Biggest copper mines produced 20% less copper in 2023 – Richard Mills

2024.04.06

Copper jumped to $4.24 a pound ($9,359.23 a tonne) on Friday, the highest in 14 months.

The rally began in early February on mounting risks to supply.

At the same time, there has been a return to growth in the manufacturing sector, which has strengthened demand for copper.

The base metal is used in a plethora of manufacturing processes, so commodity analysts keep a close eye on manufacturing data to get an idea in which direction copper prices are headed.

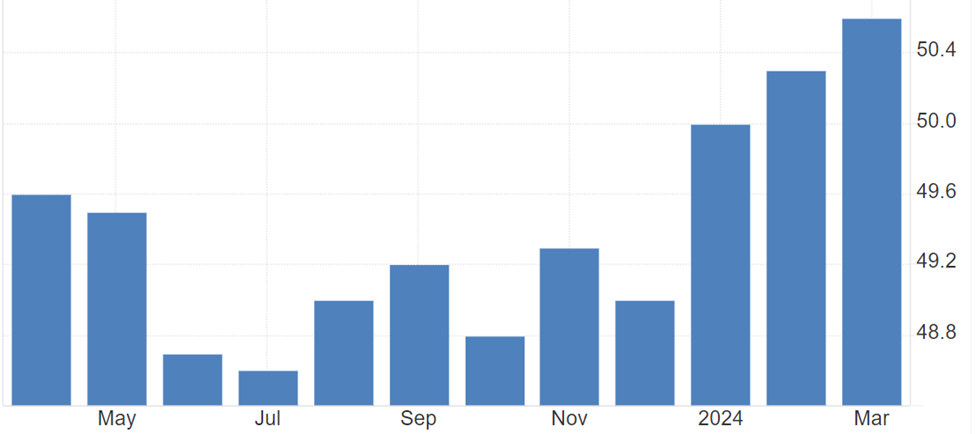

Global purchasing managers’ indices show that factory orders bottomed in January and are moving back up.

The JPMorgan Global Manufacturing PMI was a neutral 50 in January — anything above 50 reflects an expansion — halting a 16-month streak of sub-50 readings, and ticked up to 50.3 in February.

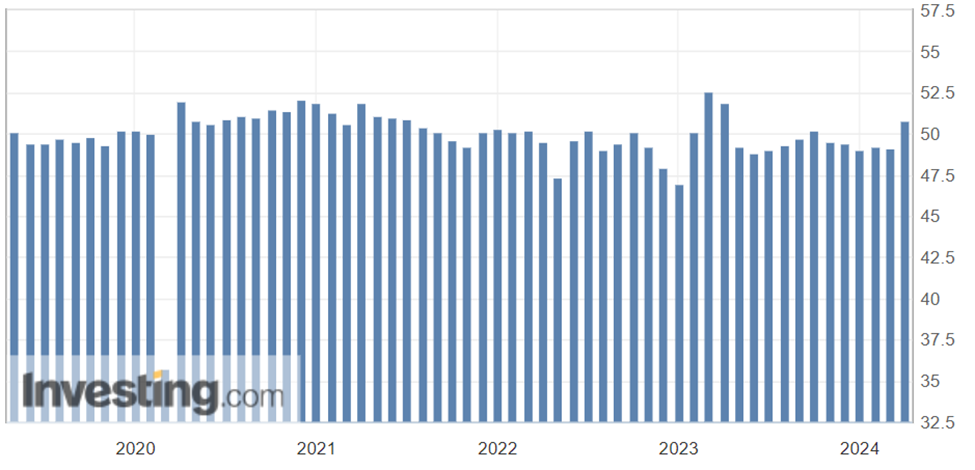

The S&P Global US Manufacturing PMI was 52.2 in February, with US manufacturing conditions improving at the fastest pace since July 2022, and bettering January’s 50.7. The March numbers were even better, rising to a 21-month high of 52.5.

