China aiming to tap US$23 trillion energy transition market – Richard Mills

2023.12.21

China, the world leader in electric vehicles and battery production, is moving forward rapidly on its plans to electrify and decarbonize.

President Xi Jinping in 2020 announced the country is aiming for carbon neutrality by 2060. (carbon neutral means emitting the same amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as is offset by other means). The country says it will boost the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25% by 2030.

The Made in China 2025 initiative seeks to end Chinese reliance on foreign technology by investing in a number of key sectors, including IT and robotics.

Both MIC2025 and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are part of Beijing’s most recent Five-Year Plan, which calls for developing and leveraging control of “core technologies” such as high-speed rail, power infrastructure and new energy, all of which require extensive minerals.

Now that China has secured most, if not all, of the minerals it needs to create what is essentially its own trading ecosystem, or sphere of influence, with BRI member countries, the work is beginning on how to build a manufacturing base from which to generate a huge range of products to sell to them.

It’s important to recognize that these aren’t the Chinese goods of old. No more cheap plastic toys and kitchen appliances. Walmart is reportedly importing more goods from India and reducing its reliance on China as it looks to cut costs and diversify its supply chain:

The world’s largest retailer shipped one quarter of its U.S. imports from India between January and August this year… compared with just 2% in 2018.

The data shows that only 60% of its shipments came from China during the same period, down from 80% in 2018.

Statements from China’s leadership indicate the country is moving into high-technology sectors that will lead the world and relegate the US to second place.

In describing the ‘14th Five-Year Plan’, President Xi indicated that China will move away from its previous economic trajectory. The plan outlines a number of policies that are designed to support the development of scientific research and advanced manufacturing.

According to the Hong Kong Trade Development Council, the Chinese government is looking to target such cutting-edge fields as: artificial intelligence (AI), quantum information, integrated circuits (ICs), life and health, brain science, biobreeding, aerospace technology, deep earth and deep sea, and implement a series of forward‑looking and strategic National Science and Technology Major Projects.

Property bubble burst

But this is future stuff. For a long time, China has relied on its real estate market for maintaining economic growth. An educated guess has property representing about 35% of GDP.

In 1994, regulators introduced a simple business model: sell apartments before they’re completed. There was no shortage of demand, as the country had entered a period of rapid urbanization following market reforms. Money from the sales funded a breakneck real estate expansion.

The strategy worked until about three years ago, when the government started cracking down on excessive borrowing. According to CBNC, Beijing was worried about financial instability — no doubt recalling the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the US that caused the Great Recession — and also wanted to rein in soaring property prices and curb the risks associated with rocketing debt.

The decision worsened a cash crunch at developers like Evergrande, which eventually defaulted on its obligations to debt holders in December 2021, triggering a wider crisis in the industry.

CBNC states the property sector has contracted severely as it adjusts to a collapse in demand, with construction starts falling by 2%, 11% and 39% compared to the prior year, in 2020, 2021 and 2022.

The troubles, unsurprisingly, are finding their way into lower GDP. In October the World Bank cut China’s gross domestic product forecast next year from 4.8% to 4.4%. Around the same time, the IMF said it expects China’s growth to slow to around 3.5% from 5% in 2023.

The last time the Chinese economy was growing this slowly was in 1989-90, corresponding to sanctions sparked by the Tiananmen Square crackdown.

The importance of China’s property sector is tantamount, in that housing accounts for about 70% of household wealth. But due to falling prices, the country is now experiencing a “negative wealth effect”. People are afraid to spend more and they are hoarding cash. CNBC reports household savings surged by $2.6 trillion in 2022, 80% higher than 2021.

A Reuters article paints an even worse picture, stating that,

The expectations were that once China ditched its draconian COVID rules, consumers would burst back into malls, foreign investment would resume, factories would rev up and land auctions and home sales stabilise.

Instead, Chinese shoppers are saving for rainy days, foreign firms pulled money out, manufacturers face waning demand from the West, local government finances wobbled, and property developers defaulted…

Youth unemployment topped 21% in June…

Shift to high-tech

But one should never count China out. Earlier this month, the Politburo, a key decision-making body of the Communist Party, met to discuss the economy and what it should do to spur recovery in 2024.

