BC burning

2022.09.09

Whether or not you believe global warming is human-caused or the result of the Earth’s natural warming and cooling cycles (we at AOTH lean towards the latter), there is no denying that climate change is happening all around us, and a lot quicker than most had expected.

Since the 1990s, the number of weather-related disasters around the world has doubled. Examples include forest fires, flooding, aquifer depletion, sea rise, saltwater intrusion, atmospheric rivers, heat domes, hurricanes, severe snow storms and deep freezes.

Although Western Canada experienced an unusually cold and wet spring, delaying the start of summer until the beginning of July, Mother Nature is making up for it with a last blast of heat that could keep the forest fires burning well into the fall.

And as we saw last November with the “atmospheric rivers” that brought catastrophic flooding to southern British Columbia, our problems don’t end with the extinction of the fires.

Between wildfires, landslides from melting glaciers, flooding, and freak winter storms resulting from a breakdown of the northern polar vortex, a witch’s brew of bad weather, at least partially induced by climate change, is awaiting the province as British Columbians settle back into the familiar routine of school and work.

Some like it hot

Let’s begin with how hot it was this summer, locally and nation-wide.

Global News reported on Friday, Sept. 2 that August 2022 was the warmest ever in BC, and the province’s second-hottest month, based on temperatures taken at Vancouver Airport.

The average temperature in August, 20.3 Celsius, just missed the record-breaking monthly average of 20.6 C, set in July, 1958.

But if you thought the summer of 2022 wasn’t as scorching as last summer, you’d be right. According to Global, from June to August this year, a mean temperature of 18.3 C was recorded, which, while above the 17.2 average, makes the summer of 2022 only the sixth hottest on record, compared to 2021, the second-hottest June to August.

Fort St. John, Abbotsford, Kelowna, Vernon and Penticton all recorded their hottest Augusts, with dozens of regions across the province breaking daily high temperatures in both July and August.

As BC sizzled, other parts of Canada also basked in the heat.

Looking back on meterological summer, which runs from June 1 through Aug. 31, the Weather Network reports almost all of the country except northern Ontario saw above-seasonal temperatures, in the range of 0.5 to 1.5 degrees warmer.

Among the surprising hot spots, St. John’s, Newfoundland was 2.3 degrees warmer than normal, and Charlottetown, PEI shattered its summer heat record with average temps 1.2 above seasonal. One former Newfoundlander now living in BC, who went home for July, said people were sitting outside in shorts and shirt sleeves, in a town where summer evenings are normally brisk, requiring pants and a pullover.

The Weather Network says all of the Atlantic provinces ran particularly hot compared to the rest of the country.

Northern Canada too was unusually balmy. Temperatures across the Northwest Territories and Nunavut were quite a bit above seasonal. The small community of Rankin Inlet recorded its warmest ever summer, with average temperatures just shy of 2 C above normal.

The Arctic is warming two to three times faster than anywhere else on the planet, driven mostly by disappearing sea ice. Open water absorbs up to 90% of the sun’s radiation, raising ocean water temperatures and creating a feedback loop that causes even more melting. Read more

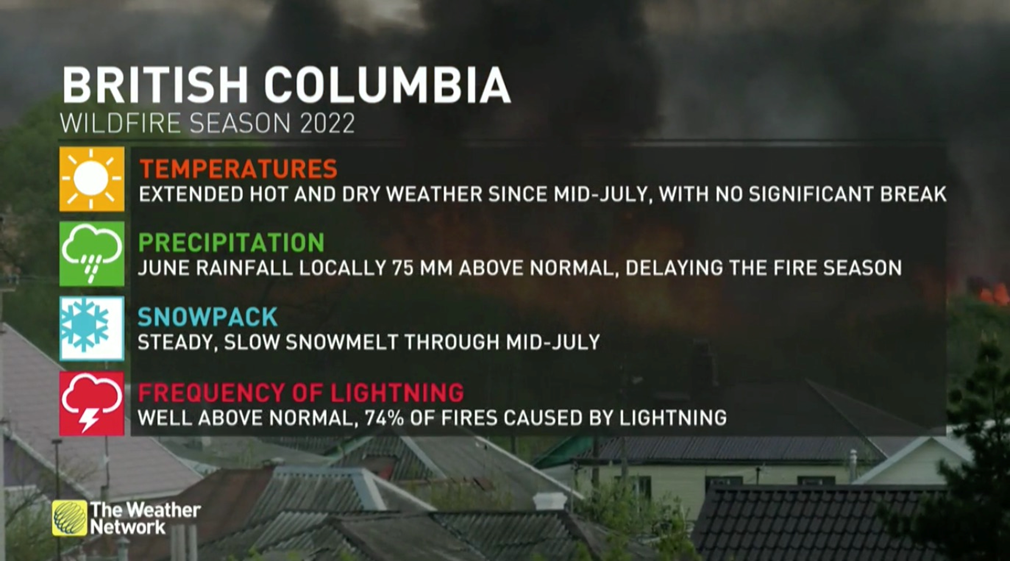

Fires

Back to BC, August was not only hot, it was extremely dry.

