China challenges US in South America with new port in Peru – Richard Mills

2024.11.22

China’s President Xi Jinping took time out of scheduled visits to South America to christen a new port on the Peruvian coast.

The $3.5 billion deep water port is in the small fishing town of Chancay, from which the port takes its name. Construction began in 2018, with the first phase finished this month.

The facility was built to provide China with a direct gateway to the resource-rich region. Key trade items include copper, blueberries and soybeans from Brazil. It also proximal to the “lithium triangle” formed by Chile, Argentina and Bolivia.

Peruvian cargo destined for Asia and Oceania currently transits through Central America or North America. To reach South America, bigger cargo ships first go to ports in the United States or Mexico and their goods are offloaded onto smaller ships.

The Peru port, built under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), will reduce shipping times to China from 35 to 23 days, cutting logistics costs by at least 20%, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said.

Majority-owned by Cosco Shipping, a state-owned enterprise, Chancay will be the first port to be controlled by China in South America. It can accommodate vessels up to 18,000 TEUs (20-foot equivalent units), the largest in the world. The ships can sail directly to and from Asia.

“The Chancay mega port aims to turn Peru into a strategic commercial and port hub between South America and Asia,” Peru’s trade minister Juan Mathews Salazar told Reuters. The publication added:

Beijing and Lima hope Chancay will become a regional hub, both for copper exports from the Andean nation as well as soy from western Brazil, which currently travels through the Panama Canal or skirts the Atlantic before steaming to China…

Peru’s government is planning an exclusive economic zone near the port and Cosco wants to build an industrial hub near Chancay to process raw materials that could include grains and meat from Brazil before shipping them to Asia.

China’s President Xi was in Peru attending the APEC Economic Leaders’ meeting, before traveling to Brazil for the G20 Summit.

Reuters reports over the last 10 years, Beijing has unseated the United States as the largest trade partner for South America, devouring its soy, corn and copper.

Peru and Brazil have both seen their bilateral trade with China expand.

China is Peru’s largest trading partner, having signed onto the Belt and Road Initiative along with at least 22 Latin American and Caribbean countries.

While Brazil has not signed onto BRI, China has been Brazil’s largest trading partner for over a decade. Brazil is China’s largest trading partner in Latin America, with the country buying Chinese goods in exchange for exports of iron ore and agricultural products such as soy.

One seasoned observer says the United States is finally paying the price for years of indifference towards its southern neighbors.

“The US has been absent from Latin America for so long, and China has moved in so rapidly, that things have really reconfigured in the past decade,” said Monica de Bolle, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

“You have got the backyard of America engaging directly with China,” she told the BBC. “That’s going to be problematic.”

Monroe Doctrine

In the 1800’s the United States under President James Monroe invoked the Monroe Doctrine, which stated that any effort by European nations to control any independent state in North or South America would be viewed as “an unfriendly disposition towards the United States.”

The intent of the Monroe Doctrine was to free the newly independent colonies of Latin America from mostly Spain and Portugal, so that the US could exert its influence undisturbed.

“The Monroe Doctrine, first articulated in 1823 as a means of blocking external interference in the Western Hemisphere, was the central pillar of US policy toward Latin America until Barack Obama’s secretary of State, John Kerry, told a roomful of Latin American diplomats in 2013 that “the era of the Monroe Doctrine is over.” The statement was part of an effort to rehabilitate the US image in a region long accustomed to seeing the United States as seeking to control it through persuasion when possible, and force when necessary. In a policy paper published [in 2016], Craig Deare, a dean at the US National Defense University and [then] Mr. Trump’s top Latin America advisor on the National Security Council staff, denounced Kerry’s statement “as a clear invitation to those extra-regional actors looking for opportunities to increase their influence. He specifically mentioned China.” — ‘Is Trump resurrecting the Monroe Doctrine?’ Max Paul Friedman

The point of mentioning the Monroe Doctrine is to illustrate just how far the United States has moved away from it. Now, the real influencer in Latin America is China, evidenced by the billions worth of investment either through the purchase of mining and energy company stakes, or outright mine acquisitions.

The reason, of course, has been to feed China’s steady appetite for commodities. As an example, the Chinese are both the largest producers and consumers of aluminum and iron ore, with iron ore imports exceeding a billion tonnes in 2023.

