Canadian megaprojects are back on the table, but who will pay for them? – Richard Mills

2025.03.15

“Maybe the one good thing about Trump is the slap in the face we need to build pipelines and build mines in this country,” Ted McGurk, head of investment banking at TD Securities in Vancouver, said Tuesday during a panel discussion at the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada annual conference in Toronto. “We’re a resource country, and government needs to get out of the miners’ way. They are the biggest impediment to the industry, and they need to realize that.” — ‘PDAC: Trade war could fast-track mine approvals, panelists say’

The Trump tariffs against Canada have sparked a national conversation over not only digging up minerals, but diversifying our trade patterns from north-south to east-west and beyond, to markets overseas. While some have spoken of the need to reduce interprovincial trade barriers, others are fixated on building new infrastructure in the Arctic, reviving old ideas like oil pipelines from Alberta to the East Coast, or pushing ahead with megaprojects like the Grand Canal water diversion.

Here we summarize the main national, not regional, infrastructure projects being proposed, along with some of the challenges they face. Think megaprojects on the scale of the Canadian Pacific Railway or the Trans-Canada Highway, that admittedly would cost hundreds of billions of dollars, take several years to build, and likely encounter loads of opposition throughout the entire process.

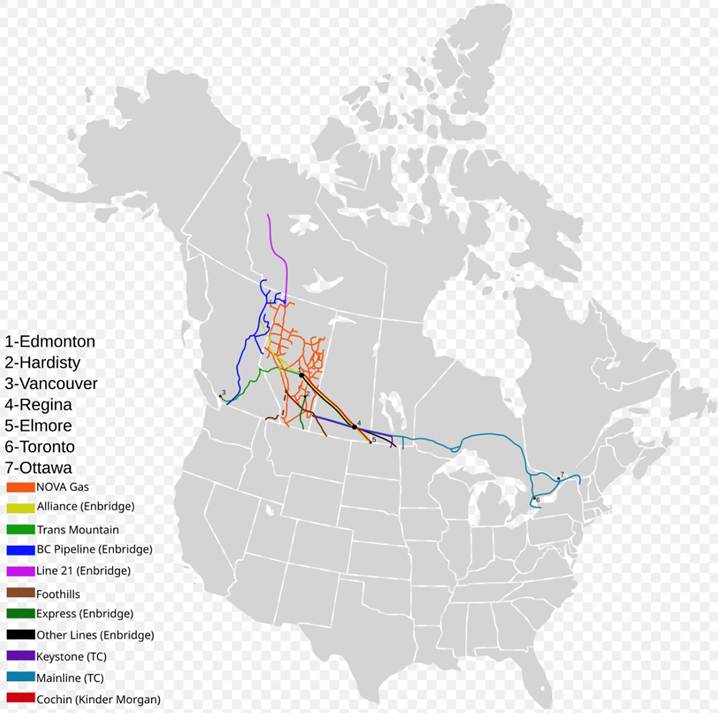

Oil & natural gas pipelines

Wikipedia lists 19 oil and natural gas pipelines currently operating in Canada. Seven are owned or partially owned by Enbridge, TC Energy owns or partially owns six. Other owners include Emera, ExxonMobil, ONEOK Partners, Williams Companies, and Montreal Pipeline Ltd. Trans Mountain Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Canada Development Investment Corporation, owns the Trans Mountain Pipeline that was taken over by the Canadian government in 2018 from Kinder Morgan for CAD$4.7 billion. The controversial and expensive twinning project was completed in May 2024 for $34 billion.

There are only two new pipelines that have been applied for: the Eagle Spirit pipeline (35 First Nations groups) that would run from Northern Alberta to Prince George, BC; and Enbridge’s Line 3, that would go from Hardisty, AB to Superior, Wisconsin.

Three pipelines have been rejected and two were abandoned. The rejected ones are TC Energy/ExxonMobil’s Alaska gas pipeline; Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline; and TC Energy’s Energy East pipeline, which would have run from Hardisty to Saint John, New Brunswick. TC Energy’s Keystone XL was abandoned, as was the Mackenzie Valley pipeline owned by Imperial Oil, The Aboriginal Pipeline Group, ConocoPhillips, Shell Canada and ExxonMobil.

