Behind the US manufacturing boom – Richard Mills

2023.12.06

Manufacturing has always been an integral part of American life. Paul Revere opened a foundry that produced bells and cannons following his famous midnight ride. Henry Ford’s assembly line made cars affordable to the masses. And U.S. industrial might helped win World War II, when nearly half of private-sector employees worked in factories.

That portion plunged after the war, thanks to automation and U.S. companies seeking lower costs overseas. Production capacity, which had grown at about 4% a year for decades, flattened after China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization. — The Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2023

The offshoring of American jobs to China and other low-cost labor jurisdictions was a key talking point during Donald Trump’s bid for the presidency in 2016.

His website in 2017 declared, “America has lost nearly one-third of its manufacturing jobs since NAFTA and 50,000 factories since China joined the World Trade Organization.”

With his ‘America First’ mantra, Trump claimed he could revitalize industries that had been in decline for decades, notably steel, coal and automaking. China’s dumping of cheap steel was Trump’s rationale for a trade war with China (and other countries) in which he introduced tariffs or increased existing ones on Chinese imports worth billions. China naturally replied with a similar amount of countervailing duties. The tariffs, which remain nearly four years after Trump left office, have made Chinese goods more expensive for US consumers, while the duties on American exports have hurt US businesses like agriculture.

It has taken a pandemic and the breakdown of supply chains to really expose US dependency on foreign-made products, and ironically, a Democratic president to revitalize US manufacturing — a bright spot in an economy that many analysts (wrongly, we believe) think is teetering towards recession.

Hard landings, recession predictions wrong

Before we take a deep dive into manufacturing, let’s examine some of the evidence suggesting that the US economy is slowing. (The whole topic is admittedly confusing, since there are multiple data points appearing to contradict one another).

Take a Dec. 4 article by Reuters whose headline screams, ‘US manufacturing mired in weakness, economy headed for slowdown’. A copy editor clearly based the inflammatory title on November’s disappointing manufacturing PMI of 46.7. A number below 50 indicates a contraction. New orders fell from 48.5 to 45.5 and factory employment dropped to 45.8.

Moreover, it was the 13th consecutive month that the PMI was below 50, which is the longest such stretch since August 2000 to January, ’02.

All told, the numbers seem to indicate that the economy is losing momentum after strong growth in the third quarter of 5.2%.

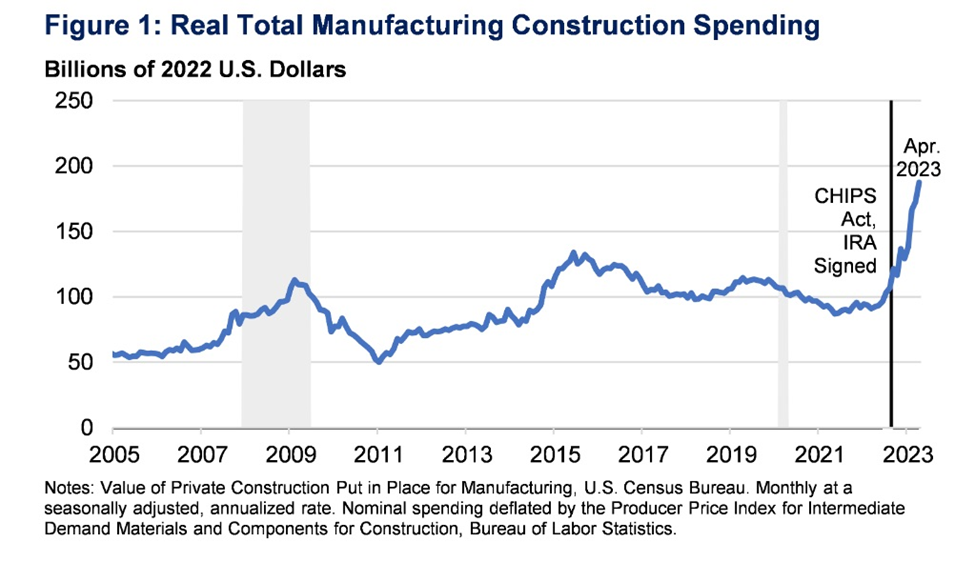

But that’s not the impression one gets after reading an article on Wolf Street titled, ‘The Eyepopping Factory Construction Boom in the US’.

