Champion Bear’s Eagle Rock PGE-Cu-Au project

2020.02.15

The mining of critical minerals is finally getting the attention it deserves after many years of neglect by Canada and the United States. The lack of planning to build a domestic supply chain of metals to serve the clean, green economy of the future has put North America far behind China, which has prioritized having a ready and plentiful supply of materials deemed essential to the economy and defense of a nation. End-users are often forced to deal with China and its history of restricting exports and driving up prices, as was the case with rare earths a decade ago.

Other countries also have Canada and the US over a barrel when it comes to the mining of critical minerals. Two-thirds of the world’s cobalt is produced in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). South Africa and Russia’s combined output supply the bulk of the world’s platinum group elements (PGEs). While there are smatterings of, and in a few places large deposits, of critical metals throughout North America, the number of mines are few.

This deficiency is a fact North American politicians have just woken up to, despite being a subject we at AOTH have been writing about since 2009.

On Jan. 9, Canada and the United States announced the Canada-US Joint Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration, to advance “our mutual interest in securing supply chains for the critical minerals needed for important manufacturing sectors, including communication technology, aerospace and defence, and clean technology,” reads a press release from Natural Resources Canada.

The announcement follows a June 2019 commitment by Prime Minister Trudeau and President Trump to collaborate on critical minerals.

In fact the Trump administration was ahead of Canada in pin-pointing the dearth of domestic supply and how that poses a threat to national security.

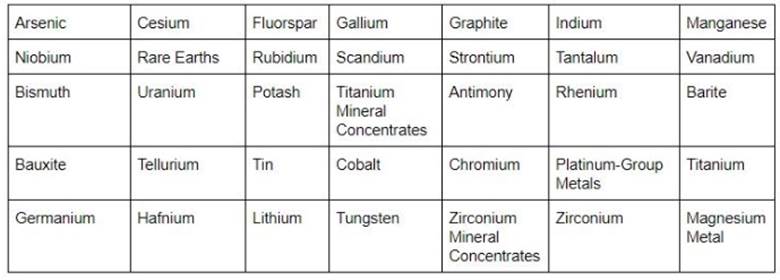

In 2017 Trump signed an executive (presidential) order to develop a strategy to ensure a secure and reliable supply of critical minerals, within 180 days. The directive was issued the day after the US Geological Survey published an updated assessment of the country’s critical minerals resources. In its report, the USGS said of 23 minerals analyzed, the US relies on foreign supplies for at least 50% of all but two: beryllium and titanium. The list was later widened to 35 critical minerals.

Global PGE supply

Platinum group metals are included among this list of mineral commodities the United States considers critical to its economic and national security. North America only has two producing platinum and palladium mines – Stillwater in Montana and North American Palladium’s (NAP) Lac des Iles mine northwest of Thunder Bay, Ontario. (In October it was announced that NAP will be acquired by South Africa’s Impala Platinum Holdings in a deal worth about $1 billion.)

Platinum, palladium and other PGEs like rhodium often occur together, or alongside other metals including copper and nickel.

Up until 1920, nearly all PGE production came from placer deposits in Russia and Colombia. The mining of platinum (Pt), palladium (Pd) and other PGEs now takes place mostly in Siberia and South Africa.

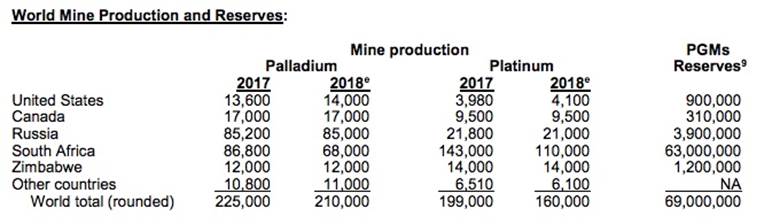

Out of 69 million tonnes of PGEs found globally, South Africa’s Bushveld Complex has the largest reserves of platinum and palladium – 63 million tonnes as of 2018, according to the US Geological Survey. Russia and Zimbabwe are a respective second and third.

South Africa is the largest Pt and Pd producer, outputting 178,000 tonnes combined in 2018, followed by Russia, at 106,000t.