On March 8 the National Post published a lengthy article titled ‘Why now is the time to build new oil pipelines: ‘We’ve got to get our act together‘

The crux of the piece is the question: How do we preserve national prosperity while shifting away from the United States — the largest buyer of Canadian oil?

Indeed most oil and gas pipeline run north-south not east-west. Efforts to build coastal pipelines, i.e., Energy East and Northern Gateway, have been scuppered by various issues including provincial (Quebec) and indigenous resistance and a lengthy regulatory regime.

Two bills passed by the federal government have made building new pipelines extremely difficult. The Impact Assessment Act introduced in 2018 by the Liberals was dubbed the “no more pipeline act” by former Alberta Premier Jason Kenney.

Bill C-48 brought into law a ban on oil tanker traffic off the northeastern coast of British Columbia.

Despite these hurdles, the possibility of building new pipeline infrastructure has taken on fresh urgency in the weeks since Trump grabbed the reins of power in mid-January.

As reported by the National Post, Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston has called for the proposed Energy East pipeline to the East Coast to be revived. Alberta Premier Danielle Smith, who laid out Alberta’s response to the Trump tariffs on March 5, suggested multiple potential routes for a new pipeline, including a revived Energy East that would bypass Montreal. She also suggested restarting the process to build Northern Gateway.

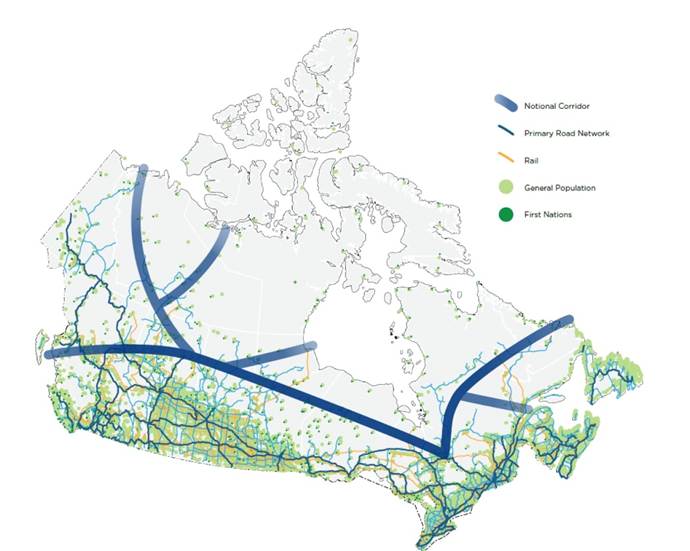

Another idea that has been recently aired is an east-west “energy corridor”. The idea isn’t new. It was once central to former Conservative leader Andrew Scheer’s 2019 election campaign.

Pierre Poilievre has been making the case for such a right-of-way since before he became the Conservative leader.

On the other side of the aisle, Liberal leadership candidate Frank Baylis proposed to build two pipelines as “corridors” to transport Alberta’s natural gas to Europe and Asia. The federal transport minister called the proposed $100 billion Northern Corridor “an appealing concept.”

The route would run through Canada’s north and would interconnect with the country’s existing transportation network. The idea would be to increase the nation’s capacity to transport resources to tidewater and access to global markets.

As reported by the CBC, The broader concept of an infrastructure corridor has been around since the 1970s… The core idea was to set aside space for highways, rail lines, power transmission and pipelines — basically any infrastructure Canada might need to tie the country together.

While a weaker price of oil and the spread between lower-quality, lower-priced Western Canadian Select oilsands crude and the WTI benchmark makes building pipelines all the more important, a glaring problem is the lack of industry interest.

For interest to be rekindled, the National Post agrees with me that there would have to be significant changes to the Canadian regulatory regime and commitments from government that the projects are guaranteed.