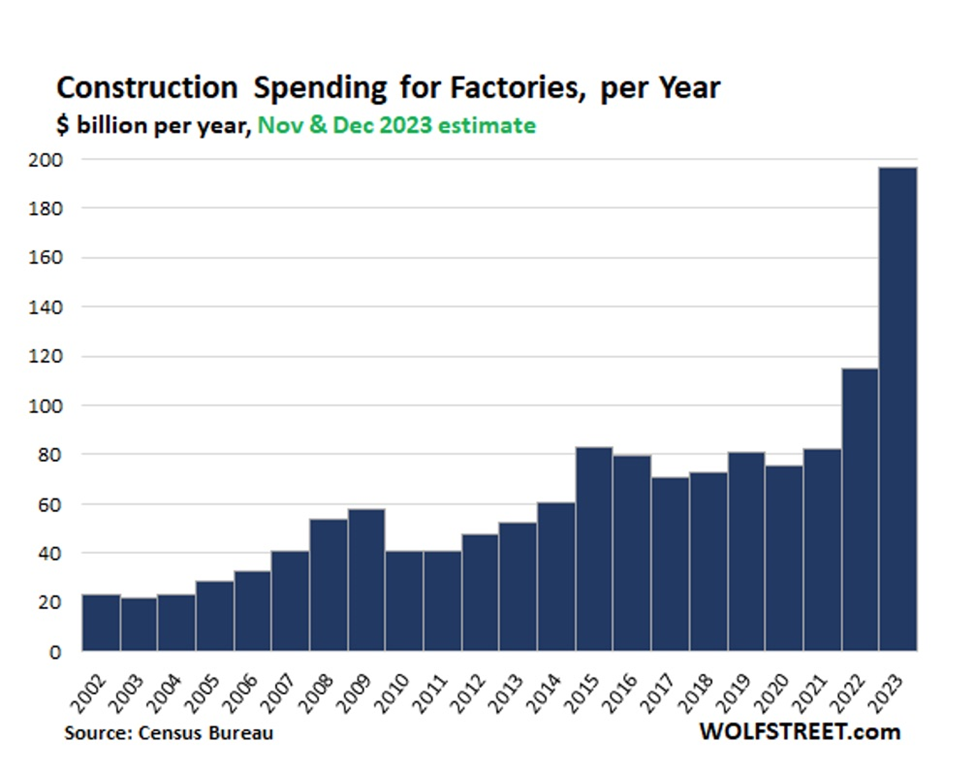

The story by Wolf Richter says $18.5 billion was plowed into construction of manufacturing plants in October, $12.5B was spent in January, and the annualized amount will be $246 billion. For the numerically challenged, that’s nearly a quarter trillion dollars.

Where is all this money coming from? You guessed it: the government.

As Axios points out, the 2010s was a period of chronic under-investment in US heavy industry, compared to now, when there are billions being channeled into megaprojects fueled by the Biden administration’s signature pieces of legislation: the Inflation Reduction Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and the CHIPS and Science Act.

The latter provides about $52 billion in government subsidies for US semiconductor production and an investment tax credit for chip plants estimated to be worth $24B. The legislation would also authorize more than $170 billion over five years to boost US scientific research to better compete with China, Reuters reported in July. It is expected to help fund 10 to 15 new semiconductor factories.

“We believe the U.S. is in the early stages of a manufacturing supercycle,” Axios quotes the head of CIO market strategy at Merrill and Bank of America Private Bank, who emphasizes the role of foreign direct investment in the surge, as global companies rush to build large-scale facilities in the United States. He sees the trend extending well into the second half of the 2020s.

