BC’s Golden Triangle is the West’s solution to its copper supply dilemma

2021.11.12

A lot of our recent focus has been on the copper market, and rightly so.

Copper has become one of the main commodities leading the global energy transition. While the metal is a reddish color, its future outlook could not get any “greener” thanks to wave upon wave of surging demand from clean energy applications.

The continued global movement towards electric vehicles is a huge copper driver. EVs use about four times as much copper as regular internal combustion engine vehicles.

Electrification includes not only cars, but trucks, trains, delivery vans, construction equipment, yard tools like lawnmowers, weedwackers and leaf blowers, and two-wheeled vehicles such as e-bikes and motorcycles.

Copper, too, is needed for charging stations and renewable energy, particularly in photovoltaic cells used for solar power, and wind turbines.

Wind and solar systems have the highest copper content of all renewable energy technologies, making the metal important in achieving our climate goals. According to the Copper Alliance, wind turbines require between 2.5 and 6.4 tonnes of copper per megawatt for the generator, cabling and transformers. Photovoltaic solar power systems use approximately 5.5 tonnes of copper per MW.

Of course, copper’s traditional, widespread usage in construction wiring & piping, and electrical transmission lines, makes it a key metal for civil infrastructure renewal.

The base metal is also a component of the global 5G/ broadband buildout. Even though 5G is wireless, its deployment involves a lot more fiber and copper cable to connect equipment located within a building.

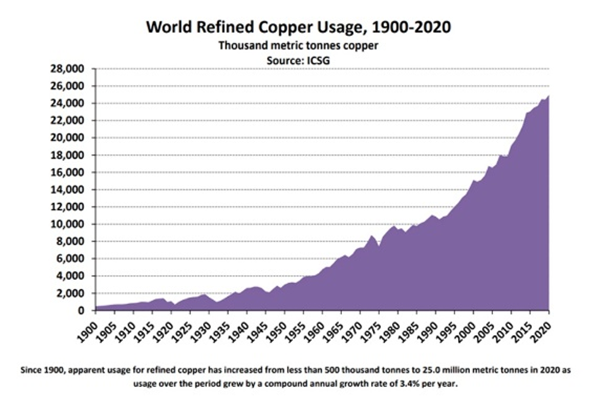

Demand for copper has been growing for decades, and will continue to do so.

According to the US Geological Survey (USGS), copper is already the third-most used industrial metal in the world after iron and aluminum.

Cochilco, the copper commission of leading producer Chile, says global demand for the industrial metal is expected to reach 24 million tonnes this year, up 2.4% compared to 2020, and 24.7 million tonnes in 2022, a 3% increase.

Copper consumption by green energy sectors globally is expected to jump five-fold by 2030, data from consultancy CRU Group shows.

As emphasized during COP26, future copper usage is closely tied to meeting carbon emissions targets.

A report prepared by Wood Mackenzie ahead of the climate change conference emphatically states that the global energy transition starts and ends with metals, with copper sitting at the “nexus” of it all.

In 20 years, BloombergNEF says copper miners need to double the amount of global copper production, just to meet the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles — from the current 20Mt a year to 40Mt.

Along with the climate-related demand driver, copper is also expected to be needed in vast volumes to support the amount of global infrastructure spending either promised or already spent.

Potential impact of BRI

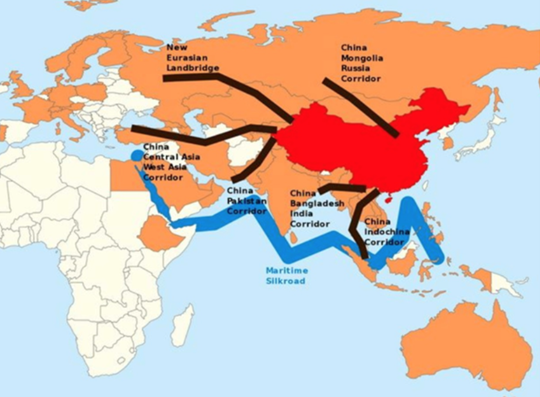

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), first proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2013, is a “belt” of overland corridors and a “road” of shipping lanes. The grand design consists of a network of railways, pipelines, highways and ports that would extend west through the mountainous former Soviet republics and south to Pakistan, India and southeast Asia.

So far over 100 countries have signed onto BRI. According to a Refinitiv database, more than 2,600 projects at a cost of $3.7 trillion were linked to BRI, as of mid-2020.