According to Bloomberg,

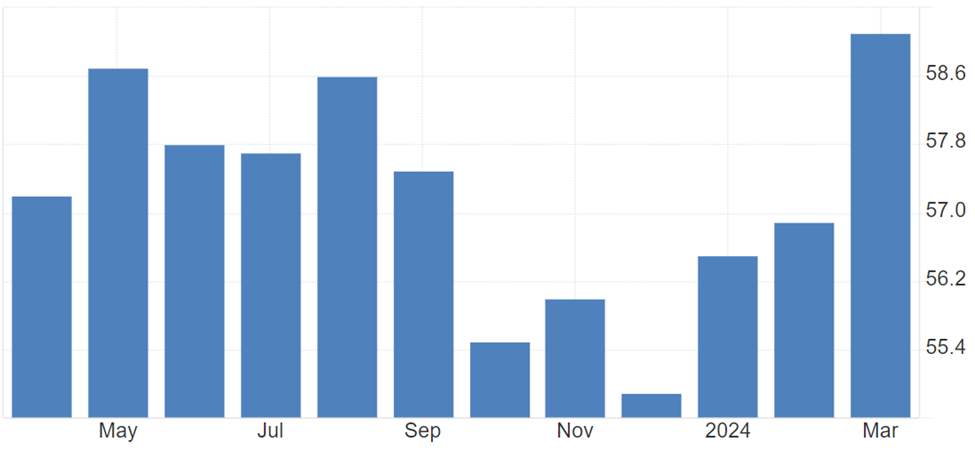

In China, the official manufacturing purchasing managers’ index expanded in March for the first time since September, while preliminary data from India points to some of the strongest growth for the industry in years.

That’s catapulted the commodity to the highest prices in more than a year, up almost 9% so far in 2024.

Supply disruptions

Production concerns began late last year, when the government of Panama ordered First Quantum Minerals to shut down its Cobre Panama operation, removing nearly 350,000 tonnes from global supply.

A strike at another large copper mine, Las Bambas in Peru, temporarily halted shipments. Copper specialist Anglo American now says it is scaling back output by about 200,000 tons, owing to head grade declines and logistical issues at its Los Bronces mine.

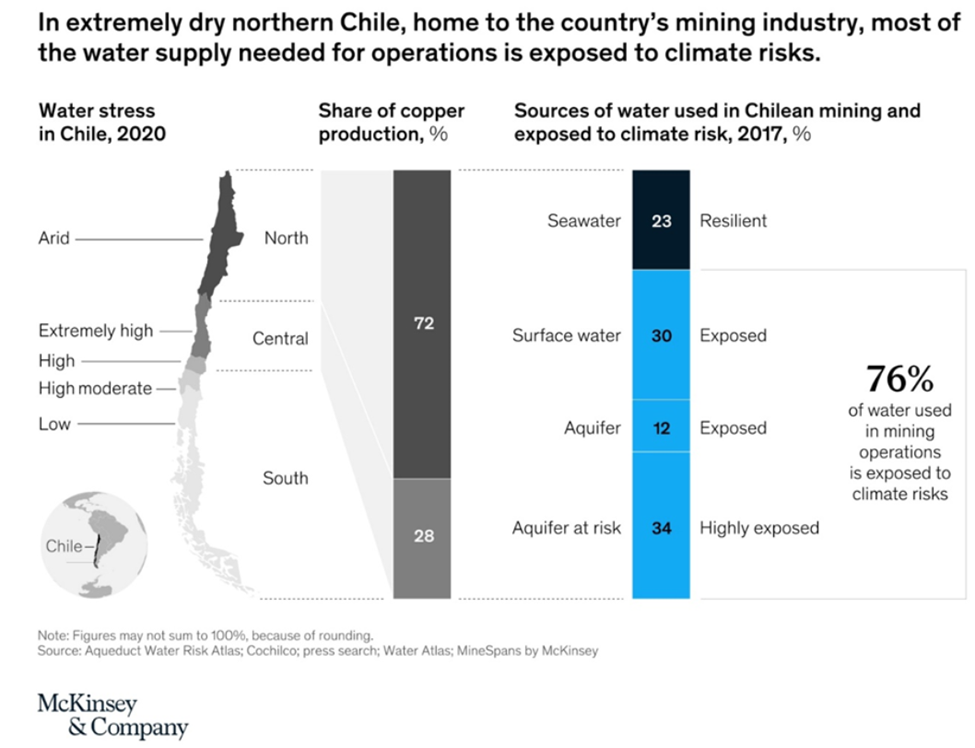

Chile’s copper output has been dented by a long-running drought in the country’s arid north. State miner Codelco’s 2023 production was the lowest in 25 years.