Also, the lessons from Kinder Morgan pulling out of Trans Mountain shows that for any coast-to-coast pipeline to be successful, the federal government would need to pony up the cash.

Sonya Savage, Alberta’s former energy minister, said that building a new pipeline crossing multiple jurisdictions is going to take a “whole of country effort”. Indigenous involvement would have to remain at the center of the process if there’s any hope of projects being built.

Recent polling suggests that Canadians are getting behind the idea of pipelines as a both an expression of patriotism and the economic reality of moving product from province to province instead of to the US.

An Angus Reid poll from early last month showed that 63 per cent of Canadians believe if more pipeline infrastructure for oil and gas were built it would strengthen the Canadian economy. (National Post)

But not so fast. There are voices calling for caution in rushing to build pipeline infrastructure when the economics don’t really make sense and there are better ways to spend taxpayer money on energy.

The Globe and Mail recently quoted federal Energy and Natural Resources Minister Jonathan Wilkinson saying, “People are getting way too ahead of themselves on the oil conversation. Everybody’s sort of running around saying, ‘Oh my God, we need a new pipeline, we need a new pipeline.’ The question is, well, why do we need a new pipeline?”

Columnist Adam Radwanski opines that there is no indication of serious private-sector interest in this scale of new oil infrastructure. Former Energy East proponent TC Energy is no longer in the pipeline business and nobody else has stepped up to advance a project that would cost tens of billions.

“That suggests enormous subsidies would be required to attract the capital, if not outright government ownership,” he writes.

A CBC story agrees that a revival of Energy East is unlikely due to unfavorable economics and high political and regulatory risk.

Meanwhile there are other pressing priorities including extracting critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite. The federal Liberals’ 2022 critical minerals strategy includes $700 million in public spending, and progress is being made, such as a proposed lithium refinery in Thunder Bay, Ontario.

Also, according to Radwanski, Leveraging already domestic development of new nuclear reactors could serve both our own energy-security needs and those of increasingly anxious overseas allies.

The Arctic

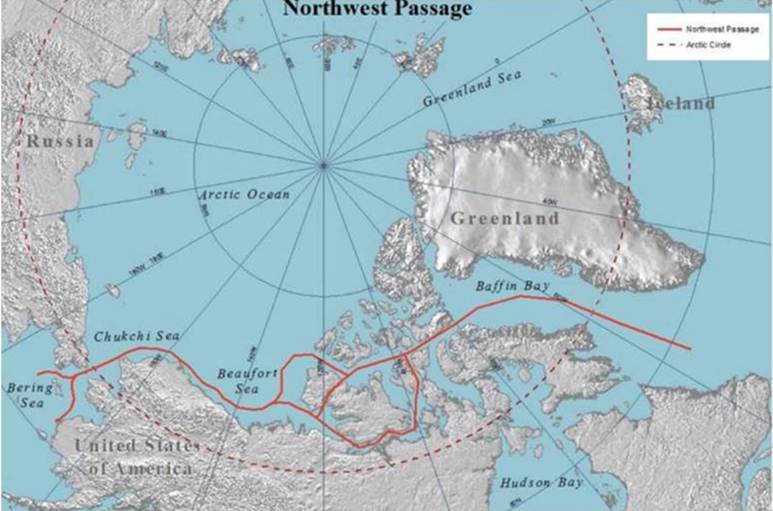

Canada claims ownership of the Arctic Ocean archipelago. To asserts its claims, the country has created a new research center, is developing autonomous submarines, and conducting search and rescue exercises in anticipation of growing ship traffic in the Northwest Passage.

The Arctic: The next ‘Great Game’ — Richard Mills

But countries’ investment in the Arctic is rather un-even. Despite having the second largest amount of land mass within the Arctic Circle, behind Russia, Canada has spent very little, as has the United States with only the northern third of Alaska considered to be Arctic.

The big spenders are Russia and Norway. National Geographic notes that Russia has “greatly expanded its military forces in the Arctic, becoming, by most measures, the dominant cold-weather player.” Russia’s northern fleet is the largest in the world at 60 ice breakers and another 10 under construction. Norway has expanded its ice-capable fleet to 11 ships. Both countries have invested heavily in oil and gas development.

