Cobalt

2019.06.11

Our coverage of the electrification of the transportation system has been focused on lithium, so important is Li, the element, needed for batteries that power electric vehicles. But there are other metals incorporated into lithium-ion batteries, including cobalt, nickel, aluminum, manganese and graphite, that deserve our attention, too.

The most obvious from a critical metals standpoint is cobalt, considering that two-thirds of it comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and over half of the brittle, silvery-grey metal is refined in China. Very small amounts are mined in North America as by-products.

While cobalt has a range of uses, something we’ll explore below, currently the main demand driver is rechargeable lithium-ion batteries needed for EVs.

To fully understand the cobalt market, a little “grounding” in batteries is helpful.

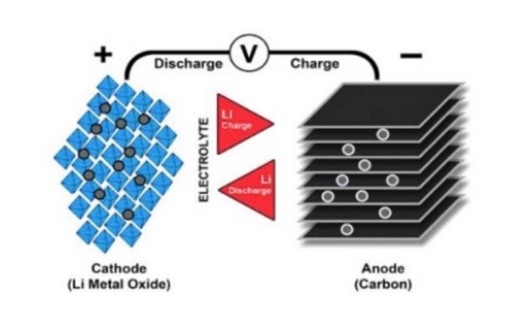

The first lithium-ion battery was produced by Sony in 1991. There are three parts to the battery: a cathode (positive electrode), an anode (negative electrode) and a conductive electrolyte. The cathode is composed of metal oxide and the anode is made from graphite. Ions flow from the anode to the cathode through the electrolyte and separator, as illustrated in the graphic below by Battery University. When the battery is charged, the reverse happens, with ions moving from the cathode to the anode.

There are several combinations of lithium-ion batteries that use different metals. These include lithium-cobalt-oxide, lithium-manganese-oxide, lithium-nickel-manganese-cobalt-oxide (NMC), lithium-iron-phosphate, lithium-nickel-cobalt-aluminum-oxide (NCA) and lithium titanate.

Cobalt is the common denominator between the two main types of EV batteries, nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) and nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM). These metal combinations are the preferred cathode materials, which range from 5% to 30% cobalt, depending on the performance, energy density, charge time, charge life, safety and cost of the battery. A typical smart phone battery contains 5 to 20 grams of cobalt, compared to an EV battery which requires between 4 and 30 kg.

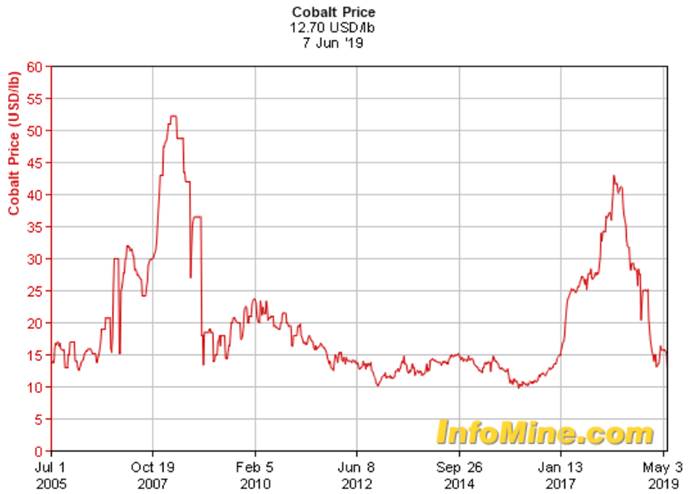

Cobalt had the hot hand in the battery metals space 2016-18, tripling in value within two years, on the strength of explosive EV growth, but prices have since dropped off, due to oversupply. We want to know, is cobalt still an investable metal? Are junior cobalt explorers on the leading or trailing edge of the trend? This article takes a deep dive into the cobalt market.

Uses

Cobalt’s properties make it a suitable metal for both metallic and chemical applications. Until recently usage was dominated by metal alloys, due to cobalt’s resistance to high temperatures, strong magnetism and wear/corrosion resistance. These characteristics make cobalt a perfect fit for aerospace superalloys, cutting tools, binders for cemented carbides, permanent magnets, prosthetics and semi-conductors.