Some of the most prominent platinum mines in South Africa are Impala Rustenburg, Mogalakwena, Marikana, Bathopele and Khomanani.

Most of Russia’s PGEs are mined from Norilsk Nickel’s operations, on the Taymyr Peninsula in Siberia and the Kola Peninsula. Nornickel’s mining center in the Russian high Arctic is the world’s largest producer of palladium. In 2018 Nornickel agreed to a joint venture with Russian Platinum to develop disseminated ore deposits in the Norilsk Industrial District.

The USGS notes that about 104,000 tonnes of insitu PGEs could be developed throughout the world.

What collaboration means

Cutting through the government-speak, the main points of interest to mining investors from the Canada-US Joint Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration are:

- The Joint Plan will guide efforts to secure critical minerals supply chains for “strategic industries” (undefined) and defence.

- The Canadian mining sector is setting up a task force to work with Ottawa and Washington, to identify critical minerals projects and study “how to overcome some of the R&D challenges to drive down costs and be competitive with China,” the Globe and Mail reported, quoting Pierre Gratton.

- In December Canada joined the US-led Energy Resource Governance Initiative, which aims, through multiple countries, to promote supply chains for critical energy minerals such as uranium.

- Along with Canada, the US is seeking alliances with Australia, Japan and the European Union, which also fear mineral dependency on China.

- Canada supplies 13 of the 35 minerals the US has identified as critical. They are:

“This is about the U.S. wanting to make sure it has access to a reliable supply of metals for its defence industries and manufacturing sector,” Pierre Gratton, president of the Mining Association of Canada, told the Globe and Mail.

Gratton said Canada is well-positioned to benefit from collaborating with the US, due to Canada’s strong mining industry and its integration with the US auto-making and manufacturing sectors that need these minerals.

Reducing dependence

Depending on how it is rolled out, and whether there are concrete decisions, not just platitudes, made to invest in critical minerals mining and exploration, the Canada-US Joint Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration could address the frankly embarrassing dependence North America has on overseas production of critical minerals such as platinum group elements.

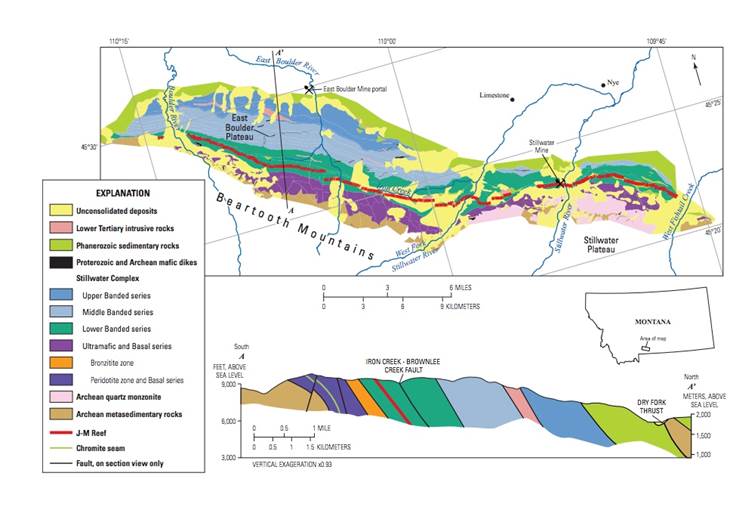

The United States is heavily dependent on external sources for PGEs, importing about 90% of the PGE metals it consumes. While small amounts are recovered as by-products of copper/ nickel mining in Minnesota, there is only one primary-PGE operation in the US, Sibanye-Stillwater’s Stillwater and East Boulder mines in Montana. Both underground mines extract PGM ore from the J-M Reef – a geological formation known to be the only significant source of PGEs in the United States, and the highest-grade Ni-PGE deposit in the world.

Canada is somewhat more independent; our country is third and fourth, respectively, among the top five countries that mine palladium and platinum.

Canadian PGEs are recovered as a by-product of nickel mining, mostly from the Sudbury Basin, as well as northern Quebec and Manitoba. About three-quarters of Canadian PGE production is sold to the United States.

