Canadian military unprepared for war – Richard Mills

2023.01.11

“The world is getting more dangerous every day and we need to be ready for it,” General Wayne Eyre, Canada’s Chief of the Defence Staff told a House of Commons committee in October.

Canada’s top soldier was, of course, referring to the war in Ukraine, which has caused a re-think among NATO about the vulnerability of member countries, especially those bordering Russia.

There’s also the ongoing tensions between the Chinese and US navies over the South China Sea; a possible invasion of Taiwan, a United States ally that China considers a renegade Chinese province which must be re-united with the Motherland; an increasingly belligerent Iran, which has still not taken responsibility for shooting down a Ukrainian airliner three years ago, killing all 176 on board including 138 with ties to Canada; Taliban-controlled Afghanistan and its denial of basic human rights; and Arctic sovereignty in the era of disappearing polar ice — a matter of pressing concern to Canada, one of eight Arctic nations.

Gen. Eyre told the committee the West was “already at war with China and Russia” and that the two global powers were out to remake the world in their own image.

In a separate appearance before a different panel of MPs, Eyre warned that Canada’s hold on the Arctic is tenuous in the face of great power competition, something we at AOTH flagged three years ago. (more on the Arctic below)

The Canadian military has many brave, capable men and women serving under its command, but the lack of planning, underfunding, and under-procurement of necessary equipment/ weaponry, is leading to situations where Canadian soldiers are being sent into harm’s way ill-equipped. Here we highlight some of the areas of most concern.

Underfunded, underequipped, overstretched

In a year-end interview with CBC News, Gen. Eyre said the supply-chain disruptions and soaring food and energy prices, owing to rampant inflation triggered by hostilities between Russia and Ukraine, are likely just a taste of what’s to come. Author Murray Brewster, a veteran defence & security journalist, quotes NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, who warned in a Norwegian TV interview that there is a “real possibility” of the war in Ukraine escalating into a full-blown conflict between the western military alliance and Russia.

If that were to happen, Canada would be called upon to help its allies. The Canadian military is increasing its commitment to reassurance missions in Eastern Europe meant to keep Russia at bay (Canada last summer agreed to put more resources into the battlegroup it leads in Latvia to make it a brigade-sized force), but the military is also being asked by the Liberal government to be more active in the Indo-Pacific region, by deploying an additional frigate and undertaking security force training in countries like Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

Meanwhile, successive governments have piled more domestic responsibilities on the military, such as helping long-term care homes in Ontario and Quebec to deal with covid-19 outbreaks, and emergency response due to extreme weather events and forest fires.

Eyre said the military’s long list of responsibilities means it must be smart about how it deploys its resources: “There’s just not enough Canadian Forces to be able to do everything.”

Regarding procurement, the Ukraine war has forced the military to part with crucial equipment such as ammunition, howitzers and anti-tank weapons. Eyre told the CBC there are urgent procurement efforts underway to replace donated gear and cover those critical gaps.

Still, the country’s top soldier says military readiness is “one of the things that keeps me up at night.”

Speaking at a defence conference in Ottawa last March, Eyre said the Forces need to modernize in the face of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s recklessness. How to do that is what worries him. The pandemic pushed the institution “to the limits”, with covid-19 exhausting members and recruitment numbers down. The military therefore needs to speed up recruitment, modernize its equipment and boost training to ensure it can sustain its contribution to NATO.

Defense Minister Anita Anand has said the country has the capacity to send an additional 3,400 military members, even with a diminished force of about 65,000 regular members and 30,000 reservists, but the government has faced questions about whether it can sustain that level of deployment.

One has to wonder, though, if more had been done earlier, the military wouldn’t find itself in this kind of bind. In another article, the CBC’s Murray Brewster reports on how the military’s +decade-old plan to re-build went awry:

More than a decade ago, as Canada’s war in Afghanistan was grinding to its conclusion, a plan was drawn up to rebuild, refresh and re-equip the army for the future.

It withered and died over several years — a victim of changing defence fashions, budgets, inter-service and inter-departmental bureaucratic warfare and political indifference…

Several of the key weapons systems in the 2010 plan — ground-based air defence, modern anti-tank systems and long-range artillery — are among the items the Liberal government is now urgently trying to buy, just as other allied nations also scramble to arm themselves against a resurgent Russia.