The conclusion drawn from various news reports is that Beijing is trying to find alternative engines of growth to replace its failing property sector.

Last month, President Xi Jinping stressed the need to promote “a new type of industrialization,” in which sectors like green technology could take the place of property. (Reuters, Dec. 19, 2023)

China’s leaders are reportedly determined to upgrade manufacturing and are steering money towards makers of high-tech products, from semiconductors to electric vehicles.

While China under Xi has sought to make itself an advanced manufacturing powerhouse, the news source says this time the government’s focus is narrower, targeting high-tech and “advanced manufacturing” as laid out in the 2021 five-year plan.

As of September 30, outstanding loans to the property sector fell 0.2% year on year but lending to the manufacturing sector jumped 38.2%.

Investment in high-tech manufacturing grew 11.3% for the first nine months of 2023, y/y, compared to 6.3% for total manufacturing investment, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

Dozens of provincial and municipal governments are granting loans directed towards green development, advanced manufacturing and strategic industries, Reuters said, including Guangdong province, which hiked lending to high-tech advanced manufacturing by about 45%; and the eastern province of Shandong, where loans to high-tech manufacturing climbed 67%.

As to what extent tech can replace the moribund property sector, the jury is still out, however according to a report from Goldman Sachs, via the Financial Times, each renminbi of “final demand” in “new energy vehicle” production generated only marginally less domestic value-added for the economy compared with the residential housing construction sector.

The report also says even as wind, solar and EV production grow to offset the decline in real estate, there would still be an average net negative 0.5% drag in China’s GDP over the next five years. But in 2027, EV production would rise to about 18 million units compared to last year’s 6.7 million, and account for about 60% of total passenger car production from about 29% in 2022.

MMT

Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT, posits that rather than obsessing about how large a country’s debt has grown, and the ongoing annual deficits that fuel debt, focus should instead be on government spending.

We know that China has big plans for high-tech manufacturing. The question is, how does China pay for it?

Calls are growing louder for the Chinese government to boost fiscal stimulus, regardless of higher debt levels, an approach that is drawing comparisons to MMT.

China will be poster child for developing countries’ MMT

Heretofore, China’s conservative economists would have rejected this unconventional economic theory.

Rather than ramping up stimulus, like the US, China’s focus has been on reining in government debt and curbing financial risks. Now this approach is being questioned.

“There’s a new understanding of debt in macroeconomics,” Bloomberg quotes a senior researcher at the National Institution for Finance and Development, a top government think tank. “Unlike the private sector, the government can continue to borrow new funds to repay old debts. The only requirement for this to go on is that interest rates remain low.”

Sound familiar? Under MMT, the US government can never run out of money. It just keeps printing it, to pay the interest on its debts, allowing it to borrow without limits. Presumably the Chinese could do the same. But first, Beijing would have to grow more comfortable with debt.

A proponent of MMT as it relates to China is Yan Liang, a professor at Willamette University in Oregon, is writing a book on the subject.

Liang begins by stating that the central bank could monetize debt by increasing loans to state-owned enterprises, or SOEs. This could bring long-term benefits, such as infrastructure creation. She notes that Chinese policymakers, unlike those on the West, are not driven by short-term economic rationales, therefore prolonged, multi-year spending programs involving strategic goals (e.g., BRI, Made in China 2025) fit well with MMT.

Like other Chinese pro-MMT economists, Liang believes the central government should take on more debt. “A lot of the local level spending could be the central government’s responsibility in terms of financing,” she said in a 2021 Q&A article.

“From MMT’s perspective, if debt is in the sovereign currency then it doesn’t really matter what the interest rate is. The interest rate is irrelevant when it comes to pay-ability of government debt.”

While some worry that money-printing by the People’s Bank of China would devalue the yuan, at a time when Beijing is cutting deals with other countries (like Russia) in its own currency to circumvent the US dollar, Liang maintains that the way to get around this is to implement capital controls — i.e., this is how China would implement MMT.

Capital controls limit the flow of foreign capital in and out of a domestic economy.