The Belt and Road Initiative is seen by proponents as an economic driver of proportions never seen before in human history. It would not only allow Asia to relieve its “infrastructure bottleneck” i.e. an $800 billion annual shortfall on infrastructure spending, but bring less-developed neighboring nations into the modern world by providing a growing market of 1.3 billion Chinese consumers.

Opponents argue that is naive and the real intent of BRI is to carve new Chinese spheres of influence in Asia that will replace the United States, in-debt poor nations to China for decades, and restore China to its former imperial glory.

2,600 projects costing $3.7 trillion are linked to BRI, as of mid-2020. Think about how much metal that will entail — in particular, copper, necessary for construction wiring, plumbing and telecommunications, along with renewable energy, 5G and vehicle electrification.

Research commissioned by the International Copper Association, quoted by Mining Technology, found that Belt and Road projects in over 60 Eurasian countries will push the demand for copper to 6.5 million tonnes by 2027, a 22% increase over 2017 levels.

That much copper equates to nearly a third of the 20Mt of copper produced in 2020 — new copper supply that will need to be either mined from existing operations or discovered.

The research also says that, during the first five years of the Belt and Road Initiative, 1.25Mt of copper was used to build a network of power generation and grids, highways and railroads — about 5% of world supply.

Build Back Better World

The Build Back Better World (B3W) initiative is “a values-driven, high-standard, and transparent infrastructure partnership led by major democracies to help narrow the $40+ trillion infrastructure need in the developing world,” according to a June 12 statement from the White House.

Through B3W, the United States and its allies would mobilize private-sector capital in areas such as climate, health and health security, and digital technology.

A statement by a senior official in the Biden administration, quoted in a news article, suggests the bold infrastructure plan is a rebuke against China’s growing assertiveness and economic/ military rise over the past 40 years:

“This is not just about confronting or taking on China. But until now we haven’t offered a positive alternative that reflects our values, our standards and our way of doing business.”

Build Back Better US

In the United States, the seeds of copper demand is planted in the hundreds of billions of new spending outlined in the Build Back Better framework and in President Biden’s “bipartisan” infrastructure bill.

The bill calls for investing $40B for bridge repair, replacement and rehabilitation — the largest investment in bridges since the construction of the interstate highway system; $39B to modernize public transit; $66B for passenger and freight rail; and $12B in partnership grants for intercity rail service including high-speed rail.

Vehicle electrification is a major part of the legislation’s focus. It would provide $7.5B for low-emissions buses and ferries, and aims to deliver thousands of electric school buses to districts across the country. Another $7.5B would go towards building a nationwide network of plug-in EV chargers.

This past August, Biden signed an executive order requiring that half of all US new vehicle sales be electric by 2030.

$65 billion is earmarked for rebuilding the electrical grid including thousands of new miles of power lines and expanding renewable energy, according to the White House.

Biden’s proposed beefing up of the electric vehicle sector with subsidies, adding 500,000 new charging stations, and converting half a million school buses to zero emissions, would require nearly 2 million tonnes of copper over the next 10 years, or 200,000 tonnes a year, states a 2021 report from Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ), via Kitco.

That is equivalent to adding 10% to US copper demand of 1.9 million tonnes, or 1% to global demand. Aluminum and nickel also are expected to benefit from EV sales.

“The real kicker will be the $7.5 billion investment in electronic vehicle (EV) infrastructure. Overall we see growth in copper demand hitting double digits over the next year or two,” ANZ wrote in the report.

The Biden administration has set a goal to have 100% carbon pollution-free electricity by 2035, then carbon neutrality by 2050. The US climate plan would require electric vehicles to make up at least half of the nation’s new auto sales by 2030.

“Construction has traditionally been the biggest contributor to demand for most metals,” the report emphasized. “Therefore, this spending package should boost demand for copper and zinc, in particular.”

ANZ points to wiring and cabling in new home construction as an example of higher expected copper usage.

“Building and construction use 22–23% of U.S. copper demand, which is nearly 800kt of copper,” the report specified. “Construction of two million houses would generate nearly 320kt of copper demand over eight years, 40kt per year in a very optimistic scenario.”

Copper crunch

While healthy demand is the hallmark of a commodity bull market, the real driving force, according to those in the industry, is the availability and reliability of supply.