Over the last 20 years however, the market for cobalt has shifted to chemicals, particularly compounds needed for rechargeable batteries, which represent 78% of chemical cobalt demand. Other cobalt chemicals are used in catalysts to refine petroleum, and to make plastics, steel-belted radial tires, dryers, pigments, food additives and agricultural products.

The most recent battery technology, effecting increased demand for both lithium and cobalt, is the invention of industrial and home grid energy storage systems like the Tesla Powerwall.

As mentioned, the most common lithium-ion batteries for EVs are nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) and nickel-cobalt-manganese (NMC). NMC batteries are recognized for their long-life span and high power. Apart from in EVs, NMC batteries can be found in grid storage, medical devices and power tools. High-energy-density NCA batteries are good for EVs, e-bikes, laptops and grid storage.

The chart below shows 20% of cobalt was used in lithium batteries in 2006, compared to 51% 10 years later. By 2020 the lithium-battery market for cobalt is expected to hit 62%.

The Canadian Mining Journal states that cobalt consumption for lithium-ion batteries has seen a 6% CAGR for over 20 years – driven by demand for consumer electronics (PCs, laptops, cell phones, power tools, etc.) and more recently, EV batteries. According to CMJ, batteries now account for 60% of the 125,000-tonne cobalt market, compared to 1% of the 35,000-tonne market back in the 1990s. The publication notes that demand for cobalt has been influenced by battery technology and better cathode chemistry:

Until recently, rechargeable batteries were used primarily in small portable electronic devices, including mobile phones, notebook computers, games and power tools. Growth in demand reflected a two-decade evolution in battery technology and increasing energy density from nickel-cadmium to nickel-metal hydride and to today’s lithium-ion chemistries.

Lithium-cobalt oxide (LCO) cathode chemistry, containing up to 60% cobalt by weight, is the standard cell powering small devices because it delivers the highest volumetric energy density, enabling thin batteries preferred by consumers.

Supply

The majority of the world’s cobalt comes from the DRC. The exact figure according to the US Geological Survey is 64%; trailing far behind in cobalt production are, in order, Russia, Australia and Cuba.

A very important point about cobalt is that it is almost never mined on its own. A full 99% is unearthed as a by-product of copper and nickel mining.

The USGS notes the vast majority of cobalt resources are locked within stratiform copper deposits in the DRC and Zambia. The remaining tonnage is found in nickel-bearing laterites in Australia and Cuba. Over 120 million tonnes of cobalt have also been identified in manganese nodules and crusts on the ocean floor.

In 2018 the DRC produced 90,000 tonnes of cobalt, up from 70,000t in 2017. Canada mined just 3,800 tonnes and the US even less, 500t.

Indeed, no metal exemplifies “supply insecurity” better than cobalt. Depending on foreign countries for critical battery metals like cobalt and lithium deprives Canada and the US of what is known in the mining industry as “security of supply”.

Without a reliable local supply chain, a country must depend on outsiders. This gives foreign suppliers incredible leverage. There is always the possibility of slowed flows or bans on critical minerals, due to politics or trade disputes – a perfect example being the ongoing trade war with China.

Cobalt could easily be targeted by China for export restrictions or an embargo (same as rare earths have been threatened), which would likely harm US end-users that depend on a reliable cobalt supply chain.

Ciaran Roe, global manager of metals pricing at S&P Global Platts, tells South China Morning Post: “Unlike manganese, lithium and nickel, cobalt is limited in supply not just in terms of tonnage but also origin,” he said. “I can’t think of another commodity where supply is so reliant on one origin nation than cobalt.”

A few points about the DRC are relevant here. The first is the country’s lack of infrastructure for mining. An absence of proper mines, equipment, processing facilities and trained workers has swept the cobalt mining industry to the fringes. About 15% of DRC’s cobalt output comes from unregulated artisanal mining operations – over triple the combined cobalt output of Canada and the US.

Allegations of human rights abuses including child labor have put the DRC in the wrong kind of international spotlight. BMW, Daimler (owner of Mercedes), Volkswagen and Apple are among big-name companies that source components from the DRC, and facing pressure to make their supply chains transparent.

The iPhone maker is reportedly in talks to buy cobalt directly from miners.

The second point is that China is heavily invested in the DRC, as it works towards its goal of mass EV adoption, and ensures its factories have access to clean-technology raw materials like cobalt, lithium and graphite.