To be fair, Canada and the US operate bases in the Northwest Territories and Alaska capable of dispatching troops, aircraft and submarines. NATO countries regularly train for cold-weather conflict.

However, compared to Russia, and for that matter, China, not even a polar nation, Canada’s Arctic efforts pale. There is an extensive list of unfulfilled infrastructure promises including no high-speed Internet. The only significant project has been a paved road completed to the Arctic coast at Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories.

But wait. Could the Canadian government actually be getting serious about Arctic infrastructure and Arctic defense? In April 2024 the Feds announced more money was being allocated to the North.

CBC reported the new defense policy, called ‘Our North, Strong and Free’, will include $8.1 billion over five years and $73 billion over 20 years in military spending:

The policy… is heavily focused on Canada’s North and Arctic sovereignty and includes money for new fighter jets, new maritime patrol aircraft and Arctic and offshore patrol vessels.

It also includes $1.4 billion over 20 years to buy specialized maritime sensors to conduct ocean surveillance on all three coasts.

In terms of new infrastructure in the Arctic, the policy includes $218 million to be spent over 20 years on what the federal government calls “northern operational support hubs.”

Federal Northern Affairs Minister Daniel Vandal said the hubs, which will include logistics facilities and equipment, will allow the Canadian Armed Forces to establish a year-round presence in the Arctic.

He also said the new policy commits to buying all-terrain vehicles and it will also renew and expand submarine fleets and create ground-based air defense systems.

Then in December 2024, Minister of Foreign Affairs Mélanie Joly announced the launch of Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy (AFP). According to the news release, the AFP is composed of four foreign policy pillars: asserting Canada’s sovereignty; advancing Canada’s interests through pragmatic diplomacy; leadership on Arctic governance and multilateral challenges; and adopting a more inclusive approach to Arctic diplomacy.

On Feb. 20, according to a government press release:

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, the Minister of National Defence, Bill Blair, Canada’s Ambassador to the United States, Kirsten Hillman, and Canada’s Fentanyl Czar, Kevin Brosseau, met virtually with Canada’s premiers to discuss Canada-U.S. relations and Arctic security.

Our North, Strong and Free, the $73 billion defence policy update the federal government launched in 2024 includes major investments in the North, such as airborne early warning and control aircraft, specialized maritime sensors, new tactical helicopters, a new satellite ground station in the Arctic, and northern operational support hubs, in addition to a separate $38.6 billion investment in NORAD modernization.

The latest federal government news on the Arctic arrived on March 6, with Minister of National Defence Bill Blair announcing Iqaluit, Inuvik, and Yellowknife as northern operational support hub locations.

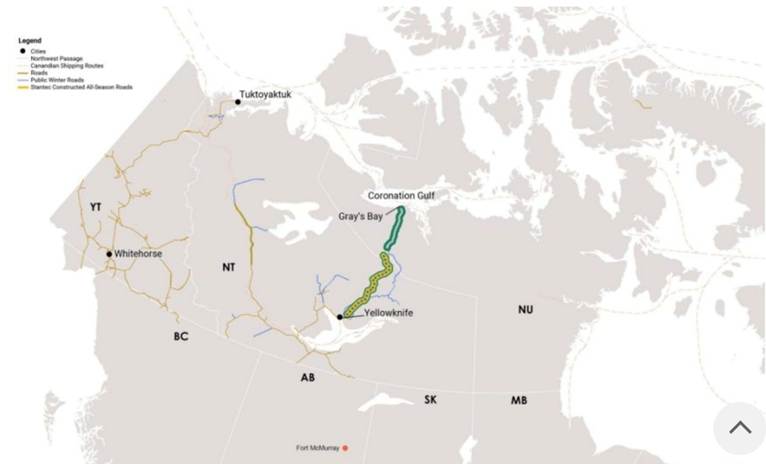

Northern premiers argue there are other areas where infrastructure investment can be tied to defence spending. Among the more ambitious pitches made by Northwest Territories’ Premier R.J. Simpson is to build road infrastructure to help mine and move the territory’s critical minerals.