Big picture

According to US Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, the shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy is estimated to become a USD$23 trillion market by 2030. The head-shaking number means the United States will have to add 2,000 gigawatts of clean energy to its electrical grid by 2035 to meet its goal of 100% electricity from clean sources.

China already dominates the entire electric-vehicle supply chain and is a leader in solar and wind power. Why wouldn’t it want to take the next step and take a significant market share of that $23T total?

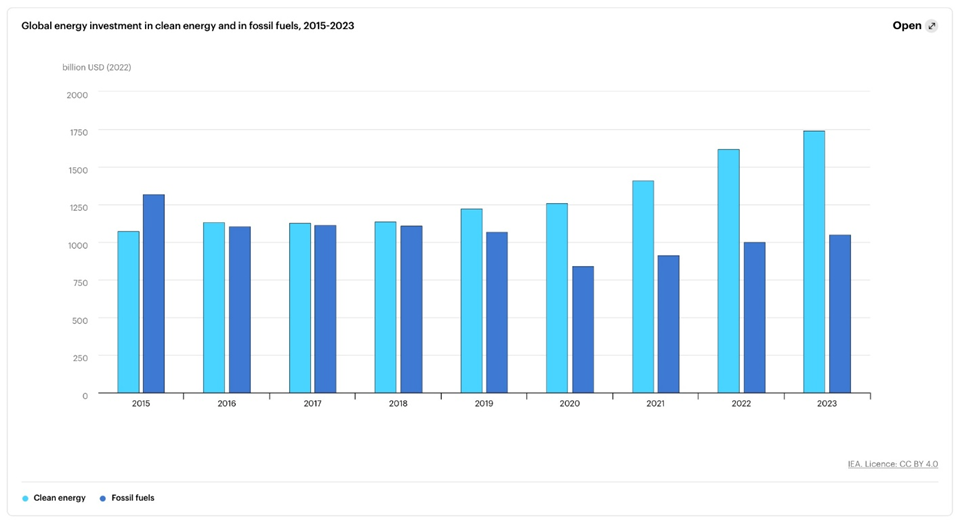

Earlier this year we reported that in 2022, the amount of money invested in decarbonizing the world’s energy system surpassed a trillion dollars for the first time. 2022 was also the first year that the $1.1 trillion which poured into the energy transition matched the $1.1T global investment in fossil fuels.

Another record: the year-on-year increase of >$250 billion (2022 vs 2021) was the largest ever jump, according to a Bloomberg story. While there has been $6.7 trillion invested in the energy transition since 2004, the article points out that it took eight years to reach the first trillion, less than four years to reach the next trillion, and under one more year to reach the latest trillion. In other words, the investment in green energy is accelerating dramatically.

Green energy investment matches fossil fuels for the first time

Updating the numbers, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said annual clean energy investment in 2023 has risen much faster than investment in fossil fuels, at 24% this year versus 15% in 2021.

The organization estimates around USD$2.8 trillion will be invested in total energy in 2023, with more than $1.7T going to clean energy including renewable power, grids, storage, low-emission fuels, efficiency improvements and end-use renewables and electrification. For every dollar spent of fossil fuels, $1.70 is now spent on clean energy. Five years ago the ratio was 1:1.

According to the IEA, clean energy investments have been boosted by improved economics during a time of high and volatile fossil fuel prices (especially since Russia invaded Ukraine — Rick); policy instruments like the US Inflation Reduction Act along with new initiatives in Europe, Japan and China; a strong alignment of climate and energy security goals, especially in import-dependent economies; and a focus on industrial strategy.

The momentum has been led by renewable power and EVs, with sales of electric cars expected to leap more than one-third this year after a record-breaking 2022. Investment in EVs has more than doubled since 2021, reaching $130 billion in 2023.

A report from Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecasts EV sales will increase to 56 million by 2040, over 9X higher than in 2021, and representing about 58% of global passenger car sales.