All four of Codelco’s megaprojects have been delayed by years, faced cost overruns totaling billions, and suffered accidents and operational problems while failing to deliver the promised boost in production, according to the company’s own projections.

There are also concerns about Zambia, Africa’s second largest copper producer, where drought conditions have lowered dam levels, creating a power crisis that threatens the country’s planned copper expansion.

Finally, this week Ivanhoe Mines reported a 6.5% quarterly drop in production at the world’s newest major copper mine, Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC.

All these supply interruptions have left Chinese copper smelters paying steep prices for mined ore, leading them to consider a joint output cut in response.

In a nutshell, there are too many smelters and not enough imported raw copper ore to feed them.

The world’s 20 biggest copper mines

We decided to dig deeper into the supply cuts to get an idea of how much copper is actually being produced. Our analysis confirmed suspicions that it is considerably less than a few years ago.

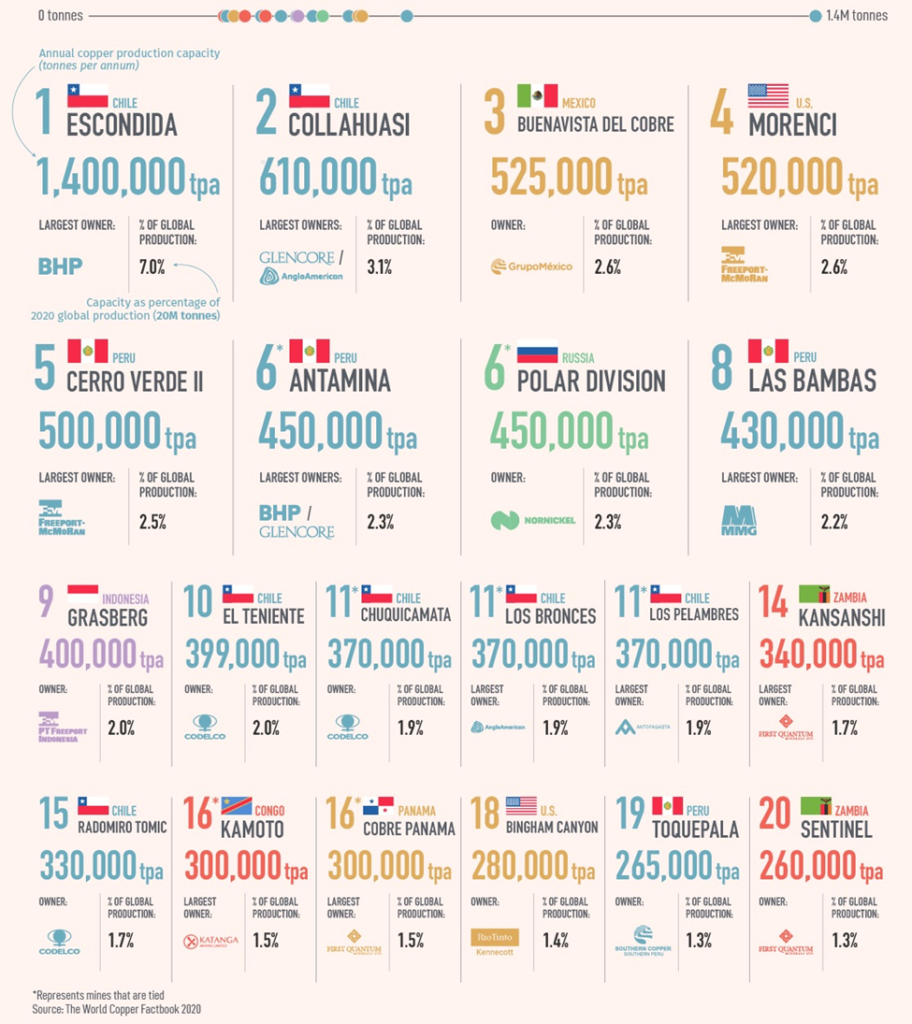

Our first step was consulting Visual Capitalist’s 2021 graphic of the world’s 20 largest copper mines by production capacity.

The figure below shows Escondida in Chile leading the pack, at 1.4 million metric tons capacity per annum, through to number 20 First Quantum’s Sentinel mine in Zambia with its 260,000 tpa capacity. Five of the 20 mines “tied” for having the same amount of capacity.