The United States gets 31% of its palladium and 44% of its platinum from South Africa; Russia supplies 28% of US palladium needs.

The supply of PGEs from South Africa, the number one producer, is precarious. In 2019 platinum production fell from 4.318 million ounces to 4.201Moz, while palladium output dropped from 2.555Moz to 2.492Moz, owing to jobs cuts and mine shaft closures – a trend that is likely to continue.

“Production was expected to continue decreasing as the world’s third-leading PGM-mining company by production volume [Lonmin], announced plans to cut 13,000 jobs over the next two years at some of its mines in South Africa,” states USGS – although the company said in May it will delay or reduce the number of job losses amid higher palladium prices. Lonmin is currently being taken over by Sibanye-Stillwater which will create the world’s second largest platinum producer.

Another key factor affecting supply: Platinum mining in South Africa is frequently interrupted by labor unrest. In 2014 workers at the country’s three major producers – Lonmin, Anglo American Platinum and Impala Platinum – downed tools for five months demanding that wages be doubled. The strike was the longest and most expensive in South African history, shutting down about 40% of the world’s platinum production.

The country’s platinum miners are under constant pressure to contain costs, because their mines are some of the deepest and most labor-intensive in the world. High temperatures are also a serious issue. Platinum is being mined in reefs up to two kilometers deep, where virgin rock temperatures have been measured at 70 degrees C.

There are significant infrastructure constraints, too. The country has limited processing capacity and water is a constant concern. Recall in 2018 Cape Town came dangerously close to running out of water and was only saved from “Day Zero” by stringent restrictions on water usage.

Power in South Africa is notoriously unreliable – blackouts are frequent. In 2008 the country’s electricity grid nearly collapsed due to a shortage of coal for power stations and system faults. A year ago Eskom imposed the worst power cuts in years on homes and businesses, as the state utility grappled with another crisis within its crumbling power infrastructure.

According to Business Report, widespread power outages led to a three-month decline in mine production between August and October, with PGEs (down 4.8% year on year) among the biggest drags.

PGEs are critical metals. A relatively small amount is mined in the US and Canada – the most friendly country to the United States in the event of a supply disruption. What are the alternatives? Russia, Zimbabwe and South Africa. Russia is the target of US sanctions and a constant thorn in its side, Zimbabwe has a basket-case economy, and South Africa can’t be counted on for a reliable supply of PGEs, due to the factors we have outlined.

The US-Canada collaboration on critical minerals is particularly interesting to us at AOTH, especially the platinum group elements. A lot of attention has been focused on palladium, platinum and rhodium.

Clean and green

Smog from vehicle emissions is estimated to cause a third of the air pollution in the United States. Health problems include asthma, lung disease, heart disease, birth defects and eye irritation.

Since 1975 catalytic converters, which reduce toxic emissions from exhaust, have been mandatory for passenger vehicles. Both gasoline and diesel-fueled autocatalysts contain a mix of PGEs and other metals including platinum and palladium. A higher percentage of platinum is used in diesel autocatalysts, whereas gas catalytic converters employ more palladium.

Autocatalyst demand accounts for three-quarters of the need for palladium, for platinum it’s 40%.

Demand for palladium has surged since 2016 with the movement towards less polluting gas-fueled vehicles, aided by Volkswagen’s “diesel-gate”.

We like palladium not only for the move away from diesel, but because it will be more in demand for hybrids, which despite being cleaner than gas or diesel-fueled cars, still require catalytic converters.

Consider too, that most electric cars have a hybrid component to them. Only BEVs are pure-electric vehicles with no combustion engine. That makes hybrids a natural bridge between a conventional vehicle and an EV – not a bad thing considering that motorists still have a hard time grappling with the “range anxiety” associated with a pure EV, not to mention the logistics of finding a charging station and the high sticker prices.

A 2018 report by JP Morgan Chase & Co. predicts hybrids are expected to grow from 3% of global marketshare to 23% by 2025.

According to Nornickel, which controls 40% of the world’s palladium production, combined palladium use in hybrids (HEVs) and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) this year will be nearly triple that of 2016.

