China IS preparing for war

2020.07.22

In 2016 Steve Bannon, President Donald Trump’s former chief strategist, declared that there was no doubt, in his mind, that the US would go to war with China in the South China Sea in the next five to 10 years.

Trump has targeted China ever since he started campaigning for president. He accused China of manipulating its currency, allowing cheap imports into the US and making American goods uncompetitive. He called out American companies that outsourced jobs to China, and complained how US firms were at an unfair disadvantage, in having to share technology with China as a condition of accessing its population of nearly 1.4 billion consumers.

Attacking the trade deficit between China and the United States would become an obsession with the Trump administration, and the sine qua non behind the trade war that Trump launched against Beijing in the spring of 2018 (the first tariffs, on imports of steel and aluminum, targeted not only China but its other trading partners, including Canada)

Arguably, these economic irritants were just the appetizer for the main course, a “Cold War II” being cooked up between the two largest economies. In a previous article we asked, is China preparing for war? Here we present evidence showing that we were right.

Cold War heating up

It is no secret that relations between China and the US have deteriorated, just today, July 22nd, we learn the US has ordered the very abrupt closure of the Chinese in Houston citing the need to “protect American intellectual property and private data.”. There is no end to the trade war, despite a “Phase 1” agreement in January, in fact Trump just signed into law a bill imposing sanctions against Chinese individuals, banks and businesses that are helping Beijing’s Hong Kong crackdown. Billions worth of import duties on either side remain. A commitment from China to buy an additional $200 billion worth of US goods will probably never be honored.

Chinese telecom giant Huawei is accused of being a trojan horse letting China spy on countries that use its 5G technology. The US has convinced other countries, most recently the UK, not to use Huawei’s 5G equipment.

And of course, the coronavirus has been front and center in an ongoing propaganda battle over who is to blame for the pandemic – with some Chinese officials saying American athletes brought it to Wuhan where it spread through a military games competition, and the US fuming that China delayed telling the rest of the world about covid-19, silenced critics who knew about it, and allowed the virus to spread beyond China via air travel.

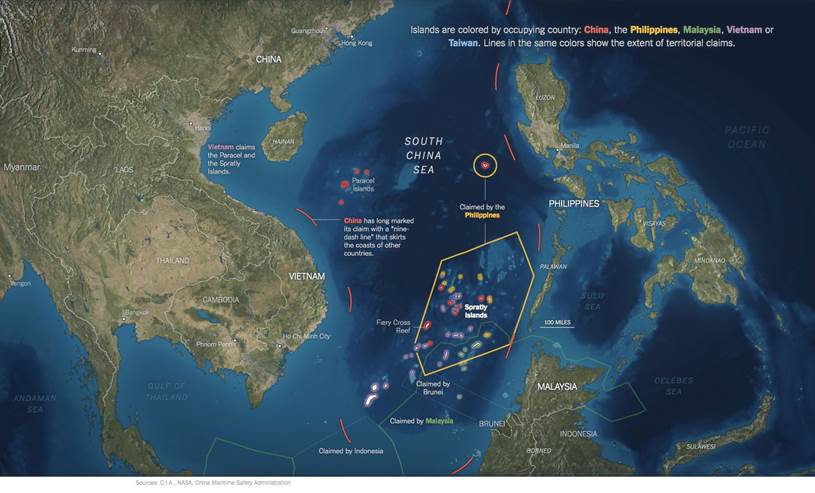

We have written extensively on the escalating tensions between the US and China in the South China Sea, where China holds historical claims despite international treaties to the contrary (ie. the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea). Ongoing maneuvers in the waters off its southern coastline demonstrate that Beijing is willing to flex its muscles in a region it sees as strategically and economically critical. China has built man-made islands and constructed port facilities, military buildings and even airstrips on them.

Last week Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea “completely unlawful” and pledged US support for countries that want to challenge Beijing.

The United States supplies weapons to Taiwan despite not having diplomatic relations with the island and its government. China sees Taiwan as a breakaway territory that must be re-united with the Chinese Mainland; its independence is not recognized by Beijing. A forced reunification would almost certainly cause a war between China and the US; the Americans would never allow Taiwan, a key tentacle of US influence in that part of the world, to be overtaken by the Chinese. Yet there are increasing calls from China to end Taiwan’s independence by the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party in July, 2021.

