Beetle battle – BC’s last stand

2019.08.01

A warming climate plus decades of mismanagement by various provincial governments threaten to wipe British Columbia’s vast conifer forests off the map.

The destructive force chewing at alarming speed through BC’s majestic stands of lodgepole pine, spruce and Douglas fir, is around the size of a grain of rice. We are talking about the lowly beetle, specifically, the mountain pine beetle and its equally voracious cousins, the spruce beetle, the Douglas-fir beetle, along with another aphid-like tree predator known as the Balsam Woolly Adelgid.

Seemingly powerless on their own, these small bugs breed and feed by the billions. Pine beetles attack groves of old-growth trees, leaving a trail of destruction in their paths. The dead or dying rust-colored pines can be felled for pulp or low-quality lumber if caught in time, before the rot make the wood punky and useless. The dead trees dry and rot ‘on the stump’, providing excellent tinder for forest fires, which are becoming an annual event in British Columbia. Last summer was BC’s worst-ever forest fire season. Previously, the fires would damage a lot of the trees but not kill them. Nowadays, many of the fires burn so hot they destroy the seeds of the burnt-up evergreen trees, scuttling any chance of regeneration.

The costs of the mountain pine beetle, spruce beetle and other infestations are not only environmental, in the loss of timber, carbon sinks and green spaces, but economic. Too many trees killed by mountain pine and spruce beetles have diminished BC’s wood supply, leading to mill closures and job losses across the province.

In this article we’re going deep into British Columbia’s back country, fending off an imaginary swarm of flies and skeeters, to tell the story of what happened to BC’s evergreen forests.

Mountain pine beetle

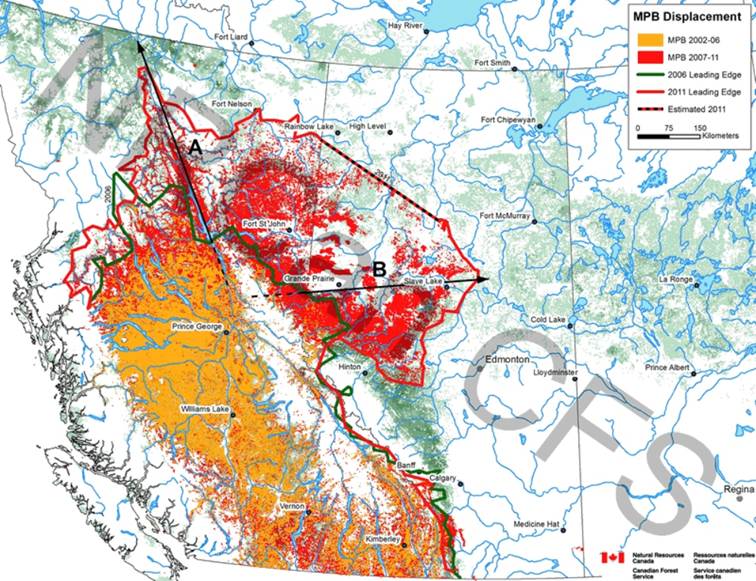

It all started with the mountain pine beetle. The outbreak that began in the early 1990s has affected nearly a third of the 60 million ha of forested land in the province. The BC government estimates that of the 2.3 billion cubic meters of merchantable lodgepole pine, the beetles have destroyed 726 million cubic meters, over a 17.5-million-hectare area.

Efforts to control beetle outbreaks have had very limited success. As of 2017 the mountain pine beetle had migrated well beyond its historic range, into northern BC and eastward into the north-central boreal forests of Alberta.

Science, combined with anecdotal reports from residents, make it pretty well certain that the beetle infestation has resulted from warmer temperatures in the BC Interior, especially during winter months.

Healthy pine trees have a natural defense against insects, a toxic resin. But as more beetles converge on a tree, its defenses become overwhelmed. The pine beetle population was kept under control by relatively cool summers and bitterly cold winters. That all changed with the warming of the planet.

Temperatures in north-central British Columbia used to plunge to -45 degrees C in winter, without the wind chill. Nowadays a cold winter day is -30. For mountain pine beetles, it’s the equivalent of spending the winter in Maui. Entire colonies of the murderous bugs are allowed to flourish.

