As infrastructure needs multiply, copper supply can’t keep up

2022.07.16

Copper is one of our most important metals with more than 20 million tonnes being consumed each year across a variety of industries, including building construction (wiring & piping,) power generation/ transmission, and electronic product manufacturing.

In recent years, the global transition towards clean energy has stretched the need for the tawny-colored metal even further. More copper will be required to feed our renewable energy infrastructure, such as photovoltaic cells used for solar power and wind turbines.

The metal is also a key component in transportation, and with increasing emphasis on electrification, demand is only going to increase, as EVs use about four times as much copper as regular internal combustion engine vehicles.

A major rise in copper demand from new “blacktop” infrastructure (think roads, bridges, airports, etc.), combined with high demand for copper from large-scale efforts on behalf of governments to decarbonize and electrify, is not being met with an adequate supply of the industrial metal. Trillions worth of new projects are thus in danger of falling by the wayside unless much more copper is discovered — more than is currently possible, in my opinion.

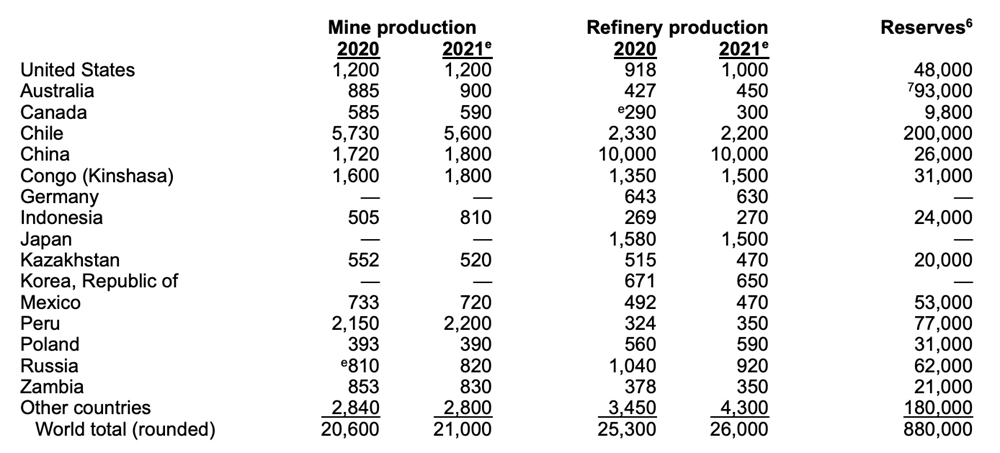

My position is supported by a recent report from S&P Global, which predicts the world’s appetite for copper will reach 53 million tonnes, on an annual basis, by mid-century. This is more than double current global mine production of 21Mt, according to the US Geological Survey.

How are we going to find the copper?

According to S&P Global’s report, via Reuters, Efforts to reach carbon neutrality by 2050 are likely to remain out of reach as copper supply fails to match demand amid the growing use of solar panels, electric vehicles, and other renewable technologies, data from S&P Global showed on Thursday.

As for where this new copper supply would come from, it won’t be from domestic sources. S&P Global forecasts that US copper imports are likely to grow from about 44% of the nation’s consumption this year to as much as 67% by 2035. It’s difficult to develop a copper mine (or any mine) in the US, due to organized opposition, over-regulation and length of permitting times, up to 20 years in some cases.

The Biden administration has made a number of anti-mining decisions, with the latest being the imposition of new pollution restrictions on the massive Pebble project in Alaska. Under the proposed requirements, the EPA would ban mine developer Northern Dynasty from disposing waste near the site due to potential harm to the area’s salmon fishery, effectively thwarting the long-stalled project.

President Biden himself took steps to block Antofagasta’s Twin Metals copper and nickel project in Minnesota, with the US Forest Service last fall proposing a 20-year ban on mining in the Boundary Waters region.

Meanwhile, four American environmental groups are reportedly zeroing in on two mines in British Columbia — the existing Copper Mountain Mine in southern BC, and the proposed KSM copper-gold project in the northwestern corner of the province — as examples of mines that are at risk of tailings dam failures.