For Nunavut, part of its ambition is deep-sea port facilities. These would bolster the territory’s fishery economy and help with the off-loading of goods and materials in summer seasons. It could also provide a naval presence along the Northwest Passage.

Canada does have plans for a naval facility at Nanisivik, which will serve as a refuelling station for Canadian government vessels in the Arctic, though it is a trimmed-down version of what was originally conceived. (CBC News)

As for new civilian Arctic infrastructure, Stantec, a consultancy, notes the lack of basic infrastructure in Nunavut for example, like railroads and all-weather roads, means materials must be shipped by sea or air. Two road projects currently underway are the Kivalliq Inter-Community Road (KICR) and the Grays Bay Road and Port (GBRP) project:

The GBRP route is a 230-kilometre all-season road and deep seaport. It will link Nunavut to Canada’s mainland via the Northwest Territories. The first phase of the GBRP vital corridor will connect a deep-water port in the center of the Northwest Passage to Contwoyto Lake—the northern end of the Tibbit to Contwoyto winter road. Future phases will provide year-round road access from southern Canada to the Coronation Gulf. Pending a positive decision on the environmental assessment, the plans call for a start of construction of the Grays Bay Road and Port in 2030; full operations are set to begin in 2035.

The July 2024 article notes the firm led the Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk Highway, which connects Canada from coast to coast, and has been involved in key Canadian Arctic projects like the Iqaluit International Airport and the Dempster Fibre Line.

According to The Conversation, the takeaway from a recent opinion poll found that Canadians are highly supportive of Arctic infrastructure. They perceive it as strategic and part of nation-building, with 42% considering it to be of national importance. The poll conducted by the Observatory on Politics and Security in the Arctic surveyed more than 2,000 Canadians last July-August.

James Bay/ Grand Canal Project

Donald Trump is not only after our energy, critical minerals and sovereignty, but now our water to boot.

When Trump was the Republican presidential nominee, he announced an idea to help alleviate California water shortages involving British Columbia.

Trump water faucet comments and the Columbia River Treaty — Richard Mills

“So you have millions of gallons of water pouring down from the north with the snow caps in Canada and all pouring down and they have essentially a very large faucet,” Trump said.

“And you turn the faucet and it takes one day to turn it. It’s massive. It’s as big as the wall of that building right there behind you. You turn that, and all of that water aimlessly goes into the Pacific (Ocean), and if you turned that back, all of that water would come right down here and into Los Angeles,” he said.

The faucet Trump is talking about is the Columbia River, which begins in southeastern British Columbia and flows south to Oregon, where it empties into the Pacific Ocean near Astoria.

Water — the next US-Canada trade irritant — Richard Mills

The Columbia River Treaty regulates how much water is flowing across the border and what it’s going to be used for. The treaty originally required Canada to provide 15.5 million acre-feet of water storage by building three dams: Duncan, Hugh Keenleyside and Mica.

First signed in 1961 by Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker and US President Dwight Eisenhower, the treaty was recently renegotiated and there is nothing in it about diverting limited water in US states like Idaho to California. Read more on the history

An agreement-in-principle signed in July enabled officials to update the treaty to ensure continued flood-risk management and co-operation on hydro power on the river, CTV News reported.

However, the latest news is that agreement has been paused.

The Guardian reported on Wednesday that the United States has paused negotiations while officials “conduct a broad review” of the Columbia River Treaty.

The final details of the treaty remain unfinished, with only a three-year interim agreement in place. While the future of the pact looks uncertain, either nation must give a 10-year notice before abandoning the deal, according to The Guardian.

In fact, Canadians may be surprised to learn that plans have been on the books since the 1950s to divert a large amount of water from Canada, state-side.