These 20 mines have the capacity to produce nearly 9 million tonnes of copper annually, representing 44% of global production in 2020.

How much did they actually produce in 2023?

AOTH combed through quarterly and annual reports, press releases and news articles to find out.

Of the mines we could find 2023 production figures for, the total came to 5,818,792 tonnes. Only two — now-shuttered Cobre Panama and Grasberg (Freeport McMoRan’s 231,836t +204,960t estimated production from PT Inalum and PT Indonesia based on 51.24% ownership) — produced more than their 2020 production capacities. The rest produced less.

We had to find a way to compensate for the missing data for six mines. We decided to use each individual mine’s 2020 production capacity as the (missing) 2023 production figure. For example, no figures were found for Southern Copper’s Buenavista mine in Mexico, so for 2023 we used its 2020 production capacity of 520,000 tonnes. This generously estimates the amount of copper that was actually produced last year, since most, if not all of these mines with missing data likely produced less than their production capacity.

Adding 1,592,960 tonnes of estimated 2023 production (for six mines) to the 5,818,792 tonnes of actual 2023 production for the remaining 14 mines gives a total of 7,411,752 tonnes — 19.6% less than 2020’s total capacity for the world’s top 20 mines of 8,869,000 tonnes.

Consult the list below for production details of each mine:

1 – Escondida

2023 production 1,055,000 tonnes

2024 guidance 1,080 –1,180 tonnes

2020 production cap 1,400,000 tonnes

Escondida in Chile, the world’s largest copper mine, is jointly owned by BHP (57.5%), Rio Tinto (30%) and 10% by Japan’s JECO Corp. The copper-gold-silver mine is located in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, where two pits feed three concentrator plants and two leaching operations, one oxide and one sulfide.

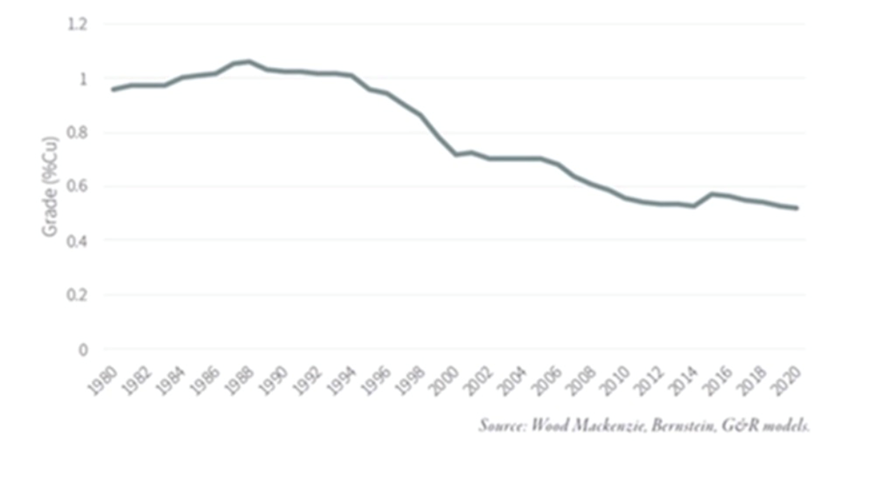

According to BHP, in 2023, Escondida copper production increased by 5 per cent to 1,055 kt primarily due to higher concentrator feed grade of 0.82 per cent, compared to 0.78 per cent in FY2022. The positive impact of the higher grade was partially offset by the impact of road blockades across Chile as part of civil unrest in the December 2022 quarter, which reduced availability of some key mine supplies. Full-year production came in at the low end of revised guidance largely as a result of measures implemented to manage geotechnical events in a high-grade section of the Escondida pit. These included a resequencing of the mine plan, resulting in lower-than-anticipated volumes of mined ore and increased processing of lower grade stockpiles through the concentrators.

In April 2023, BHP downgraded its production guidance in the year through June to between 1.05 million and 1.08 million tonnes, from 1.08Mt to 1.18Mt previously.

Rio Tinto’s share of mined copper production from Escondida was flat last year at 300,000 tonnes.

2 – Collahuasi

2023 production 573,200 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 610,000 tonnes

The Collahuasi mine is located in the north of Chile’s Tarapaca region. It has one of the largest copper reserves in the world, estimated at 3.93 billion tonnes grading 0.66% copper.