The six weeks from mid-July to end of August saw only 3.6 millimeters of rainfall, when typical average rainfall is 36.7 mm. Some areas of BC have been declared Level 3 due to hot and dry conditions, on a drought scale with five being the most severe.

That, of course, creates the ideal conditions for wildfires, either human-caused or the result of lightning strikes. As of Thursday, Sept. 8, there were 188 active fires burning in BC, with 12 sparked in the last two days.

In Hudson’s, Hope, located in the northeast Peace River region, children were prevented from attending the first day of school, Tuesday, due to the Battleship Mountain wildfire. The blaze is still burning over a 100-square-km area, equivalent to the size of Vancouver.

The municipality declared a state of emergency and issued evacuation orders for the western part of the district. As of Sept. 6, the fire burning 50 km west of Hudson Hope had about 48 firefighters and six structure protection personnel working on it.

Elsewhere in northeastern BC, the Weather Network reports the Bearhole Lake fire near Tumbler Ridge was still burning out of control Tuesday, and DriveBC says Highway 52 is closed between Kelly Lake Road and Stone Creek Road until further notice. The Peace River Regional District upgraded an evacuation alert to an evacuation order Sunday evening for the community of Kelly Lake.

In southwest B.C., the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District downgraded an evacuation orde issued Saturday to an evacuation alert for five district lots and several recreation sites and trails in the Lillooet area, near the Downton Creek fire.

Further east, smoke advisories issued by Environment Canada due to fires burning locally and south of the border were lifted, but a portion of E.C. Manning Provincial Park south of Highway 3 remains on evacuation order.

Two fires are burning in the park — the Fat Dog Creek fire north of the highway, and the Heather Lake fire, which originated in the U.S.

Earlier this week the Heather Lake fire jumped the US border and the Canadian portion quickly grew to 2,100 hectares, as of Wednesday night, due to the amount of dry fuel in the area. Dozens of residents nearby whose homes are threatened, were placed on evacuation alert.

So far the province has had over 1,400 fires, less than the +1,600 last year which made 2021 the third worst forest fire season on record, but still a significant number.

“Wildfire activity has increased significantly to begin the month of September, not only here in B.C., but also south of the border, particularly in Washington state,” said Jessie Uppal, a meteorologist at The Weather Network.

There are currently three large wildfires burning between Seattle and Spokane, causing smoke to drift over the border into southern British Columbia and southern Alberta. The smoke is so widespread, it can be seen from space with satellite imagery.

The fire data contains one bright spot: a record-low number of human-induced fires. According to the BC Wildfire Service, just over 20% of this year’s wildfires can be traced back to people, such as un-extinguished cigarette butts and campfires, with the rest caused by lightning. The good news doesn’t carry over to next-door Alberta, where people have been responsible for about half of all fire starts this year. The bulk of Alberta’s fires have been in the Fort McMurray area, where more than 100 fires have consumed over 100,000 hectares.

An anomaly is the Chetamon Mountain wildfire located in Jasper National Park, on the BC-Alberta border. The fire broke out on Sept. 1 during a lightning storm and quickly tripled in size to more than 1,500 hectares. On Sunday night the fire ignited some transmission poles, cutting power to the town and nearby campsites.

The Weather Network warns that warm temperatures expected throughout September will heighten the risk of wildfire activity.