The North American Water and Power Alliance (NAWAPA) proposed to use nuclear explosions to blast canals and channel water from the north-flowing Yukon, Liard, and Peace rivers, southward to water-deprived US agricultural regions and cities. A 2015 column posted on Radio Canada International notes that NAWAPA is still very much alive, with detailed proposals and analysis made in 2010 and 2012.

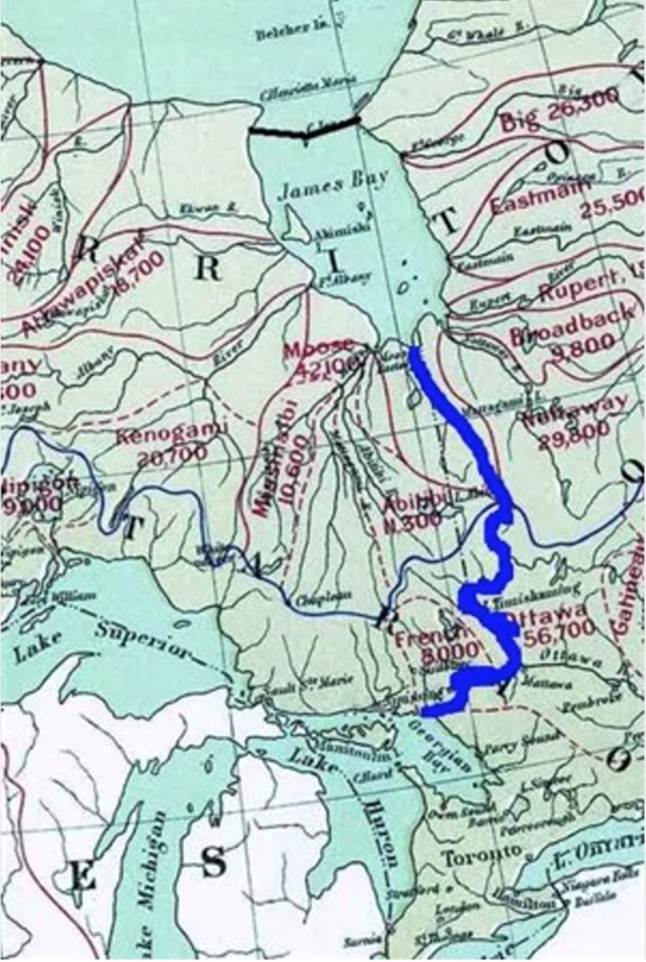

Another scheme, called the Grand Canal, would dam the top of James Bay, turning it into a huge reservoir, and cut a massive trench through northern Ontario that would bring fresh water to the Great Lakes, from where Americans could siphon however much water they need for farms, towns and cities impacted by climate change.

How feasible are the NAWAPA and the Grand Canal now that relations between Canada and the United States are at their lowest point in decades? One idea is to carve the trench and let the water flow into the Great Lakes without selling it to the Americans.

In this way it could be conceived as a megaproject on the same level as the James Bay Project, described in one video as “North America’s Three Gorges Dam”:

Composed of eight separate generating stations, numerous dams and reservoirs, the James Bay Project measures roughly 350,000 square kilometers and cost upwards of $20 billion to complete. It officially got underway in 1971 and was halted in 1994 amid environmental and social concerns including high levels of mercury in the water.

The megaproject took roughly 14 years to complete and included large-scale diversions of three rivers to the newly dammed reservoirs on the La Grande River, which nearly doubled the flow of the rivers from 1,700 cubic meters per second to 3,300. Three power stations were constructed during this phase, known as Robert Bourassa La Grande 3 and La Grande 4.

LG2 was built between 1972 and 1981 and remains the largest power generating site in North America, with an installed capacity of 5,616 megawatts and as the generating station is also underground, 137.2 meters to be exact, it is also the largest underground power station on the planet. The dam itself is located 6 kilometers upstream from the generating station and measures 162 meters in height and has a huge length of 2.8 kilometers. Phase one was rounded out with the construction of the LG3 and LG4 dams along with five reservoirs which amounted to a colossal area of 11,300 square kilometers which is around the size of Wales.