The enormous political, economic and cultural shift in China, from a developing agrarian society to a modern, urban one, has led to some remarkable developments, all of which are good for commodities.

The Made in China 2025 initiative, which aims to make China’s copper industry more efficient, is expected to grow Chinese copper demand by an additional 232,000 tonnes by 2025. This isn’t counting the need for more copper for railways, electric vehicles, car motors and power transformers.

While iron ore and copper have been the hot targets of overseas acquisitions by Chinese firms as they seek to feed an economy that up until 2015 was growing at double digits, the Chinese have also gone after gold, nickel, tin and coking coal. More recently the most desired metals are those that feed into a tectonic global shift from fossil fuels to the electrification of vehicles. This has meant a hunt for lithium, cobalt, graphite, copper and rare earths — metals that are used in electric vehicles, of which China has become the world leader.

The most interesting part of this trend is not that China is acquiring mines and mining company stakes abroad — that has been going on for at least a decade and a half — but that the overt attempts to lock up the world’s mining and energy resources, some of which are critical to the future world economy, are happening under the nose of the United States in Latin America, in countries previously subject to the Monroe Doctrine, right in their own back yard.

Wider implications

As mentioned the Chancay Port is part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Students of history know the original “Silk Road” refers to the ancient network of trading routes between China and Europe, which served as both a conduit for the movement of goods, and an exchange of ideas for centuries.

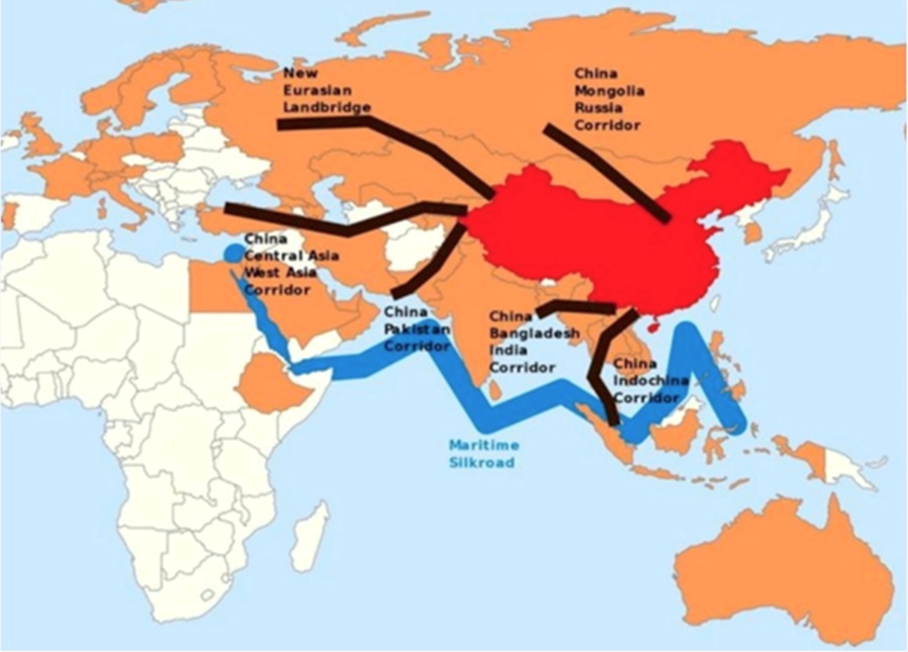

The “New Silk Road” is the term for an ambitious trade corridor first proposed by the Chinese regime under its current president, Xi Jinping, in 2013. The grand design also known, confusingly, as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a “belt” of overland corridors and a “road” of shipping lanes.

It consists of a vast network of railways, pipelines, highways and ports that would extend west through the mountainous former Soviet republics and south to Pakistan, India and southeast Asia.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, so far 147 countries —accounting for two-thirds of the world’s population and 40% of global GDP — have signed on to projects or indicated an interest in doing so.

The Belt and Road Initiative is seen by proponents as an economic driver of proportions never seen before in human history. It would not only allow Asia to relieve its “infrastructure bottleneck” i.e. an $800 billion annual shortfall on infrastructure spending, but bring less-developed neighboring nations into the modern world by providing a growing market of 1.4 billion Chinese consumers.