The anti-China feeling pervading Washington extends to US Attorney General William Barr, who recently branded Disney, Google, Microsoft, Yahoo and Apple “all too willing to collaborate” with the Chinese Communist Party; and FBI Director Chris Wray, who charged that Beijing pursues its ambitions through industrial espionage, theft, extortion, cyberattacks, and malign influence activities, CNBC reported.

For its part, China has sanctioned Senators Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio for their legislative actions linked to the detention and suppression of ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang region, and threatened to sanction US military contractor Lockheed over its defense sales to Taiwan.

As CNBC states,

All this comes in the face of an unprecedented Chinese global propaganda, economic and intelligence blitz to seize the myriad opportunities that present themselves to China as the first major economy to recover from the pandemic it unleashed. China [last] week announced 3.2% growth in its second quarter, after a 6.8% decline in the first quarter, even as the United States and Europe remain in recession.

Hard power shift

It may surprise some to see relations between the US/ Canada and China souring so badly. Wasn’t China supposed to be our friend, with an abundance of good will established through international trade, after China was let into the WTO in 2001? So what happened?

The easy answer is Donald Trump, who burst onto the scene in 2016 full of vim and vigor, ready to hit Beijing on trade, backed by China hawks like Steve Bannon and Peter Navarro. In fact it goes back further than that. The change in Chinese foreign policy came in 2012, when Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. President Xi sees himself as the leader who will reclaim China’s rightful place at the center of global power and culture, after hundreds of years of being marginalized by the West.

His “hard power” approach, by for example declaring himself President for life (eliminating term limits) territorial expansion in the South China Sea, building up the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), repressing minorities, and cracking down on Hong Kong’s desire for independence, all contrast with his predecessor, Hu Jintao, who preferred “soft power” to achieve the country’s goals.

The latter involves actions that attempt to attract, rather than coerce, other countries. Under President Hu’s tenure, they included turning Xinhua and CCTV into global media outlets; attempts to spread Chinese culture and language through its Confucius Institutes; and most importantly, lifting tens of millions of its own citizens, and client states it chose to help, out of poverty.

In a recent article, John Wong observed that [China’s soft power] includes skillful economic diplomacy and is exemplified by major regional trade agreements or expanded official development assistance (ODA) towards cooperation. David Shambaugh, one of the foremost China experts, claimed that the strongest instrument in Beijing’s soft power toolbox is money.

In fact China’s soft power diplomacy with the United States started with the secret visit of Henry Kissinger, then Secretary of State, back in 1971. Kissinger was the architect of US-Chinese engagement that, from the US perspective, sought to establish a bulwark against Soviet communism for some 45 years.

It is therefore of major significance that Kissinger, interviewed last November by Niall Ferguson in Beijing, said “We are in the foothills of a Cold War”.

In a Bloomberg op-ed, the Scottish historian wrote, Future historians will discern that the decline and fall of Chimerica began in the wake of the global financial crisis, as a new Chinese leader drew the conclusion that there was no longer any need to hide the light of China’s ambition under the bushel that Deng Xiaoping had famously recommended.

The shift from China’s soft to hard power, then, began under Xi and was encouraged by Trump, whose supporters acknowledged that the economic benefits of US-China engagement had gone disproportionately to China, under the guise of globalization, with the costs borne by working-class Americans, whose jobs had been outsourced and their wages knee-capped by overseas competition.

As Ferguson put it,

What had started out in early 2018 as a trade war over tariffs and intellectual property theft had by the end of the year metamorphosed into a technology war over the global dominance of the Chinese company Huawei Technologies Co. in 5G network telecommunications; an ideological confrontation in response to Beijing’s treatment of the Uighur minority in China’s Xinjiang region and the pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong; and an escalation of old frictions over Taiwan and the South China Sea…

It is also remarkable to see US antipathy for China cutting across both sides of the aisle:

In this context, it is not really surprising that American public sentiment towards China has become markedly more hawkish since 2017, especially among older voters. China is one of few subjects these days about which there is a genuine bipartisan consensus. It is a sign of the times that Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden’s campaign clearly intends to portray their man as more hawkish on China than Trump. (Former National Security Adviser John Bolton’s new memoir is grist to their mill.) On Hong Kong, Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic speaker of the House, is every bit as indignant as Pompeo.