A total of 250 dikes and smaller dams were constructed in the area with one dike in particular reaching an extraordinary 56 storeys. A vast network of transmission lines measuring 4,800 kilometers was installed to bring power to southern Quebec and also evidentially to connect to the US power grid. Phase 1 was officially completed in 1984.

The second phase of this staggering project got underway in 1989 and included the construction of five secondary power plants — La Grande 1, La Grande 2A, La Forge 1, La Forge 2 and Brisay, which added a further 5,200 megawatts of generating capacity. Phase 2 also included three new reservoirs amounting to a further 1,288 square kilometers which is bigger than the city of Los Angeles.

The project now produces 83 terawatt hours a year which is enough to power the entire country of Belgium.

While the James Bay Project had its controversies —inter-union conflicts, riots, grievances by the Cree and Inuit over lack of consultation, and even the involvement of the Canadian mafia— there is no doubt that it brought about feelings of pride.

One commentator on ‘The James Bay Project: Three Gorges Dam of the West’ by Megaprojects YouTube channel states:

“As a Quebecer I want to nuance the negative effects of these projects. James Bay, along with other hydro-electric projects that were completed lately, are usually a great source of pride. They rallied a majority of the Quebecers behind a single project in which we were world leaders. The La Grande 2 power plant was for a long time the largest of its kind in the world. The power line that brings the electricity down south were the first in the world to be 735,000-volt. All these dams, while not perfect, have been producing electricity for very cheap (4-5 cents per KWh — our electricity is much cheaper than our neighbors) for many years, displacing coal and diesel and other more polluting power generation methods. Quebec is still today a major player and leader in this domain and has been implicated in many hydroelectric projects around the world.”

Conclusion

Megaprojects on the scale of the James Bay Project, the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Trans Canada Highway are great sources of pride for Canadians but they cost a bundle. We are talking a hundred billion dollars just to dig an interprovincial “energy corridor” — essentially an empty trench to be filled with future utilities.

Nobody likes to see the cost of these massive projects balloon far beyond their initial estimates, but that is inevitably what happens when governments take them on. The alternative is to have the private sector build them but we saw what happened with Kinder Morgan and Trans Mountain. My opinion is they can’t be built without major government backing — including funding and an easing of regulations.

The public mood would also have to shift from anti-pipeline, anti-development, to one that embraces pipelines, water diversion projects, and Arctic infrastructure building as sources of national pride.

It’s a big ask, but one whose time may have come, thanks to a US President that no longer respects his northern neighbor.

The last word goes to Jason Kenney, the former premier of Alberta, who recently told CBC’s ‘West of Centre’, “Maybe this is our wake-up call … this is the end of our holiday from history. It’s time for us, as a country, to put on our big-boy pants. It’s time for us to stop talking about things like productivity and competitiveness and actually damn well do it.”

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Share Your Insights and Join the Conversation!

When participating in the comments section, please be considerate and respectful to others. Share your insights and opinions thoughtfully, avoiding personal attacks or offensive language. Strive to provide accurate and reliable information by double-checking facts before posting. Constructive discussions help everyone learn and make better decisions. Thank you for contributing positively to our community!

6 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Regarding the statement: “The public mood would also have to shift from anti-pipeline, anti-development, to one that embraces pipelines, water diversion projects, and Arctic infrastructure building as sources of national pride.”

It is not the public mood that needs to shift at all. Our nations development has been stalled for years by an idiotic New World Order aligned Liberal government bent on implementing Net Zero ideology and impractical ‘green energy’ that is anything but green. Sadly, if Carney is installed in the coming federal election, that madness will continue.

Are John Q public not the ones who keep electing liberals?

Rick

So much potential!

It’s about time we get realistic and get started.

Could not agree more!

Rick

This is very attention-grabbing, You are a very professional blogger.

I have joined your feed and sit up for in search

of extra of your great post. Also, I have shared your web site

in my social networks

I’m extremely impressed together with your writing

talents as well as with the layout to your

weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you customize it your self?

Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it’s rare

to see a nice weblog like this one today..