The challenge for mining companies will be finding enough metal to meet the demand because the hurtling freight train of copper demand is about to slam into the immovable object of a supply crunch.

Roskill forecasts total global copper consumption will exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization and electricity demand. Total world copper mine production in 2020 was only 20Mt.

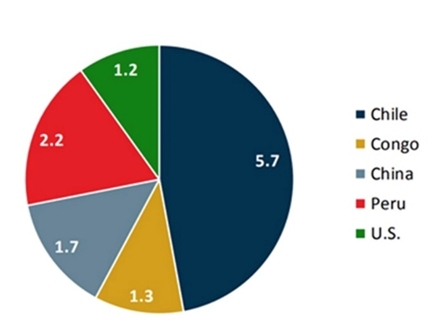

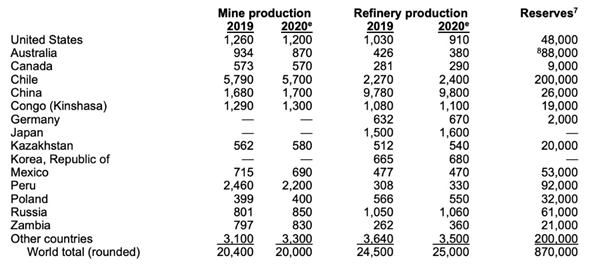

Source: USGS

According to a 2021 report from Wood Mackenzie, mining companies will need to spend $1.7 trillion over the next 15 years, to supply enough copper, lithium, graphite, cobalt and nickel for the shift to a low-carbon world.

The commodities consultancy says meeting new emissions targets being set by countries like Canada, the US, Britain, China and Japan, will mean large-scale deployment of electric vehicles, renewable power and electrical transmission, all of which will require copious metal content.

At least 19 million tonnes of additional mined copper per year will be needed to limit global warming to 2C on pre-industrial levels by the end of the century, a scenario that aligns with 2015 Paris climate accord targets.

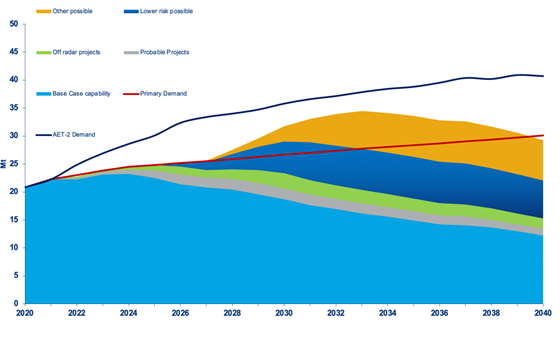

Under such a scenario, global demand for primary copper is expected to grow by 3.5% per annum, leading to a doubling of demand by 2040 (see graph below).

Even a base-case energy transition outlook, which limits global warming to 2.5C, requires nearly half as much, about 9 million tonnes, at an annual demand growth of 2%.

Based on Woodmac’s calculation, it is estimated that the capex for base metals mining projects needs to quadruple to about $2 trillion, to achieve an accelerated energy transition.

The report says: “The supply gap represented by the uncommitted proportion of the potential 2030 market represents a major opportunity for investment, with the associated tonnages being truly transformational when set in the context of current market size.”

Remember, the 19-million-tonne gap almost matches the whole year’s mine supply in 2020. This implies a new Escondida mine (~1 million tonnes production) must be discovered and enter production every year for the next 20 years!

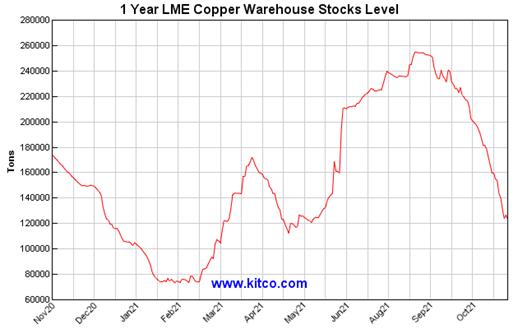

Earlier in the year commodity strategists at Bank of America expressed their concerns about the world “running out of copper” amid growing demand for the metal. At the time, copper inventories were sitting at their lowest in 15 years, enough to cover just 3.3 weeks of demand.

Low pipeline

The question whether or not the large copper producers can deliver on their plans is being asked at a critical juncture.

Without new capital investments, Commodities Research Unit (CRU) estimates that global copper mine production will drop from the current 20 million tonnes to below 12 million tonnes by 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15 million tonnes.

