large-scale greenfield nickel sulfide discoveries. Only one nickel sulfide deposit has been discovered in the past decade and a half, Nova-Bollinger in Western Australia.

The result of such limited nickel exploration is a very low pipeline of new projects, especially lower-cost sulfides in geopolitically safe mining jurisdictions. Any junior resource company with a sulfide nickel project will therefore be sought-after by major or mid-tier miners with the deep pockets required to build it into a mine.

Cobalt

Seventy percent of the world’s cobalt comes from the DRC. Trailing far behind in cobalt production are, in order, Russia, Australia and the Philippines.

A very important point about cobalt is that it is almost never mined on its own. A full 99% is unearthed as a byproduct of copper and nickel mining.

In 2021 the DRC produced 120,000 tonnes of cobalt, up from 98,000t in 2020. Canada mined just 4,300 tonnes and the US even less, 700t.

And while China mined a paltry 2,200t in 2021, the country is the world’s leading cobalt refiner, getting most of its raw cobalt from mines in the DRC. China also consumes the most cobalt, with 80% used by the rechargeable battery industry, according to the USGS.

Indeed, no metal exemplifies “supply insecurity” better than cobalt. The battery metal could easily be targeted by China for export restrictions, or an embargo that would harm US end-users that depend on a reliable cobalt supply chain.

Fastmarkets recently quoted Eurasian Resources’ CEO Benedikt Sobotka saying that the market is severely undersupplied, with no discernible signs of easing. As of Feb. 4 cobalt prices were US$71,000 per tonne, an increase of 60% compared to a year ago.

Silver

According to the Silver Institute, “In 2021 mined silver production [was] expected to rise by 6% year-on-year to 829 Moz. This recovery is largely the result of most mines being able to operate at full production rates throughout the year following enforced stoppages in 2020 due to the pandemic.”

“Overall, the silver market [was] expected to record a physical deficit in 2021, albeit modestly. At 7Moz, this will mark the first deficit since 2015.”

Silver demand is only likely to strengthen, given its use in solder, solar panels, 5G, EVs, and printed and flexible electronics — not to mention steady investment demand in the form of physical silver (bars & coins) and silver-backed ETFs.

Less than 30% of silver production comes from primary silver mines, with over half sourced from lead-zinc operations, and copper mines, meaning that silver’s fortunes are tied to other industrial metals.

The prices of zinc, lead and copper have all done quite well, rising a respective 36%, 8% and 22% from a year ago.

Zinc

Like copper and nickel, zinc has clean energy applications. It can be used as anode material for batteries, making it a key part of energy storage systems as we move towards a world of renewables. Recent research also shows batteries built around zinc can be a cheaper, safer, and more effective alternative to lithium-ion batteries.

Given the current rate of consumption, it is projected that global zinc reserves — estimated by the US Geological Survey at 250 million tonnes — will only last another 17 years. The zinc market has reached a critical stage when more mines are needed. But even if all the development projects come online at full capacity, industry experts think that won’t be enough to outpace demand.

At the end of January premiums for physical zinc hit record highs, as the market scrambled for metal following the closure of a second zinc smelter due to high power costs. Reuters reported that Nyrstar placed its Auby smelter in France on care and maintenance, while Glencore closed its Portovesme zinc plant for the same reason.

Wood Mackenzie said that zinc prices in January moved about $200 per tonne higher, with spot zinc premiums surpassing all-time highs reached in 2006 and 2007. “There is little chance of a respite from high premiums in the near-term,” the commodities consultancy wrote in a January report summary.

Conclusion

Inflation is at a 40-year high, making commodities, which protect investments from rising prices and currency debasement, a good place to park your hard-earned cash.

Some investors like to play commodities by purchasing an exchange-traded fund (ETF), but we prefer to go straight into the metals we are most bullish on. Buying shares in a producer is another common strategy, however history shows that junior explorers offer better leverage to rising metals prices. And they happen to be cheap. For the most part, companies exploring for copper, graphite, zinc, nickel, lithium, silver and cobalt, have not matched soaring commodity prices.

There are so many reasons to be bullish on commodities and, a lot to indicate that inflation is not going away anytime soon, thus setting up the conditions for a multi-year commodities up-trend.

To summarize, there has been a lack of spending on exploration and development, leading to current and looming supply shortages for a number of metals. The mining companies in the mid-2010s basically ate each other and by shutting down exploration there was no accretive increase in reserves. Lower ore grades have also become a serious issue.

Natural resources are being used up faster than they can be replenished; this is another theme driving commodity prices higher. Countries that have the metals needed to fuel economic growth are guarding them more closely than previously; resource nationalism is on the rise.

For example Chile and Peru, the number one and two copper producers, are both seeking to raise the royalty tax on copper miners, while in the DRC, Africa’s top copper-mining country, the government banned the export of copper and cobalt concentrates — an action almost identical to what happened in Indonesia with nickel.

The United States needs to invest heavily in infrastructure and mining, especially critical minerals needed for the shift toward electrification and decarbonization.

On top of the structural supply issues you have continued money-printing and borrowing to pay for exorbitant social programs and pandemic relief. Both are inflationary and provide another tailwind for commodities.

The sum total might just be the greatest opportunity to invest in resource stocks in our lifetime.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.