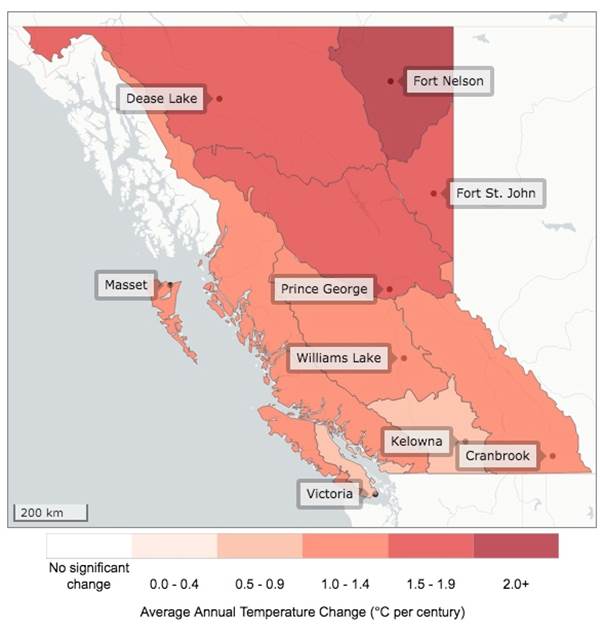

A BC government webpage on climate change reveals some interesting facts. Over the last century (1900-2013) the province has warmed an average of 1.4C. But while southern BC has warmed 0.8C over the last 113 years, in the northern regions, the rate is 1.6 to 2.0C, twice the average global warming of 0.85C.

Moreover, most of that century-long warming trend took place in winter, when the average temperature increase across the province was 2.2C. The farther north you go, the more it has warmed, from 1.5C in southern BC to a toasty 3.8C warmer in the northern-most region of the province.

The way mountain pine beetles attack and infect trees is like something out of a David Cronenberg horror film. Who better to explain it than Mr. Canadian Science himself, Dr. David Suzuki:

How can something so seemingly insignificant cause so much damage? The mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) is a naturally occurring insect that starts its attack when a female uses its senses to find a pine tree (usually lodgepole) that is at least 80 years old. On finding a mature tree, she bores into it while releasing a pheromone that attracts male beetles. When the sex-crazed males arrive, they in turn secrete pheromones that attract more females. The tree mounts a response by secreting a toxic resin that beats back a few beetles. But the beetles have another trick up their sleeves – or in their mouths. They carry spores of a blue-stained fungus, which are released as they bore into the tree. The fungus puts a stop to the spread of resin and allows the beetles to keep tunnelling.

The symbiotic relationship between the beetles and fungus doesn’t end there. The beetles lay eggs under the tree’s bark, and when the larvae hatch, they feed on the blue fungus until they are mature enough to leave the now dead tree, carrying the fungus in their mouths.

Amazing how Mother Nature equipped mountain beetles with such deadly weapons. Combine that naturally-evolved ability with an even greater survivability through warmer winters, and it becomes evident the pine trees never had a chance.

Foxes guarding the hen house

How to topple a forest when it’s nearly down? Put the government onto it. While the pine-beetle epidemic started in the 1990s, it wasn’t until 2001, a decade later, that the province increased its annual allowable cut (AAC), in what would turn out to be a failed attempt to halt the beetle’s progress.

As the climate began noticeably changing, the problem worsened. The warm winters failed to kill the beetles, and due to active fire suppression, mature lodgepole pines, the ideal habitat for mountain pine beetles, proliferated.

Wildfires are a frequent natural occurrence in BC’s forests. They help to renew ecosystems, by heating the wood so hot that the trees release their seeds from cones that are protected by a seal of pitch, or in other species, a thick layer of bark.

Before 1905 the provincial Forest Service allowed fires to occur naturally. Only when they threatened communities or important structures were they actioned. After 1905, annual fire suppression programs interfered with this natural wildfire cycle. According to the BC government, before 1905 fires burned an average of 500,000 hectares, or 1.2 million acres, each year. In recent decades fires only burn an average of 65,000 ha.