Anglo American and Glencore each own 44% while the remaining 12% is held by Japan Collahuasi Resources B.V.

According to Anglo American, the mine produced 573,200 tonnes in 2023.

3 – Buenavista del Cobre

2023 production (not found)

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 525,000

The Buenavista mine is a large open pit located in northwestern Mexico. It lies 35 south of the US-Mexico border near Nogales, Arizona.

According to owner Southern Copper Corp, a 13.5% decrease in production at Buenavista was mainly driven by lower ore grades and recoveries. This was offset by the positive impact of an uptick in production at Toquepala (see number 19 below).

A recent Reuters story says parent company Grupo Mexico expects to produce 1.058 million tons of copper in 2024, up from 1.03 million tons last year. Full-year 2023 copper production was up 2% year on year, falling short of its prior target of 1.05 million tons.

4 – Morenci

2023 production 362,873 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 520,000 tonnes

Morenci is an open-pit copper mining complex in Arizona that has been in continuous operation since 1939.

US copper giant Freeport McMoRan owns 72% of Morenci, with Sumitomo Metal Mining Arizona owning 15%, and SMM Morenci holding 13%.

According to Freeport’s annual report, Morenci’s 2023 copper production, including Freeport’s joint venture partners’ share, totaled 0.8 billion pounds, or 362,873 tonnes. The mine produced 0.9 billion pounds of copper in both 2022 and 2021.

5 – Cerro Verde

2023 production 453,592 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 500,000 tonnes

Cerro Verde Copper Mine is an open-pit copper and molybdenum mining complex located 32 km southwest of Arequipa in Peru.

Freeport McMoRan through its subsidiary Cyprus Climax Metals, owns a 53.56% stake in the mine and SMM Cerro Verde Netherlands, a subsidiary of Sumitomo Metal Mining, holds 21%, while Buenaventura and others have 19.58% and 5.86% stakes, respectively.

According to Reuters, copper production in Peru, the world’s third largest producer of the metal, slipped 1.2% in January from a year earlier to 205,375 tonnes.

The new figures come after a 17% drop in output from MMG’s Las Bambas mine and a 13.4% fall from Freeport-McMoRan’s Cerro Verde mine.

According to Freeport’s annual report, Cerro Verde’s copper production last year totaled 1 billion pounds, or 453,592 tonnes. BNAmericas notes that, Although Peru’s copper output reached a record 2.76Mt in 2023, miners like Cerro Verde reported reductions due to lower ore grades.

Freeport projects lower sales volumes from its South American units in 2024, with the Cerro Verde copper mine in Peru contributing less.

It says the region will generate a total sales volume of 1.13 billion pounds (512,559t) of copper in 2024, down from 1.20Blb sold in 2023, according to Freeport’s latest results presentation.

Freeport said the drop was due to lower grades at Cerro Verde in the Arequipa region of Peru.

6 – Antamina

2023 production 376,100 tonnes (omitting Mitsubish’s 10%)

2024 guidance (Teck 85-95kt, BHP 120-140kt)

2020 production cap 450,000 tonnes

The Antamina copper and zinc mine is located high in the Andes at an average elevation of 4,200 meters, 270 kilometers north of Lima, Peru.

Teck Resources has a 22.5% interest in the mine, with BHP and Glencore each owning 33.75% and Mitsubishi Corp owning 10%.

According to production reports, the mine in 2023 produced 376,100 tonnes of copper, including 95,300t from Teck, 138,400t from BHP, and 142,400t from Glencore. Mitsubishi’s production figures were not found. Glencore’s Q42023 report says production at Antamina was down 7% from 2022 due to lower grades.

Teck’s 2024 guidance is 85,000 – 95,000 tonnes, and BHP’s is 120,000 to 140,000 tonnes.

7 – Polar Division

2023 production (no figures available)

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production 450,000

8 – Las Bambas

2023 production 302,033 tonnes

2024 guidance 280,0000 – 320,000 tons

2020 production cap 430,000

The Las Bambas Mining Unit is located in the Apurímac region of Peru, about 75 km southwest of Cusco.

Las Bambas is a joint venture between the operator MMG (62.5%), a wholly owned subsidiary of Guoxin International Investment Co. Ltd (22.5%) and CITIC Metal Co. Ltd (15%).