Although less demand for diesel autocatalysts has weighed on platinum prices over the last few years, an emerging market for platinum is in the manufacture of hydrogen fuel cells. Platinum is used to spur the chemical reaction of hydrogen with oxygen. Recognized as powering NASA’s 1969-72 moon landers, the process produces electricity and water. In the case of a fuel-cell electric vehicle, hydrogen is stored in a fuel tank before it is mixed with oxygen from the air.

Platinum demand for hydrogen fuel cells is set to increase into the 2020s, according to a report from Heraeus Precious Metals: “Several thousand ounces of platinum are used annually and this will grow as the technology is rolled out, potentially exceeding 100,000 ounces per year in the late 2020s.”

Their “clean and green” credentials are a key reason why we, at AOTH, are fully on board with platinum and palladium. They are a natural fit with the electrification trend we continue to follow and invest in. To summarize, palladium, platinum and rhodium are not only used in catalytic converters required for diesel/gas-powered vehicles, but much cleaner-burning hybrids. Platinum has an emerging use in hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles.

As the third-largest producer of palladium and the fourth-biggest platinum miner, Canada is well-positioned to help with electrification, by digging up the minerals required. Our country has a wealth of mining expertise, especially in Ontario’s Sudbury Basin, home to the majority of our platinum-producing mines. As prices and interest in the sector climb, several Vancouver-based juniors have popped up, keen to scour the globe for the next big PGE deposit.

Platinum market

According to the International Platinum Group Metals Association (IPA), one-quarter of all manufactured goods either contain a PGE, or a PGE played a key role in its production. That makes PGEs indispensable for industrial applications.

The chemical industry for example needs platinum or platinum-rhodium alloys to make specialty silicones and nitric oxide – the raw material in fertilizers, explosives and nitric acid. Platinum-supported catalysts are used to refine crude oil and to produce high-octane gasoline. They are also heavily applied in electronics, with PGE components utilized to increase storage capacities in computer hard disk drives, in multilayer ceramic capacitors, and hybridized integrated circuits. PGEs are needed to produce fiberglass, liquid-crystal and flat-panel displays.

Platinum and iridium’s non-corrosive qualities make them ideal for medical implants such as pacemakers, and surgical tools. Palladium, platinum and rhodium are also investment metals, bought and sold as bars, coins or ETFs.

As mentioned about 40% of the world’s mined platinum goes into autocatalysts, and an emerging market for platinum is in the manufacture of hydrogen fuel cells.

It used to be that diesel vehicles were sought after because diesel is cheaper than gasoline. Many considered diesels no worse than gas engines for air pollution. In 2016 the diesel car industry was shaken after Volkswagen admitted it had cheated on its emission tests. The “diesel-gate” scandal was made worse amid new reports of the dangers of air pollution.

The move away from diesel has hurt not only diesel-car manufacturers but platinum. Less demand for diesel autocatalysts has weighed on platinum prices, which tumbled from about $1,400 an ounce in January 2014, to a five-year low of $780/oz in August, 2018.

However platinum’s fortunes have turned considerably higher since then. Unlike palladium, platinum is a popular metal for investment purposes – like gold and silver, it is considered a safe haven in times of geopolitical or economic uncertainty. While restrained demand from diesel automakers weighed on platinum for much of 2019, investor interest helped keep the grey metal in the green, especially in the last four months of the year – as mounting geopolitical unrest pushed platinum up 17.5% for the year.

“Stellar investment demand performance is the highlight of 2019,” Paul Wilson, CEO of the World Platinum Investment Council, wrote in November. “The particularly strong investment demand in the first half of 2019 continued in Q3 and into Q4 with the increase in ETF holdings of 1 million ounces the highest seen since physically backed platinum ETFs were launched in 2007.”

On Jan. 17 platinum scaled $1,000 an ounce, an important technical milestone, even hitting a two-year high of $1,036/oz, having benefited from increased market volatility related to US-Iran tensions and the trade dispute between Washington and Beijing.

The spot price continues to stay above $1,000/oz this week, though briefly dipped below that level on Tuesday.

Palladium market

We’ve seen palladium prices more than double those of platinum, its sister metal, on tight supply and high demand for catalytic converters in gas-powered vehicles, as smog-belching diesel cars and trucks get phased out to meet tighter air emissions standards particularly in Europe and China.