In a $9 billion joint venture with the DRC government, China got the rights to the vast copper and cobalt resources of the North Kivu in exchange for providing $6 billion worth of infrastructure including roads, dams, hospitals, schools and railway links. China controls about 85% of global cobalt supply, including an offtake agreement with Glencore, the largest producer of the mineral, to sell cobalt hydroxide to Chinese chemicals firm GEM. China Molybdenum is the largest shareholder in the major DRC copper-cobalt mine Tenke Fungurume, which supplies cobalt to the Kokkola refinery in Finland. China imports 98% of its cobalt from the DRC and produces around half of the world’s refined cobalt.

Third, it’s important to note that the DRC is a country susceptible to resource nationalism. There have been several examples of foreign firms’ mining licenses being expropriated, and the government recently raised its tax on cobalt by five times, to 10% of revenues.

Demand

The demand for cobalt is directly correlated to the growth of lithium-ion batteries and electric vehicles. That growth is part of the long-term electrification of transportation trend that we at Ahead of the Herd continue to follow and invest in.

Electrification represents the shift, driven by climate change, away from fossil fuels, towards cleaner forms of energy like nuclear, solar and wind.

A few interesting facts on air pollution, courtesy of Cobalt27:

- 3 million deaths a year are linked to exposure to air pollution.

- Transportation accounted for one quarter of global emissions in 2016, 71% higher than in 1990. (We are going in the wrong direction)

- Vehicles represent about 80% of greenhouse gases.

With a focus on more air-quality legislation in cities, Stuttgart, Paris, Mexico City, Athens, Madrid, Paris are all banning diesel fuel by 2030. Norway, the Netherlands, France, Germany, UK, China and India have indicated they will ban cars running on fossil fuels.

According to an article in Seeking Alpha, stringent CO2 emissions standards starting in 2020 “are paving the way for the meteoric rise of electric vehicles.” Germany is looking at doubling subsidies for EVs costing under 30,000 euros and raising subsidies for more expensive electrics. Mercedes Benz wants to make its entire fleet of vehicles carbon neutral by 2039.

Electric vehicles are seen as a critical part of the equation to slow global warming – especially countries like China and India with their horrendous air quality.

According to Bloomberg, EV sales are expected to increase from 1.1% of the total auto market in 2017, by a factor of 10 by 2025, 27X by 2030 and 50X by 2040. JP Morgan is forecasting electric cars to be 35% of the global market by 2025 and 48% by 2030.

Whatever number you go by, this exponential jump in EVs will require a major scaling up of both battery facilities and the metals they are buying; 68 battery mega-factories are currently either under construction or planned.

The managing director of Benchmark Minerals, an industry research firm, recently told the US Senate he thinks that cobalt demand will quadruple by 2028, as EV market penetration deepens. “We are in the midst of a global battery arms race in which the US is presently a bystander,” Simon Moores said.

Benchmark projects global cobalt demand at 276,401 tonnes by 2028 – more than double the 105,000 tonnes of refined cobalt produced in 2017.

Darton Commodities forecasts a 30% increase in cobalt demand, from 93,950 tonnes per annum in 2016 to 120,000 tpa in 2020. Consider that in 2008, the cobalt market was just 50,000 tonnes a year.

Higher EV adoption rates of course will be governed by prices. EV drivetrains are expected to be cost-competitive with combustion engines within five to 10 years.

Prices

Cobalt prices have seen the largest price increase among all the battery metals used to make EV batteries. According to Roskill, standard-grade cobalt prices started the year at $26 a pound but have fallen in the first quarter, to $14 per pound in March. That’s a fair distance from the $40/lb prices reached in April of 2018.

Roskill attributed the price slide to oversupply, especially of cobalt hydroxide, clashing with sluggish demand and limited stockpiling. DRC cobalt production expanded by 44% in 2018 to 106,439 tonnes. A lot of cobalt that was not committed to long-term contracts last year added to the glut, Roskill explained.

Oilprice.com writes that several years of rising cobalt prices “brought about a rush to mine as much cobalt as possible and sell it to the Chinese,” noting that China accounts for two-thirds of the world’s lithium-ion megafactory capacity. The publication also argues that artisanal mining in DRC was a factor in over-production: “People there are literally mining cobalt in their backyards.”