EV supply chain dominance

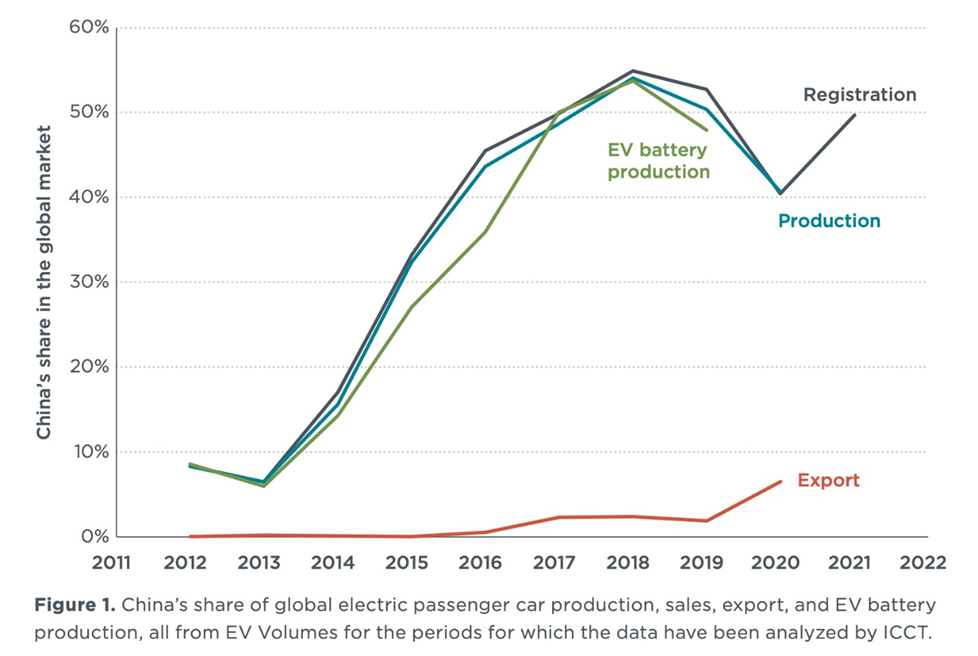

BBVA Research has some good data on China’s emergence as the global leader in the EV market. The China Association of Automobile Manufacturers reports China sold approximately 6.9 million EVs in 2022, compared to 3.3 million in 2021. Sales of non-EVs have been relatively stagnant in recent years, CAAM adds. The IEA and BNEF project that China will account for around 40% of global EV sales by 2030.

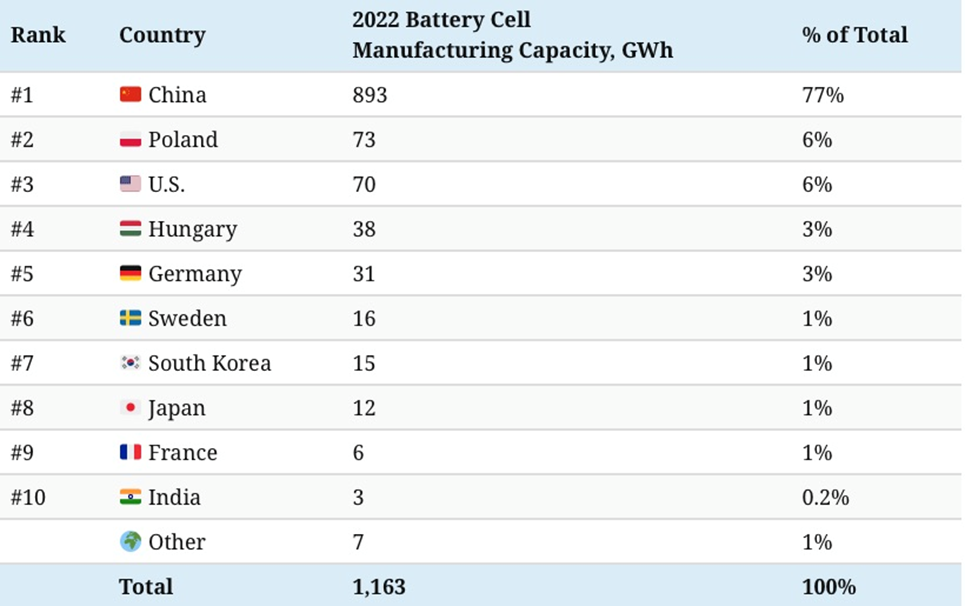

About 70% of global battery production capacity is in China, and in 2022, seven of the world’s top 10 electric battery makers were in China.

