Called for lithium tsunami cancelled

2019.02.23

The prevailing theme for the lithium market over the past several months has been falling prices in China, the top lithium consumer due to its dominance over the electric vehicle/ EV battery market. The country represents half of global EV sales and Chinese company CATL is the largest EV battery maker in the world.

Indeed prices of lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide – both can be used in the EV battery cathode – have dropped. Lithium carbonate now sells for about $12,000 a tonne, 50% less than a year ago, while lithium hydroxide goes for around $16,000/t in China compared to $20,000/t six months ago.

On top of that, production of spodumene – the hard-rock mineral containing lithium – from new mines in Australia is causing a glut in China, putting downward pressure on spodumene prices. That’s good for lithium processing companies that convert the spodumene to lithium hydroxide, but bad for Australian spodumene miners.

According to Benchmark Intelligence, a good tracker of the lithium industry, combined output at four new lithium operations totaled over 175,000 tonnes, with production still climbing. All these mines are in Australia.

The biggest spodumene mine in the world, Greenbushes, also in Australia, apparently is doubling production, which will only add to the spodumene supply glut.

The 6% spodumene concentrate is shipped to China where it is converted into saleable lithium hydroxide, for use in batteries. That spodumene fetched around $900 a tonne last year but it’s down to as low as $620/t, according to Benchmark.

The other underlying market theme is falling stock prices. Albemarle’s shares are selling for $30 less than a year ago, Tianqi Lithium’s stock is around half of what it was worth in February 2018, as is Orocobre’s. Perth-based Galaxy Resources has fallen around a buck, from $3.11 a share to $2.12/sh during the same period.

You’d expect that, considering the prices of all three lithium commodities – carbonate, hydroxide and spodumene – have slumped.

But this week I saw something that made me go, “huh?” The world’s number one lithium producer, Albemarle, hit some stellar numbers in reporting its fourth-quarter results. Galaxy and Orocobre also did well, despite Orocobre only getting a price of $10,587 per tonne FOB (free on board) for lithium carbonate shipped out of Argentina.

Not only that, it turns out that Albemarle is very bullish on lithium for the rest of 2019 – predicting that supply will not catch up with demand, leading to higher prices. Of course they would say that, but let’s take a hard look at what’s happening in the lithium market to see if it’s true. Has lithium turned a corner?

A banner Q4

Albemarle stunned lithium market observers with the release of its fourth-quarter and full-year results, Wednesday. Despite the above-mentioned price drops, ALB beat analyst expectations by posting a $1.21 per share profit in Q4 compared to a $1.95/sh loss in Q4 2017. Adjusted earnings were $1.53/sh, bettering the $1.46 expected by analysts.

The full-year numbers were even more dramatic. Albemarle raked in profits of $693.6 million, or $6.34/sh, compared to $54 million, or $0.49/sh, in 2017. That’s a gain of nearly 12x!

Sales from ALB’s lithium unit (the chemical company produces other industrial chemicals) were up around 18% year over year to $341.6 million, on higher volumes and higher prices.

In a conference call talking about Albemarle’s Q4 earnings, CFO Scott Tozier said “Volume growth for the full year 2018 was 10% and prices improved by 9%, driven by the increasing demand of our contracted customers for battery-grade materials.” Fourth-quarter prices were up by an average 4% compared to Q4 2017. Lithium represented just over half of Albemarle’s adjusted earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA).

Higher prices? I thought lithium prices went down. Well here lies the answer to that conundrum:

The disconnect between lower lithium carbonate and hydroxide prices quoted in China, and 10% higher prices realized by Albemarle selling most of its lithium – about 40,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate a year – from La Negra in Chile, can be explained by the fact that major lithium producers sell lithium on long-term contracts, much like how uranium miners sell U308 to nuclear utilities.

The Chinese spot price is just one of many lithium prices quoted, depending on the route the lithium is shipped on and the percentage of lithium. Reuters notes that the price of lithium in large-volume contracts has been rising since 2015. The confusion over lithium pricing in fact has the London Metal Exchange considering creating a futures market for lithium, which would change the way lithium is priced in a similar way that iron ore moved from a system of quarterly contracts to a futures market.