However, Roskill observes that “some restocking is taking place” which should push cobalt prices back up after reaching a bottom of $14/lb in March. The metals consultancy expects prices to recover in 2019.

As to whether cobalt is currently over, or under-supplied, the market is currently in a deficit position “but most analysts believe it will be in balance or in a small surplus after the ramp up of the Katanga and Roan Tailings projects in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) next year,” Canadian Mining Journal reported.

“There is general consensus, however, that strong demand growth from electric vehicle (EV) mass adoption in the early 2020s will push the market into a sustained period of shortages until new deposits are developed.”

Reduced usage?

According to the Federation of Congolese Enterprises, cobalt prices hit a 10-year peak last April, prompting many end-users to consider reducing their cobalt usage. This has led to some speculation that cobalt may be on the chopping block for being too expensive a battery metal. Cobalt-free battery chemistries are being experimented with, and researchers/ end users are working on ways to reduce the amount of cobalt in lithium-ion batteries.

However, all the commentaries we have read point to the conclusion that cobalt is not on the way out. An editorial in The Northern Miner states that “despite the cobalt obituaries, there is an undeniable reality here: while battery manufacturers are indeed optimizing their chemistries, research suggests there simply isn’t an easy solution to eliminating cobalt from a lithium ion cell without a trade-off, such as performance or safety. Combine this with projected growth in other sectors that use cobalt (think jet engines and magnets that provide the electric motors for our new electric vehicles [EVs]) and forecasted demand for cobalt is as robust as it has been for many years, if ever.

The editorial goes on to say that it is highly unlikely that lithium-ion batteries containing cobalt will not power EVs for the next five to 10 years at least. Among the reasons to continue using it, are its relative abundance, its high energy density and its stability in the cathode metals mix. The author notes high-nickel-content batteries currently being pursued “have shown greater susceptibility to thermal runaway and overheating”, as does an NCA battery employed by Tesla whose cobalt content has dropped from 13% to just 3%.

The editorial also observes that cobalt rose to $50/lb in 2008 on the rapid spread of smart phones, but did not result in cobalt being discontinued from phones, nor did it lead to a drop in the popularity of the now-ubiquitous hand-held devices.

Simon Moores of Benchmark Minerals agrees the metal “will not be engineered out of a lithium-ion battery in the foreseeable future,” despite attempts by car makers to reduce cobalt content in their EVs.

Trade war

Donald Trump started a trade war with China thinking, obviously, that his administration could win it. Through a combination of hubris and ignorance, this president didn’t bother to find out what is America’s soft underbelly, its Achilles heel. The answer is the country’s heavy reliance on foreign supplies of critical minerals. And not just any critical minerals – the raw materials it needs to become a leader in high technology, transportation, energy and defense. Materials like lithium, rare earths, cobalt and graphite.

For years the United States and Canada didn’t bother to explore for these minerals and build mines. Globalization brought with it the mentality that all countries are free traders, and friends. Dirty mining and processing? NIMBY. Let China do it, let the DRC do it, let whoever do it.

China recognized opportunity knocking and answered the door. The possibility of the country’s main supplier becoming its enemy was far from the minds of presidents long before Trump. Now the issue is in the headlines, on China’s radar.

Americans may be buying less Chinese goods, its companies and citizens effectively paying an extra 10-25% tax that are the tariffs, but the Chinese are not worried, nor are they in any hurry to strike a deal. They “hold the nuts” as the poker expression goes.

Allow me to explain. Not only has China locked down the world’s supply and processing capacity of battery metals, lithium, cobalt and graphite it can also use currency manipulation to make its good cheaper. A 30% devaluation of the yuan would make its exports competitive again, not only to the United States, but the rest of the world. Devalue the yuan enough, and everyone will be knocking at China’s door to buy its inexpensive goods. Pretty soon China won’t even need the US anymore.

Combine a currency devaluation with continued investment in the Belt and Road Initiative and embargoing critical metals exports to the US and you see where China is going with this.

BRI is a vast network of railways, pipelines, highways and ports that would extend west through the mountainous former Soviet republics, south to Pakistan, India and southeast Asia.

So far over 60 countries, containing two-thirds of the world’s population, have either signed onto BRI or say they intend to do so. According to the Center for Foreign Relations, the Chinese government has already spent about $200 billion on the growing list of mega-projects projects including the $68 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Morgan Stanley predicts China’s expenditures on BRI could climb as high as $1.3 trillion by 2027.