Opponents argue that is naive and the real intent of BRI is to carve new Chinese spheres of influence in Asia that will replace the United States, in-debt poor nations to China for decades, and restore China to its former imperial glory.

The BBC reported on the BRI’s 10th anniversary in October 2023. Among the main points in the article:

- A signature policy of President Xi Jinping, the BRI is aimed at stitching China closer to the world through investments and infrastructure projects. With an unprecedented glut of cash pumped into nearly 150 countries, China boasts it has transformed the world — and it is not wrong. But Beijing’s massive gamble hasn’t entirely gone the way it had hoped. Was it worth it?

- Most of the estimated $1tn (£820bn) has been poured into energy and transport projects, such as power plants and railways.

- China reaped a huge economic benefit in trade. A slew of agreements brought access to more resources such as oil, gas and minerals, especially as the BRI’s focus widened to include Africa, South America and the Middle East. About $19.1tn of goods were traded between China and BRI countries in the past decade. “It’s about Chinese state-owned enterprises going abroad… to help facilitate the flow of resources that China needs,” said Jacob Gunter, a senior analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies. “It’s also about expanding and developing export markets as alternatives to the liberal developed world.”

- This diversification has become crucial at a time when China faces greater tensions with the West and their allies. Take soybeans for example. China, the world’s biggest importer, used to rely heavily on the US for supplies. But a tariff war with Washington forced Beijing to turn to South American sources, especially Brazil, estimated to be the region’s largest recipient of BRI funding.

Gas pipelines from Central Asia and Russia — and oil imports from Russia, Iraq, Brazil and Oman — have reduced Chinese dependence on Japan, South Korea and the US, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). - Some critics accuse China of engaging in “debt trap diplomacy” by luring poorer countries to sign up for expensive projects so that Beijing could eventually seize control of assets put up as collateral. This was the US’ accusation over the controversial Hambantota port project in Sri Lanka.

Stop feeding the ‘Belt and Road’ Trojan horse

- Pew Research found that in the past decade many middle-income countries have increasingly favorable attitudes towards China, including Mexico, Argentina, South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria.

- China has also announced a new “digital silk road” focused on telecommunication and digital infrastructure. Analysts say this would be a more sustainable stream of profits for Chinese companies, while lessening the impact of Western bans on Chinese 5G equipment.

- But Beijing has even grander plans for the BRI, which it now touts as the foundation of “the global community of shared future”. In two white papers released [in 2023], Beijing said its form of globalization would be fairer, more inclusive and less judgmental than the one led by “hegemonic” Western powers which seek a “zero-sum game”.

Beyond Belt and Road, some see China’s heightened presence in South America in purely economic terms. CNBC quoted William Reinsch, Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, saying that “China’s own economy is slowing, and the government’s standard response to that is to try to export their way out of it. Among other things, that means looking at parts of the world that they have not yet extensively penetrated.”

Reinsch noted the Western Hemisphere has an abundance of commodities, agricultural products and minerals that China needs.

Once the Chancay Port is up and running, goods from Chile, Ecuador, Colombia and Brazil are expected to pass through it on their way to Shanghai and other Asian ports.

Brazil and China have been moving ever-closer both diplomatically and economically.

Xi and his Brazilian counterpart, Luiz Inacio Lula de Silva, this week signed nearly 40 agreements on trade, technology and environmental protection.

Brazil’s ambassador in Peru says the Chancay Port is “an opportunity for grain and meat production,” naming four Brazilian states that would benefit. He added that “Brazilian businesses are delighted with the possibility of not using the Panama Canal to take their goods to Asia,” and noted there would need to be investment in the Interoceanic Oceanic Highway which runs from southern Peru across the Andes to Brazil. A rail link is in the study phase.

According to Al Jazeera, two-way commerce between China and Brazil exceeded $160 billion last year, with the South American country sending mainly soybeans and other primary commodities to China, which in turn sold Brazil semiconductors, telephones, vehicles and medicines.

Brazil and Chile, already worried about low-cost Chinese imports undercutting local businesses, have scrapped tax exemptions for individual customers on low-value foreign purchases.

Chinese state-run newspaper Global Times says China and Latin America have promising potential for cooperation in the green and new-technology sectors, as China’s advanced new-energy technologies and products match the region’s emerging need for clean energy.