In a press release quoted by Business in Vancouver, the groups say a proposed heightening of the tailings impoundment at Copper Mountain, located just 25 miles from the Washington border on the Similkameen River, threatens the Columbia River watershed.

As for the KSM mine proposal, the environmentalists say the mine located close to the Alaska border, would endanger US rivers and fish.

Back to my original point about the 53 million tonnes of copper demanded by mid-century. Countries are “pushing the boat out” on several large-scale, multi-year infrastructure projects, both traditional “blacktop” infrastructure and so-called “green” infrastructure, like electric vehicle/ battery plants and renewable energy projects. China gets the fact that to do this it will need more minerals. Beijing and its state-owned enterprises have been taking control of overseas mining projects or purchasing stakes in foreign mines, for the past 20 years.

The United States (and Canada) appears blind to the need to mine locally, with the Democratic administration unwilling to go to bat for the mining industry against environmentalists, a significant part of their voting base.

First the demand side of this quagmire, next the supply part of it.

Infrastructure push

Many countries need to reduce their so-called “infrastructure deficits”. Basic infrastructure such as roads, bridges, water & sewer systems, has been poorly maintained, and requires hefty investments, measured in trillions of dollars, to repair or replace.

China, the world’s biggest commodities consumer, has committed to spending at least US$2.3 trillion this year on major infrastructure projects. They are part of Beijing’s most recent Five-Year Plan that calls for developing “core technologies” including high-speed rail, power infrastructure and new energy. Translation: more money will be aside in years two to five. Note that China’s current infrastructure spending commitment for 2022 alone, is nearly double the United States’ which last November passed a US$1.2 trillion infrastructure package (more on that below).

An important part of China’s planned economy, infrastructure spending is frequently turned to when Beijing needs to shore up lagging economic growth, like currently. However, previous large infrastructure projects incurred a lot of debt, so restrictions were imposed on lending and spending by local governments, which in China are responsible for infrastructure build-outs. The result is a more targeted, fiscally sustainable approach to infrastructure spending.

According to recent media reports, China is moving forward by six months the sale of local government bonds. Beijing is mulling whether to allow municipalities to sell USD$220 billion of the special bonds. If permitted, it would be the first time that local governments sold bonds before Jan. 1, when the new budget year begins.

Funds from the sale of government debt, similar to the issuance of US Treasuries, would be used mostly to pay for infrastructure spending, which is being presented as a way to boost China’s beleaguered economy, with a goal of 5.5% GDP growth, as it claws its way back from a severe covid-19 lockdown.

According to China Briefing, key tasks include:

- Building high-speed and efficient information infrastructure to enhance data perception, transmission, storage, and computing capabilities.

- Large-scale deployment of 5G networks, increasing 5G uptake to 56 percent, and laying the technological groundwork for the development of 6G.

- Promoting the upgrade of gigabit fiber-optic networks.

- Promoting the commercial deployment of Internet Protocol Version 6 (IPv6).

- Building a national integrated big data center system and several national hub nodes and big data center clusters, including E-level and 10E-level supercomputing centers.

- Comprehensive development of the Internet of Things (IoT) and building IoT access capability that supports the integration of fixed-mobile and broadband.

- Building a space-based infrastructure system with global coverage to improve communication, navigation, and remote sensing.

As for traditional, materials-intensive infrastructure, the South China Morning Post published a list of six of the more exciting, and controversial projects — part of the 102 mega-projects that were included in Beijing’s 2021-25 development plan. They include:

1. Sichuan-Tibet railway

The Sichuan-Tibet railway is the second rail link between Tibet and hinterland provinces after a connection with Qinghai was launched in 2006.

2. South-North Water Transfer Project

China’s grand plan to divert dozens of billion cubic metres of water annually from the Yangtze River in the south to northern regions through three canals has been talked about since the early 1950s.

3. Yantai-Dalian Undersea Tunnel

The proposed tunnel between the eastern city of Yantai and Dalian to the north spans about 90km under the Bohai Sea and is more than twice the length of the Channel Tunnel between England and France.

4. Yarlung Zangbo River Dam

Building a hydropower dam on the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River, which is known in India as Brahmaputra River, was mentioned by Yan Zhiyong, chairman of the state-owned Power Construction Corporation of China, in November 2020.