As for why this manufacturing renaissance is happening now, Fox News explains that covid-19, the war in Ukraine, and concerns over China’s annexation of Taiwan, a leader in semiconductors, have driven efforts to reshore manufacturing, reversing a decade-long trend of American industrial capacity moving overseas.

While China’s low labor costs made it an attractive destination for offshoring, that advantage has now vanished due to rising wages. When issues like transportation costs, quality control, and IP theft are added in, “the benefits of globalization have essentially worn off,” Fox News quoted Chris Semenuk, manager of the TEMA American Reshoring ETF.

Among the types of firms likely to benefit from reshoring, electric vehicle batteries and semiconductors are high-profile examples. Others include Ingersoll Rand, which makes compressors used in factories, and Wesco, a provider of electrical and communications equipment.

The United States is mostly clawing back manufacturing capacity from China, although companies in Europe are also moving operations state-side to benefit from incentives offered by the above-mentioned new laws. Semenuk pointed out that Vietnam is reaching its manufacturing capacity limit due to a scarcity of land suitable for large factories.

Now let’s quantify the manufacturing boom.

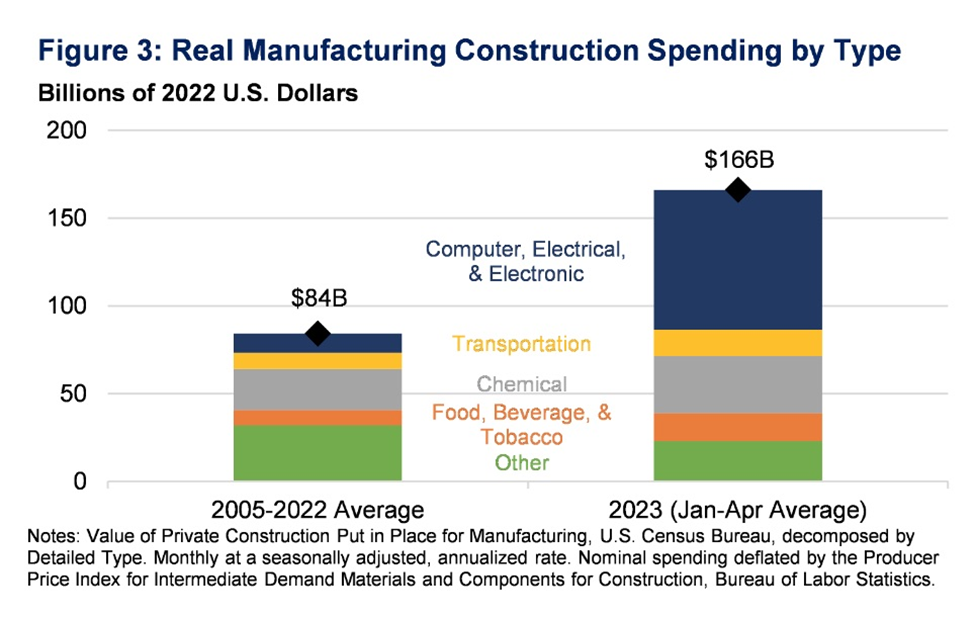

According to the US Treasury Department, real (after inflation) manufacturing construction spending has doubled since the end of 2021, with the boom principally driven by computer, electronic and electrical manufacturing. Real spending for this specific type of manufacturing has nearly quadrupled since the beginning of 2022.”

Census Bureau data shows that construction spending related to manufacturing in 2022 hit a new record of $108 billion.

In an article, the Treasury says “According to Deutsche Bank Research, 18 new chipmaking facilities will have started construction between 2021 and 2023. The Semiconductor Industry Association reports that over 50 new semiconductor ecosystem projects have been announced in the wake of the CHIPS Act.”

The Treasury also states, “Manufacturing construction is one element of a broader increase in U.S. non-residential construction spending, alongside new building for public and private infrastructure following the IIJA [Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act].”