Earlier this year, Reuters said MMG predicted that Las Bambas would produce between 280,000 and 320,000 tons of copper in 2024, after putting out 302,033 tons in 2023.

9 – Grasberg

2023 production 231,835 tonnes (omitting PT Inalum’s and PT Indonesia’s 51.24%)

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 400,000 tonnes

The Grasberg copper mine is located in the remote highlands of the Sudirman mountain range in the province of Papua, Indonesia. It includes the Grasberg Block Cave, Deep Mill Level Zone (DMLZ) and Big Gossan underground mines.

48.8% of the Grasberg open pit (PT-FI) is owned by Freeport McMoRan, with 51.24% held by PT Inalum and PT Indonesia.

Freeport’s share of 2023 production was 511 million pounds, or 231,835 tonnes. PT Inalum and PT Indonesia’s portions were not found.

10 – El Teniente

2023 production 351,900 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 399,000 tonnes

El Teniente is the world’s largest underground copper mine, with 3,000 km of underground tunnels and a production of >22Mt since startup.

According to Codelco’s annual results, 2023 (company-wide) production was 1.42Mt compared to 1.55Mt in 2022, a decline of 8.4%.

At El Teniente, copper production was 351.9kt in 2023 vs 405.4kt in 2022, a decline of 13.2%. Codelco said the mine was affected by the Sewell plant shutdown due to a fatal accident, major maintenance at the Colón plant, an unusual weather event in June, and a seismic event during the last week of July.

11 – Chuquicamata

2023 production 248,500 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 370,000 tonnes

Codelco owns and operates the Chuquicamata copper mine in northern Chile; it is one of the world’s biggest open-pit mines.

According to Codelco’s annual results, copper production at Chiquicamata was 248.5kt in 2023 versus 268.3kt in 2022, a decline of 7.4%.

To extend Chuquicamata’s life, the state-owned company is going underground in a project known as Chuquicamata Subterranea,or PMCHS. The $5 billion expansion, originally launched in 2008, was supposed to see construction finish in 2017; instead, completion is delayed until 2025.

According to Reuters, After it was inaugurated in 2019, PMCHS was expected to produce 385,000 metric tons in 2023. Instead, it produced 268,000 in 2022 and just 178,000 in the first nine months of 2023 due to the slower rollout of the project.

12 – Los Bronces

2023 production 215,500 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production 370,000 tonnes

Los Bronces is an open-pit copper and moly mine. The project is part of Anglo American Sur, which is majority owned by Anglo American (50.1%). The Codelco-Mitsui consortium (29.5%) and Mitsubishi (20.4%) are the other stakeholders.

Los Bronces is located around 65 km northeast of Santiago at an altitude of around 4,000m above sea level.

According to Anglo American’s Q42023 results, Q4 production from Los Bronces decreased by 32% to 57,200 tonnes, primarily driven by expected lower grades (0.52% vs. 0.69%) and throughput due to continued ore hardness. 2023 production was 215,500 tonnes vs 270,900 in 2022, a 20% reduction.

13 – Los Pelambres

2023 production 300,300 tonnes

2024 guidance 335,000 – 350,000 tonnes

2020 production 370,000 tonnes

Antofagasta in January reported a 2% rise in 2023 copper production on higher output at its flagship Los Palambres mine in Chile, due to improved water availability. (Mining Weekly, Jan. 17, 2024)

The company’s website says copper production at the mine last year was 300,300 tonnes, 9% higher than 2022.

Higher production is forecast for 2024, @ 335-350kt, due to higher throughput, with increased water availability and ore processing capacity with the Los Pelambres Phase 1 Expansion ramping up.

14 – Kansanshi

2023 production 134,827 tonnes (First Quantum percentage)

2024 guidance 130,000 – 150,000 tonnes

2020 production cap 340,000 tonnes

First Quantum Minerals owns the Kansanshi and Sentinel mines in Zambia and the now-closed Cobre Panama mine.

From its two open pits, Kansanshi produces more copper than any other mine in Africa.

The operation is 80% owned by First Quantum and 20% by Zambian Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM) Investment Holdings. ZCCM’s portion of production could not be found.