Mining deals

By far the most lucrative deals, though, have been in mining.

China has invested billions of dollars in mineral extraction in South America, particularly in lithium, copper and iron ore.

Over the past few years, overt resource grabs by China in what used to be the US backyard, countries defined by ‘The Monroe Doctrine’, include:

- Shandong Gold partnered with Barrick Gold to purchase a 50% stake in the Veladero gold mine on the Chile-Argentina border for $960 million.

- Zijin Mining acquired Colombia Continental Gold and its Buritica gold project in Colombia for CAD$1.4 billion. This was followed by the purchase of Guyana Goldfields for CAD$323 million.

- Zijin also owns the Tres Quebradas lithium project in Argentina and is building a $380 million lithium carbonate plant there.

- In 2018 China’s Tianqi Lithium purchased a 23.7% stake in Chilean state lithium miner SQM, despite concerns from regulators that the $4 billion tie-up would give Tianqi a near monopoly over the lithium market and unprecedented pricing power.

- Ganfeng Lithium owns the part of the Cauchari-Olaroz lithium mine in Argentina and bought Lithea Inc., which owns the Pozuelos and Pastos Grandes lithium salt lake assets.

- CATL won a bid to build two lithium carbonate plants in the Uyuni salt mine in Bolivia.

- CITIC Guoan and Russian Uranium One Group will build two lithium plants in Pastos Grandes, Bolivia.

- Two large Peruvian copper mines are owned by Chinese companies. Chinese state-run Chinalco owns the Toromocho copper mine, while the La Bambas mine is a joint venture between operator MMG (62.5%), a subsidiary of Guoxin International Investment Co. Ltd (22.5%) and CITIC Metal Co. Ltd (15.0%). In 2022, Chile exported $15.6B in copper ore to China.

- China owns the Marcona iron ore facilities in Peru.

- Other investments include the $1.4B Mirador copper project in Ecuador, BYD’s $299 million lithium cathode battery production facility in northern Chile, and a $400M EV battery and car factor in Jujuy province, Argentina by Chery and Gotion.

Often China’s modus operandi is to build mines in exchange for providing infrastructure that supports, and gains the favor of, the local population, such as schools, health clinics, roads and clean water systems.

The Africa model

This is the model used by China in Africa.

For example the Sino-Congolais des Mines (Sicomines) agreement was a resource for infrastructure deal that gave Chinese firms access to cobalt, copper, and other minerals in exchange for infrastructure investments. China invested roughly $3 billion into infrastructure development in exchange for Chinese firms receiving mining rights to deposits valued at $93 billion near Kolwezi, in southeastern DRC. (CSIS, ‘A Window to Build Critical Mineral Security in Africa’, Oct. 10, 2023)

The CSIS documents notes that Chinese foreign direct investment in Africa increased from $75 million in 2003 to $4.2 billion in 2020. The value of trade between China and Africa rose from $10 billion in 2000 to a record $25B in 2021, over quadruple the increase between the United States and Africa.

Chinese firms own or have stakes in 15 of 19 cobalt mines in the DRC.

Resource-backed loans are another model China has used in Africa. Loans are given to a government or a state-owned company, and repaid in natural resource off-take agreements such as oil or minerals.

After the civil war in 2002, China loaned Angola $42 billion, which supported an infrastructure boom in roads, ports, telecommunications, housing and power plants. The model worked until oil prices started falling in 2016, causing a recession in Angola that lasted five years.

At Ivanhoe Mines’ massive Kamoa-Kaukula copper mine in the DRC, 100% of initial production is split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project.

Among China’s other recent Africa mining investments,

- Shandong Gold in 2020 offered $221 million for Ghana-focused miner Cardinal Resources;

- Zijin Mining acquired a 50.1% stake in Tibet Julong Copper for $548 million.

- Privately held Yibin Tianyi Lithium Industry completed an AUD$10.7 million investment in AVZ Minerals, which has a project in the DRC.

China has also locked up rare earths and is the main player in a number of critical mineral markets including cobalt, graphite, manganese and vanadium.