Over 200 copper mines are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place, CRU says.

As things stand, the global copper discovery cupboard is bare.

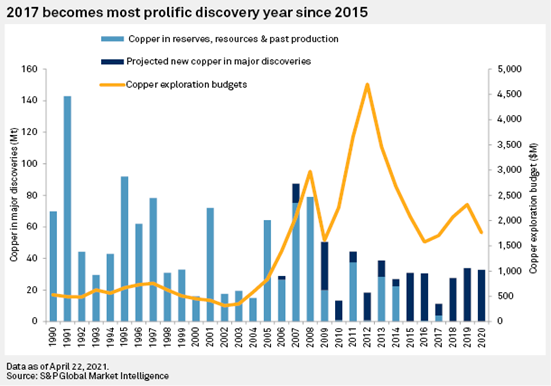

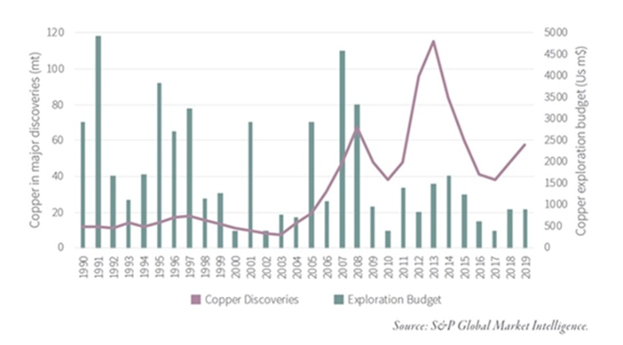

S&P Global Market Intelligence estimates that new copper discoveries averaged nearly 50 million tonnes annually between 1990 and 2010, but since then, discoveries have fallen by 80% to only 8 million tonnes per year.

According to resource investment house Goehring & Rozencwajg, the number of new world-class discoveries coming online this decade “will decline substantially” and depletion problems at existing mines will accelerate.

Also, geological constraints surrounding copper porphyry deposits, a subject few analysts and investors understand, will contribute to the problems, their report said.

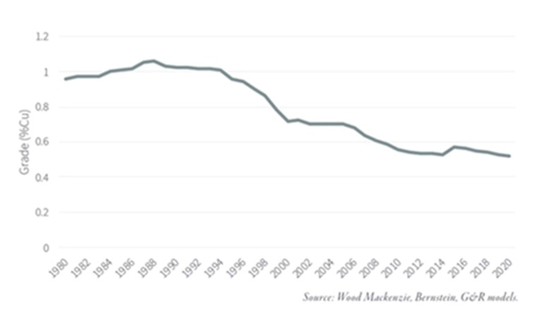

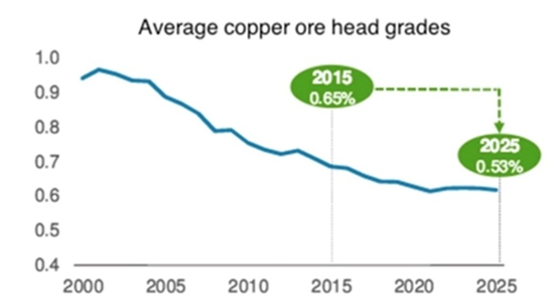

By 2015, the industry’s head grade was already 30% lower than in 2001, and the capital cost per tonne of annual production had surged four-fold during that time — both classic signs of depletion. The average mined copper grade is now just 0.62%.

As the higher-grade portions of deposits are mined out (known in industry jargon as “high-grading”), operators must process lower-grade ore, resulting in a decline in production unless capital is deployed to process more ore to maintain output.

This trend is likely to continue, according to Goehring & Rozencwajg, predicting that greenfield and brownfield reserve additions are expected to disappoint through the decade.

On top of depletion, lower grades, high-grading, and a dearth of new copper discoveries, there are other issues making it difficult to add to supply.

One problem is the need to go further afield and dig deeper to find copper at the grades needed to economically produce copper products for end users. This usually means riskier jurisdictions that are often ruled by shaky governments with an itchy trigger finger on the resource nationalism button. All the low-hanging copper “fruit” has been picked. Combine that with production problems and you have the makings of a supply shortage.