There is little doubt that China senses America is weak under Trump and is therefore seeking to press its advantage, amid the lingering coronavirus crisis, and Trump’s ‘America First’ policy. The President has repeatedly criticized NATO members over funding, and recently pulled the US out of the World Health Organization in the middle of the pandemic.

His administration, influenced by the Republican Party which has a reputation for abandoning allies, withdrew US troops from the Syria-Turkey border, effectively endorsing a Turkish assault on the US-allied Kurds occupying northern Syria. Beijing suspects that Trump is just as unwilling to come to the aid of the Taiwanese should the PLA navy invade the island. Sensing a free hand, the country is therefore becoming more belligerent.

Under the cover of the coronavirus fog, China has stepped up its repression of its ethnic Muslim minorities, tightened its grip over Hong Kong, increased its pressure on Taiwan, stepped up tensions in the South China Sea, escalated attacks on Australia for seeking a coronavirus investigation, heightened pressure on Canada for detaining a Huawei executive, unleashed fatal force on the border of India and ratcheted up its propaganda against the United States.

World trade fakery

China can claim superiority over the US by being the first of the major world economies to come out of the coronavirus, returning to economic growth of 3.2% in the second quarter, versus a 4.8% US GDP decline in the first quarter, and an expected double-digit drop in Q2.

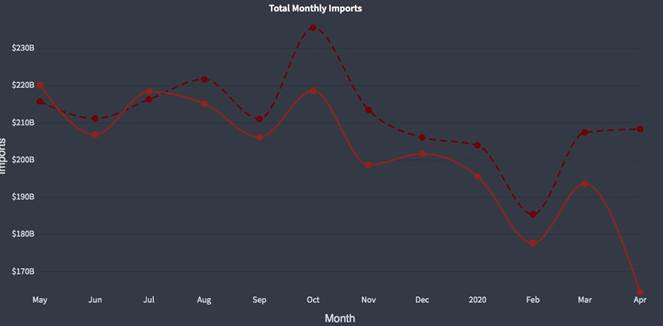

But China’s numbers don’t add up. How can China’s economy, and its exports, be growing, when none of its trading partners are buying much of anything?

The Chinese government would have you believe that neither its imports nor its exports took much of a hit from the coronavirus this year. In fact nothing could be further from the truth.

At the beginning of June, customs data from the world’s second largest economy showed a 3.3% drop in exports in May compared to a year ago, while imports plunged 16.7%. The reduction in shipments suggests weak demand abroad, with dozens of countries still hampered by government-imposed lockdowns and/or social distancing measures. You might as well chuck out China’s order book in April – nobody was buying.

The slide in imports suggests domestic demand in China is sluggish.

Getting accurate figures from the Commerce Ministry is always challenging; more often than not, they are made to suit Beijing’s purposes.

Wolf Street caught the Chinese government in a lie when the site examined world trade figures in March and April.

The first thing Wolf Richter notes is that world trade in goods fell 12% in April compared to March – the largest month to month drop in the history of the Merchandise World Trade Monitor, going back to 2000.

Yet according to China’s official data, imports and exports hardly moved, despite exports from the US and the Eurozone, and all of the major countries and regions, plunging in April. How can this be? Wolf Street states,

This contradicts absolutely everything else we know about trade with China, including what major container carriers have said, and how they have slashed capacity to and from China as trade between China and the rest of the world spiraled down. But miraculously, it doesn’t show up in China’s official data:

Our research uncovered some other startling facts.

We know that Beijing’s lockdown of millions in Hubei province, combined with widespread testing and contact tracing, managed to avoid a recession. Industrial production, a gauge of manufacturing, mining and utilities, rose 4.4% in May and 4.8% in June.

Earlier this month, surges in Chinese imports of copper and iron ore kicked up prices of those metals to multi-year highs. Unwrought copper imports (anodes and cathodes) increased 50% in June compared to May, while shipments of copper concentrate were up 8.4%, year on year. On July 14, iron ore prices hit a three-year high, as imports leapt 17% between May and June, to 101.7 million tonnes, the highest level since October of 2017.

Such increases in raw material imports should show up as exports, somewhere in the Chinese economy. Iron ore is a necessary ingredient in steel, copper is used in electrical wire, roofing & plumbing, and industrial machinery. You would think that Chinese copper and steel exports are reflected in other countries’ imports of these materials. Yet they are not. And there is no evidence that copper and steel are being used to a large extent domestically, to build more “ghost cities”, or to construct Belt and Road infrastructure.