Landslides

While hot and cold temperatures are felt by everyone, everywhere, sometimes weather and climate-related events happen far from civilization; it’s similar to the meme, “If a tree falls in a forest, and nobody is there to see it, does it make a sound?” (of course it does)

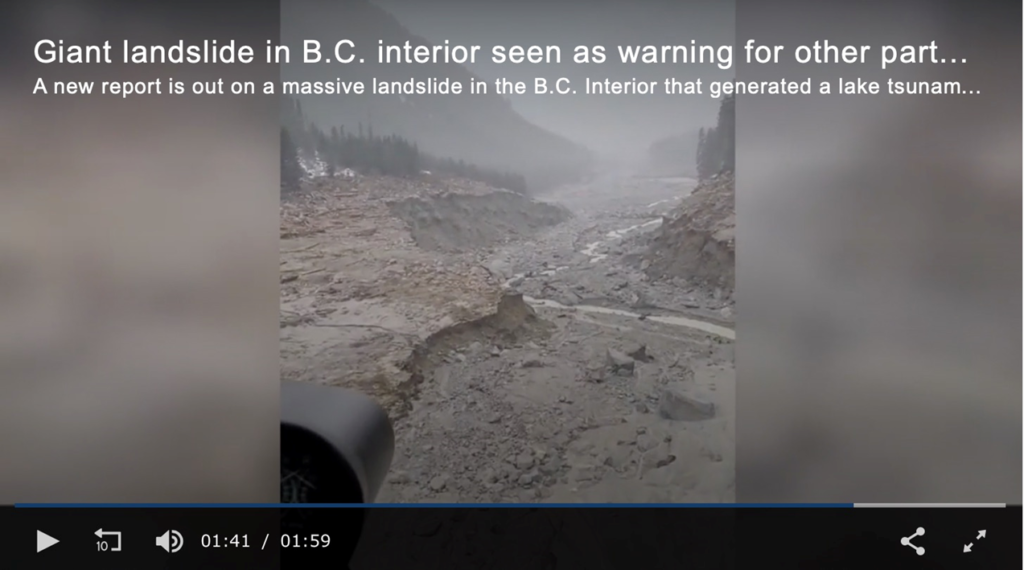

On Nov. 28, 2020, a landslide in a remote British Columbia valley sent 18 million cubic meters of rock hurtling down the side of a mountain.

The slide at Bute Inlet, about 160 km from Vancouver, was so large, when it hit Elliot Creek, it caused a 100-meter-high tsunami that wiped out 10 kilometers of salmon habitat and was detected as far away as Germany, Japan and Australia.

“Imagine a landslide with a mass equal to all of the automobiles in Canada travelling with a velocity of about 140 kilometres an hour when it runs into a large lake,” Marten Geertsema, lead author of a study on the slide, and adjunct professor at the University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC), described it in an interview with Global News.

While it’s impossible to say precisely what caused the slide, scientists know that glaciers, which once blanketed and held the slopes together, are melting rapidly due to climate change, leaving the sides of the mountains loose and exposed. A rainstorm or unusually wet conditions can become the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

The incident serves as a warning to other parts of BC. Glaciers in central BC are melting faster than almost anywhere else in the world. According to a study published earlier this year by geologists at UNBC, the rate of glacial retreat between 2010 and 2020 was seven times faster than between 1984 and 2010. Smaller glaciers on Vancouver Island are disappearing 32 times faster, in the same period.

As glaciers melt, they leave unstable rock literally hanging in the air. In a video, Global News reporter Ted Chernecki says that scientists are now looking closer at all melting glaciers, especially those with shoreline communities within striking distance of the next tsunami.

The crack of a glacier breaking apart was the trigger for the Mount Meager landslide near Squamish. Researchers think that warming temperatures are responsible for the “fumaroles” atop Mount Meager emitting hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide and steam. They are studying the gases, the expansion of the fumoles, and how fast the ice is shrinking, which could trigger an eruption and a landslide like in 2010, only 10 times worse.

Glacial melt

Over the last few decades, almost all the world’s glaciers have shrunk and the rate of decline is accelerating. An expert on glacier dynamics, associate professor Jeff Kavanaugh at the University of Alberta, expects that between 60 and 80% of the ice volume in BC and Alberta will be lost by 2100.

The phenomenon has the potential to cause both water shortages and flooding.

Of course, the main factor driving glacial melt is rising temperatures. A rise of 1.5 C is considered to be the tipping point, beyond which further warming is expected to have disastrous economic, political and environmental consequences. We are already at 1.1C; arguably there is no stopping it. The Earth will warm until it starts cooling. The proof is in the geologic record. All we can do is try to manage the effects as best we can.

Kavanaugh estimated the ice melt during the summer of 2021’s “heat dome”, on the Wapta icefield — the source of Alberta’s Bow River and glacier — was three times the normal rate over the dozen years prior to the event. Glaciers in the Canadian Rockies are also melting at an unprecedented pace. Last summer’s record-breaking heat caused the iconic Peyto glacier in Banff National Park, to melt at the highest levels ever recorded. Since the early 1900’s, Peyto has receded 3.5 kilometers; it is expected to be gone within a decade. To visualize what that means, picture standing on the glacier today. Sixty years ago, you would have been 200 meters higher.