The BBVA Research report suggests China’s dominance is in part due to a national strategy that prioritizes the development and adoption of EVs. The Chinese government has implemented policy initiatives to support the production and purchase of EVs, such as tax exemptions, subsidies, and investments in charging infrastructure. Additionally, foreign automakers, such as Tesla, have been allowed to build up their factories in China.

Between 2019 and 2022, China increased its global EV market share from 30% to 41.5%, beating competitors in Europe, Japan, South Korea and North America. Japan’s and South Korea’s combined sales in 2022 were close to the 2019 level in China. Only 2.3 million EVs were sold in North America last year, compared to China’s 6.9 million.

Beyond the EV sales figures, China Briefing reports the country has more than 600,000 NEV (“new energy vehicle”)-related enterprises, with major industry players including BYD Auto, Tesla China, SAIC-GM-Wuling, Aion, and Changan Automobile.

The briefing also says China holds a dominant position in the EV supply chain, with over three-quarters of the world’s battery production capacity. The country houses more than half the world’s processing and refining capacity for lithium, cobalt and graphite. It boasts 70% of the global production capacity for cathodes and 85% for anodes.

Moreover, China’s EV manufacturing industry has a 20% cost advantage over US and European markets. This is due to government policies that support the EV industry, including subsidies and tax incentives, at the national and regional levels.

According to the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), China released its first NEV development plan in 2012; 11 years later, the country has produced more NEVs (which include plug-in, battery electric, hybrid-electric and fuel cell electric vehicles) than any other country or region.

Globally, Chinese brands account for about half of all EVs sold.

Contemporary Amperex Technology Co is the world’s largest EV automaker with 37% of market share as of the end of August. Between CATL and BYD (16%), the two Chinese companies account for more than half the battery market for electric cars.

CATL’s sales in Europe and the US almost doubled from a year earlier, said BNN Bloomberg, noting its batteries are used in Tesla’s Model 3 and Y, BMW AG’s iX and Mercedes-Benz Group AG’s EQS, in addition to powering Chinese cars.

China’s dominance in both battery manufacturing, and in procuring and processing the raw materials required for the EV supply chain, is aptly demonstrated in two tables by Visual Capitalist.

The first table shows that in 2022, China had more battery production capacity than the rest of the world combined:

With nearly 900 gigawatt-hours of manufacturing capacity or 77% of the global total, China is home to six of the world’s 10 biggest battery makers. Behind China’s battery dominance is its vertical integration across the rest of the EV supply chain, from mining the metals to producing the EVs. It’s also the largest EV market, accounting for 52% of global sales in 2021.