5. Taiwan Strait Tunnel Project

The tunnel was proposed as part of the Beijing-Taipei Expressway, which, if completed, would connect the mainland with Taiwan. It has subsequently been included in China’s railway development plan.

6. Hongqi River Project

The Hongqi River Project, or Red Flag River Project, was proposed by social activist Gao Gan in 2017, with the aim of diverting water from Tibet to the dry lands of Xinjiang. Though it has no government support, it created a sensation on social media when it was put forward.

Bloomberg points to the capital, Beijing, as an example of how the construction drive is taking place; 300 major projects requiring 280 billion yuan in investment this year includes a panda breeding center, a Legoland theme park, and an electric vehicle factory operated by tech company Xiaomi Corp.

Also planned for Beijing, is a 2.2 billion-yuan expansion of a science and technology park to house a new generation of tech startups — a project that exemplifies Beijing’s support for the manufacturing and service industries, including factories, industrial parks, technology incubators, and even theme parks. “Now that China has basic modern infrastructure it makes sense to focus investment on manufacturing,” Bloomberg quotes Nancy Qian, professor at Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University.

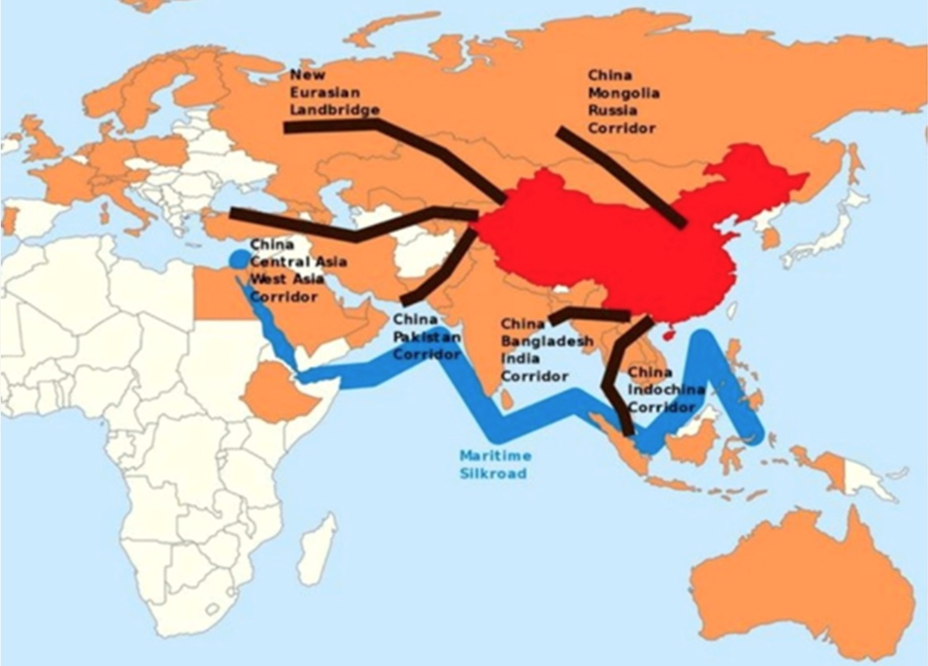

All of the above is on top of China’s $900 billion “Belt and Road Initiative”, designed to open channels between China and its neighbors, mostly through infrastructure investments. Dozens of countries have signed up to it, including Russia.

There is also the Made in China 2025 initiative, which seeks to end Chinese reliance on foreign technology by investing in a number of key sectors, including IT and robotics.

Research commissioned by the International Copper Association, quoted by Mining Technology, found that Belt and Road projects in over 60 Eurasian countries will push the demand for copper to 6.5 million tonnes by 2027.

That much copper equates to nearly a third of the 21Mt of copper produced in 2021 — new copper supply that would need to be either mined from existing operations or discovered.

The G7 just unveiled $600 billion to counter China’s Belt and Road.

Last month, US President Biden and other G7 leaders from Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan and the European Union, announced at a summit in Germany the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII). A White House press release said the agreement “will deliver game-changing projects to close the infrastructure gap in developing countries, strengthen the global economy and supply chains, and advance U.S. national security.”