“The IIJA authorized the federal government to distribute new funds to state and local governments for infrastructure needs tied to roads, bridges, public transit, water, and broadband. That funding has started translating to spending.”

(Although, as we pointed out in a previous article, infrastructure spending has been slow to roll out and in fact has declined despite the Biden administration’s high-profile legislation. In the US, there is a $2.5 trillion infrastructure funding gap during the 10-year period from 2020 to 2029, based on figures provided by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). Failure to address it is estimated to result in the loss of $10 trillion in GDP by 2039. According to The Economist, rather than increasing spending to address its infrastructure deficit, US government spending on it has fallen.)

Still, the Treasury says that since the infrastructure bill’s passage, construction spending on roads, bridges, public transit, water, and broadband has outpaced total construction spending. “For example, total construction spending has increased about 4 percent, while public construction spending on the water supply has increased by over 20 percent (Figure 5)….Public spending on highways and streets has also increased by about 13 percent, as the IIJA funds roads, bridges, and major projects with over $110 billion over five years.”

A key point is that real public spending, which increased by 7%, did not crowd out real private spending, which increased by nearly 20% (Figure 4). Real private spending on transportation construction has grown by nearly 14% since the president signed the IIJA.

Wolf Richter in his Wolfstreet.com piece makes the following additional points:

- The supply-chain and transportation catastrophe that CEOs ran into during the pandemic, the edgy relationship between the US and China, and the scary dependence of US companies on Chinese suppliers have triggered a big corporate rethink.

- Manufacturing’s share of GDP had been on a long downward trend in the US. In 2006, manufacturing accounted for over 13% of GDP. By early 2020, manufacturing was down to 10.5%. Since then, the share has been wobbling higher.

- The flow of government funds would just be the first trickle in 2023. The bulk is still coming. 2023’s factory construction will likely near $200 billion.

- This year’s construction spending boom will add to manufacturing’s share of GDP in the future when the plants are up and running.

- Manufacturing has a large-scale impact on the economy, for decades to come, with its secondary and tertiary effects. Construction spending is just the one-time activity to get the building and infrastructure in place.

Canada comparison

For Americans, the reshoring of US factory jobs is as American as apple pie, grits or the NFL (pick your metaphor).

For Canadians, it’s another example of how far we’ve fallen behind our big brother to the south, economically. Whereas the US economy grew by 5.2% in the third quarter, ours contracted by 1.06%. Bank of Montreal economist Doug Porter says despite “the artificial sweetener of rapid population growth” the economy is not growing.