Like us, Charlotte, NC-based Albemarle isn’t buying the arguments of lithium bears; it’s predicting another banner year. The 2019 outlook sees adjusted earnings from $6.50 to $6.80 a share – a year over year increase of 11-19%.

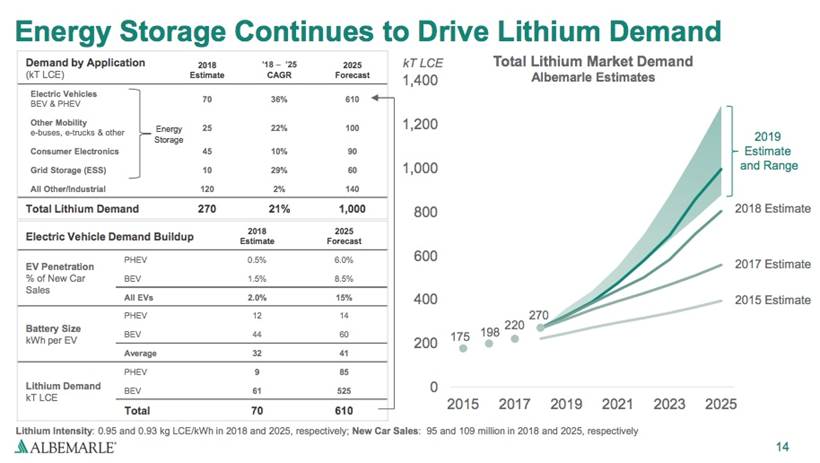

Net sales should grow from between $3.65 billion to $3.85 billion, or 8-14%, driven by higher lithium sales, based on 21% growth in global lithium demand, as manufacturing of electric cars and large-scale batteries soars.

Albemarle is expecting demand for lithium carbonate equivalent to be about 475,000 tonnes by 2021 and a million tonnes by 2025. Currently, global lithium production is about 280,000 tonnes.

“The momentum around electric vehicles has continued to accelerate,” Tozier said. “The demand curve has shifted higher and steepened.” He therefore expects the market to remain tight in the coming years.

“We are not forecasting any significant macroeconomic headwinds and have not seen any decline in our customer demand forecasts,” added Luke Kissam, Albemarle’s CEO, in the quarterly report.

Albemarle’s competitors also saw good results from their earnings reports. Orocobre, which operates the Olaroz Lithium Facility in Argentina, upped its production 65% compared to the year-ago quarter, and despite seeing lower sales revenue and prices, managed to nearly double its profit – for the second half of 2018 – from $8.2 million during the first half, to $15.2 million. The company produced a half-year 6,075 tonnes of lithium carbonate.

Notably, the average price Orocobre received for its lithium during H2 2018, was $12,295 a tonne versus $11,415/t in the previous half-year.

Galaxy Resources which operates the Mt. Cattlin spodumene mine in Western Australia, mined 9% more ore and sold 34% more concentrate, 39,682 dry tonnes, in the fourth quarter compared to the year-ago quarter, Galaxy said in an operational update.

So, the major lithium producers are doing well, even though their share prices don’t reflect it, and despite the downturn in lithium prices.

The latest price data from Fastmarkets MB shows battery-grade spot lithium prices are holding steady (virtually unchanged from a week ago), with the all-important China prices listed below:

- 99.5% Li2CO3 lithium carbonate US$10,872 to $12,063/t

- 56.5% LiOH.H2O lithium hydroxide: $14,298 to $15,638.t

- 5-6% Li2O spodumene: $600 to $750/t

The lithium bears

A year ago investment bank Morgan Stanley came out with a damning report on lithium; its research team concluded that an avalanche of lithium was in the works and would put the roughly 280,000 tonnes per year lithium market into surplus. The glut would mean a fall to around US$13,000 a ton in 2018, halving to $7,000/t by 2021.

“A host of lithium projects and expansion plans – including increased production by low-cost Chile brine operator SQM – threatens to add 500 kilo-tonnes per annum to global lithium raw material supply by 2025, swamping forecast demand growth,” Morgan Stanley said.