The current copper pipeline is the lowest it has been in a century. After First Quantum delivered the first copper from Cobre Panama (285-310,000t per year) in 2019, BMO does not see the next batch of +200,000-tonnes projects until 2022-23 — “when the likes of Kamoa (501,000t per year), Oyu Tolgoi Phase 2, and QB2 (316,000t per year) are likely to offer meaningful supply growth.”

New copper supply is concentrated in just five mines — Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC. (the first phase of Ivanhoe’s Congolese mine reached commercial production in August of this year)

An AOTH analysis showed that in four of the five mines where new copper supply is concentrated, there are offtake agreements either in place or implied, with non-Western buyers. In the case of Kamoa-Kakula, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project. Nearly half of Cobre Panama’s annual production goes to a Korean smelter under a 2017 offtake agreement. Escondida and Quebrada Blanca are both partially owned by Japanese companies — one can make the assumption that a corresponding percentage of production will be going there.

We can hardly call this situation Western security of supply, when most of the raw copper material (cathodes or concentrate) is going to China, South Korea and Japan, who then turn around and sell more expensive copper end products to North America and Europe.

We’re becoming short of copper in the West and there’s no two ways about it. We weren’t paying attention when China cornered the rare earths market back in 2010, and we were also blind to the Chinese locking up global supplies & processing capabilities for nickel, cobalt, graphite and lithium.

The Biden administration is moving to ban mining in the Boundary Waters area of Minnesota, is trying to permanently protect Bristol Bay, effectively killing the huge Pebble copper-gold project in Alaska, and the Democrat-controlled Congress wants to impose an 8% gross royalty on existing mines and 4% on new ones. A House committee is also attempting to block Rio Tinto from building its Resolution copper mine in Arizona.

Canada’s weak politicians preferred to export raw materials, mostly to China, meanwhile the US and EU went all “NIMBY.”

Then you look at what’s happening in four of the world’s largest copper-producing countries, Chile, Peru, Zambia and the DRC, all of which are rising threats for resource nationalism, making the required ramp-up in copper production to meet expected demand from electrification/ decarbonization all that much harder, if not impossible.

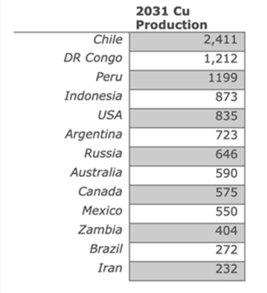

The other countries on the CRU’s list of countries from which 2031 copper production is anticipated, (see table below) are no more friendly to Western interests.

We are talking about Russia and Iran, both subject to US sanctions, Mexico whose nationalist government is the most likely among Latin American countries to expropriate mines or hit them with higher taxes, and Indonesia which already has a template for local ore beneficiation. Also, the Indonesian government owns Grasberg, the world’s second largest copper mine, finally wresting it from Freeport McMoran and Rio Tinto after many years of conflicts over ownership.

None of these issues are going to be fixed in a decade, in fact there is every chance they will get worse, especially given that we have to consider the impacts of climate change on future copper production.

Where will new copper supply come from?

All is not lost, however, if we consider that the mining industry is on the hunt for large deposits that have favorable grades and are in locations amenable to mine developments.

BHP’s decision this year to shift its exploration headquarters to Toronto fits with statements made by Canadian officials who are talking up Canada as a hub for clean-tech metals.

“Canada offers renewably generated electricity, a skilled workforce, a stable and predictable jurisdiction to operate in, the rule of law – a commodity very much in demand these days – and an abundance of the critical minerals needed for the batteries that power electric vehicles,” said Francois-Philippe Champagne, the federal Minister of Innovation, Science, and Industry, at this year’s PDAC mining conference.

Since I have been to the area several times, know the potential, and live within a days drive AOTH set out to investigate BC’s Golden Triangle to see what might be available for future copper supply. And if a BC copper smelter/hydromet complex to process the area’s ore is justified.

Spoiler alert: we will come to the conclusion that the Golden Triangle district of northwestern British Columbia is an excellent place to shore up new copper supply and to build smelting and refining capacity.