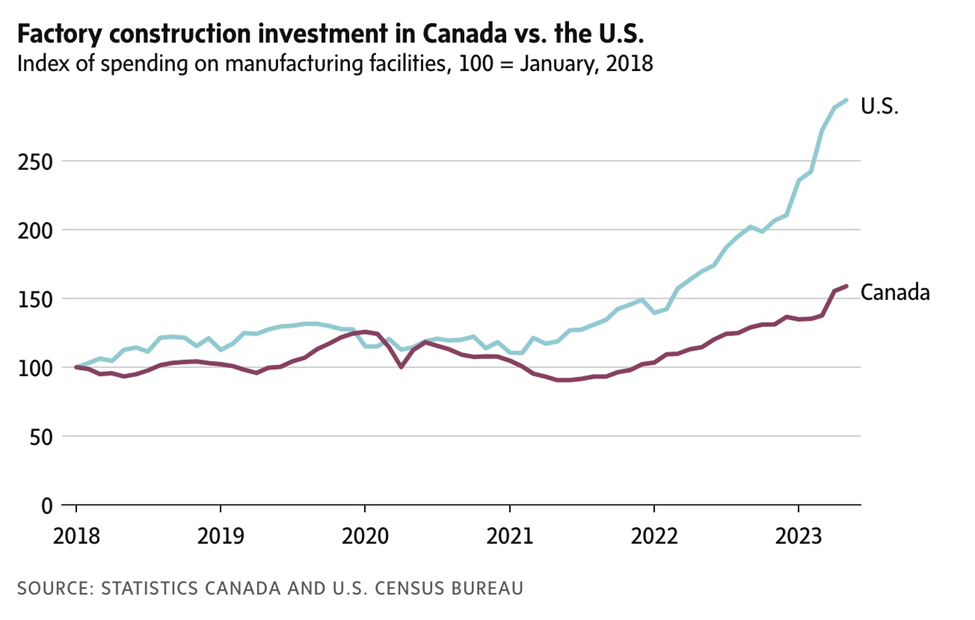

While American manufacturers build factories at a frenzied pace, the Trudeau government’s industrial sector ambitions are decidedly much more modest. The Globe and Mail reported in July that Canadian companies are investing 8.5 per cent less to build manufacturing facilities than they were a decade ago, while real (inflation-adjusted) factory building in the U.S. has nearly doubled since 2021.

The widening gap in factory construction is likely to add to the perennially Canadian fear of investment being lured south of the border, notes the Globe, while admitting that the government has started to take measures to close the gap. This includes $12 billion in tax credits and incentives for cleantech manufacturing, among other measures, in the federal budget, and work on two heavily subsidized electric-vehicle battery plants, one in Quebec and a second in Ontario.

Financial Post columnist Diane Francis goes further in her critique of the federal Liberals’ handling of the economy, taking particular exception to Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland’s boast that “Canada is now a global investment destination of choice … and the IMF projects Canada to likewise see the strongest economic growth in the G7 next year.”

In fact, net foreign direct investment (FDI) plummeted throughout much of the Liberals’ first term, and according to the World Population Review, last year Canada was in eighth place for net FDI inflows, at $54 billion — seven times less than the leading country, the US, at $388B.

Canada lags in several other metrics, too.

The Fraser Institute found prosperity per capita has been stagnant since the mid-2010s, while the IMF suggest Canada’s investment climate has deteriorated compared to other jurisdictions:

“Since 2017, Canada has lost almost all the business tax advantages it previously enjoyed vis-à-vis the United States, a development that undeniably has made the country a less attractive place to deploy capital than it was a decade ago.”

Canada may be attractive and safe, but it’s also expensive, with many residents having a hard time making ends meet. Francis notes that high debts make Canadian businesses, governments and consumers vulnerable to higher interest rates. In 2022, the IMF said Canada’s household debt, loans and debt securities as a proportion of the GDP were the highest in the G7, @107%.

Surprising to no-one, our country also has an excessive price to income ratio, which is the median price paid for property compared to average disposal income. In the middle of this year, Canada’s ratio was 9.6, more than double the US ratio of 4.2, Francis writes.

Conclusion

The reshoring of US manufacturing is a step in the right direction as far as reducing the country’s reliance on foreign supply chains. Billions of dollars in government funding are being directed to computer, electronic and electrical manufacturing. Most of a $1-trillion infrastructure spending bill will be steered towards roads, bridges, public transit, water, and broadband.

How can we marry the need to replace aging infrastructure with reducing our North American dependence on critical metals and base metals like copper and zinc, that are likely to become more expensive in coming years due to supply shortages?

Exposing the copper surplus myth

In building new factories on US and Canadian soil, how can we get the minerals to churn out semiconductors and electric-vehicle batteries?

The answer is to mine them here.

We already know that building new infrastructure has a multiplier effect in terms of the economic activity it creates. A University of Maryland study found that every dollar spent on infrastructure adds up to $3 of GDP growth.

We also know that mining is a big employer. South Africa built an economy around diamond and gold mining. Mining and processing metals like manganese, zinc, rare earths and aluminum could become the lynchpin for a new infrastructure-focused economy.

It’s also the right thing to do — creating local jobs and repairing our decaying cities to boot, making Canada and the US stronger, more independent, and better able to compete internationally.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.