The United States has committed $200 billion in grants, federal funds and private investment over five years, with Europe pledging $316 billion and Japan promising $65 billion.

Among the investments mentioned at the partnership’s launch on June 26, via NPR, to be paid for through a combination of public and private money, are:

- $2 billion for a solar project in Angola, including solar mini-grids, home power kits and solar to power telecommunications.

- $600 million for a U.S. company to build a submarine telecommunications cable that will connect Singapore to France through Egypt and the Horn of Africa, delivering high speed internet.

- $3.3 million in technical assistance from the U.S. to the Institut Pasteur de Dakar for development of an industrial-scale, multi-vaccine manufacturing facility in Senegal that could produce COVID-19 vaccines and others,in partnership with other G7 nations and the EU.

The US is also pursuing its own $1.2 trillion infrastructure package, to be spent on roads, bridges, power & water systems, transit, rail, electric vehicles, and upgrades to broadband, airports, ports and waterways, among many other items.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act is the largest expenditure on US infrastructure since the Federal Highways Act of 1956. Rolled out over 10 years, it includes $550B in new spending. According to S&P Global, Among the metals-intensive funding in the legislation is $110 billion for roads, bridges, and major projects, $66 billion for passenger and freight rail, $39 billion for public transit, and $7.5 billion for electric vehicles.

Again I have to ask, where are we gonna find the copper?

I’d like to think that the proponents of a $4 billion battery plant in Kansas, being proposed by Japan’s Panasonic which supplies EV batteries to Tesla, have thought about their future materials supply chain. Along with copper, Panasonic will also need to source battery metals, including lithium, sulfide nickel and graphite, all of which are in short supply or will be soon, in the face of booming demand.

The facility is expected to boost Panasonic’s energy production capacity from its current 50 gigawatt-hours per year to between 150 and 200 GWh. Surely a quadrupling of capacity calls for a major hike in the amount of battery raw materials required, along with the all the copper wiring that will need to go into each new vehicle.

Auto-makers and battery manufacturers can build as many plants as they like, to serve the growing electric-vehicle industry, if they don’t have enough copper supply, they are dead in the water.

Supply shortfall

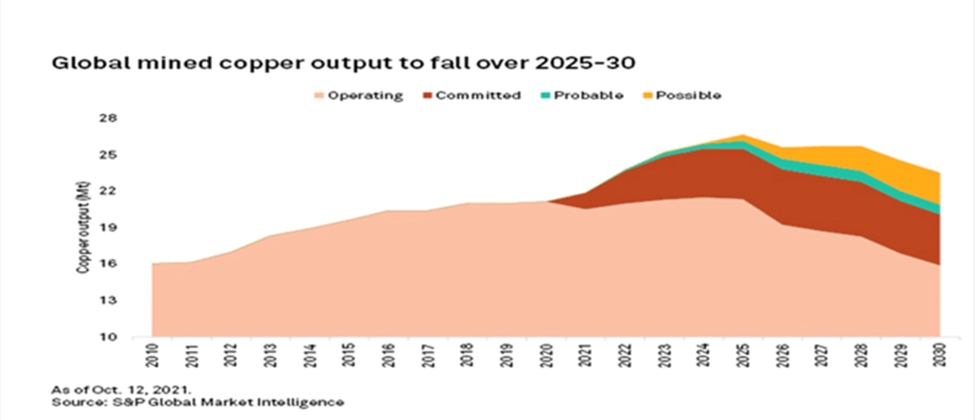

S&P Global Market Intelligence predicts that due to a shortage of projects, copper supply will lag demand starting as early as 2025, with global mine production dropping from last year’s 21.5Mt to roughly 15.9Mt in 2030.

Diminishing supply from currently operating mines, combined with the projected increase in demand for copper concentrate over 2021-2030, would result in a 3.85Mt production shortfall in 2025, S&P Global estimates.

A similar timeline was given by Bank of America in a recent report, which predicts the copper market to flip into a deficit as early as 2025 following the completion of the current wave of project buildouts.

“While visibility over the near-term project pipeline is good, activity increases come with a wrinkle,” the bank’s analysts say. “Indeed, many of the projects currently developed have been in the making for almost three decades, and with exploration activity relatively limited in recent years, supply increases may fade from 2025.”