The Belt and Road Initiative is seen by proponents as an economic driver of proportions never seen before in human history. It would not only allow Asia to relieve its “infrastructure bottleneck” ie. an $800 billion annual shortfall on infrastructure spending, but bring less-developed neighboring nations into the modern world by providing a growing market of 1.38 billion Chinese consumers.

Opponents argue that is naive and the real intent of BRI is to carve new Chinese spheres of influence in Asia that will replace the United States, in-debt poor nations to China for decades, and restore China to its former imperial glory.

I’m in the latter camp. Consider this: All China has to do is stop buying US Treasuries, and use their $1.2 trillion worth of T-bills to invest in Belt and Road projects. Continue to make loans to poor developing nations that want to become part of BRI, using US dollars, while the USD is still the reserve currency. The loans are paid back using offtake agreements for raw materials from these countries, which become part of the largest trading block in the world, thereby further distancing China from the West. Remember, Russia is part of BRI. The Kremlin and Beijing have already signed billions worth of energy deals, and are talking about a new payments system that allows for trade in rubles and yuan, excluding the US dollar.

Devalue the yuan, so that China’s new south Asian trading partners can buy competitively priced Chinese goods, further enslaving them with crippling trade deficits.

Meanwhile, hit back at US companies as retribution against the United States which dared to stand in the way of companies like Huawei and ZTE. Embargo their critical metals, effectively starving their supply chains, and watch them slowly wither and die.

When you think about it, it’s a beautiful plan. People thought President Xi was crazy when he invoked ‘The Long March’ to describe his 15-year battle plan with the US. Trump thinks this can all be over in time for re-election in 2020. But China has other ideas. It has the resources, the technology and the population to lay siege to the United States for a long time. Just before he made that speech in Jiangxi province, the start of the 6,000-mile trek referred to as the Long March of 1934, which preceded the emergence of the Chinese Communist Party and Mao Zedong, Xi visited a rare earths facility, giving a hint as to how this new march might begin (an embargo). He urged his comrades to dig in for the long and difficult road ahead. The symbolism was clear: China will ultimately prevail, and when it does, Xiwill be the leader of “a new China” in much the same way as Chairman Mao.

The silver lining to all of this drama would be a realization by the United States, that it must start investing in its critical metals supply chain so as to avoid China’s poisonous arrow that right now could easily sever its vulnerable Achilles heel.

Conclusion

It seems abundantly clear, after thoroughly researching the cobalt market, that reports of its imminent demise are wrong. While cobalt like all metals is subject to price volatility, and may spike if market conditions in the DRC tighten, the fact that there is no substitute, along with all its virtues as a component of an EV cathode, means that battery-makers will keep using it and mining companies will continue mining it, for the foreseeable future.

We are bullish on cobalt due to these factors and because demand for EV lithium-ion batteries containing cobalt is not going anywhere but up.

The problem with cobalt is not its attractiveness as an investable commodity, but the monopolistic market conditions it operates within. As it currently stands, the DRC controls mined cobalt supply, China runs the supply chain (taking 98% of the DRC’s production) and processes half of the world’s supply – giving the country tremendous leverage over prices and supply, just like rare earths. The US is 100% dependent on cobalt imports.

What we need is a way to break the stranglehold the DRC and China have over cobalt supply, by exploring for and investing in companies that can develop cobalt deposits in jurisdictions that haven’t locked up cobalt supply with offtake agreements, or have copper and nickel deposits with a generous cobalt by-product.

There is still plenty of cobalt to be found. According to the USGS, there are 6.8 million tonnes of cobalt reserves throughout the world. Australia has 1.2Mt, Canada has 250,000t. There are half a million tonnes of cobalt reserves in Cuba, which is gradually moving towards a market economy, 38,000 tonnes in the US, 17,000t in Morocco and 56,000t in Papua New Guinea.

Even developing one base metals mine with a significant cobalt by-product credit would help to bust the DRC-China unholy cobalt alliance.

Until this happens, we are just spectators in a cobalt game where there are only two players and one of them is gunning for total domination of the world’s natural resources.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Ahead of the Herd FaceBook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as

to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.