In November, a senior defence planner told a conference that it could take up to 18 months to land some of the less complex items on Ottawa’s wish list. In the meantime, Canadian troops in Latvia staring across the border at a wounded, unpredictable Russian Army will have to make do — or rely on allies…

The military is looking for ground-based air defence systems to guard soldiers against attack helicopters, low-flying jets and missiles. It’s seeking anti-tank weapons like the U.S.-made Javelin, which the Ukrainians have used to deadly effect against the Russians. It’s trying to source better electronic warfare systems and weapons to counter bomb-dropping drones.

One of the most egregious examples of the military’s lack of preparedness that resulted in Canadian troops being sent into battle with a target on their backs, was in Afghanistan, where, as Brewster writes, the Canadian Army went into a desert war wearing green camouflage fatigues and in unarmoured vehicles.

Regarding politicians’ failed promises to beef up the military, Brewster quotes former army commander and lieutenant-general Andrew Leslie saying: “Liberals and Conservatives both have found a neat trick of telling Canadians that they are increasing defence spending, that the capabilities are on the horizon, but then somehow never getting around to fine-tuning the various procurement systems so that the money gets out the door.”

In other words? Typical government bureaucracy and politicians playing the blame game.

In the article, defense expert Dave Perry wonders why the equipment the Liberals are scrambling to buy now, i.e. the air-defence and anti-tank weapons they identified as important five years ago, hasn’t been purchased already.

Leslie, as Brewster states, has a more tough-minded view:

“I was the army commander for four years at the height of the Afghan war. So I had a front row seat to the various influencers, and their shenanigans concerning defence procurement,” he said.

“Tragically, it wasn’t until Canadians started dying in Afghanistan that a great deal of focus and energy was placed on defence procurement. And the bureaucracy was told in no uncertain terms — woe betide any of you who slowed down programs that caused more soldiers to die because they didn’t have the equipment they needed.”

The lackadaisical attitude extends to the military’s domestic procurement needs. An upgrade to the country’s search and rescue helicopter fleet was first proposed over five years ago, but the money didn’t arrive from Ottawa until last month. The $1.24 billion program to extend the Cormorants’ life was announced late on the last day before the Christmas holidays, presumably to hide from the media the fact that the initial budget for the life extension was $1.03 billion.

A longer-term view of the problem reveals how Canada’s military reputation as a formidable fighting force during the first and second world wars, has been diminished due to a lack of government funding.

Michael Godspeed, a former lieutenant-colonel in Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, writes in The Toronto Star:

Since the 1960s, Canada has been steadily chiselling away at its military, promising increased efficiencies with diminished spending. Now we find ourselves with a tiny, underequipped and demoralized force that has largely been reduced to providing token forces in symbolic roles. The army is forced to cannibalize and break up teams in understrength units to maintain half of a patchily equipped battle group in Latvia. The air force and navy, woefully short of aircraft, ships and trained crews, are forced to wait decades to replace obsolete and worn-out equipment with ever fewer numbers.

In fact, ignored by a succession of governments, Godspeed sees Canada’s military as no longer even able to maintain what he describes as “the bogus peacekeeping myth”:

The Armed Forces have now atrophied to the extent that we can no longer field and sustain a major unit for any kind of operation abroad.