Copper-gold porphyries in the GT

“53 per cent of the exploration spending in B.C. in 2020 went to the northwest of the province, home of the Golden Triangle exploration and mining district around Stewart B.C.” Gordon Clarke, director of the B.C. Mineral Development office

“The great mineral endowment of the Iskut district is due to its location along intersecting sets of long lived deep crustal lineaments that provided conduits for magmas and fluids during a succession of tectonic regimes… Such lineaments provide ideally fertile ground and permeability conditions that can, and do, result in near-superposition of vastly different mineral deposit types.” JoAnne Nelson, Emeritus Scientist with the British Columbia Geological Survey (BCGS)

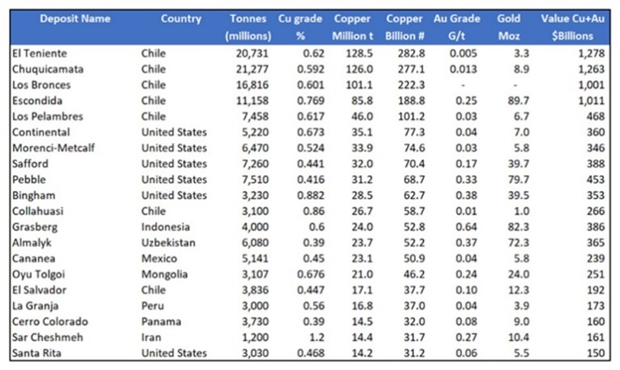

In 2008 the US Geological Survey compiled a list of porphyry deposits around the world, which are ranked in the table below.

Major porphyry camps and porphyry-related gold deposits within the Golden Triangle include: Schaft Creek, Galore Creek, the Red Chris-GJ-North Rok-Tatogga cluster and the KSM-Brucejack and Snip Bronson camps.

Chief among the GT’s deposits/ camps is the giant Kerr-Sulphurets-Mitchell (KSM) deposit being developed by Seabridge Mining. This deposit is not on the above list, but it deserves to be.

The copper-gold-silver porphyry, and its estimated mineral content, is spectacular — Sulphurets’ 199 million ounces of gold and 790Moz of silver makes the KSM project, being advanced by Seabridge Gold, the largest undeveloped gold deposit in the world. It also has 51 billion pounds of contained copper.

In fact, based strictly on its copper content, Sulphurets would rank 14th on the USGS list; if its gold value is counted, Sulphurets would be number 5.

Nobody therefore can argue that Sulphurets doesn’t rank as among the monster porphyry gold systems in the world.

Interesting fact: The Sulphurets Hydrothermal System is effectively the porphyry system that generated KSM, Ironcap, Treaty Creek and Brucejack.

The current resources of KSM, Treaty, Snowfield and Brucejack are: 199Moz gold, 730Moz silver and 51B pounds Cu in a 20 km circle representing one of the greatest concentrations of metal value on the planet.

But the Sulphurets Hydrothermal System is just one of many hydrothermal systems in the Golden Triangle.

Porphyry copper-gold deposit Galore Creek, explored in the 1960s and 70s, now owned jointly by Newmont (TSX:NGT) and Teck Resources (TSX-B:TECK), has 9 billion pounds of copper, 8 million gold ounces and 136 million ounces of silver.

Another porphyry, Schaft Creek, a JV between Copper Fox Metals (TSXV:CUU) and Teck, contains 7.7 billion pounds of copper, 6.9 million ounces of gold, 511 million pounds of molybdenum and 54.2 million ounces of silver. (2021 mineral resource estimate)

Red Chris had reserves of over 300 million tonnes grading 0.359% copper and 0.274 g/t gold, plus additional low-grade silver, however, the known resources outside the open pit model are ten times that amount. First run by Imperial Metals, then 70%-purchased by Australia’s Newcrest in 2019, this $700 million gold and copper mine entered production in 2015 and is expected to go until 2043.

According to Imperial Metals, in 2019 the open pit mine produced 71.9 million pounds of copper, 36,471 oz of gold and 133,879 oz of silver.

In March of this year, Newmont struck a deal with GT Gold to take over the junior and its Tatogga gold-copper discovery in the Golden Triangle. Tatogga is located about 14 km west of Red Chris and includes the primary Saddle North asset.

Canadian copper production

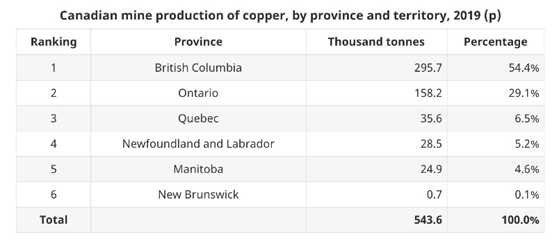

Canada mined just 570,000 tonnes of copper last year, and smelted only 290,000t, compared to global production of 20 million tonnes.