Last week spot palladium ran nearly 10% to $2,539 an ounce, continuing a string of gains that has commodity traders saying the platinum-group metal has “gone parabolic”, meaning the chart pattern shows prices rising with an increasingly steeper slope.

Why the enviable price performance? Palladium has been in deficit for eight straight years, because of low mine output and smoking-hot demand for catalytic converters in gasoline-powered vehicles.

Tighter emissions regulations requiring less-polluting gasoline and hybrid vehicles will keep demand healthy but supplying all those new catalytic converters with palladium will be a challenge for the industry considering problems with South African mines.

According to a report from Sprott Asset Management, “Supply shortages continue to support palladium’s performance, with strong multi-year growth in palladium demand now straining a fixed supply.” Indeed, there is limited scope for producers to increase supply, in the near term.

Citigroup said in December that production is expected to trail consumption by 545,000 ounces this year.

Considering the difficulty the world’s largest palladium miners, especially

those in South Africa, are having increasing production, the onus is on smaller companies to find and develop new deposits of platinum-group elements.

At AOTH, we’ve recently identified a very interesting junior with a drill-ready property, in Canada, where historical exploration has shown enormous promise.

Champion Bear Resources (TSX-V:CBA), is working just south of Dryden, in northwestern Ontario. Its 100% owned Eagle Rock Cu-PGE-PM project hosts a number of sulfide showings including the Campbell Zone, which Champion Bear describes as “a continuous, predictable, PGE reef-type horizon exposed at surface over more than one kilometer.”

The 60 x 20km property sits on top of a large intrusion called Entwine Lake, host to several sulfide showings including the Campbell Cu-PGE-PM Zone, first explored by now defunct Noranda in 1969.

Seventy holes punched into Campbell defined the zone up to a depth of 200 meters, at an average width of 8m. Drilling expanded the sulfide mineralization along strike to the northwest and down-dip. The zone is open in all directions.

According to the 2011 Eagle Rock 43-101 Technical Report: “The Zone is characterized as a low-sulfide (up to 10% but typically <5% chalcopyrite + pyrrhotite), high-metal tenor horizon with typical grades of >1g/t Au+Pt+Pd and 0.5% Cu. The metal tenor of the sulphides is very good. There is a strong and consistent correlation between the abundance of copper, Au+Pt+Pd, and sulphur. There is also a very uniform relative abundance of the precious metals 2:3:5 Au:Pt:Pd as well as the base metals 6.8:1 Cu:Ni.”

With mineralization starting at surface, the company considers Campbell open-pittable, and will continue drilling it to define the nature and extent of the zone. An airborne geophysical program (HRAM) is planned, along with more prospecting and geological surveys, as Champion Bear moves towards a maiden resource estimate at Eagle Rock.

Select drill results from a 2009 program (PM’s = Au+Pt+Pd) included:

- 1.28 g/t PM’s and 0.60% Cu over 15.0m in hole ER09-14

- 2.19 g/t PM’s and 0.80% Cu over 5.0m in hole ER09-19

- 1.77 g/t PM’s and 0.61% Cu over 12.0m in hole ER09-21

- 1.32 g/t PM’s and 0.49% Cu over 8.0m in hole ER09-22

A 1,600m drill program, completed in early 2019, encountered platinum group elements in every one of the nine holes. Select drill results from the 2019 program include:

- Drill hole ER19-25 intersected 10.0 meters of 0.645 gram per tonne palladium, 0.398 g/t platinum, 0.325 g/t gold and 0.45% copper from 75.0m to 85.0m, including three two-metre-long intervals with over 0.9 g/t palladium.

- Drill hole ER19-29 intersected 56.0m of 0.488 g/t palladium, 0.272 g/t platinum, 0.188 g/t gold and 0.42% Cu from 46.0m to 102.0m.

- The palladium-to-platinum ratio for most of the intervals ranges from 1.6:1 to 1.9:1.

CEO Richard Kantor said there is reason to believe the Campbell Zone is open at depth, meaning the orebody could extend for 10s or even hundreds more meters – perhaps even as deep as the Flatreef deposit in South Africa that extends over a kilometer underground.