Poland ranks second with less than one-tenth of China’s capacity…

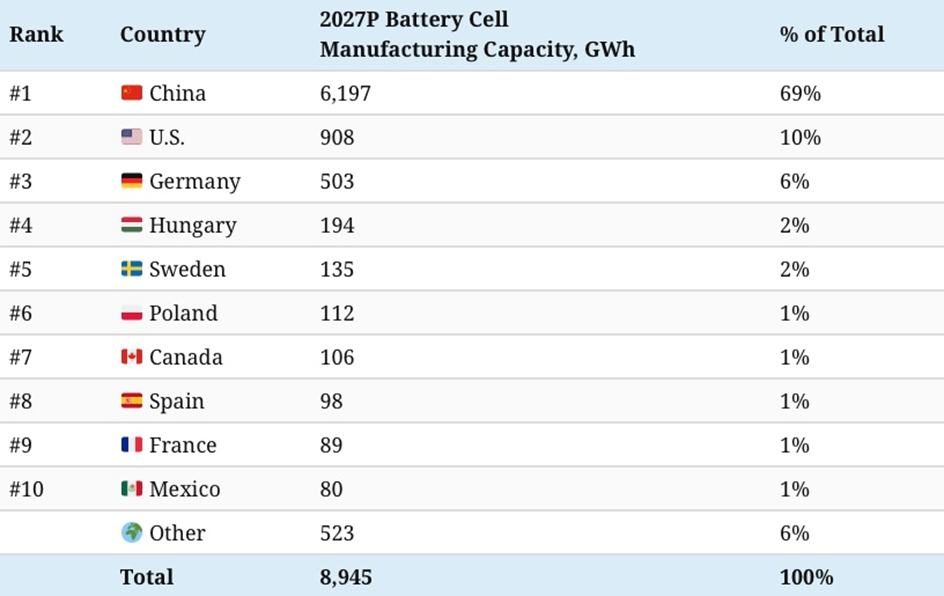

China’s well-established advantage is set to continue through 2027, with 69% of the world’s battery manufacturing capacity.

Visual Capitalist then takes a stab at determining whether the rest of the world could end China’s monopoly by 2027. It found that “regardless of the growth in North America and Europe, China’s dominance is unmatched.” That’s because most of the parts and metals that make up a battery, like battery-grade lithium, electrolytes, separators, cathodes, and anodes — are primarily made in China. Bloomberg said the US and Europe would have to invest a respective $87 billion and $102 billion to meet domestic battery demand with local supply chains by 2030.

Catching up with China is made more difficult because the demand for battery raw materials is increasing all the time, and the timeline for limiting the damages caused by global warming gets shorter.

The second table, using figures from Wood Mackenzie, shows the demand for lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) is expected to be 55% higher by 2030 in an accelerated scenario (AET), whereby the world aims to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 C by 2100, compared to the base case of 2.5 C, and 59% higher by 2050.

The table also shows the demand for two other essential battery metals, cobalt and nickel, is expected to be 16% and 26% higher, respectively, in 2050 in the AET scenario compared to the base case. Demand for graphite in an AET scenario is anticipated to be 46% higher than in the base case.

Business Insider notes that China has achieved EV leadership status by making its batteries cheaper. The country is one of the biggest producers of lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries which do not contain the relatively expensive minerals cobalt and nickel.

“What we’ve discovered in China is that electrification, and the democratization of the EV, prioritizes consumer affordability. By making it cheaper, China wins,” Bill Russo, Chrysler’s former China boss, told The Financial Times.

BloombergNEF via China Daily recently said average battery pack prices have been the lowest in China at $127 per kilowatt-hour amid intense price competition. Prices in North America and Europe are 24% and 33% higher, respectively.

NEF also said next-generation technologies, such as those applied in silicon and lithium metal anodes, and solid-state electrolytes, will further reduce prices.

Going global

The Chinese EV and battery industries have matured to the point where they are looking at serious overseas expansion.

A recent article in India’s Business Times states that Chinese EV-makers are viewing the Middle East as a major growth opportunity:

Chery Automobile is planning to launch at least two new hybrids or EVs, while Xpeng and Zhejiang Geely Holding Group’s premium Zeekr brand have started selling in Israel and making plans to expand into more countries in the region, including Qatar and Bahrain.

Other Middle Eastern countries investing in the energy transition include the UAE, Jordan, Israel, and Saudi Arabia, which this year greenlit a manufacturing plant for Ceer, its first homegrown EV brand. The kingdom has already signed a US$5.6 billion deal with premium Chinese automaker Human Horizons Technology.

BNN Bloomberg recently reported that Chinese carmakers are shipping a rising number of EVs to Europe, following failed attempts to win customers in the home of Volkswagen AG and Renault SA.

The EU accounts for about one-third of China’s EV exports. However, trade tensions are brewing. This week it was reported that the EU launched an investigation into Chinese electric vehicles. The probe could lead to import tariffs on Chinese vehicles, and countervailing duties from Beijing.

Chinese battery makers are also mulling a wider global presence. The Wall Street Journal said in October that these companies are pursuing deals with US free-trade partners South Korea and Morocco. This would allow them to bypass Inflation Reduction Act rules aimed at shutting them out of the market.

The $430-billion IRA forbids the granting of incentives to battery content and critical materials sourced from “foreign entities of concern” including China.