The Arctic

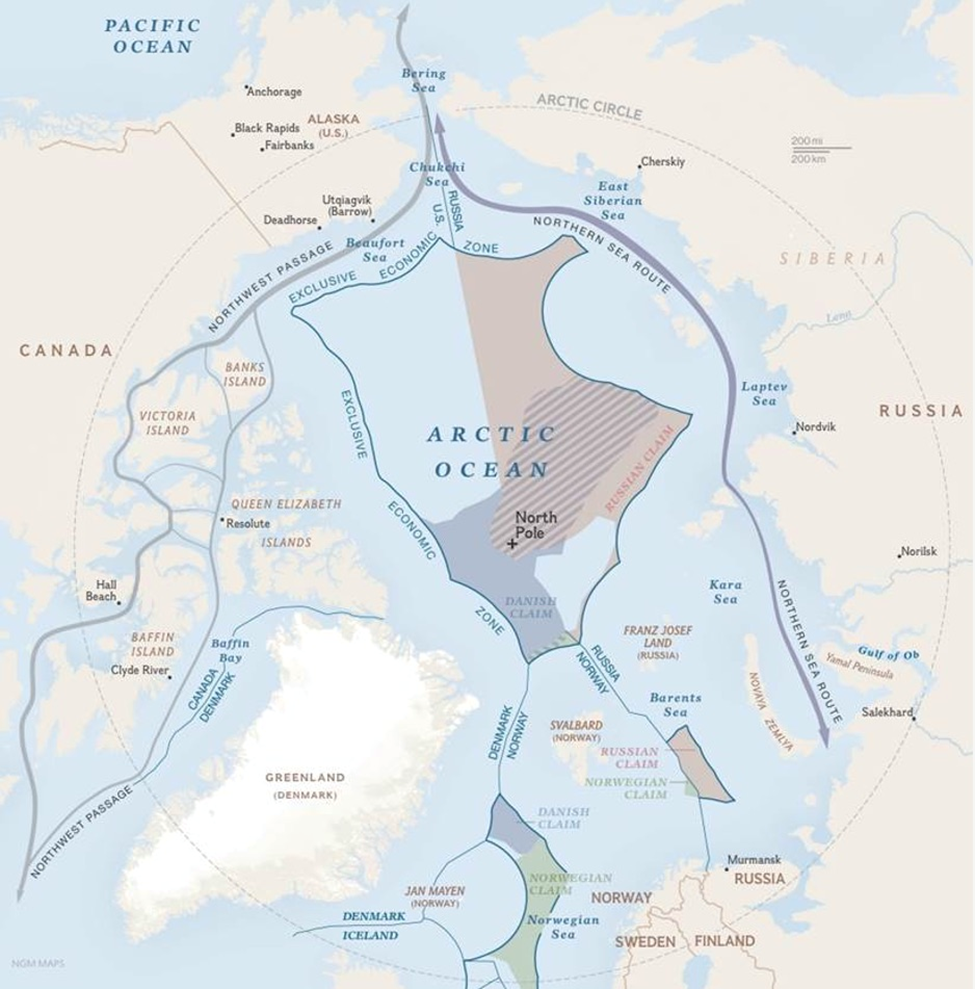

Who has jurisdiction over the North Pole, the Arctic Ocean, inland seas and land masses that we refer to as the Arctic? Control over all of this 20-million-square kilometer territory including “exclusive economic zones” (EEZs), is divided among the eight Arctic states: Canada, the United States, Russia, Norway, Denmark/Greenland, Iceland, Sweden and Finland.

EEZs are zones prescribed by the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Within these zones, a state has the right to explore and extract marine resources including hydrocarbons underneath the seabed, and energy produced from water and wind. EEZs stretch out 200 nautical miles from the coast. An Arctic nation, within the EEZ, has rights below the the ocean surface, but nobody owns the surface – they are known as international waters. The North Pole and the surrounding Arctic Ocean, for example, are not owned by any one country.

When the Arctic Ocean was covered with a thick sheet of ice, this arrangement worked reasonably well, with little conflict. But the disappearance of the ice has stirred the imaginations of polar nations intent on taking advantage of more accessible natural resources and shipping routes.

If current climate trends continue, scientists estimate that the Arctic Ocean will be ice-free by mid-century. To clarify, that means sometime between 2030 and 2050, in September, the month with the least amount of ice cover, the Arctic Ocean will be entirely uncovered by ice.

Russia was the first to claim Arctic ownership beyond its territory, in 2007. Russia has also reportedly been expanding infrastructure along its northern coast to exploit natural gas reserves.

Canada claims ownership of the Arctic Ocean archipelago. To asserts its claims, the country has created a new research center, is developing autonomous submarines, and conducting search and rescue exercises in anticipation of growing ship traffic in the Northwest Passage.

In 2019, a House of Commons committee urged the Canadian government to work with NATO to identify Russia’s military intentions in the north and to shore up Canadian Arctic sovereignty.

According to Global News, the recommendation came “one day after Russian President Vladimir Putin outlined an ambitious plan to increase Russia’s Arctic presence, including expanding its fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers and building new ports and other infrastructure.

The Russian leader invited foreign companies to invest in projects at both ends of the Arctic shipping route, from Murmansk in Russia’s northwest to the Kamchatka Peninsula in the east.

With Arctic sea ice melting, Putin said he plans to dramatically increase Russian cargo-ship traffic in northern shipping lanes.”