According to First Quantum’s annual report, Kansanshi produced 135,000 tonnes in 2023, 11,000t lower than 2022. The company as a whole produced 708,000t last year, a 9% reduction.

The company says Zambian production of 349kt was 10% lower than 2022 due to a combination of lower throughput at both sites and lower grades at Kansanshi.

15 – Radomiro Tomic

2023 production 285,763 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 330,000 tonnes

Another Codelco-owned mine, Radomiro Tomic produced 315,000 tons (285,763 tonnes) of copper in 2023, just under a quarter of the company’s annual production, Reuters said this week.

16 – Kamoto

2023 production (not found)

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production 300,000 tonnes

The Kamoto underground copper and cobalt in the DRC is the largest cobalt mine in the world. It is run by the Kamoto Copper Company, a joint venture comprising Glencore (75%), Gécamines (20%) and Simco (5%).

According to Glencore’s production report, 2023 copper production of 1,010,100 tonnes was 48,000 tonnes lower than 2022 (-5%), primarily reflecting the sale of Cobar [mine in Australia] in June 2023 and lower copper by-product production outside the Copper department.

17 – Cobre Panama

2023 production 331,000 tonnes

2024 guidance 0

2020 production cap 300,000 tonnes

Commercial production at Cobre Panama began in 2019. Four years later, following public protests against it on environmental grounds, the country’s Supreme Court annulled the deal between the government and First Quantum Minerals, ordering the mine closed. Its 2023 production of 331,000 tonnes exceeded 2020’s production capacity.

18 – Bingham Canyon

2023 production 151,600 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 280,000 tonnes

The Bingham Canyon/ Kennecott mine is located just outside Salt Lake City, Utah. The operation owned by Rio Tinto subsidiary Kennecott Utah Copper LLC includes a concentrator, smelter and refinery and tailings storage facility.

According to a company filing, Kennecott produced 151,600 tonnes in 2023.

Last June Bloomberg reported the Rio Tinto Group expects to invest about $920 million in the mine, including $498 million to develop an underground mine and infrastructure in the North River Skarn, which will deliver about 250,000 tons of copper over the next 10 years. Production from the new operation will begin this year.

19 – Toquepala

2022production 201,485 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 265,000 tonnes

Toquepala is a porphyry copper mine located in the Peruvian Andes. It mainly hosts copper, molybdenum and silver, with minor gold and zinc deposits.

The mine consisting of an open pit, a concentrator plant, and a refinery facility dedicated for extraction and electrowinning (SX-EW), is owned and operated by Southern Peru Copper Corporation (SCC), a Grupo Mexico company.

According to Southern Copper’s latest annual report, 2022 production at Toquepala was 201,485 tonnes.

20 – Sentinel

2023 production 214,046 tonnes

2024 guidance (not found)

2020 production cap 260,000 tonnes

The Sentinel open-pit mine in Zambia is one of Africa’s biggest copper mines. Producing since 2016, Sentinel is owned and operated by Kalumbila Minerals, a subsidiary of First Quantum Minerals.

The mine produced 214,046 tonnes in 2023.

Conclusion

2024 is so for proving to be a great year for copper; the red metal is up almost 9% year to date.

Most important is supply failing to keep up with demand. The second factor is a weakening of the US dollar if market expectations of monetary easing come to pass. Third is the return of the manufacturing sector, with PMIs indicating the world economy is expanding.