In 2021, China’s Zheijang Huayou Cobalt, the world’s biggest producer of the mineral that forms part of the electric-vehicle battery cathode, said it would pay $422 million to acquire the Acadia hard-rock lithium mine in Zimbabwe.

Reuters reported in September that President Xi Jinping pledged to step up China’s support across debt-laden Africa with funding of nearly $51 billion over three years, backing for more infrastructure projects, and the creation of at least a million jobs.

At the three-year Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Summit, Xi asserted that “China and Africa account for one-third of the world population. Without our modernization, there will be no global modernization.”

Xi also called for a China-Africa network of land and sea links, Reuters said.

This year’s summit promised triple the $10 billion pledged at the 2021 summit in Dakar. This time, the financial assistance would be in yuan. The forum maps out a three-year program for China and every African state except Eswatini, which has ties to Taiwan.

According to the African Policy Research Institute, nearly two-thirds (62%) of Africa’s GDP relies on natural resources.

In 2022, China-Africa trade volume neared USD 300 billion (EUR 270 billion), tripling the trade volume between the US and African countries (Bociaga, 2023). Chinese mining and battery companies have also invested USD 4.5 billion (EUR 4 billion) in lithium mines in recent years, driving many lithium projects in countries like Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Mali. China’s investments in 15 out of 17 cobalt mining operations of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), many linked to the Belt and Road Initiative, reflects this growing dominance…

In the African mining sector, China is by far the largest buyer. In 2020, it imported about a third of Africa’s minerals and metals exports worth USD 16.6 billion (EUR 15 billion). This was an increase of 28% from 2018, highlighting China’s increasing reliance on African minerals and an opportunity for African players to leverage these resources for greater benefits.

While approximately 8% of Africa’s mining output goes to Chinese companies, 71% of African exports to China originate from just 5 countries: South Africa, Angola, DRC, Congo and Zambia. These exports are predominantly raw materials and minerals, with emerging African exporters like Guinea (iron ore), Zimbabwe (emerging in lithium), and Mozambique, contributing to the mix.

Threat to the US

Back to the Chancay Port in Peru, Reuters notes the new port embodies the challenge facing the United States and Europe as they look to counter Beijing’s rising influence in Latin America.

China overtook the US on trade in South and Central American under former President Trump, and under President Biden the gap has widened.

For example, 10 years ago, Peru traded slightly more with the United States than China. China now has a more than $10B lead in bilateral trade. The country has invested $24 billion in Peruvian mines, the power grid, transportation and hydro-electric power generation.

Interviewing two dozen officials, business leaders and trade experts, and analyzing a decade of trade data, Reuters reveals how China’s infrastructure spending is cementing its role as the key trade and investment partner for South America, defying an economic slowdown at home and U.S. warnings about debt trap diplomacy.

Part of the shift, says Reuters, is pragmatic:

Fast-growing China needs the copper and lithium from South America’s Andes, along with the corn and soy from the plains of Argentina and Brazil.

But its widening trade lead – some $100 billion around South America in the most recent annual data – brings extra clout.

Beijing has in the last year upgraded ties with Uruguay and Colombia to “strategic partnerships” – the latter a U.S. ally.

Argentina’s President Javier Milei, once highly critical of China, has softened his stance since taking office last month, reflecting Beijing’s importance to the crisis-hit economy.

It is the top buyer of Argentina’s soy and beef and has an $18 billion currency swap line with the country — which Argentina’s cash-strapped government has tapped to pay its debt, including with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

China’s trade gains have been the United States’ losses; US agricultural exporters have reportedly seen a marked decline in business to China over the past year.

The outcome of Brazil-China farm agreements is being closely watched by US agricultural interests; China is both countries’ biggest agricultural trade partner. Among the commodities in the crosshairs are meat (beef, pork, chicken), soybeans and corn.

And now with Trump about to assume a second term as president, Brazil is looking to capitalize on likely tariff escalations. While campaigning for president, Trump promised 60% tariffs on Chinese imports and up to 20% tariffs on goods from other countries.

An adviser to Trump has proposed that the 60% tariffs apply to goods from any country that pass through the Chancay Port.

The BBC notes that countries such as Peru, Chile and Colombia would be vulnerable to a Trump administration because the US could renegotiate or even scrap current free trade agreements.

All eyes will be on the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which will be up for review in July 2026.