Also in 2019, Russian newspaper Izvestia reported that Russia’s military will resume fighter patrols in the North Pole for the first time in 30 years. CTV News states:

Recent Russian moves in the Arctic have renewed debate over that country’s intentions and Canada’s own status at the top of the world.

The newspaper Izvestia reported late last month that Russia’s military will resume fighter patrols to the North Pole for the first time in 30 years. The patrols will be in addition to regular bomber flights up to the edge of U.S. and Canadian airspace.

Russia has been beefing up both its civilian and military capabilities in its north for a decade.

Old Cold-War-era air bases have been rejuvenated. Foreign policy observers have counted four new Arctic brigade combat teams, 14 new operational airfields, 16 deepwater ports and 40 icebreakers with an additional 11 in development.

Bomber patrols have been steady. NORAD has reported up to 20 sightings and 19 intercepts a year.

To be fair, Canada and the US operate bases in the Northwest Territories and Alaska capable of dispatching troops, aircraft and submarines. NATO countries regularly train for cold-weather conflict including a massive training exercise in 2018v in Norway called Trident Juncture. The two weeks of war games involving 50,000 troops from 31 nations, was the largest training exercise since 1989.

However, compared to Russia, and for that matter, China, not even a polar nation, Canada’s Arctic efforts pale. The government has no official Arctic policy and there is an extensive list of unfulfilled infrastructure promises including no high-speed internet. The only significant project has been a paved road completed to the Arctic coast at Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories.

Lately China has become more interested in the Arctic, eyeing less ice cover as an opportunity to expand its ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI).

The ‘Polar Silk Road’ is an extension of its ambitious plans for a series of BRI infrastructure spends designed to create a trading orbit in southern Asia. The Polar Silk Road includes a potential shipping route across the Pacific and the development of energy and mining resources in the region, plus fishing and tourism.

The country is hoping to diversify its energy resources away from the Persian Gulf and Africa, by investing in Russia’s Yamal LNG complex and in Norway’s oil and gas fields. Between 2012 and 2017 China spent around $90 billion on Arctic infrastructure and natural resource extraction.

In 2013 China was granted observer status on the Arctic Council.

A recent article in The Hill explains in detail the reasoning behind China and Russia’s greater involvement in the world’s northern-most reaches:

The Chinese need to sustain economic growth. One way to do that is to improve their access to natural resources, particularly energy, rare-earth minerals and sea-based protein. They also would like to develop an alternative shipping route from Europe to Asia that is not dependent on the Straits of Malacca or the Suez Canal, areas with a heavy U.S. naval presence.

Chinese actions in the Arctic are consistent with these goals. They are investing heavily in Russia’s natural gas fields in the Yamal Peninsula, mining in Greenland, and real estate, alternative energy and fisheries in Iceland. They are building icebreakers and ice-hardened ships to ply Arctic waters. And they are asserting themselves into international debates over Arctic governance, most recently by calling themselves a “near-Arctic” state.

Russia’s status as a great power is largely contingent on what they do in the Arctic. Their economy is heavily dependent on exporting oil and gas, much of which comes from their Arctic territory. Their fleet of nuclear-armed submarines is based in Murmansk, above the Arctic Circle. And they see the Northern Sea Route (NSR), a shipping channel along the Siberian coast, as a potential revenue source as well as an area that needs to be protected from oil spills and controlled from a military security perspective.

Russian actions in the Arctic arguably are consistent with these interests. They developed the Yamal natural gas fields with Chinese assistance. They refurbished or created military bases near Murmansk and along the NSR, and deployed what they claim are defensive weapons and search and rescue capabilities to those bases.

The combined Arctic moves of Russia and China have raised alarm bells in Washington, which fears its old Cold War enemies are planning to exercise territorial ambitions in the far north. National Geographic notes that in 2016, China tried to buy an abandoned naval base in Greenland, sailed its first ice breaker through the Northwest Passage in 2017, and in 2018, published a white paper outlining its Arctic plans.

Former US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned his fellow foreign ministers at a meeting of the Arctic Council – an inter-governmental discussion forum – that the Arctic is emerging as a new “Great Game” between the US, Russia and China (notice Canada is not included), or maybe even a renewed Cold War.

Canadian politicians are also concerned about the new northern power grab. CBC reported on a Liberal MP saying that Canada will have to “use it or lose it” if it wants to fend off challenges from Russia in the Arctic.