According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), a data visualization platform, in April – the latest figures available – China exported $177 billion and imported $153 billion, leaving a trade surplus of $24.3 billion. Its year on year exports increased 4%, from $170 billion to $177 billion. Imports decreased 9.3%, from $168 billion to $153 billion.

In April 2020, China shipped mostly computers, telephones, cloth articles, integrated circuits and refined petroleum, mostly to the United States, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and Germany, in that order.

However, in all of these countries, one-year imports (May 2019 to April 2020) are shown falling.

Who exactly is China selling to, and what are they shipping?

Part of the answer is the dramatic rise in medical equipment sales, as China went on a public relations campaign blitz to portray itself as the good guy in the pandemic – the savior providing life and death PPE and ventilators to hard-hit countries.

“The recent acceleration in export growth of anti-epidemic materials contributed considerably to China’s exports,” Bloomberg quoted China International Capital Corp (CICC) analyst analyst Liu Liu. Export of textile products jumped 25.% in the first five months of the year, the second-largest export after mechanical products.

In May, China’s trade surplus hit a record $62.93 billion, as imports plunged 16.7%, compared to a year earlier, and exports fell by a less-than-anticipated 3.3%.

Total exports to the United States fell 1.2%, those to India slumped 51%, and Brazil’s were down 26%, due to those countries’ battles to stem the spread of covid-19, Bloomberg said:

Foreign demand for Chinese goods cooled off in May, a sign that the coronavirus-driven global slowdown is weighing on the world’s second-largest economy even as it reports stronger business activity at home… The slowdown is fuelled by lukewarm demand from China’s trading partners. South-east Asia, the top buyer of Chinese goods, reported a 1 per cent dip in imports from China last month following an 8 per cent increase in April, as a resurgence in the pandemic took a toll on local demand. Exports to the US and Europe fell respectively 11 per cent and 1 per cent in the first five months of this year as western countries struggled to reopen their economies despite a drop in virus cases. China’s exports overall rose just 1.4 per cent year on year last month following an 8.2 per cent jump in April and a 13.3 per cent drop in the first quarter.

Exports are not seen picking up, as China moves through its summer construction slowdown – stripping away a key driver of copper’s recent rebound, Reuters reports:

“Orders in June were lower and we expect them to be worse in July. June to August are seasonally weak,” said a copper rod maker in Guangdong whose plant ran at full capacity in March and April and at a slightly lower rate in May.

Export orders for copper-rich goods such as air conditioners from outside China remain weak, even as countries start to emerge from COVID-19 lockdowns.

“From mid-May to now – and we think it’s going to continue for the coming months or so – is the slowing of demand,” said Yanting Zhou, an analyst at consultancy firm Wood Mackenzie.

Naval buildup

So if China’s exports have been driven by shipments of medical equipment, not copper and steel-rich products as one would expect, given the robust GDP and export figures, where is all that copper and iron ore going? Obviously we can’t say for sure, given China’s opaque statistics, but we suggest a good chunk of the materials are going into bulking up the Chinese military, in particular its navy patrolling the South China Sea.

China began building up its military in the mid-1990s, with the goal of keeping its enemies at bay in the waters off the Chinese coast. Claiming territory and building islands in the South China Sea was a way of creating a wide buffer zone to defend primarily against the United States, which sees itself as the defender of international law. The US has important strategic interests in the region, with major military bases in Japan, the Philippines and South Korea.

The region is also a critical shipping lane – roughly half a billion people live within 100 miles of the South China Sea coastline and shipping volumes have skyrocketed – and hosts a wealth of fisheries, oil and gas. According to the World Bank, the South China Sea holds proven oil reserves of at least 7 billion barrels and 900 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The Council of Foreign Relations says in December 2012, China’s National Energy Administration named the disputed waters as the main offshore site for natural gas production, and a major Chinese energy company has already begun drilling in deep water off the southern coast.

Long seen to be inferior to the powerful US Navy, including the Japan-based 7th Fleet, in just over two decades the People’s Liberation Army has amassed one of the largest navies in the world. According to an in-depth Reuters feature on the Chinese military buildup,

China now rules the waves in what it calls the San Hai, or “Three Seas”: the South China Sea, East China Sea and Yellow Sea. In these waters, the United States and its allies avoid provoking the Chinese navy.