That may seem like a good thing, but for stamping out hungry insects, the more forest that burns, the better.

Instead the province’s approach was to implement an aggressive salvage-logging strategy. The objective was to stop the beetle’s spread, then harvest as much dead wood as possible before it either rotted to the point of being worthless, or burned.

The strategy failed. Mass logging clear-cuts across the province did little to stop the infestation from spreading, and in fact it created a host of new problems.

This part requires some political history. Back in 1995, the NDP government of Mike Harcourt introduced the Forest Practices Code which contained a number of rules related to the harvest of forest products. Industry balked at the red tape, so after the BC Liberals under Gordon Campbell were elected in 2001, the province started ramping up the annual allowable cut (AAC) to let companies try and fall the millions of hectares of beetle-kill wood and salvage what they could.

The Liberals replaced the Forest Practices Code with the “results-based” Forest and Range Practices Act. The legislation limited clear-cuts to 60 hectares in the Interior, but there was no limit for clear-cutting forests infested with pine beetles.

In some parts of the province, like Prince George and Quesnel, the AAC shot up by 80%.

The result was to throw sustainable forestry out the window, and leave it up to industry to enforce the watered-down rules.

According to a 2012 story in the Vancouver Sun by the paper’s best environmental reporter, Larry Pynn, among the negative environmental impacts of large-scale salvage logging aimed at eradicating the mountain pine beetle, were:

- Pressuring biodiversity by damaging native plants and funguses, and chasing sway smaller predators like fishers and marten.

- Increasing the risk of flooding and erosion.

- Increasing hunting pressure on both humans and animals due to a proliferation of logging roads.

- Adding to greenhouse gas emissions by removing living trees that act as a carbon sink, and letting dead trees rot and emit CO2.

- Timber companies took with them not only dead pines but other tree species of harvestable value, most importantly spruce and fir.

The province knew about the “significant negative effects” of salvage logging in 2004, Pynn wrote, when Martin Eng, manager of special investigations for the Forest Practices Board, a government watchdog, produced a technical report.

Acting on Eng’s advice, BC’s chief forester Jim Snetsinger recommended to professional foresters that more trees be retained for wildlife – between 10% for cut-blocks smaller than 50 hectares, to 25% for cut-blocks greater than 1,000 ha.

How did they do? A 2009 report also written by Eng found that, on average, timber companies were retaining large-enough islands of trees within the cut-blocks for wildlife, according to Pynn’s article.

But he also found no one was minding the big picture, addressing the collective impact of all those contiguous cut-blocks:

Some of the cut-blocks were recent pine beetle logging, but others dated back three decades to a time before the 1995 Forest Practices Code, when clearcuts did not contain wildlife patches.

Put it all together and you have a significantly altered landscape, multiple patches of logging that were authorized without consideration of the greater overall impact.

More than half of the harvest since 1978 is now in patches larger than 250 hectares and more than one-third in patches larger than 1,000 hectares, the board found.

Incredibly, at least seven harvested patches, amalgams exceeding 10,000 hectares – 25 times the size of Stanley Park – have emerged, the report found.

Eng warned in his 2009 report that the opportunity to reverse the situation “may be lost without quick action.”

Fiber shortage

As mentioned at the top, the fall-out from the pine beetle epidemic has not only been environmental, but economic. The problem boils down to too many sawmills in BC, and not enough timber to feed them all.

Among the casualties are three mills operated by Canfor, including the forestry giant’s Vavenby operation near Clearwater, a small town northeast of Vancouver whose tiny economy, like many in BC, depends on logging and sawmill jobs.

In May Tolko Industries announced the permanent closure of its Quest Wood sawmill in Quesnel, and a reduction from two shifts to one at its Kelowna sawmill. The following month it was Norbord’s turn to herald plans to curtail production indefinitely at 100 Mile House.

Global News quotes a spokesman for Norbord saying the Cariboo region has been under mounting wood supply pressure for the past decade as a result of the mountain pine beetle epidemic, along with some big fires in the area in the summers of 2017 and 2018, that took a lot of timber.