As Russia, China, and increasingly, the US flex their Arctic muscles, Canada is the 90-pound weakling in the gym – having instituted a five-year ban on offshore energy exploration that was recently extended.

Back to General Wayne Eyre, the defence chief says one of his main concerns is protecting Canada’s Far North. The reason is an increasingly hostile Russia. “Take a look at what Russia has done. They have re-occupied formerly abandoned Cold War bases,” Eyre said in the above-mentioned CBC story. He notes Russia also has instituted its own defence strategy to prevent adversaries from occupying its northern territory by land, sea or air — a strategy based on what China has done in the South China Sea.

Much was made last year over a four-year, $4.9 billion plan to modernize NORAD — the North American air defense system. The intent is to create a layered defence over the Far North that will guard a against not only strategic bombers, but also ballistic, cruise and hypersonic missiles. However, the recent skinny on the plan is it has a long way to go and a number of technical obstacles to overcome.

The most immediate problem is the country’s aging RADARSAT Constellation satellites, whose lifespans are due to expire in 2026. According to a Jan. 4 article by the CBC’s Murray Brewster, replacements for those satellites, which are used by several government departments including National Defense, are still on the drawing board. Military surveillance satellites promised by the Liberals in 2017 aren’t set for launch until 2035.

Another issue concerns what are known as “over the horizon” (OTH) radar systems that can locate targets beyond the range of conventional radar. The systems draw a lot of energy and scientists are trying to figure out how to power them in remote northern locations.

As for whether the Defense Department can stick to the $4.9B budget for upgrading NORAD, a recent development suggests probably not. The price tag for acquiring six Arctic Offshore Patrol Ships, and two additional similar vessels for the Coast Guard, has reportedly soared to $6.5 billion. The earlier projection for the patrol ships was $4.3 billion; the Coast Guard vessels are $100 million over budget.

According to the CBC, Both procurement services and the Department of National Defence blame the increases on the labour shortages and supply chain issues brought on by the pandemic.

The F-35 saga

When it comes to military procurement snafus, though, everything pales in comparison to what happened when Ottawa set out to replace the Royal Canadian Air Force’s aging CF-18 fighter jets.

In 2010 the Conservative government under Prime Minister Stephen Harper signaled its intent to sole-source 65 F-35s, made by US defense contractor Lockheed Martin. The plane has the most advanced sensor suite of any fighter in history, including the Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radar, Distributed Aperture System (DAS), Electro Optical Targeting System (EOTS) and advanced electronic warfare capabilities to locate/track enemy forces, jam radars and disrupt attacks.

However, the F-35 was, and is, expensive. At US$35,000 per hour of flying time, the planes were thought to be too expensive to maintain over the long term. That, along with reports from both the auditor general and the Parliamentary Budget Office, which questioned the cost and the federal government’s lack of due diligence in getting competing quotes, led to the procurement plan being shelved.

When the Liberals were elected in 2015, they promised not to pursue the F-35, instead vowing to buy a cheaper airplane and plow the savings into the navy. But the Trudeau government eventually relented and allowed Lockheed Martin back into the contest for new aircraft.

They later planned to sole-source 18 Super Hornets built by Boeing as an interim measure, but canceled the plan after Boeing launched a trade dispute with Montreal-based aerospace firm Bombardier.

In the meantime, CBC said, the government was forced to invest hundreds of millions of extra dollars into the CF-18 fleet to keep it flying until a replacement could be delivered.

In the summer of 2020, three bids were offered in a $19-billion competition. They included Lockheed Martin Canada’s F-35, Boeing’s Super Hornet, and Saab with the latest version of its Gripmen jet.

In an op-ed, the CBC’s Murray Brewster says the decision facing the government, on whether to go with the American F-35 or the Swedish Gripmen, was more than a choice between two expensive aircraft; it’s also expected to say a lot about how the federal government sees Canada’s place in the world — whether it remains tied to a politically shaky United States or to a Europe that is determined to step out of Washington’s defence shadow.

For decades, RCAF pilots have flown American-made planes, the notable exception being during the 1940s, when the Air Force used the British-made Spitfire. The last European-designed warplane flown by Canada was the British de Havilland Vampire, a jet fighter that was retired in the late 1950s, says Brewster.