This increased Chinese firepower at sea – complemented by a missile force that in some areas now outclasses America’s – has changed the game in the Pacific. The expanding naval force is central to President Xi Jinping’s bold bid to make China the preeminent military power in the region. In raw numbers, the PLA navy now has the world’s biggest fleet.

Shipyards in China recently launched the navy’s first two Type 075 amphibious assault ships, which will play a role similar to that of the US Marine Corps, giving them the ability, with supporting weapons, to fight in distant conflicts. The 40,000-tonne ships are like a small aircraft carrier with accommodation for up to 900 troops, heavy equipment and landing craft. First renditions are expected to carry up to 30 helicopters, with later versions expected to carry fighter jets like the US F-35B. A third Type 075 is under construction and the navy could eventually have seven or more of these ships, according to China’s official military press.

The PLA is also reportedly building a fleet of smaller, Type 071 amphibious ships, with the ability to hold four hovercrafts, four or more helicopters and troops on long-distance deployments. Each 210-meter-long, 29,000-tonne vessel has a range of 10,000 nautical miles and can reach speeds up to 25 knots.

According to an analysis from the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies, China has launched more warships, submarines, support ships and amphibious vessels than the entire number of ships serving in the UK fleet – a total of 400 warships and subs. This compares to 288 US warships and subs.

In June, a Type 056 (Jingdao)-class corvette entered service, one of more than 50 such ships. It is thought to have joined the 16th frigate squadron, which already operates four Type 056 and two anti-submarine warfare (ASW)-capable Type 056A corvettes, according to Janes.

China is also expanding its marine forces, estimated at between 25,000 and 30,000 troops, compared to just 10,000 in 2017. The Pentagon and other Western military experts however say the PLA marines are less capable that the 186,000-strong US Marine Corps, which has extensive experience in amphibious and land operations.

Also, while China has established dominance close to its coast, the US Navy is considered to have more powerful ships and maintains overall dominance at sea, Reuters states, although the rivalry between the world’s two most powerful navies is growing sharper.

On June 22 Janes reported, The number of Chinese government vessels spotted in the contiguous zone of the Japanese-controlled but Chinese-claimed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands hit a record high between January and the end of May, with China Coast Guard (CCG) vessels now also maintaining a continuous presence in those waters since mid-April.

The amphibious ships and forces are expected to contribute to the PLA’s mounting capacity to make a landing on Taiwan, or other strategically important/ disputed territory.

Reuters states,

The ruling Communist Party has long wanted control of Taiwan for political reasons. The island also has huge strategic importance. It would give the PLA a key foothold in the so-called first island chain, the string of islands that run from the Japanese archipelago through Taiwan, the Philippines and on to Borneo, enclosing China’s coastal seas. From bases on Taiwan, Chinese warships, strike aircraft and missiles would dominate the sea lanes vital to Japan and South Korea. And Taiwan would be an ideal jump-off point for operations aimed at seizing further territory in the island chain…

For the United States, the stakes are now much higher in any operation to support its regional allies, including Japan and Taiwan. America now faces daunting obstacles to any efforts to reinforce heavily outgunned Taiwan in a crisis…

In November, a bipartisan commission set up by Congress to review the Trump administration’s national defense strategy reported that in a war with China over Taiwan, “Americans could face a decisive military defeat.”

US counters

Meanwhile the US wants to shore up its missile capabilities in the Asia Pacific region, following a decision to pull the country out of the Cold War-era INF Treaty, which prevented the US and the Soviet Union from acquiring intermediate-range nuclear missiles. China was not part of the treaty.

According to a May Reuters article, the Trump administration is planning to arm its Marines with versions of the Tomahawk cruise missile now carried on US warships:

The U.S. moves are aimed at countering China’s overwhelming advantage in land-based cruise and ballistic missiles. The Pentagon also intends to dial back China’s lead in what strategists refer to as the “range war.” The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), China’s military, has built up a huge force of missiles that mostly outrange those of the U.S. and its regional allies, according to senior U.S. commanders and strategic advisers to the Pentagon, who have been warning that China holds a clear advantage in these weapons.

And, in a radical shift in tactics, the Marines will join forces with the U.S. Navy in attacking an enemy’s warships. Small and mobile units of U.S. Marines armed with anti-ship missiles will become ship killers.