British Columbia, in 2019, produced over half the nation’s copper (54%), compared to 29% in Ontario and just 6.5% in Quebec. The only copper processing facilities in Canada are the Horne smelter located in Rouyn-Noranda, Quebec, and the CCR refinery in Montreal.

All the copper mined from British Columbian operations is shipped to Asia.

CESL Process

While there has been talk of building a refinery in BC for decades, so far the political will hasn’t been there. The smelter’s ore feed could not only be derived from KSM, but all of the neighboring deposits, including Red Chris, Schaft Creek, Galore Creek, Newmont’s Tatogga, and no doubt from the many deposits waiting to be discovered. Elsewhere in BC Tech’s partially owned Highland Valley, Gibralter and Copper Mtn could potentially supply feedstock for a BC copper smelter/hydromet. And the Yukon has a lot of copper, Carmacks and Casino for example.

The key to this plan, wild as it may seem, is the smelter must have the ability to process copper and gold. Well it just so happens that Teck Resources, part-owner of Highland Valley, Galore Creek and Schaft Creek, has the technology to do it.

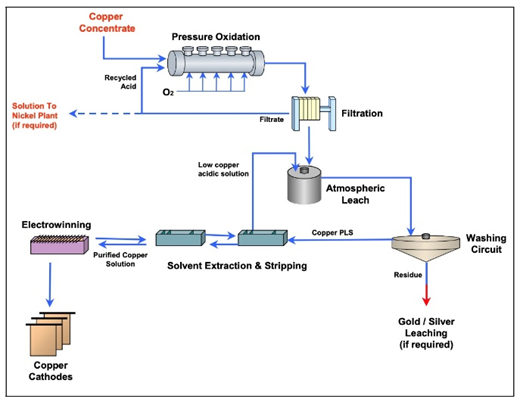

Cominco Engineering Services (CESL), a subsidiary of then-Teck Cominco Metals, began developing the CESL Process in 1992, as an alternative to conventional smelting and refining of copper concentrates for the production of LME Grade A copper cathode.

The proprietary hydrometallurgical processes are for the treatment of nickel, copper and copper-gold concentrates. According to a technical paper, Besides successfully treating standard concentrates, the processes have a demonstrated capability to refine “dirty” concentrates containing fluoride, arsenic, bismuth and other impurity elements that pose serious challenges in conventional smelting.

The first commercial facility constructed using CESL technology was built by Vale in the Carajas region of Brazil. The 10,000 tonne per year CESL copper plant was reportedly intended to be a prototype, supporting construction of a much larger plant to process nearby concentrates from future Vale projects.

The plant was successfully able to meet all objectives including training personnel in the region and demonstrating the technology on a commercial scale, according to Teck:

In 2002 through 2005, pilot-scale test work conducted by CESL indicated that gold was recoverable through cyanidation of the copper plant residue. Preliminary results have shown exceptional gold extraction and minimal cyanide consumption.

The CESL Process involves oxidation of sulphide concentrates at elevated pressure and temperature in the presence of catalytic chloride ions, within an autoclave. The oxidized copper forms basic copper sulfate (BCS). Copper from the BCS is subsequently leached under mildly acidic conditions at atmospheric pressure and temperature. Copper is recovered from solution by conventional solvent extraction and electrowinning.

Conclusion

“The Golden Triangle has a world-class metal endowment. It has 220 million ounces of gold and 93 billion pounds of copper and very significant silver and molybdenum. Combined, they represent a total potential value of US$0.7 trillion. Only three per cent has actually been mined.” Bram van Straaten, senior minerals geologist, BCGS, February 2021.

If Teck’s CESL Process was brought to somewhere in the Golden Triangle, seemingly the ideal location for a new refinery, considering all the copper-gold deposits grouped so closely together, it could prove to be just what the area needs, i.e., the key to unlocking the huge mining potential of the Triangle which up until now, has stayed locked within the area’s vast copper-gold porphyries and epithermal gold deposits.

A shared refinery would lower each project’s transportation costs and make the economics workable even if copper and gold prices were to fall, which seems unlikely given current market conditions.

Although we envision the world’s copper majors supporting a refinery, in a kind of “build it they will come” scenario (some are already there, including Teck, Newmont and Newcrest), we don’t see this happening without government backing. Refineries cost hundreds of millions, and no company is likely to take it on, alone, or even through a partnership.