Fast forward to December, 2022, when after months of negotiations with the US government and Lockheed Martin, DND was approved to spend $7 billion on 16 F-35s. Canada will apparently purchase the rest of the 88 jets in blocks over the next few years, with the goal of replacing the now-40-year-old CF-18s between 2026 and 2032.

The sign-off on the final contract to buy the F-35s happened this week. However the never-ending delays on this program continue, with the first planes not expected to be delivered until 2026, and the first F-35 squadrons not operational until 2029 — 19 years after they were first proposed.

Conclusion

The fact that it took so long to finalize a plan to upgrade Canada’s war-planes says a lot about where the federal government’s priorities lie. At least the Conservative government put a plan in motion. The Trudeau Liberals seem more concerned about rooting out sexual harassment and promoting gay rights in the military, than improving Canada’s war-fighting capabilities and maintaining its military strength at home.

Splashy announcements of military expenditures, on items like fighter planes and search & rescue helicopters, make for good campaign promises, especially in courting the right of center vote, but governments on both ends of the political spectrum are guilty of dithering, and not following through with the money.

A 2010 plan to rebuild the army was left hanging, and now, several of the key weapons systems — ground-based air defence, modern anti-tank systems and long-range artillery — are among the items the Liberal government is now urgently trying to buy, just as other allied nations also scramble to arm themselves against a resurgent Russia.

As I was editing this article for publication this morning this following link was sent to me, and it’s a must read.

Canada buys Ukraine $400M air-defence system; Canadian Army still waits for such equipment

The Liberal government is spending more than $400 million to buy air-defence systems for Ukraine even though the Canadian Forces has been without such equipment for more than a decade. Anand did not explain how the government was able to act so quickly in acquiring the air-defence system for Ukraine while a similar project for Canada’s military continued to go unfulfilled.

Unbelievable. I have zero problem supporting Ukraine…after our own troops are properly outfitted.

In the Arctic, the rapid melting of polar sea ice has made the once ice-jammed Northwest Passage navigable, creating a major defensive vulnerability; the shortest route for Russia to invade North America is now through the north pole.

Russia was the first to claim Arctic ownership beyond its territory, in 2007. The country has increased Arctic presence includes expanding its fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers and building new ports and other infrastructure. Lately China has become more interested in the Arctic, eyeing less ice cover as an opportunity to expand its ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI).

Compared to Russia, and for that matter, China, not even a polar nation, Canada’s Arctic efforts pale. The government has no official Arctic policy and there is an extensive list of unfulfilled infrastructure promises including no high-speed internet. The only significant project has been a paved road completed to the Arctic coast at Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories.

Apart from Canada being asleep at the switch in the Arctic, and the government’s lack of urgency when it comes to procuring new military equipment, I think the strongest criticism should be directed at decisions that put our military men and women at risk. Sending soldiers into battle against the Taliban dressed in green camouflage is one example, another is a drug prescribed by the Canadian Forces to fight malaria.

The anti-malarial drug mefloquine, or Lariam, was withdrawn from use by the US military because of concerns about dangerous side effects, that can range from anxiety, vivid nightmares and depression, to hallucinations and psychotic episodes.

But Canadian troops serving in malaria-prone regions continued to be prescribed it, into the 2000s, after which it was finally halted as a first-line defense against the mosquito-borne illness.

In 2019 CTV News reported that eight Canadian veterans are suing the government, claiming they were poisoned by a military-issued anti-malarial drug while on missions in Somalia, Rwanda and Afghanistan. Seeking more than $10 million each, the veterans say their lives have been destroyed by the drug Mefloquine.

Lawyer Paul Miller is representing the former soldiers and says his clients were forced to take the drug and are still living with the side effects, including psychosis, rage, paranoia, insomnia and tinnitus.

“The soldiers had no choice in taking the medication. They were under fear of court martial and imprisonment if they didn’t take it. There was fraudulent concealment of the side effects and they were never told that if you suffer certain side effects you need to discontinue the medication,” Miller said.

Forcing soldiers to take a harmful drug while sending them into harms way while totally under equipped and unprotected must rank among the most odious things any modern developed nations military has done to its men and women in uniform. And now showing Ukraine has priority over Canada’s own really does highlight how our politicians see our military.

Surely we can do better. It starts with a recognition, by government, that the health and training of Canadian Armed Forces personnel is among the nation’s highest priorities, along with providing them with the best equipment available for both territorial defense and projecting force overseas.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.