“We’ve got ore-grade numbers, when we go down deeper in our next program we’re hoping to hit 4-6 grams, everything’s showing there, we stopped at 198m but it’s still going. The whole thing’s mineralized,” he told AOTH in a wide-ranging interview earlier this week.

It’s important to recognize that Champion Bear is, to our knowledge, the only PGE exploration company in Canada with a “reef” type of deposit – the Campbell Zone is termed “reef-like” in that it is a relatively tabular zone consistent in terms of dip, strike, thickness, metal content, and metal tenor.

The following three diagrams demonstrate the Campbell Zone’s geological similarity to two of the biggest reef-type PGM deposits in the world – Platreef in South Africa and the Stillwater Complex in Montana.

The first image shows the Campbell Zone represented by the bold red line, running northwest to southeast and intersecting two dykes.

A similar geological cross-section is displayed in the next image, of the Stillwater Complex. Notice the red line running along the edge of the Beartooth Mountains. This is the J-M Reef.

The third image shows the Platfeef deposit in South Africa, with the thick black line depicting the Platreef sub-outcrop.

The company Kantor founded in 1987 has an interesting history that comes alive in conversation with the colorful CEO. It all started with his purchase of Plomp Farm, the second of Champion Bear’s properties. Located about 20 km from Dryden, ON, Plomp Farm occurs in two main blocks that overlie 13 km of favorable stratigraphy within the Thunder Lake assemblage.

Mineralization occurs in a broad corridor of gold enrichment, associated with pyrite and elevated silver and base metals (copper, zinc, molybdenum and barite) concentrations.

Although Champion Bear was able to obtain a $21 million financing from LOM (never exercised) to explore Plomp Farm’s strong gold-bearing system that occurs over a 2-km strike, and geologist, Chris Bradbrook of LOM, figured “it was a dead ringer for [Barrick’s nearby] Hemlo deposit,” a joint-venture deal went south around the same time as the Bre-X sample-salting scandal, which cast a pall over the entire Canadian mining industry. “We got our pants pressed real good,” Kantor recalls.

When metals prices in the late ’90’s dropped, and with Kantor paying $35,000 in advance royalties on the property, he let the claims lapse (but picked them up again 8 years later), then looked into acquiring a PGE play – seeing a bright future in what he calls “wunder metals” – palladium and platinum.

Eagle Rock came to his attention via Robert Fairservice. They spoke on the phone while acquiring Champion Bear’s third property, tantalum-rich Separation Rapids. The man who Kantor describes as a bit of a loner lived in a hotel in Kenora, must have known he was onto something big when he staked the claims, formerly owned by Noranda and BP-Selco – who were interested in Eagle Rock for its copper and gold, not platinum group elements (some of the old pits run 2-3% copper).

“He camouflaged his truck and camp, cut all the posts and at midnight he started staking,” Kantor relates. “He staked it up and I bought it from him for $20,000 + $5,000.per year advanced royalty payments for 4 years.

“He said it was a property beyond belief. We drilled it, we lost it, we got it back, it’s been a wild ride. But what he said about this property was nothing compared to what we found.”

The “wild ride” Kantor refers to is Champion Bear’s stock price which started at 6 cents a share back in the 1990s and climbed to as high as $15/sh on the potential for a takeover bid.

Kantor recalls attending a conference at the University of British Columbia with Tony Green, who at the time was running the PGE (platinum group element) department at Falconbridge, and Louie Capri, then head of the Geological Survey of Canada for PGE. The three happened to be having dinner with Hugo Dummett – a Canadian Mining Hall of Fame inductee considered to be “the brains, the ideas and the energy” behind the discovery of Canada’s first diamond deposits in the Northwest Territories, and a respected authority on copper porphyry deposits.

Capri told the dinner party that the Geological Survey had done studies at Eagle Rock confirming “everything’s got PGEs and copper, it’s just incredible.”

Capri then turned to Dummett, who owned African Minerals with Canadian mining icon Robert Friedland (of Ivanhoe fame), and said the property compares to Platreef in South Africa, a huge PGE and base metals mine currently being developed in a joint venture between Ivanplats and Ivanhoe Mines.