There appears to be scant appetite on the part of the current US administration or the incoming one to put more effort into Central and South America. In fact the opposite.

The BBC notes Latin America has been seen primarily in terms of illegal migration and illegal drugs. And with Trump fixated on plans to deport record numbers of immigrants, there is little indication that the US will change tack any time soon.

While the US has been taking Latin America for granted, China’s President Xi has been visiting the region regularly and cultivating good relations. Out-going President Biden’s first and last visit to the region was at last week’s APEC Summit in Peru.

“The bar has been set so low by the US that China only has to be a little bit better to get through the door,” the BBC quoted Professor Álvaro Méndez, director of the Global South Unit at the London School of Economics.

More hawkish members of the US government are looking beyond trade at the strategic implications of the Chancay Port. General Laura Richardson, the former chief of US Southern Command, which covers Latin America and the Caribbean, says that China is “playing the long game” with its development of dual-use sites and facilities throughout the region that could serve as “points of future multi-domain access for the [People’s Liberation Army] and strategic naval chokepoints”.

More obviously, if Chancay can accommodate the world’s largest container vessels, it can also handle Chinese warships. The Chinese Navy currently patrols the South China Sea to protect what it sees as its interests including Taiwan. Imagine the US feathers just a Chinese frigate would ruffle if it tied up at Chancay.

The price of protectionism

Donald Trump won the 2024 US presidential election on a platform that promised tariffs as high as 60% on Chinese-made goods.

With so many American voters marking an X beside Trump, implicitly supporting unprecedented protectionism, it’s worth analyzing whether tariffs are beneficial to consumers, which make up two-thirds of the American economy, or not.

According to Project Syndicate, while some economists view tariffs as beneficial because they are essentially a consumption tax (more efficient than income taxes), others argue they have major drawbacks.

These include distorting markets by shifting resources from more efficient producers to less efficient domestic firms. They are also regressive, because they place a heavier burden on low-income households that spend a larger share of their income on consumer goods.

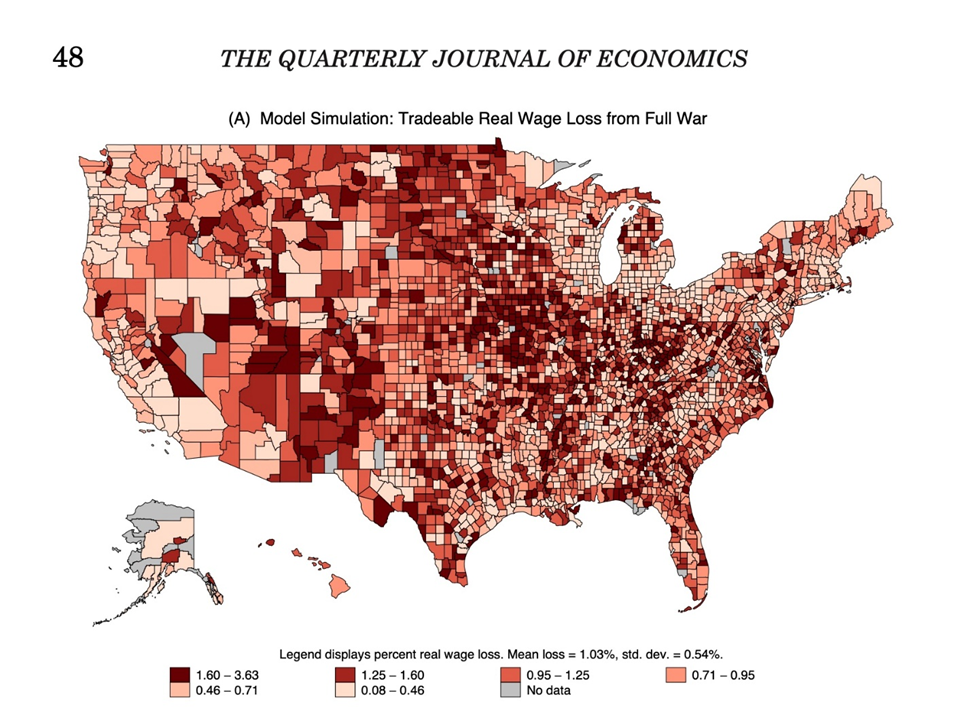

A study on the effects of the 2018-19 tariffs shows that US consumers bore most of the cost:

The resulting losses to U.S. consumers and firms that buy imports was $51 billion, or 0.27% of GDP. We embed the estimated trade elasticities in a general-equilibrium model of the U.S. economy. After accounting for tariff revenue and gains to domestic producers, the aggregate real income loss was $7.2 billion, or 0.04% of GDP. Import tariffs favored sectors concentrated in politically competitive counties, and the model implies that tradeable-sector workers in heavily Republican counties were the most negatively affected due to the retaliatory tariffs.