The Pentagon is also moving to boost the firepower of its existing strike aircraft in Asia, with US Navy Super Horner jets and Air Force B-1 bombers being armed with Lockheed Martin’s new Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile.

Budget documents show the Pentagon is seeking $224 million to order next year another 53 of these missiles, each of which carries a 450-kg warhead capable of steering itself, and striking targets at distances greater than 800 km.

Congressional leaders are currently deliberating a $3.6 billion bill to counter Chinese aggression in the Pacific, according to Defense News.

Will it be enough to hold back the ever-strengthening Chinese navy? Recent war games conducted by the Pentagon are not cause for optimism. In a series of scenarios, including clashes in the South and East China Seas, and an all-out war in 2030, the US came out second best every time.

“The 2020s will see greater risk as China begins to get the capability to challenge the US at sea and in the air (also in space and in cyberspace),” the New Zealand Herald quoted Dr. Malcolm Davis, an analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). “That could tempt it to make moves in the South China Sea and against Taiwan. The US may not be ready to meet that challenge.”

“The main challenge the US faces is sustaining the ability to project military force deep inside China’s anti-access and area denial (A2AD) perimeter – which is expanding as the PLA introduces new long-range strike capability,” Dr. Davis told News Corp today. “Carrier-based airpower, in particular, is being challenged.”

Conclusion

Once thought to be a remote possibility, I now believe there will be a war between the United States and China over Taiwan within the next two years.

China has been surreptitiously building its military, especially over the last few months – as the coronavirus distracts the world’s attention and China portrays itself as a model for countries to follow, in coming out of the pandemic with healthy exports and a growing GDP.

The Chinese leadership realizes the US is weak, with respect to its failed coronavirus response, political polarization, race riots, Trump’s unpopularity, and falling economic growth.

We can’t know China’s true economic data, but our analysis shows the numbers don’t add up. China’s exports are down, its buyers are still in lockdown or recovery mode, yet they are importing record amounts of iron ore and copper. Where is the metal going? Naval shipbuilding seems like the obvious source.

The Chinese navy is now large enough to challenge the US Navy, although a fight between the two nations might still see the US on top, due to experience and fire power. The Pentagon is reviewing its missile capabilities in the Pacific and asking for millions more to offset the Chinese advantage in intermediate-range capabilities. Congress is getting the Pentagon to draw up plans to counter Chinese aggression.

Seven Chinese fighters in less than two weeks approached Taiwan’s airspace. The US Military countered Beijing’s claims in the South China Sea by holding back-to-back naval exercises in April, and flights of B-1 bombers.

China’s President Xi appears to be using the pretext of the coronavirus as a reason for beefing up the country’s defense forces in preparation for armed combat, telling the state-run Xinhua news agency,

“It is necessary to step up preparations for armed combat, to flexibly carry out actual combat military training, and to improve our military’s ability to perform military missions.”

A flurry of safe-haven demand has pushed gold higher in recent weeks, due in part to China’s shift from a ‘soft power’ foreign policy to an increasingly aggressive, militaristic stance.

On Monday, July 20, gold futures came just short of a 9-year high, touching $1,823/oz on the Comex market in New York. The yellow metal is up 19.7%, or $300 an ounces, so far this year.

The silver trade is also on a rip, on Monday vaulting 4.4% to $19.90/oz – its best performance since 2016.

As China and the US move closer to armed conflict, precious metals are among the safest investments, that also offer shelter against currency debasement.

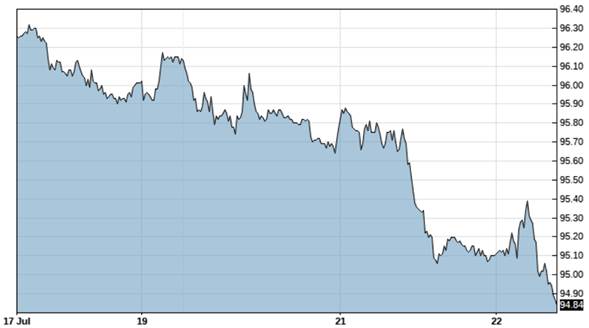

US$ Index

Current dollar weakness is directly connected to the coronavirus crisis that continues to plague the US economy, and all the measures being taken to try and limit the damage, including near 0% interest rates, trillions in fiscal spending, practically unlimited money-printing, debt out the wazoo, and the spectre of rising inflation.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Facebook

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.