Consider: while it is usually better for governments to stay out of the way of markets, there are cases when pushing industry in a certain direction can make a difference.

An example is what happened when Robert Friedland’s Diamond Fields sold its Voisey’s Bay nickel discovery to Inco, then the world’s largest nickel producer, for $4.3 billion.

If Inco wanted to extract minerals in Newfoundland, the provincial government maintained that they had to build a processing plant. As a result of negotiations, hundreds of millions of dollars in research funding went into the development of “hydromet” (hydrometallurgy) mineral processing technology to replace the normal smelting process. Hydromet is better for the environment and gets better recoveries.

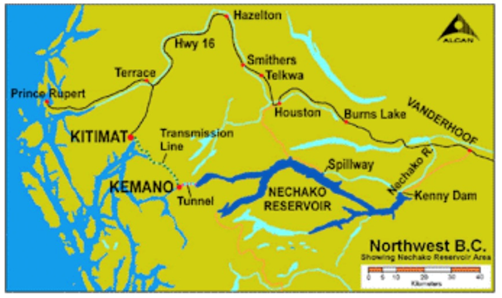

And it’s not like there hasn’t been a precedent set in British Columbia. In the 1940’s, the government wanted to develop BC’s considerable natural resources particularly in the sparsely populated northwest and northcentral regions. A survey of the hydroelectric power potential, done in the 1920’s, identified the Nechako watershed, a vast river and lake system draining 14,000 square kilometers of northcentral BC.

Aluminum producer Alcan was invited by the government to investigate the concept of developing an aluminum industry in the area.

The resulting Kitimat-Kemano project in its day was the largest privately funded construction undertaking in Canada. It cost $500 million in 1950 dollars, or more than $3.3 billion in today’s currency.

Some remarkable engineering feats were achieved, including: building the largest rockfill dam in the world at the time; constructing the Kenney Dam 193 km east of the Nechako reservoir; completing an 82-km power transmission line from the former town of Kemano to Kitimat, built at an elevation of 1,500m through rugged mountain territory; and boring 16 kilometers through coastal mountains to complete a water intake tunnel as wide as a two-lane highway, to carry river water to the twin penstocks of the Kemano powerhouse, where it tumbles 800 meters, nearly 16 times the height of Niagara Falls, to drive the generator turbines.

Located 75 km southeast of Kitimat, the Kemano Generating Station was completed in 1954, providing hydroelectricity for Alcan’s Kitimat aluminum smelter. The cathedral-shaped powerhouse, drilled and blasted 427m inside the granite base of Mt. DuBose, produces 896 megawatts of power from its eight generator units, making it the largest power producer in the province when it was built in the early 1950’s. Even today, the 67-year-old facility is the biggest high-pressure hydropower generation facility in North America.

A 2016 upgrade involved a $6 billion investment to upgrade the smelter, using technology to lower its carbon footprint and make the smelting process more efficient and cost-competitive. In 2017 Rio Tinto approved $600 million for a second tunnel. Construction is underway, with a news release this week stating that the tunnel boring machine has broken through to complete the excavation stage of Kemano T2, designed to divert water to the Kemano powerhouse.

Back on point, it is our opinion that, with the Golden Triangle’s exceedingly rich mineral endowment — an estimated 188 million ounces of gold reserves (47.7Moz proven and probable), 1.2 billion ounces of silver (214Moz P&P) and 55 billion pounds of copper (10B lbs. P&P) — along with updated road and power infrastructure, receding glaciers, new geological theories and good relationships between mining/ exploration companies and First Nations, these are all good reasons for building a new smelter in northwestern BC to chemically separate copper, gold, silver and other metals using Teck’s CESL Process.

We don’t have to follow the lead of the United States and become like the anti-mining Biden administration, through preventing large projects like Pebble and Resolution from being developed, and legislating royalty fee increases that discourage mining and mineral exploration.

Instead, we could choose to get ahead of the West’s insecurity of copper supply, i.e., not having enough copper to handle the oncoming crush of demand, due to electrification & decarbonization, by proactively developing our resources, and becoming a secure Western supplier. Right here in BC, in the Golden Triangle.

Canada only has one copper smelter and one refinery, in Quebec. The richness of BC’s Golden Triangle mineral endowment justifies at least one smelter/ hydromet. British Columbia has the minerals, the roads, the power and deep seaport infrastructure, the processing technology and the expertise. All we need is the political will.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.