BloombergNEF estimates that in 20 years, the world’s copper miners must double the amount of global production — from the current 20 million tonnes annually to 40 million tonnes — just to match the demand for a 30% penetration rate of electric vehicles.

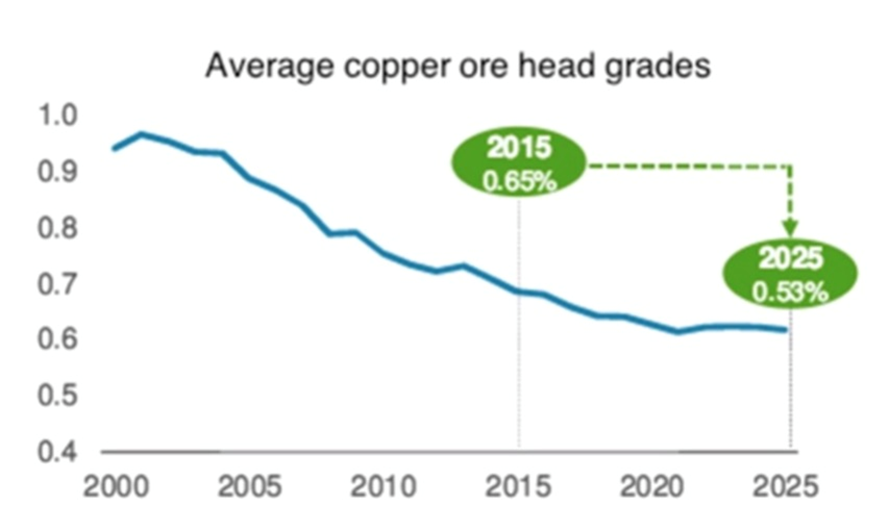

This is a tough ask considering some of the world’s largest mines are seeing depleted copper reserves and lower ore grades, so it would be difficult for global production to even maintain a 20-million-tonne-per-year pace.

CRU estimates that without new capital investments, global copper mined production will drop below 12 million tonnes in 2034, leading to a supply shortfall of more than 15 million tonnes.

According to CRU, there are over 200 copper mines that are expected to run out of ore before 2035, with not enough new mines in the pipeline to take their place.

Reserves at copper mines are dwindling worldwide, and so are the grades. Copper grades have declined about 25% in Chile over the last decade, bringing less ore to market.

Making matters worse, after more than a decade of drought, freshwater supplies are becoming a big problem in Chile. Copper mines there happen to require lots of water to process sulfide ores, and the lower the grade, the more water must be used.

Since major copper miners are increasingly turning to low-grade sulfide deposits to beef up their production, their water consumption is expected to jump up to 20.9 cubic meters per second (about half an average household pool). Water scarcity in effect hinders their ability to produce.

Conclusion

The copper market is tight based on a combination of factors including lower ore grades, droughts/ lack of fresh water, resource nationalism in top producers Chile and Peru, and a dearth of new discoveries in recent years. To avoid a copper shortage as early as 2025, billions will need to be spent on discovering new copper deposits.

AOTH research shows that new supply is concentrated in just five mines — Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC.

At Cobre Panana, nearly half of the 300,000 tonnes per year (tpy) production goes to Korea, under a 15-year offtake agreement.

The Kamoa-Kakula copper project is a joint venture between Ivanhoe Mines (39.6%), Zijin Mining Group (39.6%), Crystal River Global Limited (0.8%) and the DRC government. Last year Ivanhoe signed two offtake deals, one with a subsidiary of its partner firm, China’s Zijin Mining; the other with Chinese commodities trader CITIC Metal, to sell each 50% of the copper production from Kakula — the first of two mines involved in the joint venture. In other words, 100% of Kamoa-Kakula’s Phase 1 production goes to China.

That leaves three mines in Chile — Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca’s “QB2” expansion.

Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 project is expected to produce 316,000 tpy of copper equivalent for the first five years of its 28-year mine life. In 2019 the Canadian company closed a $1.2 billion transaction whereby Tokyo-based Sumitomo Metal Mining and Sumitomo Corp will, through an $800 million and a $400 million contribution, acquire a 30% interest in project owner Compañia Minera Teck Quebrada Blanca S.A. (“QBSA”).