BC government officials are predicting the timber supply will be reduced 20% from about 70 million cubic meters a year to 58 million by 2025.

Adding to the fires and the mountain pine beetle, are high prices for logs and a slowdown in the US housing industry which has crimped demand.

Lumber seller Teal-Jones Group will lay off and reduce the shifts of dozens of contract loggers on Vancouver Island, along with employees at its mill in Surrey, the Financial Post reported in June.

An element of uncertainty has also been tossed into the mix, through new legislation. Bill 22 obliges companies to demonstrate a “public interest” before they can sell or transfer their tree farm licenses on Crown land, to other companies.

A lot of smaller firms that don’t have forest tenures are hoping that Bill 22 frees up some fiber controlled by major companies, so they can run more wood through their mills, but now that is only possible if the large tenure-holders can show that doing so will be in the public interest – a vague requirement.

Spruce beetle

One would think there’s plenty of beetle-kill wood around that could address the timber shortage, but apparently much of that supply has been harvested. It’s gone, and likely, won’t regenerate.

Now a new pest is emerging as a major problem in the low, tree-lined valleys of north-central British Columbia: the spruce beetle.

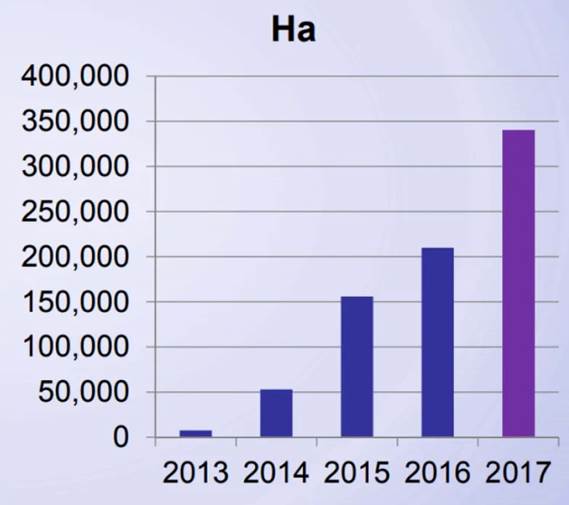

CBC reports aerial surveys have revealed some 340,000 hectares of forest have been impacted. That’s 45 times pre-outbreak levels of 7,653 ha in 2013, and a continuation of a spruce beetle infestation that broke records in 2017.

The current outbreak is centered around Mackenzie, about 200 km north of Prince George.

The spruce beetle’s life cycle is somewhat different from its pine beetle relative. Like the pine beetle, the spruce beetle is thriving with warmer winters, but while the pine beetle likes to bury into old-growth pines, the spruce beetle normally only feeds on fallen or weak trees. According to CBC, only during serious and prolonged infestations, do they become capable of killing healthy trees.

However the fact that the infestation is spreading north, toward the Yukon, west into the Smithers area and east towards the BC-Alberta border, is cause for concern.

A regional forest entomologist interviewed by CBC called the outbreak “larger and more severe than we have seen in the past.” Jeanne Robert explained that the priority is to work with local government and forestry companies, to target the harvest of trees affected by the beetle.

The Bowron model

It’s not clear whether that means clear-cutting vast stands of spruce trees in the same format as the planned eradication of the mountain pine beetle. However anecdotal reports from local loggers indicate a lot of spruce beetle-kill wood is being hauled out from the bush around Summit Lake, the Continental Divide.

Time is of the essence for loggers working with spruce beetle kill timber. While trees killed by mountain pine beetles are still viable 10 to 15 years after death, spruce trees only have about a three to five-year shelf life before their fiber become useless even for making pulp.

The province’s plan to clear-cut beetle-kill forests wasn’t wrong; it was badly implemented, and put into motion far too late, 10 years after BC foresters recognized pine beetles were an epidemic.

We know that clear-cutting done right can be a solution to this problem – exemplified by what was done in the Upper Bowron Valley.