Conclusion

The United States is becoming more insular and protectionist at the same time as China is becoming more outward-looking.

This is no coincidence.

Beijing is no longer the economic tiger it once was, with lower growth stemming from a property crisis that has had a ripple effect on the economy and financial markets.

It sees opportunity in Latin America, a region that the US has ignored. The trade is two-way, with emerging economies like Brazil, Chile, Argentina and Colombia demanding Chinese low- and high-tech products, in exchange for metals like copper and lithium, and agricultural products such as soy and corn.

The new Chancay Port in Peru embodies the challenge facing the United States and Europe as they look to counter Beijing’s rising influence in Latin America.

Yet instead of reaching out, US leadership isn’t doing anything to shelter these countries from 20% cross-the-board tariffs, they aren’t making diplomatic visits, and they’re lumping their people among illegal immigrants and those smuggling drugs across the border.

The border issue is important to many Americans, particularly those living in states close to it, but it’s also part of a four-year election cycle – most of the 11 to 13 million immigrants slated for deportation have been in the US for over a decade.

In contrast, the Chinese think long-term, i.e., in decades, not presidential terms. Their five-year plans always have an end goal in line with meeting the objectives of their carefully laid out, and closely monitored, 25 year plans, and with respect to their Belt & Road initiatives and Latin America the goal is altering global trade routes to achieve world trade domination.

The United States thinks it will be stronger by protecting its own industries and workers with high tariff walls. What it doesn’t realize is that China has already figured out a work-around: it’s the Chancay Port and regional transportation infrastructure that funnels export goods from neighboring countries into a central point on the Peruvian coast for a direct link to Shanghai and other Asian ports.

It effectively cuts North America out of the game, and that is huge.

Some may say, “the US is the largest economy, so who cares?”, but think about how many mines that China already has already bought or has taken part ownership in, in exchange for offtake agreements.

China years ago started purchasing mines in Africa, and they soon moved onto South America when they realized the potential for locking up future-looking metals like copper and lithium.

Remember, China’s modus operandi is to build mines in exchange for providing infrastructure that supports, and gains the favor of, the local population, such as schools, health clinics, roads and clean water systems. They’ve done it in Africa and now they’re doing it in South America.

America’s answer to a lack of critical mineral supplies at home is “friend-shoring” agreements with countries such as Canada, those in Europe and yes, Latin America. But China is moving in on South America and pretty soon the US won’t have any southern friends with the resources it needs to buy from.

Central and South America increasingly sees North America as a threat and China as a friend.

Even “Mr. Nice Guy” Canada is playing defense on potential US tariffs and their consequences. Recently, Ontario Premier Dog Ford called for a bilateral trade deal with the United States, leaving Mexico on its own for separate negotiations. The Globe and Mail reported this week that all the provincial premiers support Ford’s approach to Mexico.

The Trump administration is concerned that Mexico is a “back door” for cheap Chinese auto parts and is demanding that Mexico match new Canadian and US tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, per The Globe.

How much longer before Mexico starts making overtures to its Latin American brethren, by letting up transportation infrastructure that allows it to export to free-trading China instead of tariff-happy United States and Canada?

Subscribe to AOTH’s free newsletter

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Share Your Insights and Join the Conversation!

When participating in the comments section, please be considerate and respectful to others. Share your insights and opinions thoughtfully, avoiding personal attacks or offensive language. Strive to provide accurate and reliable information by double-checking facts before posting. Constructive discussions help everyone learn and make better decisions. Thank you for contributing positively to our community!

1 Comment

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

#tariffs #protectionism #lithiumtriangle #Chancay #BeltandRoad #SilkRoad #trade