Chinese businesses that supply raw materials to make electric-vehicle batteries have reportedly announced at least nine joint ventures and investments worth more than $4.5 billion in South Korea this year. At least four Chinese firms said they plan to build plants in Morocco, according to WSJ.

China-based GEM said in March that it would collectively invest up to $900 million with South Korean companies SK On and EcoPro Materials to build a precursor plant in South Korea by the end of 2024.

Global Times reported that Gotion Inc. announced plans to set up battery plants Illinois and Michigan, while SVolt Energy Technology’s battery plant in Thailand has started construction.

A report from South Korean market consultancy SNE Research said Chinese companies continue to dominate the global battery power market, accounting for nearly two-thirds (62.9%) of battery installations worldwide in the first nine months of the year.

In other Chinese battery company export news:

- In September, another Chinese lithium battery maker EVE Energy set up a joint venture in the US to produce batteries used in the designated North American commercial vehicle segment, according to the company’s announcement on its website.

- Shareholders of the joint venture will be EVE Energy’s wholly-owned subsidiary EVE Energy US Holding LLC (EVEUSA), Electrified Power, Daimler Trucks and Paccar Inc., which will invest in the construction of battery production capacity.

- Gotion’s factory in Gottingen, Germany, supported by Volkswagen, is expected to reach a production capacity of 5 GWh by mid-2024 and 20 GWh when fully complete.

- In August 2022, China’s battery giant CATL announced that it will invest $7.8 billion to build a 100 GWh battery plant in Debrecen, Hungary, which is also the company’s second battery plant in Europe.

- In February, CATL and Ford reached a deal to invest $3.5 billion in an electric vehicle battery plant in Michigan, which was paused in September.

The rest of us

BNN Bloomberg says Western automakers could lose a quarter of their market share because of the rise of cheaper Chinese EVs.

UBS analysts predict China’s market share will almost double to 30% by 2030, while traditional Western carmakers will see their share fall from 81% in 2023 to 58% by 2030.

With the battery being the most expensive part of the electrical vehicle, it’s no surprise that China’s dominance is most evident in batteries. As mentioned, North American and European battery packs are 24% and 33% higher than China’s. More than 80% of EV battery cells are made in China, which processes most of the world’s lithium, graphite, cobalt, manganese and rare earths.

The Inflation Reduction Act aims to grant incentives to companies that source their battery materials in the United States or those countries with a free-trade agreement with the US, China is years ahead with its government subsidies. One example cited by Bloomberg is a national program that ran for a decade, ending in 2022, that discounted EV prices by as much as 60,000 yuan or roughly $8,375. Local governments continue to give rebates of up to 10,000 yuan.

Other advantages include direct government support, which helped launch more than 500 EV makers; and widely available (6.3 million as of the end of May) government-subsidized EV charging stations that use standardized plugs, reducing driver costs and range anxiety.

What are other countries doing in response?

According to Bloomberg, In the year after the passage of the IRA, investments totaling $55.1 billion for US battery manufacturing were announced along with $16.1 billion for EV factories. While that should eventually produce a wave of EV capacity, the immediate effect was far smaller, in part because so many US carmakers rushing to ramp up production have had to rely on Chinese technology that only 10 models now in production are eligible for the full IRA subsidy. Since the IRA was passed, Germany, France and Spain have announced a flurry of their own tax credits and aid packages for EV investments.

The European Union has set critical minerals goals but faces struggles to hit them, reads a headline this week.

The Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) aims to reduce the bloc’s reliance on China through targets, specifically that the EU mines 10%, recycles 25%, and processes 40% of its annual needs for 17 raw materials by 2030.

However, the article says a shortage of new money, crippling energy costs, and local opposition could put them beyond reach.

Moreover, the act is dwarfed by the IRA, providing just $3.3 billion of green subsidies versus $369B in the US Inflation Reduction Act.