Summing up, our analysis showed that in two of the five mines where new copper supply is concentrated, there are offtake agreements in place with non-Western buyers. In the case of Kamoa-Kaukula, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project. Nearly half of Cobre Panama’s annual production goes to a Korean smelter under a 2017 offtake agreement. A large Japanese company owns 30% of QB2.

What this means is that a significant portion of new mine supply is tied up in offtake agreements with China, Japan or Korea, meaning it cannot be purchased by Western countries (Europe, the US, Canada) on the open market. Moreover, this 2 million tonnes, approximately, is not even close to how much copper will actually be required — 53 million tonnes a year, by 2050, if S&P Global’s forecast is accurate, necessitating a more than doubling of current mine supply of 21Mt.

The amount of new infrastructure being announced by the United States and China, mostly, is mind-boggling, but how much of it will actually be built if not enough copper (and other minerals) can be sourced?

A copper crunch is coming within the next three years but the drop in the copper price due to Fed expectations of interest rate hikes and less metals demanded in the event of a global recession, is diverting attention from this fact.

The economic situation in China, the world’s largest copper consumer, is improving following the lifting of covid-19 lockdowns that hurt manufacturing activity. According to Reuters, China’s copper imports rose 15% from a month ago, after demand picked up. The country’s PMI hit 50.2 in June compared to 49.6 in May, which is the first time it went above 50 since February. (any number above 50 is considered growth, below 50 is a contraction).

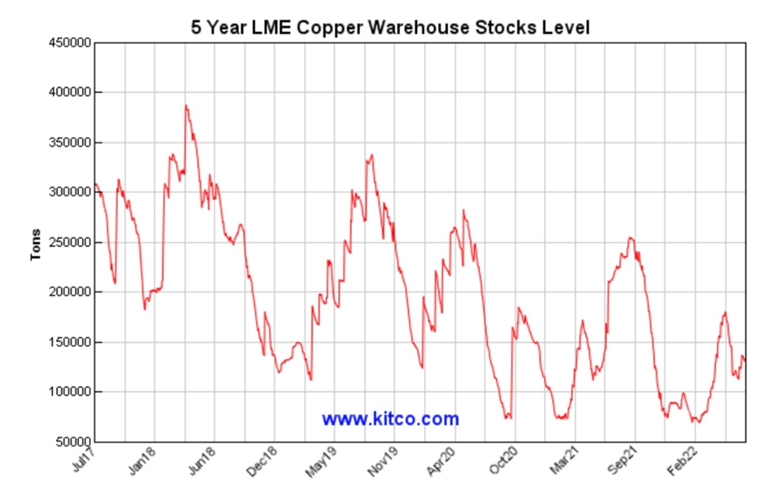

The publication’s metals columnist, Andy Home, notes that “the scale of the disconnect between price and stocks is striking.” Indeed, despite a falling copper price, inventories at metal exchange warehouses have stayed low. That should raise prices but according to Home, “Right now, however, macro is trumping micro as Western recession fears pummel the industrial metals complex.”

Combined inventory across all three major copper venues — the LME, CME and the Shanghai Futures Exchange — totaled 261,000 tonnes at the end of June, 71,000 tonnes higher than the start of January but down by 150,000 compared to June, 2021.

Home notes in his analysis that LME warehouses held just 696,109 tonnes of registered metal at the end of June, the lowest amount this century. Off-market metal, so-called “shadow stocks”, rebuilt modestly in April but only increased year to date by a negligible 4,600 tonnes.

Also, weaker demand in China hasn’t impacted ShFE inventories, which remain at 69,000 tonnes, down from 129,500t a year ago, he added.

Macro may be trumping micro but it’s only a matter of time before the supply side of the copper equation is re-calibrated into the price. The disconnect between the copper price and dwindling exchange inventories can only hold out for so long. And as the demand for copper keeps soaring, fueled by trillions in infrastructure spending, without nearly enough mine supply to match it, the fundamentals to me look incredibly bullish.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe to my free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.