Expected to commence production in 2022, at an initial 4 million tonnes per annum, the Platreef project targets the high-grade Flatreef deposit, which has an average vertical thickness of 24 meters, within a mineralized belt that forms the northern limb of South Africa’s Bushveld Igneous Complex – host to around three-quarters of the world’s platinum resources.

The underground mine, expected to produce 476,000 ounces of platinum, palladium, rhodium, and gold, 21 million pounds of nickel and 13Mlb of copper over an estimated mine life of 32 years, runs deep – mineralization occurs between 700m and 1.2 km below surface.

Dummett said he planned to visit Eagle Rock to confirm what he’d learned at the UBC conference dinner, but he needed to head to South Africa first. Sadly he never made it; Dummett died tragically in a car accident, and nothing more became of the property.

The story picks up about five year ago when consultants to Champion Bear were in Johannesburg (Joburg) meeting with geologist David Broughton – another huge name in mining, having overseen discovery of two major deposits, Kamoa in the DRC and Platreef in South Africa.

Champion Bear’s consultants again brought up Eagle Rock but Broughton said Ivanhoe had sunk too much money and was too involved in Platreef for the company to look at a Canadian acquisition. Again, the trail to a major ran cold.

Kantor then made a joint-venture deal with Implats out of South Africa, and Wallbridge Mining for Champion Bear’s Parkin property. Under the JV terms, Wallbridge could spend $2 million on exploration to earn 50% of the property, which overlies 7 km of an offset dyke, one of the last undeveloped dykes in Sudbury – no other junior can lay claim to owning so much of an off-set in Sudbury, expect to hear much more regarding this JV.

Wallbridge honored its expenditure commitments and gave Champion Bear 450,000 shares, meaning Champion Bear is carried (no exploration spending required) to production – the ore is expected to come from the footwalls – and Implats (now Sibanye-Stillwater) is required to split the proceeds of production 50-50 (plus interest) with Champion Bear.

That deal whetted Implat’s appetite for Eagle Rock, along with other major mining companies that began circling CBA’s now-flagship property. North American Palladium expressed interest in its PGMs, Chile’s Antofagasta wanted it for its copper.

It was around the same time that Tony Green, Falconbridge’s VP Exploration, decided to spend six months at Eagle Rock doing an evaluation. He was joined by a geologist from Antofagasta and North American Palladium, yet despite them recommending to management that a deal be made, misfortune once again fell on Eagle Rock.

North American Palladium went into receivership and was later rescued by a US$130 million loan from Brookfield Business Partners LP, a majority shareholder of Implats, which would buy NAP out for about a billion dollars.

Impala had wanted in as well, but they lost their ground at Parkin, and were later taken out by Lonmin of South Africa, the world’s third-largest PGE mining company.

Back to current operations at Eagle Rock, Kantor says previous exploration including this past winter’s drill program shows that an already large orebody, open in all directions, is clearly on the property, meaning Champion Bear is able to skip the discovery phase and jump right into resource expansion and delineation.

“We got real lucky but we always knew we’re not looking for the metal, we know it’s there. The vent comes in like a horseshoe, where all the solutions come up and spread on the ground, a layered-type intrusion. The sulfides are like a sponge and it sucks in the PGMs, Pd, Pt and Au,” Kantor explained.

From the 2011 Eagle Rock 43-101 Technical Report : “The sulphides are structurally controlled. The Campbell Zone trend extends for several kilometres from the Campbell Zone. It extends east, then south, and eventually west along the north shore of Entwine Lake. The trend mimics the circular shape of the west end of Entwine Lake Intrusion. CBA thinks the trend is related to the structural control of the sulphide mineralization.”

Sulfide tenors and recoveries at this stage look good. “The tenor of the metal is like a hard-packed gravelly sand,” Kantor says, “it breaks up nicely.”

A metallurgical study done back in 2001, using a moderate grinding of 80% passing 74 microns, followed by froth flotation appears straight forward for producing a copper concentrate that contains most of the by-products metals of value. Recoveries were between 90 and 95% copper, platinum and palladium. Gold and silver were recoverable at 85-90%. The resulting sulfide concentrate produces grades between 25 and 29% Cu, 5 to 14 g/t Pt, 8 to 15 g/t Pd, 6 to 9 g/t Au and 200 to 280 g/t Ag.