Making the phenomenon worse, soot from hundreds of wildfires is landing on the glaciers, darkening them up and accelerating the rate of ice melt.

Peyto is part of the headwaters to the North Saskatchewan River, a life source for many across the prairie provinces. A source told Global News “it’s not impossible to imagine if we’re losing ice at the rate of the Peyto glacier this year, that our rivers would run dry in August or September. This is like grievously serious for life on the prairies. The world as we know it is being transformed as we watch.”

Prof. Kavanaugh says glaciers keep our rivers flowing when other water sources, like snow melt, dry up. He predicts the next few decades will be marked by high flows in our glacial rivers, but after that, “it will start to fall off a cliff. How much water is flowing through the river as a function of that time of year is going to start changing remarkably.”

Personally I see the latter as “nature’s cover-up”. People can easily be fooled into thinking that streams and rivers are full because there is plenty of snowpack, when in fact it’s because glaciers are melting. The cover-up may last several years, it takes a long time for glaciers to completely melt, but once they do, all that will be left to re-charge rivers, lakes and reservoirs, is the annual snowpack, that will become smaller and smaller as the Earth warms. Glacial melt is happening on a global scale, clarifying the enormity of the problem.

Research published in 2020 found that [m]eltwater from shrinking glaciers is creating vast lakes that could eventually pose an enormous flooding threat…

Glacial lakes form when meltwater from glaciers is prevented from draining by the ice itself. They form on top, in front, beside or even underneath a glacier.

They are growing at a rapid pace everywhere glaciers are found. Shugar and his colleagues estimate that the amount of water those lakes hold has increased by almost 50 per cent since 1990.

The total volume is calculated to be an almost-unimaginable 158 cubic kilometres of water. That’s a cube of icy cold water almost 5.5 kilometres long, wide and high.

Conclusion

Like all countries and regions, British Columbia is subject to the whims of changing weather, climate and global warming. Mother Nature cares nothing about who you are, or where you live. If all the elements of a perfect storm are present, natural disasters akin to what we have discussed in this article — extreme heat, wildfires, landslides and glacier-melt flooding, are likely to occur, with alarming frequency.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. Policymakers are wasting their time trying to stop global warming. The Earth will continue to warm until it starts to cool, following natural cycles that have continued for thousands of years. I accept that human-caused warming is accelerating what is already happening naturally.

The better course of action is to prepare for warmer temperatures, by planting drought-resistant crops; relocating low-elevation housing and public buildings that are in danger of being inundated by rising sea and river water; moving low-lying public infrastructure like sewage treatment plants and aquifers to higher ground; and carrying out storm mitigation measures, such as re-building older dikes and levies, and hardening highway bridges and overpasses to make them more resistant to extreme weather (100-year storms are now happening every 50 or 25 years).

Better forestry practices are also a crucial part of global warming mitigation, for lack of a better term. Thinning is the process of removing trees in a forest stand to reduce tree density and competition. It encourages the growth of fewer and stronger trees, while helping to reduce fuel buildup.

Prescribed burns are another useful strategy to rid an area of excess fuel that can keep a forest fire burning out of control for weeks. According to the province, key objectives include creating and maintaining strategic fuel breaks, reducing understory fuels, and improving wildlife habitat to achieve reforestation objectives.

The province adds that naturally occurring fires (and prescribed burns) help to keep insects and disease under control by killing the pathogens infecting a timber stand. It notes this is critical, given that in recent years more than five times as much timber in BC has been lost to insects and disease than wildfire.

For example where I live in north-central BC, spruce beetles have been chewing their way through thousands of hectares of forest, particularly in the Omineca region. In response to a public complaint, the Forest Practices Board found that, while the forest industry is making progress in recovering beetle-damaged timber, it called on the forest ministry to improve monitoring of industry’s response and report to the public about how the outbreak is being managed (Prince George Citizen). The article says the complainants are concerned that the licensees (Canfor and BC Timber Sales) are favoring lightly attacked and healthy forests, rather than harvesting the most severely infested trees.

A 2020 study by the Insurance Bureau of Canada, cited by Andrew Gage, staff lawyer at West Coast Environmental Law, calculates that local governments nation-wide need to spend $5.3 billion a year to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

The province points to scientific studies which concluded the extreme weather events of 2021, such as the atmospheric river and the heat dome, were made much more likely by global warming, and that such events will become more frequent as the climate continues to change.

Municipal elections are coming up this fall. What is your town or city doing to mitigate global warming?

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.