Discolored spruce trees were first noticed by the Forest Service as far back as 1979. A major blowdown in 1974, combined with a series of warm winters, created the perfect conditions for the spruce beetle to thrive on the dead wood. About 175,000 hectares in Bowron Lakes Provincial Park were estimated to be affected.

Like the current spruce beetle infestation, the plan was to target the living timber under beetle attack. Timber licensees in the Upper Bowron were joined by licensees in adjacent areas in order to boost the combined AAC.

The coordinated harvesting operations removed an incredible 15 million cubic meters between 1981 and 1987 – enough timber to build 900,000 1,200-square foot homes!

The operation did come with a price; the clear-cut valley was so large it could be seen from space. However so could the tree plantations, two decades later. A case study of the project notes that, of the 175,000-ha outbreak area, 45,000 ha were replanted, totaling 62.5 million trees. The plantations are 70% interior spruce, 28% lodgepole pine and 2% Douglas-fir.

Douglas-fir bark beetle

The latter tree species is also being victimized by a pest. Loggers north of Prince George right now are cutting bug-killed Douglas-fir trees. The bark beetle has also infested over 90 hectares of forest outside of Nelson.

“We have some really heavily fir-dominated forests [in the Kootenays], especially on our south and west aspects. We’re going to see some pretty devastating effects,” the Nelson Star newspaper quoted Gerald Cordeiro, a forest development manager who first alerted city council to the infestation in October 2017.

A 2018 provincial government report found 78,741 ha were infested by the bark-boring insect. Trees killed by Douglas-fir beetles must be salvaged within just one to two years to remain viable.

Balsam Woolly Adelgid infestation

The last critter we’re going to talk about in this report is the Balsam Woolly Adelgid. The aphid-like pest was first introduced to North America around 1900. Infestations have occurred on balsam fir in New England and Fraser fir in the Appalachian region of the United States, for example.

The adelgid was spotted in the 1990s on Vancouver Island. It somehow migrated to the Coastal mountains and loggers are starting to notice it in north-central BC.

Appearing on bark as white, wooly masses about 1mm long, the adelgid only attacks fir species. A BC government report on them states they can kill a tree after several years of heavy feeding, during which time they inject toxic saliva into their hosts. The microscopic bug has an interesting life cycle:

The adelgid has two to four generations per year. The wingless female can produce in excess of 200 amber colored eggs. The eggs are laid under masses of “cottony tufts” on the underside of branches and on the trunk. Crawlers are visible with the aid of a hand lens beginning around bud break. This stage is the most susceptible to chemical control. There are no males, hence females give rise to more females.

Conclusion

Let’s face it, bugs are cool, except when they’re feasting on your tree farm license or private timber lot. As a province, we now have about 30 years of experience in dealing with these pests which, in BC at least, comprises the mountain pine beetle, the spruce beetle, the Douglas-fir beetle, and the Balsam Woolly Adelgid.

Forest practices dictate there is a right way and a wrong way to deal with an infestation. The wrong way is to delay putting into action a plan to aggressively cut trees attacked by these beetles and an aphid. Three decades on, we’re still fighting the mountain pine beetle. If government officials had listened to the scientists giving them advice, perhaps they would have got on it a lot sooner.

But we have a chance to correct this faulty approach with the other three pests that, when combined with the mountain pine beetle and forest fires, are devastating our conifer forests. The Upper Bowron Valley serves as a template to follow. Clear-cutting can work, if done properly, and with extensive follow-up silviculture.

We need to get it right. Climate change isn’t going away, the winters are getting warmer and our forests, as a consequence, more buggy. Forest fires are here to stay too. Insect eradication is the one variable we have control over, and a lot of science to fall back on.

Look out beetles, we’re coming for ya.

Richard (Rick) Mills

subscribe to my free newsletter

Ahead of the Herd Twitter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether or not you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable but which has not been independently verified. AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness. Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice. AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission. Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage or, in particular, for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

AOTH/Richard Mills is not a registered broker/financial advisor and does not hold any licenses. These are solely personal thoughts and opinions about finance and/or investments – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor. You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments but does suggest consulting your own registered broker/financial advisor with regards to any such transactions

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.