The main reason for Morgan Stanley’s argument for oversupply was the government approval in Chile for mine expansions which would “open up the floodgates” to new lithium product.

The next lithium bear to wake up was commodities researcher Wood Mackenzie, which forecast a rout in lithium and cobalt – both key ingredients in EV batteries. While Woodmac didn’t lowball demand growth – expecting it to grow from 233,000t lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) in 2017 to 330kt in 2020 and 405kt in 2022 – it too forecast an imminent tsunami of lithium supply.

The London-based firm predicted prices would slip from $13,000 per tonne in 2018 to $9,000 by 2019 and keep dropping to $6,500 in 2022.

A third report from Moody’s projected a lithium supply build-up to 2025, based on a mine-by-mine analysis, would push lithium prices down in the early 2020s.

What the bears seem to have in common is the belief that a rush of new lithium supply will soon hit the market, but what the analysts don’t realize, or maybe for their own reasons neglect to mention, is that a lot of these mines will fail to deliver.

New lithium mines face daunting economic and technical challenges. A major factor affecting capital costs for lithium brines is the net evaporation rate – this determines the area of the evaporation ponds necessary to increase the grade of the plant feed. These evaporation ponds can be a major capital cost. The lithium-pregnant solution is pumped to an extraction plant where impurities like boron and magnesium are removed. High magnesium percentages can kill the economics of a brine operation.

Hard rock lithium miners have large problems facing them when competing with brine economics – firstly most have large capital costs for start-up and secondly their production costs are roughly twice what it is for brines.

Lithium products derived from brine operations can be used directly in end-markets, but hard-rock lithium concentrates need to be further refined before they can be used in value-added applications like lithium-ion batteries ie. the spodumene must be processed into lithium hydroxide.

We know that between 2012 and 2016 major lithium miners planned to produce an extra 200,000 tonnes of new supply. But when 2016 rolled around, under 50,000 new tonnes came online, due to technical problems getting the lithium to market.

A change in tides is not a tsunami

The same thing happened in 2018.

According to Benchmark Intelligence, the predicted supply expansions in 2018 – including from South American brine operations, new spodumene mines and Chinese lithium production – were slower than expected:

“The ‘tsunami’ of new supply forecast by some has turned out to be little more than a changing in the lithium tides.”

In a January 2019 report, Benchmark reminds us that SQM encountered a technical obstacle at its conversion facilities, which delayed a targeted capacity increase to 70,000 tonnes per annum.

An even bigger disappointment, in terms of higher output, was Chinese production from the Qinghai region. High magnesium concentrations are a problem and “only an additional 5,000-10,000 tonnes of material found its way to market, much of which only reached technical grade specifications. This meant a large proportion was either reprocessed (adding cost) or converted to hydroxide to meet the growing demand for nickel rich cathode technologies,” states the report.

Regarding spodumene mines, while the four new Australian mines are on track to produce over 20,000 tonnes of LCE by the end of this year, by Benchmark’s calculations, less than half of that amount made its way to the market in 2018.

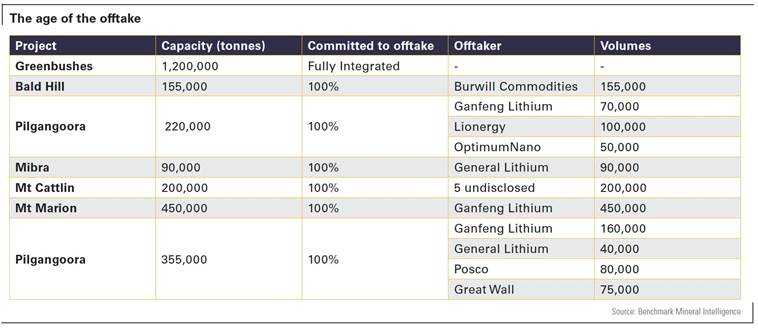

Another important factor here is offtake agreements. As we pointed out in a recent article, all present and future production from Australian lithium mines has been spoken for, which reduces the amount of spodumene on the spot market – putting upward pressure on prices.