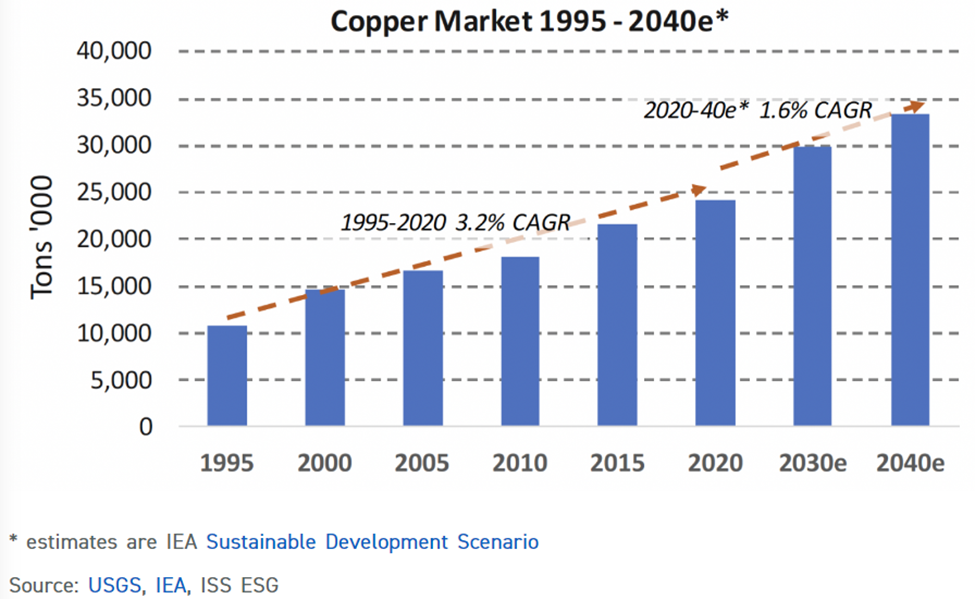

Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (BMI) forecasts global copper consumption to grow 3.5% to 28 million tonnes in 2024, and for demand to increase from 27 million tonnes in 2023 to 38 million tonnes in 2032, averaging 3.9% yearly growth.

Yet, the US Geological Survey reports supply from copper mines in 2023 amounted to only 22 million tonnes. If the copper supply doesn’t grow this year, we are looking at a 6Mt deficit.

As our calculations show, that 22 million tonnes of production reflects roughly a 20% reduction in output from the top 20 copper mines. If supply interruptions continue in some of the top producers, like Chile, Peru, Zambia and the DRC, the deficit could grow even bigger, and likely will. This week we learned that the Congo’s Kamoa-Kakula mine experienced a 6.5% quarterly drop in production. More labor unrest at Las Bambas in Peru is looming. Chile continues to have water problems and according to the International Energy Agency, average copper grades there have declined by 30%.

Wall Street commodities investment firm Goehring & Rozencwajg says the industry is “approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades and brownfield expansions are no longer a viable solution. If this is correct, then we are rapidly approaching the point where reserves cannot be grown at all.”

The importance of making new discoveries in establishing a sustainable copper supply chain is obvious.

Exposing the copper surplus myth — Richard Mills

Greenfield additions to copper reserves have slowed dramatically, with tonnage from new discoveries falling by 80% since 2010.

Several large copper mines have mined out all the ore in open pits and are heading underground for the higher-grade, but more-expensive-to-extract material.

Another obstacle to addressing the copper deficit is the fact that four of the five new large mines/ expansions have offtake agreements already in place. The five are Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC, Cobre Panama, and expansions at three existing Chilean mines — Escondida, Spence, and Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca (QB2).

Our analysis showed in the case of Kamoa-Kaukula, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project. Nearly half of Cobre Panama’s annual production was going a Korean smelter under a 2017 offtake agreement. That mine shut down last fall, eliminating nearly 350,000 tonnes of annual production.

Escondida and Quebrada Blanca are both partially owned by Japanese companies — one can assume that a corresponding percentage of production will be going there.

Fact is, the West has almost no off-take agreements in place for 80% of the world’s future copper supply.

That supply is locked up. It’s been previously stated that we need to find 6 million more tonnes of copper, 1 million per year of new copper production if we want to alleviate the deficit — the equivalent production of one Escondida mine each year — but only one of the five mines, Kamoa, has the capability of producing close to that much copper. But Kamoa’s production is going to China.

At AOTH we make a clear distinction between global copper supply and the global copper market. Mined copper that is locked up by offtake agreements should not rightly be lumped in with global supply, because it will never reach the United States, Canada or Europe. Instead, this copper will go straight to smelters in China for use in Chinese industry, to South Korean smelters for South Korean industry, and to Japanese smelters for Japanese industry.

Every year, between 800,000 and 1 million tonnes of copper supply doesn’t make it to market, due to various reasons: strikes, weather, water shortages, accidents, technical problems, low grades, etc.

Some of the world’s largest mining companies, market analysis firms and banks are warning that by 2025, a massive shortfall will emerge for copper, which is now the world’s most critical metal due to its essential role in the green economy.

We have clearly reached the point where we need to find more copper mines, preferably large-scale. Anything less than 200,000 tonnes a year won’t even make a dent in the supply deficit.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.