As for Canada, a Dec. 15 Globe and Mail article asks whether Canada’s late arrival to the EV battery business will hinder its bid for “superpower” status. While Canadian companies talk about seizing “first-mover” advantage, the reality is that China’s government and industry, along with South Korea and Japan, to a lesser extent, started investing in the sector more than a decade ago:

According to the International Energy Agency, Japan’s Sumitomo Group and several Chinese companies are among the dominant players in cathode materials. A single Chinese company, Jiangxi Tinci Central Advanced Materials Co. Ltd., produces more than one-third of the world’s electrolyte salt. Chinese companies also dominate the ingredients for anodes…

According to the IEA, 70 per cent of production capacity for cathodes is in China, with South Korea and Japan playing smaller roles…

North American CAM production is negligible. As long as that remains the case, Canada faces the risk that any battery metals it eventually extracts will be exported overseas for processing…

There are at least half a dozen manufacturers worldwide that have a decade’s worth of experience making cells, according to McKinsey, and they’re mostly based in Asia.

In a report published this month by Accelerate (a coalition of Canadian manufacturers, parts suppliers, mining companies and others seeking to promote the establishment of EV battery supply chains), Marissa West, president and managing director of GM Canada, said building a battery plant here costs between three and four times as much as doing so in Asia – a reality that, in her view, highlights the need for government support.

Seemingly undeterred by these obstacles, the Canadian government has just unveiled new regulations that effectively end the sales of new vehicles powered by gas or diesel in 2035. That year, 100% of new vehicles sold must be electric.

The CBC reports that in the first three months of this year, about one in 10 new vehicles registered were electric, suggesting EV sales need to double within the next three years. They already doubled in the last three years, growing from 38,425 EVs sold in the first nine months of 2020 to 132,783 in the first nine months of 2023.

Conclusion

According to Modern Monetary Theory, if debt is in the sovereign currency, then the interest rate doesn’t matter. As long as the currency stays local, the government can always print more money to keep paying the interest.

China’s property market has tanked losing roughly a third pf its value, and Beijing is seeking “a new type of industrialization,” in which sectors like green technology could take the place of property, in the words of President Xi Jinping.

China is already the leader in the “mine-to-battery” supply chain. It dominates everything from the extraction and processing of critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite, to cell production and battery assembly, to electric vehicle sales.

It is estimated that US$1.7 trillion will be invested in clean energy in 2023 including renewable power, nuclear and electrification. The total energy transition market is pegged at an eye-watering $23 trillion.

I would bet that China is drooling at the idea of tapping into the extraordinary opportunity, in an area that it is already the market leader by a long stretch.

China has shown it is willing to put aside big dollars for subsidizing its electric-vehicle industry, which has paid dividends.

It now has an MMT model with which to raise even more funds.

In 2022, the Ministry of Finance allocated US$188 billion worth of bonds, that local authorities were urged to issue, to fund construction projects and to leverage private investment.

If China follows the MMT model, the government would buy these bonds, thus lowering interest rates, in much the same way that QE works now for Western governments. Beijing could also grant loans to SOEs (state-owned enterprises) to build infrastructure under long-term strategies such as Made in China 2025 or the Belt and Road Initiative.

MMT could be used both for building new infrastructure, and for investing in advanced high-technology to replace the declining property sector.

It all makes perfect sense and it seems to me that China has been planning to do this for a long time.

Through BRI, China will have a trading ecosystem of 155 countries. According to estimates by McKinsey and other consulting groups, between US$4 trillion and US$8 trillion will be spent on the BRI by 2049.

The other important point about China adopting MMT to pay for trillions of dollars worth of new infrastructure and high-tech industry like semiconductors and electric vehicles, is it isn’t only China that could do this. A government that pays the interest on its loans with money printed in the local currency, can borrow in perpetuity and keep adding to its debt.

Think about what this means.

A world where everybody is building new factories, power plants and beefing up their militaries, paid for with borrowed money courtesy of MMT, is commodity intensive.

If you thought supply disruptions are a problem now, just wait until China adopts MMT and other developing nations follow their model — I’m thinking India, Indonesia and many countries in Africa will be next.

The unprecedented buildup in factories, power plants, and other facilities demanded by new-economy manufacturing infrastructure, will lead to a raw commodities explosion the likes of which we’ve never seen before.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.