An example is the Mt. Marion mine. The mine’s 52,000-tonne increase last year was absorbed by Ganfeng Lithium’s new lithium hydroxide facility.

Benchmark notes that the “rapid development” of four new spodumene operations in the space of 12 months has come at a price: “dependence on offtake agreements and partnerships which will tie in the majority of their production for the foreseeable future.”

“Entering 2019, 100% of spodumene capacity is either tied to offtake or fully integrated in the case of Greenbushes.”

According to Benchmark, with all of the spodumene supply locked up (Nemaska’s new lithium mine in Quebec has offtakes in place too), “there is likely to be less than an additional 80kt LCE equivalent enter the supply chain in 2019.”

What is clear is that there is a still a long way to go to reach the 1m tpa lithium threshold the industry is expected to exceed by 2026.

Even if the market moves into excess in 2019, battery demand dictates that supply and demand will be finely balanced for the foreseeable future.

The old commodities axiom, “the cure for low prices is low prices,” holds true here. Since the publication of our article on the current spodumene glut, we’ve already seen one mine drop out because prices are too low.

On Feb. 20 North American Lithium stopped production at its La Corne hard-rock lithium mining operation in Quebec, due to low Chinese spodumene prices. The mine which produced 140,000 tonnes last year is expected to remain idle until the summer. That’s about 50,000 tonnes that won’t add to the supply glut.

On the brine side, heavy rains in Chile and Argentina have dented production for both Orocobre and Albemarle. A recent deluge at the Australian company’s Salar de Oroz facility in Argentina means that it won’t be able to lift production as previously anticipated, with output not expected to exceed last year’s 12,470t.

Albemarle said in its conference call that a dilution in the pond system from heavy precipitation will cost the company about 3,000t of production.

Conclusion

“What is expected is not always delivered.” This pithy phrase is a good summary of lithium supply. Lithium mining isn’t like mining copper, lead or even precious metals, which typically require extra processing. Getting it right requires time, money and a fine chemical balance. This is why lithium mines, especially new ones, need time to develop their flow sheets and work out the kinks. With seven spodumene mines now operating in Western Australia, it will be interesting to see whether their targets are met this year. History tells us they probably will fall short.

We already know that Salar de Oroz in Argentina will only produce about 12,500t this year – just over a quarter the output of Albemarle’s La Negra mine in the Salar de Atacama. North American Lithium’s mine is out until summer. Commissioning of the Mt. Holland lithium mine in Australia is halted while they sort out issues with endangered species. Nemaska Lithium’s Whabouchi lithium mine and Shawinigan electrochemical plant in Quebec isn’t doing anything until Nemaska comes up with a way to fund a $375 million shortfall.

Chile is closely watching the use of water in the Salar de Atacama and has not been shy about imposing water restrictions, which could impact production – lithium brine mining requires a lot of water. Last fall the government refused to increase Albemarle’s production quota or grant it a license for building a half-billion-dollar processing plant. The two parties recently came to a resolution allowing for Albemarle to expand, but the hassle shows that Chile is willing to make it difficult for foreign mining companies to extract what it considered to be a strategic resource; state-owned SQM faced no such obstacles to expanded output.

Putting it all together, it seems clear to us, at Ahead of the Herd, that a promise to supply lithium is by no means a guarantee; there are many factors at play that can easily blow a hole in output forecasts. We’ll stick with Albemarle’s call on the lithium market tightening this year, purely from a supply point of view that “What is expected is not always delivered.”

And we haven’t even talked about demand:

- 24% growth in EVs every year until 2030.

- 54-fold increase in EVs between 2017 and 2040, when global light-duty EV sales are expected to hit 60 million, 15x more than the current 4 million.

- 68 lithium-ion battery mega-factories already in the planning or construction stage.

The way things are going, lithium bears may never come out of hibernation.

Richard (Rick) Mills

Ahead of the Herd is on Twitter

Ahead of the Herd is now on FaceBook

Ahead of the Herd is now on YouTube

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

This document is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, I, Richard Mills, assume no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this Report.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.