It may even be possible to produce rhodium (the most valuable PGE) although tests have not yet been carried out.

Along with palladium and platinum, included on the list of the Canada-US Joint Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration, Champion Bear also owns Separation Rapids – a lithium-tantalum pegmatite play. Located 55 km north of Kenora, ON, the property is within the eastern extension of the Cat Lake – Winnipeg River pegmatite field, that hosts the Tanco underground caesium/ tantalum mine in Manitoba.

Conclusion

We like PGEs because they support our electrification of the global transportation system thesis, and because the market is in no danger of oversupply – especially for palladium, which has run eight straight annual supply deficits and likely to see a ninth this year.

The leading palladium producers are saying there’s no way we’re looking at a glut anytime soon, for all the above-mentioned factors: labor disruptions at South African platinum mines, power outages, expansion problems due to constrained water supplies and processing capacity, not to mention the fact that PGE mining is difficult and expensive – it’s not easy to increase production even if prices rise considerably. And it takes five to seven years to open a new mine.

Palladium just topped $2,500 an ounce before backing off and platinum prices have turned around despite a rocky year for diesel autocatlyst demand – now regularly trading above $1,000/oz.

Their importance to America’s national security is underlined by the inclusion of PGEs in the US government’s list of 35 critical metals. This means the PGE sector will likely be the recipient of research and development, information-sharing and government funding to ensure that North American PGE production does not fall behind its competitors.

As platinum, palladium, copper, gold and silver prices continue to do well, exploration companies are realizing that this is a good place to be.

We have chosen Champion Bear Metals as one of our top picks for PGEs because it is one of only two reef-type PGE deposits in North America we’re aware of – the other being Stillwater. The scale of the Stillwater Complex in southern Montana and South Africa’s Platreef deposit emphasize that it’s this type of mineralization a PGE mine developer should be in.

Champion Bear has the good fortune to have held onto this very rare, very prospective Cu-PGE-PM reef like deposit that contains not only palladium, the darling metal in terms of price gains in each of the past two years, but platinum and copper – both of which are rising in value as “green” metals.

At AOTH we like the fact it’s copper/ PGE, not nickel/ PGE. Why? Well the Campbell Zone doesn’t have the same type of mineralization as the Platreef or J&M reefs, or even Sudbury (aka the BIG Nickel) – copper versus nickel – but just the fact that it’s an open-pittable reef-type deposit with grades many times that of British Columbia’s world class copper/ gold porphyries (just Eagle Rock’s copper grade is equal to the CuEq of the best of BC’s porphyries), with excellent metallurgy and all the necessary infrastructure in place speaks highly of the deposit.

There are a lot of major copper miners in the world, Chile’s Antofagasta wanted Eagle Rock for its copper, other companies, like North American Palladium expressed interest in its PGEs. I think having the copper opens CBA up the very real possibility of a much bigger mix of companies who might want to get involved with Champion Bear, or the holy grail, do a buy out.

We know for a fact that Eagle Rocks’ Campbell Zone is heavily mineralized; the question left to answer is; what is the extent of the deposit – in terms of strike length and depth.

The next two drill campaigns should unearth more clues as to what Champion Bear is drilling into. We look forward to seeing what they find.

Finally, the fact that Champion Bear was able to make a concentrate of 90-95% copper, platinum and palladium (+85-90% silver and gold) is another de-risking event – although metallurgical studies will certainly have to be updated. The tenors also do not appear to be an issue.

We haven’t said a lot about Champion Bear’s other three properties, the Parkin JV, Plomp Farm and Separation Rapids. For now, suffice to say they are all quality properties, with much more to come.

Champion Bear

TSX.V:CBA

Cdn$0.14, 2020.02.15

Shares Outstanding 52,393,326m

Market cap Cdn$7.33m

CBA website

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

aheadoftheherd.com

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Richard owns shares of Champion Bear (TSX.V:CBA), CBA is an advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.